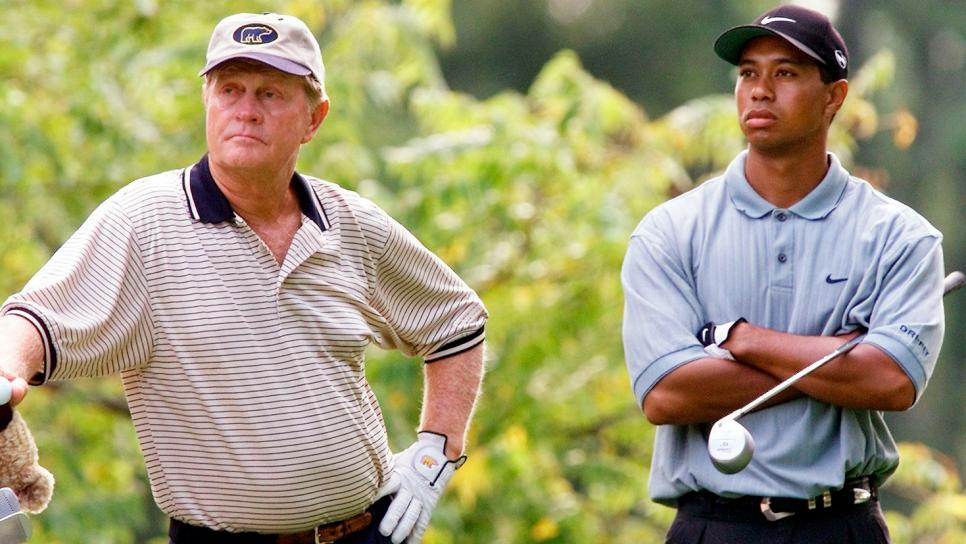

In 110-degree heat, surrounded by a rocky moonscape in the California desert, the contrast between them never looked so stark. Not only are their ages of 62 and 26 numerical flips, but a 6-iron for one was a 9-iron for the other. They were thick and thin, light and dark, old and young, open and closed, heartland and Pacific Rim, Teutonic and Cablinasian, laboring and lithe. Partners at the made-for-TV "Battle at Bighorn," Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods looked more like the shaky premise for a buddy sitcom than the two most compared athletes from the past and present in the history of sports.

But in the still, silent moments on each tee, the differences fell away. As one addressed the ball, the other turned his legendary focus to every movement and mannerism, hungry to better understand what was special in themselves. Two years before, at the 2000 PGA Championship, in the only time they were paired in an official event, it had taken another prolonged look at Woods for Nicklaus to definitively know that his time had come to stop competing in majors. Through their elevated senses, Woods has connected with just what it took to win 20 major championships, while Nicklaus understands why Woods has the capacity to win even more.

"It's kind of amazing how two different people from two different eras who don't have much contact can feel close," says Woods, "but we do."

Not so amazing, actually. Piecing together their shared attributes as golfers would create two detailed mosaics with but a few unfilled spaces. Nicklaus has said there's not a "nickel's worth of difference" in their iron play, and you can call their levels of intensity, concentration, intimidation, domination, toughness, resilience, intelligence and tenaciousness a push as well. Both are equally calculating, methodical and consistent. Both built their games around power, stressing the fundamentals. They hit the finest long irons ever seen. From the rough? Wondrous. Extra good on par putts. The more pressure, the more fun. They each love to prepare, excel at peaking and have built their lives around the majors. Both are perfectionists and supreme egoists, loyal to friends and encouraging to struggling pros. They possess selective memories, were brought up by ultra-supportive parents, believe second place stinks, never quit and have been merciless closers and graceful losers.

Somehow, the cruel game would never turn on them as it did others. "It's amazing that as many times as he came to the last hole with the tournament on the line, Jack never had a Doug Sanders moment," says Johnny Miller.

"Jack, and I'm sure Tiger, just believe they're miracle workers," says Tom Weiskopf.

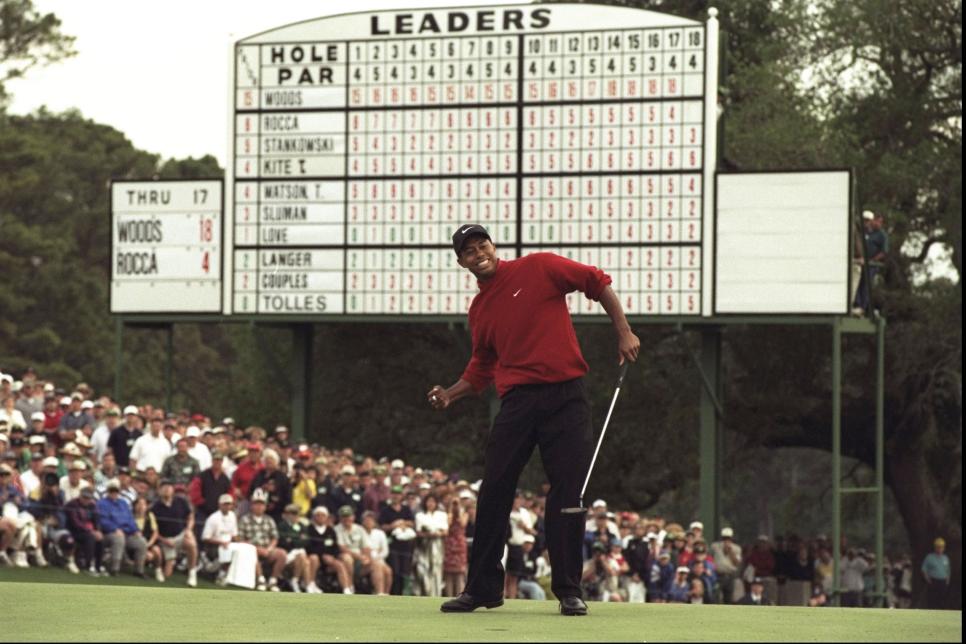

Out of respect to the other, they both resist comparisons, Nicklaus because he doesn't want to appear stuck in the past, Woods because he knows conquering the future means staying in the present. But now that Woods has completed six full pro seasons, there never has been a better time to compare. Nicklaus' first six years had been the greatest start on the PGA Tour, in which he won seven majors to add to two U.S. Amateurs. In the same period, Woods has been even better, with eight pro majors to go with three Amateurs.

As Woods is embarking on what writer Bill Fields calls "the long middle," the seventh season is when Nicklaus entered the first fallow period of his career, going three years between major victories at the 1967 U.S. Open and the 1970 British. It's a chance for Woods, whose only full year as a pro without a major came in 1998, to make a major move.

He's primed. Since Woods broke away from the pack in late 1999, no No. 1 in the history of golf has been this far ahead of the next-best player.

"I would never deny that Jack Nicklaus is the greatest player who ever lived," says Gary Player, "but Jack was never this dominant."

Adds Miller: "You look at Bobby Jones, and what he did was amazing. Then you look at Nicklaus, and that was amazing, too. But when you look at Tiger, there's nothing like it in history."

'It's kind of amazing how two different people from two different eras who don't have much contact can feel close, but we do.'—Tiger Woods

The highest praise of all comes Tiger's way, from Jack. "I would be very surprised if he doesn't break my records," Nicklaus has said. "Very surprised. At the rate he's going, it's not such an awfully long haul."

Even if he doesn't keep up his pace, Woods has another built-in advantage: He is chasing. "Tiger has someone to compare his greatness," says Hubert Green. "Jack just went out and played. Every time Jack won, it was his record. If he had had what Tiger has, he might have been better."

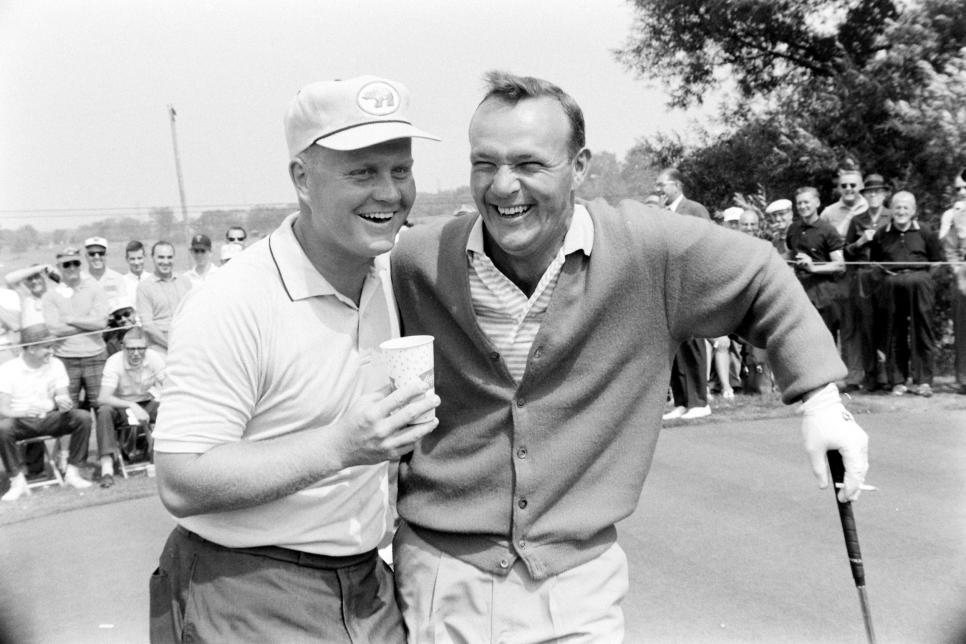

Nicklaus' advantage is longevity achieved, because tomorrow is guaranteed to no one. In his record span between winning his first and last professional majors (the 1962 U.S. Open and the '86 Masters), Nicklaus excelled amid three waves of greats: the first headed by Palmer, Player and Casper, the next including Trevino, Floyd and Miller, and the last led by Watson and Ballesteros. For Woods to pass Nicklaus, his winning span will almost certainly have to last more than a decade.

"Of course, he has all the ingredients to do it, every single one," Player says of Woods. "But he's still got to do it. So many things can go wrong. Great players—Palmer, Watson, Seve—they all stopped in their early 30s.

Everything looked great, yet their time for winning majors was small."

Today's tour players, who see the attention and scrutiny Woods undergoes, agree it's no gimme. Wonders Olin Browne: "How long can he take it without his brain being fried?"

Nicklaus knows best how tough that battle is. "You only have so much juice," he once said. "You try to keep what you've got left so you can use it when it means the most."

ADVANTAGE, NICKLAUS

Icon Sportswire

With Woods' talent a given, the heart of the matter is longevity. A close study of Nicklaus shows that he was preternaturally equipped for the long haul. And in some important ways, more so than Woods.

Athleticism

Nicklaus' early image as Ohio Fats obscured the fact that he was an exceptional all-around athlete. Following the lead of his father, Charlie—who played baseball, football and basketball at Ohio State and was later the Columbus public courts tennis champion—Nicklaus in eighth grade was a switch-hitting catcher on the baseball team, a quarterback on the football team, a sprinter on the track team (11 flat in the 100-yard dash) and a forward in basketball, going on to become honorable mention all-state his senior year.

In all sports, Nicklaus exhibited a knack for the winning moment. "You mean that thing my dad's got where he makes a 30-footer to win three presses?" asks son Gary. The point is, much like Sam Snead, Nicklaus' longevity was built on an exceptionally tall mountain of physical talent.

Nicklaus at his physical peak in the early '60s was a marvel to his peers. "As thick as Jack's hips were, he moved them faster than anyone else on the tour," says former player Phil Rodgers. "It was startling speed, this truly awesome athletic move, like Tiger's but with so much more mass. It gave me the same sensation I got watching Jim Brown run."

Nicklaus governed his power with exceptional feel; he once made 26 straight free throws in high school competition. "What separates Jack is the sensitivity with his hands," says teacher Jim Flick. "It is beyond anyone else I have ever seen."

Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus smiling together in 1963.

Francis Miller

Though he never focused on becoming exceptionally fit aerobically, Nicklaus had an innate stamina that allowed him to practice for long periods with full concentration. "My great gift has been energy," says Player, "but Jack had as much as I had."

"Jack was like a Clydesdale," says Rodgers. "He would just work all day and just go and go and go. I get the sense that Tiger is more of a thoroughbred, maybe more brilliant, but prone to burn out if not handled with care."

Although there is no denying the classic intersection of speed, power and stability in Woods' swing, the only time he played an organized sport other than golf was running cross-country in junior high school.

"I would have liked to have played other sports, especially baseball, but I don't know how good an all-around athlete I would have been," says Woods. "Probably around JV [junior-varsity] level. I certainly wouldn't have been any Jim Brown, that's for sure."

Normalcy

Nicklaus grew up in a tightly knit, upper-middle-class family in Columbus. His father was a successful pharmacist who was his son's biggest fan and best friend. Jack took up golf at age 10, but until he won the Ohio Open in 1956, his golf exploits were limited to mostly local junior events. Later, when he became a two-time U.S. Amateur champion, his intention to eschew professional golf and make a living selling insurance sparked little public debate. "I didn't even decide that golf was a significant part of my life until I was 19," he says. "By that time, Tiger was public property."

Since moving to Florida in 1965, Nicklaus has lived in the same one-story home in North Palm Beach, and all five of his grown children and 15 grandchildren live within 10 minutes. Last year when he followed son Gary at the Memorial Tournament, Nicklaus moved easily among people from his hometown. "As abnormal as Jack's success has been, it has never overpowered all the very normal things about him," says Ken Bowden, Nicklaus' co-author on 10 books. "He has never lost who he is."

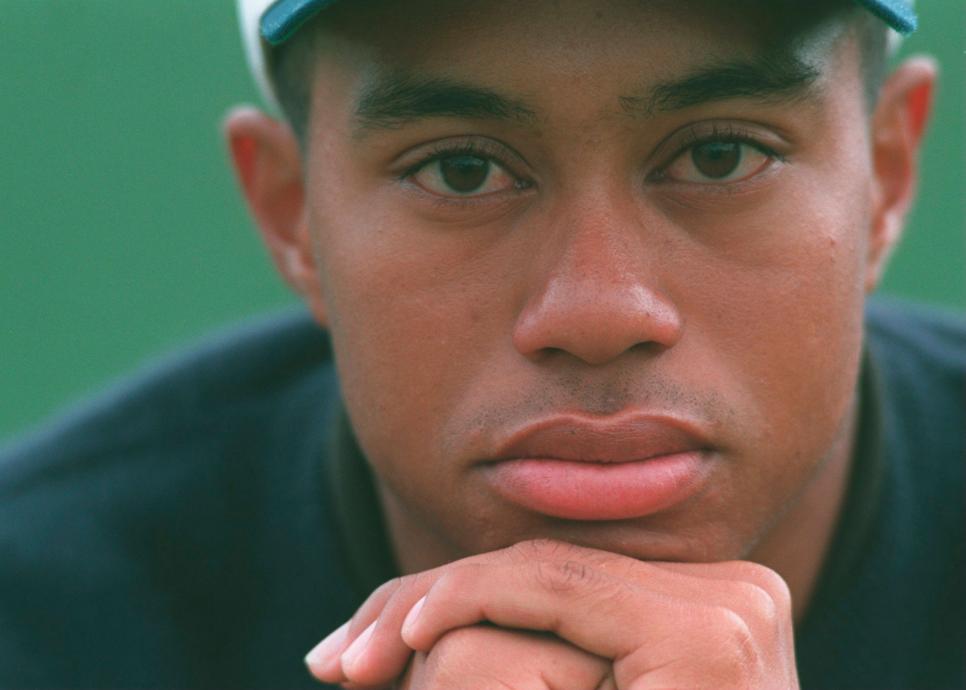

Woods also had a stable upbringing and close relationship with his parents, but from the age of 8 he has led a highly structured life geared to success in competitive golf. Woods has made an uneasy peace with being a public figure; almost in surrender, his favorite pastimes have become solitude-seeking escapes like scuba diving and fishing. "No autographs underwater," he says, marveling at Nicklaus' run at having it all. "What's so remarkable about Jack is the balance he retained in his life while staying the best for so long," Tiger said in 2000.

"I can already see how difficult that's going to be for me."

'Playing badly well'

Over three decades, Nicklaus garnered the majority of his victories while compensating in various ways for a flawed swing. He called it "playing badly well."

Nicklaus often has said he probably swung the club better as an amateur than as a professional. The 1960 U.S. Open at Cherry Hills and the 1960 World Amateur at Merion are two events in particular where he achieved sensations of effortless control and power that he never was able to recapture.

As a pro, Nicklaus found that the constant travel and changing conditions of tour life made it harder to maintain a groove. Thereafter, he mostly relied on well-conceived band-aids and management skills to bring his game up for the biggest moments.

R&A Championship/Getty Images

Nicklaus' knack for self-correction had its source in teacher Jack Grout, who, after imparting the fundamentals, liked to see his students employ trial and error to understand how and why their swings worked. Nicklaus was further encouraged in this approach by Bobby Jones, who had not considered himself a good player until he could diagnose himself. Nicklaus' emotional control also was vital to accepting less than his best.

"When he was hitting it bad, Jack would find a way to live with it," says Weiskopf. "Considering his talent and perfectionism, that took an incredible amount of patience. He just refused to get disgusted, and beat us with will."

All in all, says Player, "Jack's greatest strength was playing junk and scoring 68."

Woods probably plays less "junk," but he doesn't live with it quite as well. He seems by perfectionist temperament inclined to fight tendencies he doesn't like rather than working around them, as his relative lack of second-place finishes indicate. His most recent decision to curtail his work with Butch Harmon suggests he wants to be more self-reliant, in the Jones tradition. Without seeking help at this year's PGA, an out-of-sync Woods finished second in a major for the first time.

Style of play

Nicklaus' tee-to-green style was designed to reduce, not induce, internal stress. In anticipation of the control Jack would need to temper his power, Grout trained him to groove a softer-landing slight fade that made Nicklaus the straightest big hitter ever seen. When he did stray, he tended to play conservative recoveries. But even from the fairway, Nicklaus rarely shot directly at the pin, in part because he was not a great wedge or bunker player.

"In Jack's mind, his perfect iron shot was 18 feet left of the pin," says Miller. "His thinking was, 'It takes all the danger out of play, and now I'm going to make the 18-footer.' "

At the 1967 U.S. Open at Baltusrol, Nicklaus hit 61 of 72 greens in regulation, believed to be a record for that championship. As late as 1980, at age 40, Nicklaus led the tour in greens in regulation and total driving.

"Jack seemed to go for broke only when he was behind at the end of a tournament, and it was so impressive," says Player. "We were probably lucky he didn't try to do it more often."

Woods plays a more psychologically wearing style. Because the modern golf ball is flying longer and straighter, he has more incentive to gamble off the tee and with his approaches, but misses leave him with more testing recoveries. Woods' three most recent major victories, however, were won in a more Nicklausian style. "Since 2000, I probably haven't improved that much physically," Woods says, "but my management is much better."

Putting

Nicklaus' approach to putting was the most vital way in which he saved his juice. Once on the green, he stressed correct speed on putts outside 15 feet to leave the shortest possible second putt. His goal of avoiding knee-knockers was helped by the slower green speeds of the '60s, '70s and even the '80s.

"I was a fine two-putter, but sometimes too defensive—too concerned about three-putting," he wrote in his autobiography, My Story.

Stephen Green-Armytage

Nicklaus didn't make every must-have six-footer, but never in 40 years of championship golf did he look less than poised over a big putt. "Jack was always a solid putter," says Davis Love III. "Then on the back nine on Sunday, he turned into the greatest putter ever."

Most observers believe Woods makes more long putts than Nicklaus, but he probably misses more short ones. His bolder style, combined with ever-quickening green speeds, forces him to face down more six-footers for par than Nicklaus, while his tendency to ram his short putts can produce lip-outs. Both Palmer and Watson used this style to great success until their early 30s, when with shocking swiftness they became poor short putters, their mental reserves used up.

Compartmentalization

Though Nicklaus was often second-guessed for having too many interests to focus on golf—whether it was family, course architecture, running his company or hunting and fishing—he has no doubt they kept him energized.

"They allowed me to create diversions in my life, to be able to get away from playing golf," he says. "When I went back to playing golf, I was able to concentrate and play harder, because I was able to focus when I wanted to focus."

This ability to hunker down has been severely tested. In the early '70s, Nicklaus, at considerable financial risk, embarked on the most ambitious project of his life, building Muirfield Village Golf Club. It's no coincidence, he believes, that "1972 to '75 was my best golf." After Nicklaus set up Golden Bear Enterprises with the goal of making enough money to ensure security for generations of Nicklauses, he was devastated in 1985 to discover he was facing the possible ruin of his empire because of the insolvency of two other golf course developments. One former executive at Golden Bear said the period was so stressful that Nicklaus "was having shortness of breath, basically anxiety attacks." Nicklaus had to negotiate with bankers in deals that cost him millions, but in the midst of that, he produced his greatest victory, the 1986 Masters. Did the financial pressures that Nicklaus felt in the latter half of his career force him to play harder and longer than he would have otherwise? "No," he says flatly. "I missed some three-foot putts in business. Heck, I missed quite a few three-foot putts on the golf course, too."

It's highly doubtful that the already ultra-wealthy Woods will ever feel similar pressures to keep playing. But without the Nicklaus trait of drawing extra energy from a loaded-up life, inevitable complications will come with time.

Rating the competition

Because Woods will be forced to beat more players capable of winning majors than Nicklaus did, longevity will be more difficult to achieve for him. "Especially in the '60s, you'd see a lot of majors where at the end there would be only five or six guys within 10 strokes," says Rodgers. "Maybe three or four guys would have a chance to win on the weekend. Today at a major, you see 20 guys finish within 10 strokes. One of the reasons Jack was able to finish second and third so often is he didn't have to contend with that kind of depth."

Much has been made over the assertion that Nicklaus faced a more accomplished and tougher group of players at the very top of the game than Tiger does. The trio that put together the most major victories against Nicklaus in his first six years—Arnold Palmer, Gary Player and Billy Casper—won six in that period. But Ernie Els, Mark O'Meara and Vijay Singh got the same number in the same time against Woods.

Meanwhile, the increased popularity of golf worldwide—directly attributable to Woods—is drawing better and better athletes to the game. As Woods has often said while watching youngsters at his clinics, "Out there, right now, are kids that are going to be better than me. They're coming fast."

Anger management

Partly because of natural makeup, and partly due to will, Nicklaus' temperament was built to last.

Nicklaus has what sport psychologists call a "low arousal" personality. When tournament pressure increased, it generally elevated his intensity to an ideal state rather than overload.

Of course, Nicklaus was the master of dealing with the great career shortener—frustration. It seems that once admonished by his father at age 11 for throwing a club, Nicklaus made the adjustment that most golfers don't learn until their 30s (and some never do).

"I never once saw Jack Nicklaus lose his poise on the golf course," says David Graham. "I can't say that about any other champion I ever played with."

Although Woods has the ability to remain serene in the most pressure-packed moments, he appears to burn much hotter. Woods usually is able to exemplify what Sam Snead called the ideal state for playing: "cool mad." But Woods has lost it—slamming clubs or unleashing profanity—on many occasions. "Inside of Tiger burns a volcano, and I've seen it erupt," says his father, Earl. "And it is not nice there."

Barbara Nicklaus

Nicklaus was only 20 when he married the former Barbara Bash on July 23, 1960. Because of his wife's blend of intelligence, organization, selflessness, friendliness and calm, for more than four decades Nicklaus benefited from the ultimate intangible.

"The Nicklaus house is always full of people—kids, grandkids, friends—and Barbara is like the CEO," says Nicklaus adviser Chris Roderick. "It could be chaos, but it's by far the most organized part of Jack's life. She's a stress reducer, and for a professional golfer, that's not a given."

Jack with his wife Barbara after his win in the 1970 Open Championship at the Old Course.

R&A Championships

Adds Nicklaus: "I never took golf home. The last thing I wanted to do was go home and discuss eight-footers with my wife, and the last thing she wanted was for me to come home and discuss eight-footers with her. It works both ways."

Woods has remained private about his relationships. At the moment, he seems content in bachelorhood, although he and girlfriend Elin Nordegren have been together for a year and a half. Nicklaus has said that if his career as a golfer had ever seriously threatened his marriage, he would have quit golf cold, but Woods' signals are that any life partner would have to be able to coexist with his pursuit of greatness.

Media relations

Considered "too darn sure of myself" in his early years on tour, Nicklaus came to enjoy what he considered his responsibility as the game's best player to be accessible and cooperative with the media. The expansiveness of his answers earned him the locker-room nickname "Carnac," after the all-knowing Johnny Carson character, but those who covered him appreciated his willingness to provide detailed insight into his life and golf.

Nicklaus proved his mettle at the 1963 U.S. Open, where as the defending champion he gave long interviews after shooting 76-77 to miss the cut, and most tellingly at the 1981 Open Championship, where he shot an opening-round 83 after learning that his son Steve had crashed his car on the Jack Nicklaus Freeway in Columbus. Nicklaus initially declined to be interviewed, but after a few minutes invited the media to his locker and spoke about his round and his emotions as a father. Other than the 1972 season, when he felt invaded by the intense scrutiny his pursuit of the Grand Slam drew, the older he got, the more Nicklaus seemed to enjoy the give and take with the media.

Precisely because of Woods' impact on the game's popularity, the media people who cover him are much larger in number and much hungrier for information. Because of Woods' sensitivity to criticism, it's not surprising that his group interviews are generally marked by the awkward rhythm of reporters straining to ask penetrating questions and Woods doggedly constructing sterile answers. The week before the Ryder Cup in September, Woods was being peppered about his attitude toward the event when he turned the tables on a questioner. "Let me ask you a question," he said. "Would you rip me?" But the more Woods withholds, the more the media grasps.

"I never had to deal with what Tiger's had to deal with," says Nicklaus. "It's the hardest thing he's going to have to deal with." Says Woods: "I'll handle the responsibility of doing it, but I don't have to like doing it."

ADVANTAGE, WOODS

Stephen Munday

Woods may or may not last as long at the top as Nicklaus. Then again, to surpass Nicklaus' record, he may not have to. What can be ascertained is that his tools are the most formidable ever. "He's more complete," admits Nicklaus. "Whatever I had, I think this young man has more of it."

The mental edge

Nicklaus' musings about how he thinks on the course have long been a model for sport psychologists, but Woods' ability to produce peak performance by "willing myself into the zone" is unprecedented. In his Thai background on his mother's side, Woods has been exposed to eastern philosophy in a way that no other all-time great player ever has. "He carries a real serenity," says Dr. Deborah Graham, "a very Zen-like approach that seems innate."

Earl Woods, an ex-Green Beret, used techniques derived from interrogation tactics to toughen his son. And at age 13, Tiger began mental training with Dr. Jay Brunza, a family friend and psychologist. "His creative imagination and his trust in himself are off the charts," says Brunza. "You're working with a Leonardo, and you let the eagle soar." Among the techniques Brunza used were subliminal tapes and hypnosis. "The first time Jay hypnotized Tiger, he had him stick his arm straight out and told him that it couldn't be moved," Earl says. "I tried, but I couldn't pull it down."

Woods says he no longer uses tapes or formal hypnosis. "But I think I used it enough then that it's inherent in what I do now," he says. "Everyone had always told me to visualize shots, but I could never see the ball. We worked on a way to look at the target and pull it back into my hands and body, and let my subconscious react. That's what works best for me."

Short game

Nicklaus concurs that Woods' biggest edge over him is in his phenomenal short game.

"You can talk about all the fancy Phil Mickelson flop shots," says Johnny Miller, "but Tiger has the best short game I have ever seen, especially under pressure."

"He's way ahead of everyone," agrees Rodgers, who helped Nicklaus improve his short game before the 1980 season, when Jack won his 18th and 19th majors.

Woods benefited from being slow to mature physically, in contrast to Nicklaus, who was 5-feet-10 and 165 pounds at age 13. To keep up with stronger junior golfers, Woods learned how the short game could be an equalizer.

"First of all, I always loved learning all the little shots, so practicing was fun," he says. "Second, I realized it's impossible to have too good a short game."

Nicklaus' short game cost him at least one major, the 1971 U.S. Open against Trevino. "I asked Jack recently what he would change if he could redo his career," says Flick. "He said he would have spent a little more time on his short game."

Work ethic

Although Nicklaus admits he could not sustain the intense practice regimen of his earliest days, Woods has never slacked off. His work ethic is such that he is in the pantheon of practicers. "You work hard on making your weaknesses your strengths," he says. "I've changed a lot of things to get to that point." Besides being structured and focused, Woods has the advantage of deeply enjoying the act of hitting shots. "Peace at last," he sometimes sighs when beginning a post-round practice session.

Nicklaus' first period of laziness snuck up on him after his victory at the 1967 U.S. Open, but it took his father's death in 1970 to make him realize it. "I had gotten very sloppy," he said in 2000. "I had wasted time."

Hand in hand with Woods' work ethic is a curiosity that differentiates him from Nicklaus. "Tiger is very, very willing to learn and doesn't buy into the idea that he knows everything," says Alastair Johnston of International Management Group. "Jack wasn't called Carnac for nothing."

Nicklaus isn't second-guessing his approach, however.

"Do I think I could have been better?" he says. "If I had worked at it as hard as some guys work at it today, yeah. But I probably would have had a much shorter career."

Body

Nicklaus may have been more accomplished at other sports, but Woods has the superior physical tools.

At 6-feet-2 and now 185 pounds of lean muscle, Woods has a more classic athletic build, ideally configured to make the huge shoulder turn and restricted hip turn that give the modern golf swing its combination of simplicity and power. And the speed at which he moves through the ball demonstrates he has the predominance of fast-twitch muscle fibers that are ideal for explosive movements like the golf swing.

Nicklaus might've been more accomplished at other sports, but Woods has superior physical tools.—Jaime Diaz

Nicklaus was formidable with his 29-inch thighs and his own fast-twitch speed through the ball. But at 5-11 with short limbs, he needed to make a more complicated move—a bigger hip turn and a lifting of the left heel—to achieve the leverage produced more easily by Woods.

Naturally small-boned, Woods was relatively frail at 155 pounds when he joined the tour in 1996. Aware that his fast clubhead speed put his joints at risk, and wanting to protect against future back injury by developing a swing based on the big muscles, Woods hit the weights hard in his first few years on tour. More recently, he has altered his physical regimen to push less weight with more golf-specific exercises.

He continues to work on his forearms to better "hold the hit" through impact, he runs to strengthen his lower body and improve endurance, and he does occasional sprints to build more explosive strength on the downswing. During a week of competition, Woods will lift two days and run three days. The former cross-country runner still keeps a brisk pace, running four miles in just over 30 minutes.

In Nicklaus' first eight years on tour, he was overweight, ranging between 205 and 215 pounds as a "compulsive eater." When Nicklaus noticed how tired he got playing 36 holes on the final day of the 1969 Ryder Cup, he went on a diet, losing 25 pounds and seven inches around his hips. Although the slimmer look improved his appearance, it cost him distance that he never regained. If Nicklaus had incorporated a strength-training program as he lost the weight, he might have increased rather than lost power.

The swing

The best players from each succeeding generation almost always have technically sounder swings than their predecessors. Improvements in equipment also lead to style changes. That said, Woods' swing in relation to his peers is biomechanically sounder than Nicklaus' was.

"They have different body types, so that accounts for a lot of the difference," says David Leadbetter. "Tiger could make a bigger coil with his left heel on the ground. Jack had massive legs, which allowed him to perhaps be more stable on the downswing. But in terms of pure overall technique, Tiger's method is slightly more efficient, repeatable, consistent and versatile."

Many students of the game consider Woods' swing—from poised address to beautifully balanced finish—to be the closest thing yet to perfection.

"Tiger has no idiosyncrasies," says Nick Faldo. "If you tried to do some caricature of his swing, exaggerate some mannerism, you really couldn't."

Woods' swing is the result of an obsessive attention since boyhood to incorporate the best traits of the best players. "It was never one person," says Woods. "I've tried to pick like 50 players and take the best out of them and make one super player."

Nicklaus' style was revolutionary and superior in key ways to the methods of his peers. With the fullest turn the men's game had ever seen, his uprightness allowed him to hit the ball high, to greatest effect with his long irons, and to play from rough with near impunity. But executing such a move required enormous strength and flexibility, for without a tremendous coiling to create sufficient depth, Nicklaus' club would approach the ball on such a steep angle that consistent solid contact became difficult. "Snead and Weiskopf both hit the ball better than Jack," says Player. Loss of physical strength was a primary reason Nicklaus was forced in 1980 to make the biggest swing overhaul of his career and flatten his plane.

When it comes to the golf swing, Woods is by nature more technically oriented, experimental and curious than Nicklaus. In 1997, Tiger took the risk of decreasing the hand action and increasing the body rotation in the swing he had used to win the Masters by 12 strokes. With his improved method, Woods has lost a bit of distance but gained control. The most persistent mistake he fights is rotating his lower body too quickly on the downswing, getting the club "stuck" behind him. Unlike at any time in his life, he is in a maintenance mode, a difficult time for someone seeking constant improvement.

Killer instinct

No one ever questioned Jack Nicklaus' killer instinct. Likewise, he was well aware of his power of intimidation. Other players thought they had to stretch beyond their abilities. "They really didn't," he says, "but they believed that."

As much as winning, Woods plays to crush his opponents' competitive will. Such was the effect of Woods' double-digit margins of victory at Augusta and Pebble Beach.

"He wants to stomp your heart out," says Hubert Green. "Jack just wanted to win. Tiger likes to rub it in."

Nicklaus didn't. After Trevino skipped the 1971 Masters, Nicklaus told him he wasn't doing his talent justice.

"What Jack said to me turned me around, and it didn't do him any good," says Trevino. "He didn't have to do it, but that's the kind of champion he is." And in contrast to the way Woods avoided playing with Mickelson at this year's World Cup, Nicklaus at the 1973 World Cup afforded Miller the biggest confidence injection of his career. "Because Jack let me see him close up and was so open talking about the game, he made himself human for me, to the point where I began to believe I could beat him," says Miller. "What's amazing is that he wanted me to feel that way."

Woods keeps his distance from those who dare to openly challenge him—Mickelson and Sergio Garcia in particular. "Just because I've become friends with more guys now doesn't mean I have a hard time trying to kick their butts," he says. "It actually makes having the killer instinct easier, because that's what professional athletes do, and it's not personal."

Heroics

It's true that Woods lives in an ESPN highlight world, but there is no doubt that in the biggest moments he raises himself like no golfer before him. Woods says such moments occur because of, not despite, the pressure. "Your senses are heightened when you're in a clutch situation," he says. "You just feel if you believe in something so hard, if you truly believe ... the ball will go in." What is left unsaid is Woods' pure relish at the opportunity to demonstrate the full extent of his talent.

"Basically, he's showing off," says Earl Woods. "With Tiger, when he's in a serious situation, it's playtime, in his mind. He's rare."

Awe factor

Nicklaus' domination over his peers inspired some of the game's wittiest hosannas. Chi Chi Rodriguez called him "a legend in his spare time." J.C. Snead said, "He knew he was gonna beat you, you knew he was gonna beat you, and he knew you knew he was gonna beat you."

Still, Woods engenders even more awe from his contemporaries. "I knew Jack was better, but that I could beat him sometimes," says Green. "These guys don't think they can beat Tiger."

Jeff Sluman provides one clue from earlier this year: "We were all watching in the locker room during the restart of the second round at Hazeltine when he hit that shot stiff with the 4-iron from a downhill, sidehill lie in the fairway bunker over the trees into a 30-mile-an-hour wind. There's no man ever in the world who could hit that shot. Everybody just started laughing."

Adds Dave Stockton: "He has shocked us like nobody ever has shocked a group of athletes."

Rodriguez says, "I was a better sand player than Jack or Arnold, a better long-iron player than Trevino, I hit the ball longer than Gary Player. But I can't think of a single thing that I could beat Tiger Woods at, and that's scary."

Sense of destiny

For all his natural gifts and happy turns his life has taken, Nicklaus has always portrayed himself as down to earth, uncomplicated and exceedingly normal. "I'm a lucky guy" is about as far as he goes to explain how it all happened.

"It never ever entered my mind that there was any such thing as destiny," Nicklaus says. "The only thing that was in my mind was that I had a major championship to prepare for, and if I wanted to win it, I better prepare."

Woods, in contrast, has always carried his specialness as a given. He was raised to believe that the forces in his life are, in his father's words, "a directed scenario."

Such a life view has given Woods both an inner calm and a perhaps necessary arrogance. Although some of his personality traits might be considered flaws—he freely admits that he can be cheap, stubborn and cold—he seems to accept them as necessary tools for the life he is destined to lead.

"In a strange way," says Bob Murphy, "I feel that Tiger is more confident than Jack was."

Race

The most obvious difference between Woods and Nicklaus is that Woods is an ethnic minority. It's also the most difficult difference to measure.

Tiger Woods and Earl Woods in 1997.

Tiger's mother, Kultida, tells of early days at junior tournaments when he usually was the only nonwhite competitor. "He felt all the people's eyes on him because he was different, and it made him uncomfortable," she says. "I told him, 'Tiger, you can't tell them how to feel about you. But you can beat them. Win the tournament. Use your clubs, not your mouth. Use that rule, babe.' "

As Woods has become more famous, the subject of race has become more complicated for him to address. When asked how much his racial background has remained a source of motivation, his words lack an edge.

"I think it did as a kid," he says. "I've always known I could play, but some people wouldn't allow me to play or didn't want me to play. That certainly provided extra incentive."

Adds fellow tour player Grant Waite: "I've wondered where Tiger gets his intensity, that real feeling he gives off that he is on a mission, that he's playing for something more than the rest of us. When I watch the Williams sisters play tennis, I wonder the same thing. I have to think it has a great deal to do with race."