Ken Venturi On Rewind

Listening to tapes of conversations with the late Hall of Famer, we learn lessons on how to play golf and how to play life.

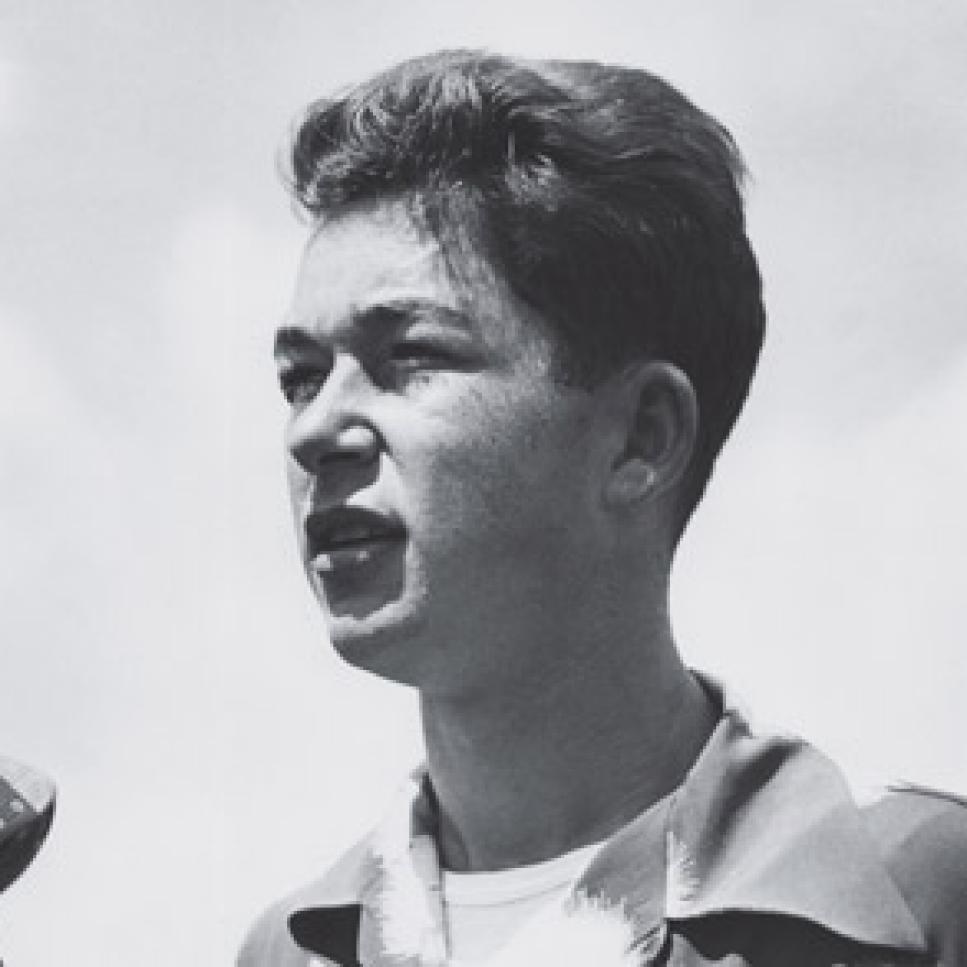

Ken Venturi in 1964, the year he won the U.S. Open at Congressional.

Editor's note: In 2004, Golf Digest Senior Writer Guy Yocom spent time with Ken Venturi for the My Shot series of first-person pronouncements on golf and the acquired wisdom the game bestows. After Venturi's death at 82 on May 17, just 11 days after the 1964 U.S. Open winner was unable to attend his induction into the World Golf Hall of Fame, Yocom pulled out those tapes and replayed the voice of the man who was with CBS' golf telecasts for 35 years. Venturi overcame stammering as a boy and became such a gifted storyteller that it's no surprise there was a wealth of material on the tapes, more than we could fit in that December 2004 issue. We offer the following fresh insights today, with just one repeat: the story of a guide dog from Venturi's Guiding Eyes Classic saving a blind man from the World Trade Center on September 11. Like a lot of Ken Venturi stories, we hope that one is told forever.

STATISTICS IN GOLF ARE MORE MEANINGLESS than in any other sport. I can place your ball on every green at Augusta National and place my ball off every green, and if you let me choose the hole locations, I'll give you a stroke a hole. You "hit" every green in regulation and I missed every green, yet I'll beat you by a minimum of 18 shots. What does that tell you about statistics?

MONEY TALKS. Unfortunately, it doesn't always say the right thing.

DURING MY SLUMP, I shot an 80 at Colonial in 1962 and was embarrassed and disgusted. When I finished, I deliberately switched my scores for the 17th and 18th holes, getting myself disqualified. I regret that; pride and stupidity got in my way. One thing I tell junior golfers is, always post your score, no matter how bad it is. If someone teases you, shrug and tell them, "I did my very best." There's no shame in playing poorly. It's only a game.

AT 13, I played my first full round at Harding Park. I remember we counted everything, and we played fast. I shot 172. I still play fast.

PRESIDENTS CUP, 2000. I'm the captain. We have a nice lead going into singles the last day, but in this game you never know, so I'm looking for ways to motivate my guys. I've planted myself on the first tee when Vijay Singh walks by to play his match against Tiger Woods. I say hello to Vijay, and he ignores me. I thought that was rude, and I get mad. Now Tiger walks onto the tee. I grab his hand and pull him in close, so we're eye to eye. I glanced over at Vijay so Tiger would know the meaning of what I was going to say to him. I said, "I want his ass." Tiger said, "You got it." Well, Tiger beat Vijay that day. We won the Cup. That was very satisfying.

AT THAT PRESIDENTS CUP, captains chose the matchups by going back and forth. They still do that. The punch-counterpunch is exciting, and why they haven't adopted that for the Ryder Cup, I have no idea. Anyway, I won the coin flip and elected to have Peter Thomson, the International captain, choose first. I can tell he's trying to be strategic about where he positions Vijay, because Vijay was Masters champion and their best player. They were behind and would desperately need a point from Vijay. Finally, in the seventh round, Peter announces, "Vijay Singh." I shot back immediately, "Tiger Woods." Peter said, quite audibly, "Oh, s---." He knew he was cooked.

FRANK CHIRKINIAN [the late CBS producer] and I were having lunch at Colonial one day when Ben Hogan stopped by our table. Frank started complaining about his golf game and wouldn't stop. Ben had had enough. "Follow me," he said, and took us back to the kitchen. "I'll tell you the real secret, if you promise not to tell anybody. Deal?" Frank was drooling. "I promise, Ben. I promise." Ben looked both ways, to make sure no one was overhearing. "Elbow to elbow," he said. Frank said, "Huh?"

Ben said, "Keep your right elbow pointing down throughout the backswing, and keep your left elbow pointing down throughout the downswing. Get that down pat, and you'll have a hard time missing a shot."

Frank left for the practice range immediately. I said to Ben, "You gave me the elbow-to-elbow advice 20 years ago. I promised I wouldn't tell anybody, and I haven't. Now you give it to Chirkinian? Hell, that tip will be all over town by midnight."

"Don't worry about it," Ben said. "Do you think anyone will believe Frank when he tells them I gave him a lesson?"

Photo: Golf Digest Resource Center

BEN WAS KNOWN for taking his putter back to his hotel room. I asked him once how he practiced at night. Ben said, "I take the putter back intending to putt, but then I have a couple of drinks and forget about it."

FRANK SINATRA and I were waiting for our car to be brought up after dinner. A kid brings the car and hands me the keys. I reach for my money clip, but Frank pushes my hand aside. "Kid, in the whole time you've been doing this, what's the most you've ever been tipped?" The kid kind of blushes and says, "A hundred dollars, Mr. Sinatra." Frank peels off two C-notes and says, "Here's two hundred. Have a nice night." The young man is ecstatic. Frank, obviously proud of himself, says to the kid, "By the way, who tipped you the hundred bucks?" The kid says, "You, Mr. Sinatra, when you were here last week."

I USED TO PLAY A GAME USING TWO BALLS. One ball, I required myself to draw every shot. The other ball had to be fades, nothing else. If one of the balls didn't do what it was supposed to, it "lost" the hole. In all the years I played this game, the hook ball never won a match, and it usually got closed out early. That's how I learned that the fade is the go-to shot under pressure.

I COULDN'T BREAK 80 WEARING WHITE SHOES. I tried them once, and when I looked down at the ball, all I could see were the shoes. My peripheral vision is tremendous; I can look straight ahead and still detect things behind my ears. White shoes scream. Black shoes whisper.

THE DIFFERENCE between a good player and a bad player is the sequence of their thinking. Say you're playing a hole with water on the right. The good player sees the water and acknowledges it. He immediately turns positive and thinks about where he wants the ball to go. His mind doesn't go back to the water. The poor player is just the opposite. He sees where he wants the ball to go, but his last thought is of the water. The bad outcome becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Always make your last thought a positive one.

TIGER WOODS AT HIS BEST is better than Nicklaus or anybody else at their best. End of story. I distinctly remember a shot Tiger hit at a Masters one year on the seventh hole. The pin was tucked, he had a bad angle, and Tiger being Tiger, I figured he'd probably find a way to make par. He hit a wedge all-out, and it went so high I almost lost sight of the ball. And when it hit the green, it backed up stiff to the hole. Incredible. Jack joined us in the booth later, and I ordered up the shot. As he watched, I asked if he'd ever seen anything like it. "Not in my day," he said, shrugging. At that moment, I thought Jack was conceding that Tiger was better.

WITH THAT SAID, Tiger will never be as dominant as he was in 2000. We won't see him reach that peak again. Even if his game comes around, he's raised the bar for everyone else. There are a lot of guys waiting in the wings. There's also the matter of incentive. Too rich, too good, too easy, too much. I just don't see it.

WE WERE AT PEBBLE BEACH [for the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am], and the camera was stuck on Ray Romano playing the 10th hole. He's down in the hazard hacking away, picking up sticks, grounding his club over and over. It was torture to watch, and I'm thinking, Let's watch some real golf. Finally Jim Nantz thinks of something. "By the way, coming up on CBS, 'Everybody Loves Raymond.' Right, Ken?" And I said, "Well, not everybody." Jim's jaw dropped open, but what could I say? Not everybody loves the way Raymond plays golf.

THE GREAT PLAYERS, with one exception, have not been profane men. I don't remember Hogan swearing, on the golf course or in private. Jack doesn't swear. Jones swore, but not to excess, and certainly not in public. Byron Nelson, never. We all know good men who swear on occasion, so I don't want to get on my high horse about it. But it's best not to make it part of your everyday speech.

WHEN I WAS TRYING to break into golf and needed money, I sold cars for Eddie Lowery [caddie for Francis Ouimet at the 1913 U.S. Open]. I was a terrible negotiator. I wanted to be out of the dealership by noon so I could get to the golf course and work on my game. I didn't have time to haggle. Right out of the box, I'd give customers my rock-bottom price. I'd tell them, "That's the number. That's as low as I can go, and if you find a better deal across town, come back and tell me, because I'll buy two of them." Well, people are good at detecting the truth. They can tell when a person is sincere. I sold a lot of cars.

Photo: Golf Digest Resource Center

ON ALL BUT THE HARDEST chip shots, take the flagstick out. The process of taking the pin out and looking at that naked hole increases your resolve to hole the shot, tightens your focus. It's psychological, and it works.

WHEN YOU GO to the putting green before a tournament round, take only one ball with you. Your putting warm-up is not the same as your full-swing warm-up. The objective is to simulate tournament conditions, meaning one try on each putt.

TOUR PLAYERS TODAY carry at least three wedges, and that's fine. But if you're an average player, you might consider carrying one less and learn to adjust loft on the others by opening or closing the clubface. For one thing, it'll make you a better and more creative player. It'll also free you up to add a club for the 180-to-210-yard shots, which are real bears to play.

WHEN I DESCRIBE a golf shot and gesture with one of my hands, it's always the right hand I gesture with. That's because golf is a right-handed game [for right-handers], not a left-handed game as some people believe. Hogan was emphatic about that. The right hand controls the position of the clubface, generates the speed, applies the touch, everything. All the left hand does is hold on to the club, and hopefully not break down on the downswing.

IN MATCH PLAY it's you against your opponent, and in stroke play it's you against the field. That's how the saying goes, but I never believed it. In stroke play it's you against yourself. To shoot a good score, you've got to be focused on your emotions, your skill that given day and your capacity to take risks. You can't think of the field; it's like battling an invisible man. Take care of your business, and the rest will follow.

SLOW PLAYERS have an advantage over fast players because they can force the fast player to slow down, but the fast player can't force the slow player to speed up. Talkative players have a similar advantage over players who like a quiet atmosphere. A guy like Lee Trevino isn't going to stop talking between shots just because you ask him to.

CHI CHI RODRIGUEZ, Ben Hogan and I were paired together in the first round of a Carling World Open at Oakland Hills. Ben had won the 1951 U.S. Open there, and the galleries adored him. As we walked up the ninth fairway and approached the green, the crowd rose and began a prolonged standing ovation. Chi Chi, who knew this was going to happen, sped 30 yards ahead of us and walked onto the green first. He made a big show as the crowd cheered, removing his hat, bowing deeply, even wiping fake tears of emotion from his eyes, as though the applause were for him. Chi Chi then made it clear that he knew the applause was for Hogan. Even Ben laughed out loud.

HOGAN TO THIS DAY is perceived as having a precise, mechanical, repeating swing that never varied. It's not true at all. When Jules Alexander sent me a bunch of photographs he'd taken of Hogan and asked me to analyze them, I was amazed by all the different follow-throughs Ben displayed. The follow-through is like a blueprint; it tells you what went on earlier in the swing. With the irons, every one of Ben's follow-throughs was slightly different. He was a tremendous shotmaker who made all sorts of small adjustments to make the ball fly high and low, curve to the left or right, spin or not spin when it hit the green and so on. People think of him as a scientist, when he really was a great artist.

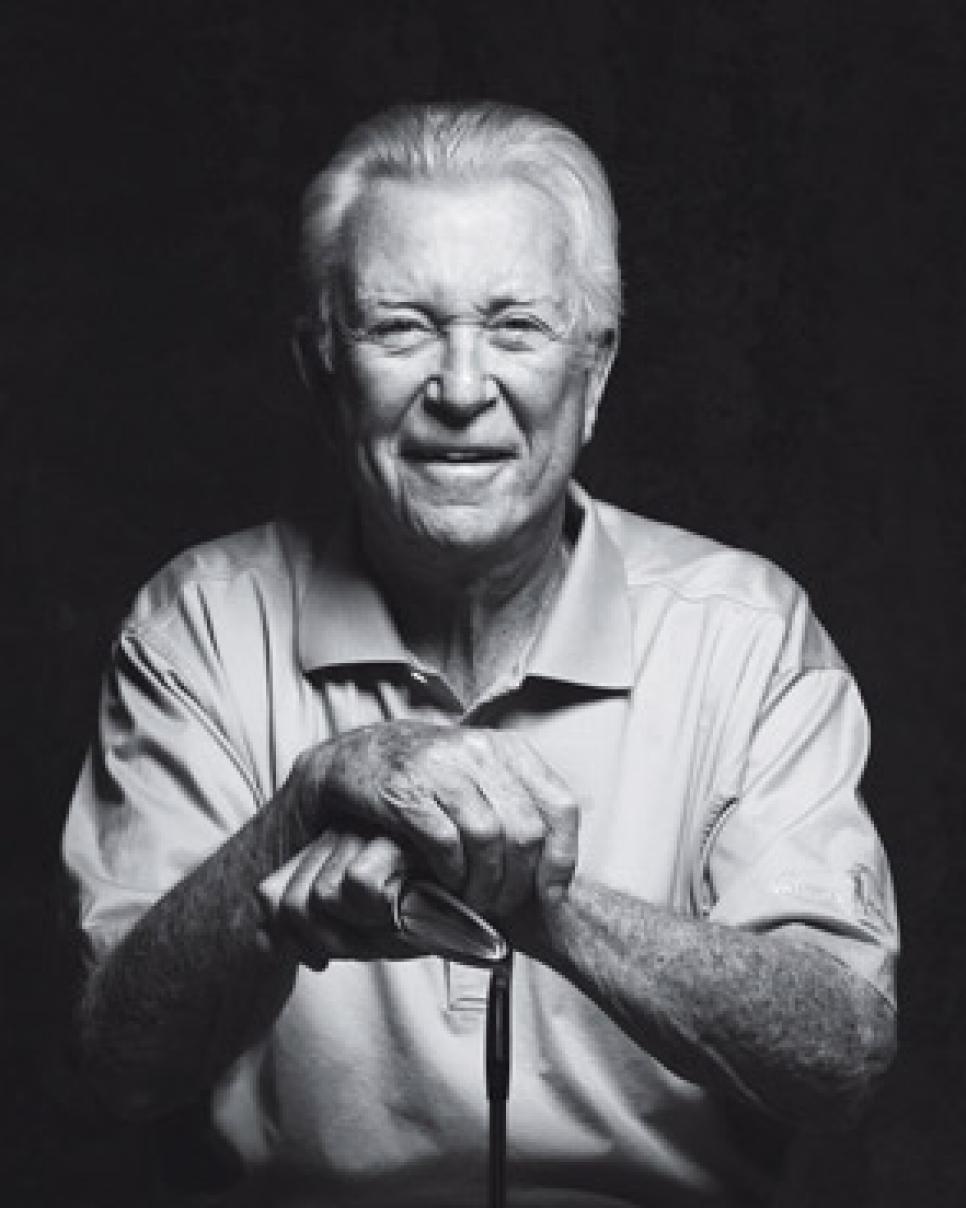

Photo: Robert Gallagher

EARLY IN 1964, my friend Bud Ward gave me a putter that had been given to him by a man named Phil Garnett. Mr. Garnett, who had since died, wasn't much of a golfer, but when he gave the putter to Bud he said, "Save this and give it to someone who really needs it. Tell him it will work." As my comeback continued through the spring, I talked to the putter as though Phil Garnett were alive inside it. "Come on, Philly," I'd say. "We really need this one." And Philly would come through. I won the U.S. Open with Philly, putting beautifully. Philly was the only club I ever owned that had a personality. Today he's alive and well, resting in a trophy case at Burning Tree, not far from Congressional.

IN 1963, Byron Nelson and I teamed against Arnold Palmer and Gary Player in a Challenge Golf match at Pebble Beach. If you can find a copy of the tape, it's worth watching. Byron was 51 years old and had been retired for more than 15 years, but that day he was spectacular. He took the match very seriously and insisted that we plot pre-round strategy and so on. When the day of the match arrived, Byron went back in time and for one day was the old Byron. He chipped in, hit several iron shots stiff to the hole, and basically made the rest of us look like hackers. We closed out Arnold and Gary on the 16th hole. Watching this film, you can only imagine how great Byron was in his early 30s.

MY FAVORITE MEMORY of captaining the Presidents Cup team is something that happened unexpectedly. The competition began soon after the USS Cole was bombed, killing 17 American sailors. I asked that our players wear black ribbons in their memory. Greg Norman got word of that and said the International team would wear ribbons, too. Then we began selling black ribbons to the spectators, the proceeds going to the families of the young people who died. We raised over $400,000 for those families. There were no losers at that Presidents Cup.

FOR 27 YEARS I conducted the Guiding Eyes Golf Classic, an outing in New York that has raised more than $6 million [now more than $8 million] toward giving guide dogs to the blind. It's very worthwhile, because the dogs cost $40,000 each to raise and train. During the September 11 attacks at the World Trade Center, a blind man named Omar Rivera was on the 71st floor of the north tower. Omar didn't think he could make it down through the crush of people, so he asked another man to save his dog, Salty. The man agreed, but the dog shook loose, retrieved Omar, and got them both all the way out. Some time later, at a Guiding Eyes gala at Rockefeller Plaza, Omar came forward and told his story. Toward the end, he said, "This dog came from Ken Venturi." I cry easily enough as it is, but I cried buckets that day.