If a movie were ever made of Lee Trevino’s life, I know where it would start. In El Paso at a hardscrabble course called Horizon Hills where a 23-year-old Trevino arrived at 5 every morning to wash the carts and open the golf shop. One day a white Cadillac rolled in, and Lee went out to get the player’s Wilson tour bag from the trunk and park his car. Out stepped Raymond Floyd, the hottest young pro on tour, in town to play a money match against “some Mexican kid.” In the clubhouse, Trevino showed Floyd to his locker, shined his shoes and got him a Coke. “So who am I playing today?” Floyd asked wearily.

“Me,” said Trevino.

The door opened and a friend of Floyd came in and said, “Hey, Raymond, let’s get a cart and look around the golf course.”

“I don’t need no cart,” Floyd said. “I’m playing the locker-room attendant.”

Trevino beat him the first day and won the money. Lee shot 65 to Raymond’s 67. The second day Trevino beat him again, 65 to 66. There are variations of what happened the third day, but the one I’m putting in the movie is Floyd eagling the last hole to win, finally, and leaving town. Trevino remembers his parting words, “Adios, blankety-blanker.” Once back on tour, Raymond told his fellow pros, “Just wait’ll you see this Mexican when he gets out here.”

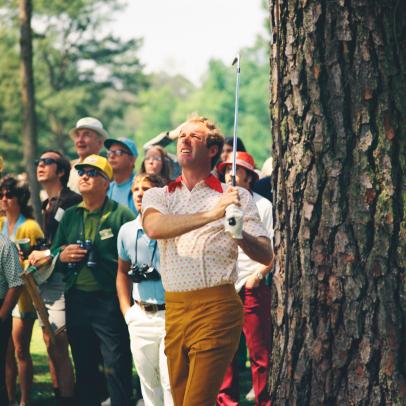

It wasn’t long before he came, and they called him Super Mex. When I first noticed golf, I loved Palmer and idolized Nicklaus, but the one I admired most was Trevino. I never missed a chance to see his sideways swing that repeated a fade, as Charley Price once said of Hogan’s, like a machine stamping out bottle caps. He drove it short and straight—Nicklaus once told him, “Hey, Lee, even I can hit a 5-iron in the fairway every time.” But the shot he hit that Nicklaus couldn’t was a little half-wedge that invariably flew low and hard and zipped to a stop after three bounces, right by the hole. And he could outtalk all of them; nobody in golf before or since ever came close to his imagination, wit and hard-knocks intelligence.

Aneel Bhusri of Workday, the new sponsor of The Memorial Tournament, asked me to interview Jack Nicklaus over breakfast for some friends at The Open this summer. It was a lovely morning, and Jack was on his game, having just been awarded the Citizenship of St. Andrews the day before. I opened with a question not about Jack but about Lee, who had shared the stage and received an Honorary Doctorate of Laws. After all, it was Trevino who played Pancho to Nicklaus’ Cisco on so many stages over the years.

Jack paused a moment as a smile creased his face. “Lee has a great mind,” he said, “an unbelievably sharp mind. I probably have more respect for Lee than any person I’ve ever met in the game. The reason I say that is where he came from, what he did, and the man he became.”

Lee never knew a father and was raised by his mother and grandfather, who was a gravedigger. By age 5, he was picking cotton and planting onions and working in the cemetery at night. He started caddieing at 8 and never took a golf lesson. On days he went to school, he was the best athlete in football, soccer and softball but didn’t make it past the eighth grade. He joined the Marine Corps at 17, never played an amateur tournament and turned pro at 25. He was not a good father the first time around with Claudia I—“Selfishness is the reason I didn’t know my first four children”—but got a mulligan when he met the club pro’s daughter, 11-year-old Claudia II, who sold Trevino lemonade at the Hartford Open and 15 years later married him when he was 44. “She turned his life around, and he became a good father to their two kids, Olivia and Daniel,” Nicklaus said that morning. Lee also won two U.S. Opens, two Open Championships, two PGAs, 29 PGA Tour events and 29 on the senior tour.

Ross Kinnaird

Which brings us to the stage at the University of St. Andrews, Younger Hall, when Lee, 82, knelt before Principal and Vice Chancellor Dame Sally Mapstone, who conferred his doctorate when she touched his head with a university cap that dates back to every graduation ceremony since 1696.

“I’ve devoted my entire life to this game,” Trevino said in his acceptance speech. “It’s the only thing I know how to do. I know I talk a lot, and that’s one of the reasons that I have a difficult time going to sleep at night. It’s simply because I can’t wait to get up in the morning just to hear what I have to say.”

“My career was going downhill like everyone’s career does. Eventually you hit a wall. Regardless of what you do for a living, you get tired of it. Claudia said to me, ‘You think you’re getting too old, and you can’t compete anymore?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ She said, ‘You know your clubs have no idea how old you are.’ I started working at it again, and I started getting better and better.”

Hard work was always Trevino’s secret: the secret of an eighth-grader now with a doctorate.

“I called Barbara Nicklaus and said, ‘Listen, Jack and I are the same age. We’re going to start the senior tour in 1990 at the same time. I’m going to send you a dozen roses every week you keep him home. I played 38 tournaments that year. I sent her 31 dozen roses.”

He talked about his family, the home of golf and his love for the game. “This place is special,” he said. “It’s the greatest honor I’ve ever had. God bless you. Have a safe trip home.”

I was sitting in the balcony at Younger Hall, down the aisle from the newly widowed Gary Player and the honeymooning Tom Watsons. Jack was up front with Lee, and I’m sure Arnold was there somewhere.

If a movie were ever made of Trevino’s life, I know where it would end. On a stage in St. Andrews, with golf ’s greatest generation looking on.