Courses

How Herb Kohler put Wisconsin on the golf map and settled the PGA of America/USGA bidding war over Whistling Straits

Hearing of Herb Kohler's death at 83 this past Labor Day weekend prompted me to dig up the last interview I'd conducted with the corporate giant and legendary golf-course owner. I last saw him in 2019, at Alice Dye's memorial in Indianapolis, but I last taped a Q&A with him four years earlier, a few months before the 2015 PGA Championship at his remarkable Whistling Straits, north of his hometown of Sheboygan, Wis.

It was touching to hear his voice one more time, that deep baritone that's surprisingly soft spoken, with many sentences punctuated by his Santa Claus chuckle. We talked mainly about the origins of his four-course golf empire, the two at Blackwolf Run in the company town of Kohler (named for his family) and the two at Whistling Straits seven miles north. Their roots stretch back more than a hundred years.

When Herb Jr. took over running Kohler Co., in the 1970s, shortly after his father’s death, one of the company's assets was a huge employee dormitory built in 1918. It was scarcely used by the time young Herb became president, so he approved its conversion to a luxury hotel, The American Club, with every room a showcase for Kohler spa baths. It opened in 1981 and quickly gained a five-star reputation.

Among its services was the arrangement of golf for guests at Sheboygan's two courses. Herb, who at the time was a twice-a-year golfer at best, figured any top-notch resort ought to have a golf course of its own, and since the company had an 800-acre wildlife sanctuary at its disposal, he decided The American Club should have a course.

Herb interviewed representatives from design firms for Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer and Robert Trent Jones Jr. before hiring Roger Packard, likely for matters of convenience (he was based close by in Chicago) and economy (he didn't command Nicklaus or Palmer-type design fees.) But Herb said he wasn't keen on the plan Packard produced, so he dismissed him and began his search anew. This time he contacted Pete Dye, whom he had read about in conjunction with the Players Championship at TPC Sawgrass.

Dye walked the property, gushed about the land and took the job. Herb was concerned that the guy used no blueprints or plans, just seemed to create holes while out in the brush. Work started on the course, to be named Blackwolf Run, in 1984 with a scheduled grand opening set for 1986, but two separate 100-year storms washed away portions of several holes, twice, delaying the completion until 1988.

The routing was brilliant, leapfrogging the winding Sheboygan River several times and the completed holes were dramatic and testing. Golf Digest declared it the Best New Public Course of 1988. By then, Kohler already had Dye working on a second 18. "We had to," Herb said. "The American Club was selling out tee times three months in advance. People were calling me personally, trying to get on the course. I don't like to disappoint people."

To fit a second 18 onto the best golf land, Dye surprisingly split up the original 18, using its front nine in creating the River Course. That original nine is now holes 1-4 and 14-18; holes 5 through 13, added in 1990, are perhaps Pete's loveliest stretch of holes on the complex. The original back nine was linked to a new nine built in 1989 to form the Meadow Valleys Course. (Yes, single Meadow, plural Valleys.)

Herb remembered how I had chided him back in 1990 for sacrificing an award-winning course just to accommodate more play, and how he responded that the original 18 would still be available for special occasions, as it was for the 1998 and 2012 U.S. Women's Open.

Even before Blackwolf Run was fully expanded, Herb was already searching for more golf land. He had started playing regularly in 1984, and took a couple of buddies trips to Scotland, where he fell in love with links golf. In 1988, he joined Pete Dye for some rounds in Ireland and became even more enthusiastic.

"I wanted a sand-based links-type layout," Herb told me. "There's plenty of sand dunes along the Lake Michigan shoreline. In fact, Kohler Co. owned 300 acres of dunes right on the lake, but our comptroller donated half of it to the state [as a state park] to settle some dispute. I had to step in before he gave away the other 150 acres, but it was already too late. There wasn't enough land to build what we contemplated."

Instead, he started negotiating with the Wisconsin Electric Power Co., which owned a two-mile-long bluff along Lake Michigan north of Sheboygan, site of a 1950s U.S. Army anti-aircraft training facility. At one time, the power company had planned to build a nuclear power plant on it, but had given up that idea. When Herb approached the power company, a coal-fired plant was still slated to be built on it someday in the future, but since it didn't need to be adjacent to any water source, the company was willing to entertain Herb's offer. After a year and a half of negotiations, Herb got the power company chairman to agree to a deal: Kohler would buy a farm across the highway from the site and swap it (and a bundle of cash) for the lake frontage.

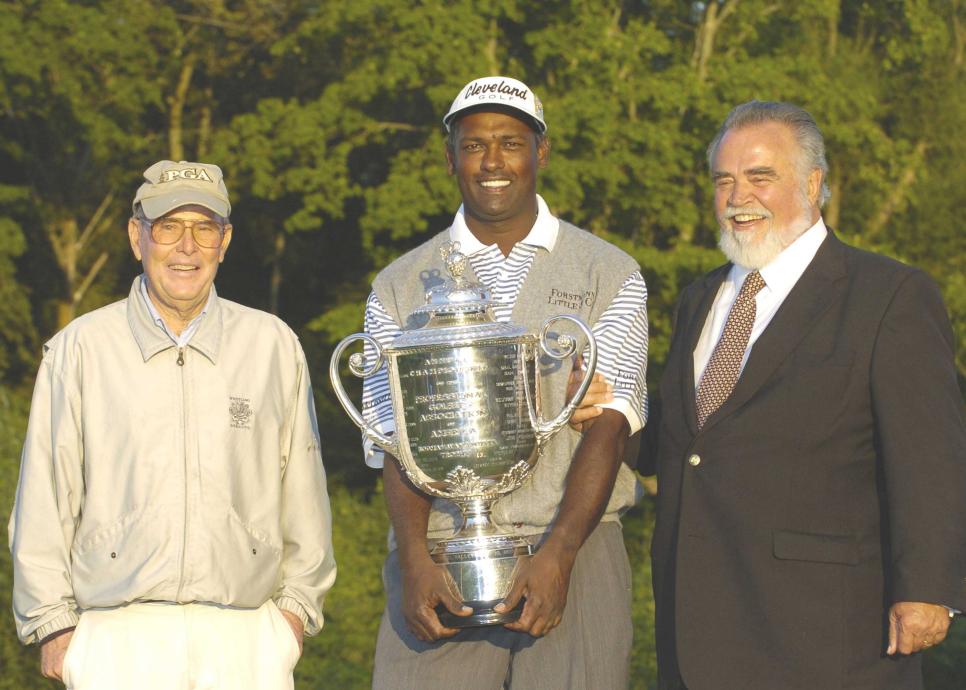

Herb Kohler poses with Pete Dye and Vijay Singh after the conclusion of the 2004 PGA Championship, the first of three times Whistling Straits has held the major.

Al Messerschmidt

The deal was sealed in May 1995, and 20 years later, Herb still remembered that I was the first writer that he and Pete took out to the site. It was a flat plateau, clay not sand, 50 feet above the water, and probably a thousand yards wide. Except for a concrete runway, two concrete buildings and a few access roads, there was nothing else there. Pete was gleeful as we walked the flat, desolate stretch along the lake, a rectangle interrupted only by a deep creek. Herb told me at the time that this would become an American Ballybunion. I was skeptical.

What I didn't know then was that the near-vertical shoreline was eroding at an alarming rate, 10 feet per year. Pete had asked the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which had jurisdiction over the lake front, if he could "lay back" the slope by pushing some of the land inland to form faux dunes. The corps approved but wanted Pete's detailed blueprints. Herb said he laughed at the request. "You're just going to have to live with what we promise to do," he told them.

There were other concerns. The army had used the land for target practice out over the water and live ammunition was still lying about. There were 60 separate waste dumps on the 500 acres, including four deemed to be toxic. Kohler spent nearly $1 million in clean-up before the course construction even started.

The course Pete built was the Straits Course at Whistling Straits, a name that came to Herb one cold blustery day as he walked the site. (A second course, called the Irish, would be built inland in 2000.) The Straits routing was a figure 8, to maximize the number of holes right along the water, much like Pete had done 25 years before at Casa de Campo in the Caribbean. To make it sand-based, and thus springy, sand was trucked in from a farm 10 miles away, 13,000 truckloads in all.

Stephen Szurlej

During construction, both David Fay, then USGA executive director, and Jim Awtrey, CEO of the PGA of America, stopped by to witness the progress and engage in major talk with Herb.

"I don't want to sound braggadocious," Herb told me, "but four months after we opened Whistling Straits in 1999, I had a contract in hand from the PGA of America for the 2004 PGA Championship and a promise from Fay that they were strongly considering us for the 2005 U.S. Open. The USGA was supposed to make its decision that October, but they didn't. I was told the 1999 U.S. Open at Pinehurst had been so successful that there were some in the organization who wanted to return there as soon as they could. So all of a sudden, Pinehurst was our competition. They were 100 years old. We were the new kid on the block.

"The PGA was threatening to withdraw their offer if we didn't accept. It may be the toughest business decision I ever made. What it finally came down to, I figured our tall fescue would look better at a PGA in August than at a U.S. Open in June. We took the PGA offer."

After a financially successful 2004 PGA at the Straits (won by Vijay Singh in a playoff), in January 2005 the PGA of America gave Herb a package deal that effectively froze out most USGA aspirations: the 2010 and 2015 PGA Championships and the 2020 Ryder Cup. Herb agreed to the package, but says he wasn't entirely pleased.

"I wanted the 2016 Ryder Cup," Herb said. "I told Awtrey that I couldn't believe he gave it away [to Hazeltine National] and pushed us to 2020. I told him that was beyond my lifetime. The only reason to take that one would be to put it on my tombstone!"

Ultimately, the COVID pandemic delayed the Whistling Straits Ryder Cup a year, and Herb did live to see the 2021 matches on his beloved Straits Course, the layout he had called, "one of the kinder links the pros will ever play; no weird bounces, no impossible fescue lies, with bent-grass greens that roll faster and purer than fescue."

It is a wonderful legacy that Herb Kohler has left to the golf world.