voices

25 years of memories from Bay Hill, and they all start and end with Arnold Palmer

Editor's Note: This article first appeared in 2021.

Bay Hill has always been one of my favorite PGA Tour stops, dating to 1994.

That was the first time I covered what was then known as the Nestle Invitational. I was researching “A Good Walk Spoiled,” and when I drove onto the property at Bay Hill and parked my car—about a mile from the media center; thanks very much IMG—the first thing I did was go in search of Doc Giffin.

At that point, Doc had only been Arnold Palmer’s right-hand man for 28 years. He would remain by his side for another 28—until Palmer died in September of 2016. My question to Doc when I found him was direct: “Is there any way I can get some time with Arnold this week?” Doc said he would get back to me.

The week was going to be a hectic one: The second thing I did on that Tuesday afternoon was go find Greg Norman. The late Bev Norwood, a rare good guy in the agent business, had told me he had cleared the way and Norman was open to talking to me for the book. I was also supposed to drive to St. Petersburg on Friday and Sunday to cover first- and second-round NCAA Tournament games for the Washington Post. The trip was just under 100 miles—not counting the walk to my car.

Palmer, though, was my primary target. In those days, even though neither played very much anymore, you couldn’t write a book about life on the PGA Tour without talking to Palmer and Jack Nicklaus.

Norman wasn’t an easy out. After he had finished his pro-am round (Bay Hill’s pro-am was on Tuesday) I introduced myself. Norman’s first question was the same one 99 percent of athletes ask upon first meeting a reporter: “How much time do you need?”

I gave him my stock answer, “About an hour.”

Norman, as Nicklaus would do later in the year, looked at me as if he’d seen a ghost. “I don’t have that much time,” he said.

“OK,” I said. “Thanks.” And, as I would do with Nicklaus, I started to walk away.

“Hang on,” Norman said. “Why don’t you come by my house Friday afternoon. We can talk then.”

Great. One important interview set up, one to go.

Sure enough, Thursday afternoon, after I had walked the golf course (and loved it) for the first time, Doc Giffin found me and said, “Can you go to Arnold’s on Sunday morning for bagels and coffee? He can give you plenty of time then.”

Seriously Doc? Can I go to Arnold’s house for bagels and coffee? If IMG moved my parking spot five miles away, I’d get there.

The only hitch was that I’d asked Mike Krzyzewski if I could meet him at Duke’s hotel Sunday morning to talk to him before his team played Michigan State that evening. Talking to Krzyzewski early would make it easy for me to write late if his team won.

I called Krzyzewski and told him I had to cancel our meeting. Trust me when I tell you he wasn’t broken-hearted. “Everything OK?” he asked.

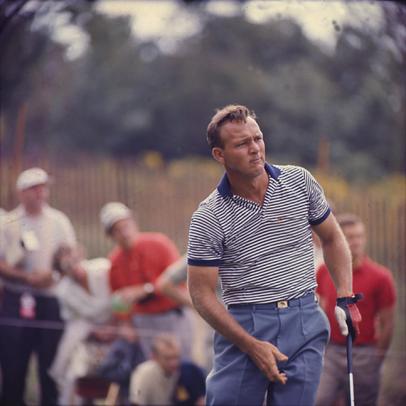

Arnold Palmer stands by the lake at Bay Hill's 18th hole during the first round of the 2013 Arnold Palmer Invitational.

David Cannon

“Yeah, fine, but Arnold Palmer’s willing to talk to me Sunday morning and I have to do that.”

“So, you’d rather talk to a golfer than to me.”

I was tempted to explain the importance of the interview to him. I settled for, “yes.”

And so, at 9 o’clock Sunday morning, Doc and I were ushered into Palmer’s house. Introductions were made and Doc said, “Arnold, you should know, John canceled a meeting with Mike Krzyzewski to be here this morning.”

Palmer looked at me quizzically. “Mike Kachoosko?” he said.

“Jejefski,” I said. “He’s the Duke basketball coach.”

Palmer grinned. “Oh yeah, Duke. That’s the team whose butt we’ve been kicking the last couple years.”

He was right, Wake Forest was in the midst of a nine-game winning streak against Duke.

Gotcha—for the first, but certainly not the last time.

We then sat and talked for two hours. Actually three, because Arnold invited me down to his workshop while he worked on some golf clubs for an hour.

I was late getting started for St. Petersburg and missed the start of the first game. I didn’t care even a little.

Oh, Norman was also terrific, so much so that his then-wife Laura more or less kicked me out of the house because (I think) she was afraid Greg was going to invite me to stay for dinner.

After that, Bay Hill became an absolute on my golf calendar every year. I loved the golf course—I know some players don’t—but there were risk-reward holes all over the place, notably the sixth, a par 5 over water. The 18th was (is) a terrific finishing hole, also with water in play.

From Golf Digest Architecture Editor emeritus Ron Whitten:

I've always been fascinated by the design of Bay Hill, Arnold Palmer's home course for over 45 years (although Tiger Woods owns it, competitively-speaking, as he's won there eight times.) For one thing, it's rather hilly, a rarity in Florida (although not in the Orlando market) and dotted with sinkhole ponds incorporated in the design in dramatic ways.

I always thought the wrap-around-a-lake par-5 sixth was Dick Wilson's version of Robert Trent Jones's decade-older 13th at The Dunes Club at Myrtle Beach. Each of the two rivals had claimed the other was always stealing his ideas. But the hole I like best at Bay Hill is the par-4 eighth, a lovely dogleg-right with a diagonal green perched above a small circular pond. OK, I admit that it reminds me of the sixth at Hazeltine National, another Trent Jones product, but I don't think Wilson picked Trent's pocket on this one, as both courses were built about the same time, in the early 1960s.

For our complete review, visit Bay Hill's Places to Play page here.

In 1995, I flew in for Sunday’s final round—after covering NCAA games on Saturday. Davis Love III was in contention and needed to win to get into the Masters. I had worked closely with Love on “A Good Walk Spoiled” and very much wanted to see him make the Masters. He faded on the back nine and Loren Roberts won for a second straight year.

Afterwards, I sat with Love in the empty locker room. The reason he wasn’t in the Masters was because he’d called a one-shot penalty on himself during the second round of the Western Open the previous year because he wasn’t certain if he had re-marked his ball after moving it at Tom Watson’s request to get it out of Watson’s line.

No one in the group could remember if Love had moved the ball back. Uncertain, he added one to his score and missed the cut by one. If he’d made the cut and finished LAST, he’d have made enough money to be in the top 30 on the money list, which would have put him in the Masters. Instead, he finished about $2,000 outside the top 30.

“How are you going to feel,” I asked, “if you miss the Masters because you called a penalty on yourself you aren’t certain you deserved?”

He shrugged. “How would I feel if I won the Masters and spent the rest of my life wondering if I cheated to get in?”

He won in New Orleans the week prior to Augusta and then finished second to Ben Crenshaw a week later at Augusta.

A year later, I had one of my great moments as a golf writer. Paul Goydos had emerged as something of a cult figure after “A Good Walk Spoiled” came out. He was the ultimate everyman, 5-foot-9, a little bit overweight with what looked like an ordinary swing. He’d been a school teacher for a while before grinding through what was then the Hogan tour and, a year later, through Q school to make the tour. He liked to describe himself as, “the worst player in the history of the PGA Tour.”

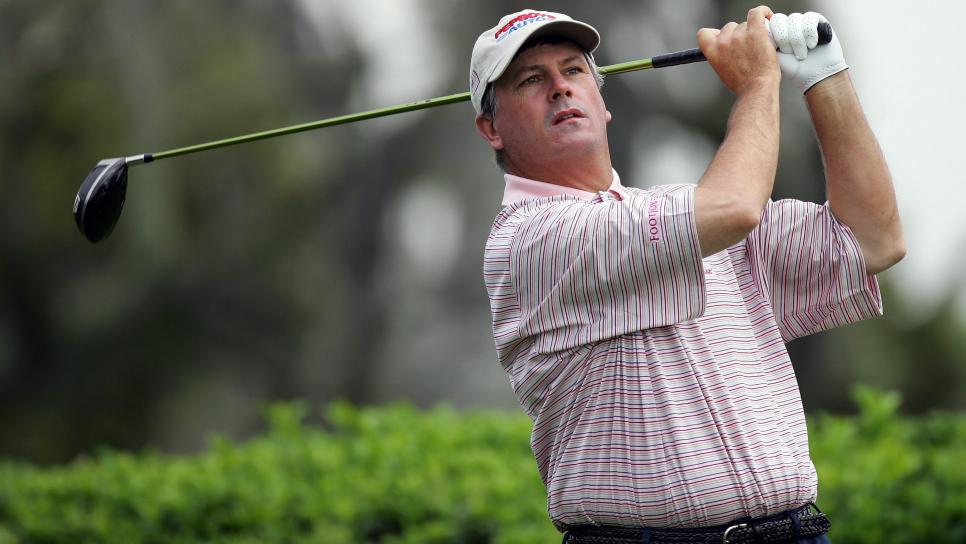

David Cannon

We’d become good friends to the point where almost everyone on tour referred to him as, “your boy.” In fact, Mike Purkey, then my editor at Golf Magazine, had ordered me NOT to quote Goydos in stories. He was my go-to guy most of the time because he was SO quotable.

At Bay Hill in 1996, the worst player in the history of the PGA Tour WON. I walked every step of the way with him on Sunday as he took the lead and resolutely held on. When his ball landed safely on the 18th green with a two-shot lead, I was almost shaking with excitement. Forget the objective reporter stuff. There’s no such thing.

In those days, Dan Hicks was still NBC’s No. 1 guy on the ground; Vin Scully was in the 18th tower. As we walked to the green, Hicks said to me, “Is Wendy here?” a reference to Paul’s wife.

“No, she’s in California,” I said. “The girls (two daughters) are in school.”

“So, does that mean YOU run on the green and hug Paul after the final putt goes in?” Hicks said with a grin.

“Maybe,” I answered.

For the record, I didn’t.

Two years later, a rain-out forced a 36-hole final day. Before the final round began, I rode around with Mark Russell, the PGA Tour official in charge of golf-course setup. There really wasn’t that much Russell could do to make changes with less than an hour between rounds. At the sixth hole though, he picked up the tee markers and moved them up 20 yards.

“That’ll give the boys something to think about,” he said.

He was right. Moving the tees up meant the longer hitters could take a shot at the green with their second shots. There was no way John Daly wasn’t going to take a crack at the green. He did exactly that—six times. He hit one ball into the water off the tee and then hit five straight 3-woods into the water, a la “Tin Cup.”

Unlike Roy McAvoy, Daly didn’t hole his sixth 3-wood, in fact he missed the green way right, hit a six-iron into a bunker and ended up with an 18. Then, he birdied the par-3 seventh.

Tom Watson was one of his playing partners. As Daly picked his ball out of the cup on the seventh green, Watson said, “You know John, that has to be some kind of a record for score differential from one hole to the next: an 18 and then a 2.”

Daly shrugged. “That’s what I’m out here for Tom, to break records.”

A year later, I was walking with the last group on Sunday: Love and Tim Herron, the eventual winner.

On the 14th tee, as Love stood over his ball, a cell phone went off. Back then, cell phones were a fairly new phenomenon. Love backed off. The guy with the phone answered it. When everyone began screaming, “hey, hang up!” the guy put up a finger to indicate he just needed another minute.

He didn’t get it.

It was the next year—2000—that the tournament became the Tiger Woods Invitational. He won it four years in a row and eight of the next 14. Three-and-a-half years after Woods’ last win, Palmer passed away at the age of 87. In the wake of his death, there was concern about the tournament’s future. After all, many top players came to play because of Palmer’s presence.

Champion Tiger Woods and Arnold Palmer share a laugh during the trophy ceremony of the 2013 Arnold Palmer Invitational.

David Cannon

The Florida swing has changed considerably over the years. The Honda Classic, which had once been the tournament most players skipped, had grown in stature since it finally found a home at PGA National Resort. With the Players Championship coming back to March, would the top guys still come to Bay Hill?

Yes. Palmer’s grandson, Sam Saunders, who has been a PGA Tour player, has done a remarkable job of stepping into Palmer’s unfillable shoes. The PGA Tour helped by making the API one of three invitationals that gives the winner a three-year tour exemption (instead of two) and 550 FedEx Cup points, instead of 500.

That morning in Palmer’s house, he expressed regret to me that the tournament needed to have a title sponsor. “I’m not knocking Nestle but I’d really like to be like Jack’s tournament [the Memorial],” he said. “Have a presenting sponsor but have Bay Hill in the title.”

Two years later, he got his wish: The tournament became the “Bay Hill Invitational presented by Mastercard.” In 2007, it became the “Arnold Palmer Invitational presented by Mastercard.”

Palmer’s name should always headline the event. I could go on for a good long while about other memories I have from days spent at Bay Hill. I hope to spend many more there in the future. And I’ll always think back to hearing Palmer say, “Kachoosko.”