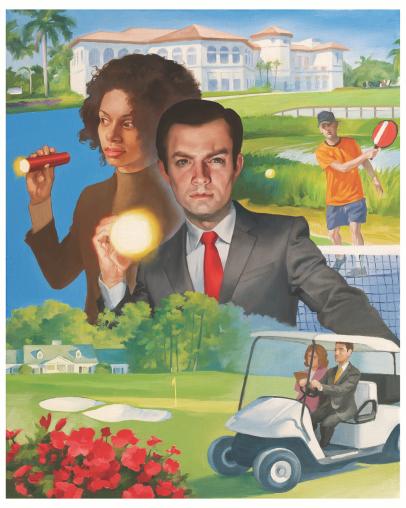

Creating Opportunities

How to get a job in golf: Eight stories from people who found a way to live their dream

Life as a shaper has taken Angela Moser all over the world. It’s an artist’s work: The bulldozer is the brush.

“A shaper is a heavy-equipment operator with a passion for and an understanding of golf and golf-course architecture and its history,” Moser says. “A shaper doesn’t just work off architectural plans but develops ideas and tries to integrate the golf course into nature. It shouldn’t be the other way around. Nature shouldn’t be too adapted for the course. We’re minimalists. We’re trying to not change the world.”

Moser, who lives mostly nomadically, loves her work—starting with an idea and playing with it, trusting her instincts, sculpting the dirt and feeling the ground until it’s ready to be enshrouded in greenery.

“It’s a process,” she says. “You work on it and jump out of your machine to look at it. You walk from different directions and check the look and playability from different angles. You really chew on it until you can’t find anything that you don’t like. Besides, you play a bit of dirt golf in the process.”

As a teenager, Moser played in tournaments and remembers a particularly gnarly par 3 over water. “This kicker slope fed into this really tough pin position,” Moser says. “I thought, This is the coolest thing ever. Everyone else was like, ‘What’s wrong with her? What a weirdo.’ ”

She learned that her passion had a name: golf-course architecture, though it wasn’t a popular field in her native Germany. After getting her degree in landscape architecture and working at an Austrian design firm, Moser believed that there must be “something else out there.” She Googled “best golf courses” and, after some digging, sent an email to Tom Doak asking about internships. He answered, offering her a position with the Renaissance Club’s design in Scotland. “He made sure I understood the internship was on a construction site,” she says. “I was like, ‘I can’t wait.’ ”

It was her first time using a sand pro, excavator and dozer. “That was my start in the dirt,” Moser says, “getting a taste of what shaping and building a golf course means.”

To those searching for their big break, Moser’s advice is to find people whose work you admire, whether through Instagram or Twitter, and message them. “Share your thoughts, your interests and explain what you’re looking to do,” she says. “I wrote one email, and it changed my life. You only have to have the courage to make that first step.”

TENDING TO THE GRASS

LAND THAT I LOVE The best part of being a super? “You get to work with Mother Nature,” says Yale’s Jeffrey Austin.

“The opportunities are abundant in our industry right now,” says Brian Green, director of golf-course maintenance at Lonnie Poole Golf Course at North Carolina State University. “There’s a shortage of maintenance employees all the way from general labor to supervisors.” This staffing issue can be attributed to pandemic-related labor shortages that have been felt across all industries, as well as a reliance on foreign-born workers who are no longer available for employment because of changing immigration policies.

As a university course, Lonnie Poole relies on students who enjoy being around golf, but they often don’t know how to keep the course running. Like other courses, Lonnie Poole also hires a team of grounds technicians who do everything from daily course setup to running equipment. “It’s a great way to start,” Green says. From there you can specialize, often by learning on the job to become an irrigation or equipment technician, pesticide applicator or horticulturalist. Though greenkeepers don’t require any specific education, experience in sports or landscaping helps. Many grounds technicians who work their way up to become superintendents pursue higher-education degrees and certificates in golf-course management. Green wasn’t sure what he wanted to do after high school, so the Durham, N.C., native took classes at a community college before learning about NCSU’s turfgrass-management program and finding his calling.

“As is the case with most occupations, there’s a little bit of science and a little bit of art involved,” says Jeffrey Austin, superintendent at the Yale Golf Course in New Haven, Conn. “It’s a job that you can’t know everything.” Austin came to greenkeeping in his mid-20s, later than most, he says. Earlier he studied political science and wound up working for a senator. After one year he realized he hated being in the office and took a summer job working at a course to make ends meet. He thought, You can’t grow grass for a living! Once he realized he could, he went to school for turfgrass management and has spent 18 years working on various courses, including four as an assistant-in-training superintendent at Augusta National.

Like so many superintendents, Austin agrees that the best part is working with Mother Nature. “You have to trudge through a lot of mud to get to the ultimate goal,” Austin says. “But I’m still doing it. I still have my work boots on.” As a bonus, “there’s lots of free golf,” Green says. “We try to look out for other people in the industry.”

MYSTERIES OF THE DEEP

TREASURE HUNTER Brett Parker retrieves roughly 1.3 million golf balls from water hazards each year.

In the pitch black of zero-visibility water hazards, diver Brett Parker follows a grid pattern, often for up to 12 hours at a time, feeling for golf balls with his hands and avoiding logs, broken bottles, barbed wire and 60-pound snapping turtles. It’s an art, he says, and one that requires experience. Even without markers or sight, you must always know where you are and where you’ve been, or you’ll miss a ball, which means fewer dollars in your pocket. “When I get into it,” Parker says, “I can stay in all day. My philosophy is, if I don’t get them, someone else will.”

Growing up in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Parker had never heard of letting golf balls sink; the second they hit the water, kids would snag them for a penny. It wasn’t until he moved to Florida in 1986 and saw players haphazardly hitting balls into the water one after another that he thought he had an opportunity. Only one complication stood in the way of his lucrative career plan: alligators.

“Coming from Africa, we dive with crocodiles. Alligators are generally more docile.” Besides, he says, once he’s in the water, “I find the dark comforting. If I can’t see anything, then they can’t see me.”

Parker started diving at 16 while working at a cattle ranch in Rhodesia, salvaging valuable items like fallen boat outboard motors. “When you’re young, you’re kind of stupid, not seeing the value of life,” Parker says. “But recovering a $60,000 boat engine could net you $1,500, the equivalent to five months’ salary in those days.” When he moved to Florida in his 20s, he attended diving school and earned his license.

Parker, now 62, is one of only a few (five, he reckons) skilled professional golf-ball divers in the country. “There’s no young people coming in,” he says. “We are a dying breed.”

If you stick with the profession and hone your skills, you can find, as Parker does, 1.3 million balls annually, bringing in about $150,000. As far as equipment goes, the tools range from diving gear (license, regulator masks, fins, weight belts, suits for different temperatures, scuba tanks and catch bags for collecting golf balls) to a truck and trailer. Because Parker spends so much time under water immersed in hazards from poisonous cottonmouth snakes to bacteria to herbicides, he always carries a snake-bite kit, Sudafed, Vitamin C, potassium (for cramping), Pepto Bismol and hydration drinks. He also makes sure to get frequent tetanus shots. To dig through muddy waters where the balls are often trapped and hidden, he layers garden gloves over surgical ones to keep his hands warm and prevent minor cuts and infections.

His best find? A 130-year-old ball from 1895, which he did not sell. He has also discovered a Mercedes, empty safes and guns. (He often has to pause his work to call the police.) As he views it, he’s providing multiple services to the community, making the waters a bit safer (and litter-free) for all those snakes, turtles—and gators.

PLANNING THE JOY

Before starting his golf-tour operating company, Jason Kauflin played all the best courses in Wisconsin. “I was a stay-at-home dad,” he says. “I was raising kids.” When his buddies asked him to plan a guys’ trip, he was all too eager. “I had all the time in the world to organize this.”

By 2008, his group had grown to 44 players. He was still in “small-group mode,” signing each person up for a rewards card with the rental-car dealer, for example. He laughs about those days now. This year, he’ll organize 90 groups through his company, Wisconsin Golf Trips, with $1.8 million in gross sales. He learned how to run his business by taking online courses in subjects like search-engine optimization and website design, and, of course, by playing golf, befriending club pros and building relationships across Wisconsin.

“Never having started a business before, you have to be willing to just say, ‘I don’t know where to go or where to find this,’ ” he admits. “I treated the business like it was Home Depot and said, ‘I don’t know how to do this.’ ”

Kauflin knew he would be running his business mostly online, so he focused on nailing the design of his site. For example, his homepage features a photo of himself smiling on the course, leaning against his clubs, connoting, he says, the kind of personalized attention he likes to give his clients, which could be a group of high-rollers flying private or a single player with a modest budget. He spends most of his time writing the pitch itinerary email he sends up-front. He pays close attention to the writing style, filling the emails with links and photos. Though he’s usually in communication with only one head planner, this email is the way he must win over the group. “The golf courses sell themselves,” Kauflin says. “You’re buying me. You’re buying the fact that you’re going to trust me with your money and your time.”

Kauflin is an in-bound operator, which means he brings people to Wisconsin. “I have many friends who are solely out-bound operators, taking you to out-bound destinations,” Kauflin says. “I don’t feel comfortable booking a group unless I know the area.”

Five years ago he joined the International Association of Golf Tour Operators and has teamed with colleagues in other parts of the country to expand his business to places he frequents like Nevada, Minnesota and Michigan. He even has industry contacts with whom he collaborates in Northern Ireland and St. Andrews, Scotland, two places he knows well. Kauflin usually books trips a year in advance and is orchestrating a trip for, often, a dozen friends with their own ideas of the perfect golf trip. “I get to know these guys really well,” he says. “I’ve made some great friends doing it that way. I text them all the time.”

ENJOYING THE SCENIC ROUTE

David Edel has always known what he wanted to do: work in golf and give back to the game he loves. Perhaps paradoxically, and by his own calculation, he had every job in the industry—from caddieing to instruction to greenkeeping—before finding his niche designing his eponymous line of custom putters, wedges and irons. “We have to be stewards of the sport,” Edel says. “I look at what I do as helping people enjoy and be fulfilled playing golf.”

Edel got his first golf job in high school working as a “bag-room boy,” cleaning up and working around the shop of his community’s nine-hole course in Reedsport, Ore. He double dipped as a greenkeeper in the summers, something he later did in college to fund his education. While at the University of Oregon, he worked at Fiddler’s Green Golf Center in Eugene, then the world’s largest golf shop at a whopping 15,000 square feet. “I learned retailing, clubfitting and customer service there,” Edel says. “The owners were amazing people. It was a family-run operation. I learned the art of talking to people about golf clubs and learning everything that’s in the golf world.” After college, he worked a variety of teaching and assistant-pro jobs across the country. In the 1990s, he spent a few years teaching golf in Central and South America: Colombia, Panama, Honduras and Argentina. He didn’t speak Spanish at first but eventually gained fluency. “I knew teaching was my calling,” Edel says. “The process of learning how to teach without speaking the language made me a better teacher.”

In 1996, Edel got married and decided to return to find a more settled job in the States. “I was kind of tired,” he says. “I never saw a winter. I never saw a downtime because I was always chasing the sun.” He joined the family hotel business but hated it from day one. He missed golf. He started tinkering around with making his own putters. “I always loved club manufacturing, repairing equipment all through this process.” In all of his jobs, as a teacher or assistant pro, he always jumped at the first opportunity to mend clubs. “I grew up in a family fishing resort,” he says. “You had to repair everything. So I kind of had that aptitude to fix stuff.”

By the end of the year, he founded his company, Edel Golf, now with 450 fitting accounts worldwide and distribution across 12 countries. “If I knew how long it would take to get where I am, I still would’ve taken that journey. I didn’t think it would be this hard at times. But I’ve loved every minute of it,” Edel says. “I’ve seen the world because of golf.”

LIFE IN MINIATURE

David Backus, then 33 and itching to get out of his role in corporate finance, started plotting his dream course on vacation in Myrtle Beach, where he and his friends spent much of their time playing miniature golf. He approached his accountant sister, Jessica Backus, then 29, with the idea to open a miniature golf course in Austin where he lived. The pair researched extensively, reading everything to be found on the Internet about managing a mini-golf course. They took a business plan to their cousin’s husband, who had expertise from starting his business. “He said, ‘The best you’re going to do is 50 percent of what you think you’re going to do.’ ” David and Jessica scaled down their expectations for the first year, resulting in a more reasonable business plan. Still, they got declined from all 10 banks they pitched, saying it was too risky and a “niche” investment.

After regrouping, David and Jessica recruited the financial help of their parents. Together, their assets secured a line of credit. The course alone was $300,000. Because they opted to buy the land they operate on, with the addition of lighting and leasing, the total investment was $1.4 million.

Plan secured, the brother-sister duo flew to Wildwood, N.J., to visit the manufacturer they had chosen to build their course, a step that could have been saved by flipping through a catalog, but David and Jessica wanted to try out their products. The day before their meeting, they even “broke into” every mini-golf course in Wildwood to inspect the boulders and waterfalls, which, though inactive, proved especially intriguing. “They make them look so lifelike, but they’re actually manufactured,” David says. “We got to see exactly how they worked when they were off. It was a lot of checking over our shoulders, but we were so excited about our project. It was worth the risk.”

Next, David recruited his golf buddies, who work in plumbing, construction and electrics, for help. “They helped me get deals, and I was able to trust them,” he says. “We knew it was expensive to build but inexpensive to run. So all of our costs were up-front. We’ve turned a profit ever since we opened.”

Today, five years after opening Duke’s Adventure Golf, there’s still a lot, particularly regarding maintenance, that comes down to trial and error. David says the best part about the job is meeting the people who come to play. Seeing kids light up at their outdoor-themed course brings him joy.

“Take the risk when you’re young,” David says. “When something goes wrong, there’s always a way to fix it. The way might not be noticeable; it might be very difficult. But at the end of the day, whether it’s through family or networking, there is someone who will think that your dream is a good idea.”

FINDING YOUR VOICE

TALKING A GOOD GAME Tricia Clark says golf and her podcast have turned her into an extrovert.

Tricia Clark had never played golf before, yet she had helped companies raise hundreds of thousands of dollars through charity tournaments in her profession in human resources serving on golf committees, a gig she fell into as a lover of nature. It wasn’t until she found herself on the 12th hole at the PGA Tour’s Valspar Championship watching Tiger Woods on his 2018 comeback tour that she decided she must give the game a shot.

“I was the only African-American female in the grandstands,” says Clark, who was working in human resources for Welbilt Inc. at the time. “I’m screaming at the top of my lungs. He makes his birdie putt. He literally tips his hat to me. That was it. I was like, I’ve got to learn this game.”

Four years and one hole-in-one later, Clark is a “golf ambassador” with the mission of getting more women and people of color involved in the game. She does this through her social-media platform; for example, she’s a member of one global golfing Facebook group with more than 30,000 members.

“I post a picture with every single person I play golf with,” she says. “It’s a memory; it’s a connection. You always want to make a connection with someone you come into contact with through golf. You never know how that can benefit you in the future.”

Clark’s life has been changed by one such serendipitous golf connection. In 2021, someone she played golf with suggested her to Manny Upshaw, president of the golf league Golf LA. Upshaw was looking to start a golf podcast with Chris Sifford, the great-nephew of Charlie Sifford, the first Black golfer to play on the PGA Tour. The result was “The Golf Locker Room” podcast, about all things in the game’s minority community. The podcast celebrated its one-year anniversary in July. Every Wednesday at 8 p.m., Clark, Upshaw and Sifford log in from their home studios in Florida, California and North Carolina, respectively, to record live. All it takes is a microphone, camera, lighting, research and “chemistry.” Clark is in charge of leveraging the relationships she builds on the golf course to find and source guests while providing the female perspective.

This spring, she finally quit her day job working as an executive assistant for PricewaterhouseCoopers (where she also served on the golf committee) to focus on her golf career full-time. In addition to the podcast, she also runs her own businesses booking travel and golf trips, and coordinating and fundraising for tournaments and clinics, plus more projects on the horizon. She also founded a nonprofit, Queens and Kings on the Greens, to introduce new players to the game and to offset financial barriers for youth golfers as well as high school and college students looking to pursue their professional careers on the tour.

“I’m an introvert, but golf and the podcast have made me an absolute extrovert,” Clark says. “There’s no fear in speaking. There’s no fear in approaching anybody else. There’s no fear in introducing myself to a stranger, and I love it because it was probably always me—but it took this passion to bring it out.”

PUSHING GOLF’S BOUNDARIES

A GOOD FIT Entrepreneurial clothing designers like Michael Huynh have found a receptive audience in golf.

After presenting a sales pitch to 50 people in 2017, fashion designer Michael Huynh went to his office to catch his breath. He ended up suffering a seizure and was rushed to the ER. Less than 72 hours later, it happened again. “I lost myself,” he says. “I alienated my health.” His doctors diagnosed him with hypertension. He understood the truth in what they told him: “If you don’t stop, you’re going to have a stroke and die from this.”

His physical therapist suggested he take up golf, which Huynh credits as saving his health, his love for designing and, yes, his life. “I’ve learned a lot about myself through the game of golf,” Huynh says. “You learn the pressure you can handle. You learn to cope with frustration. It teaches you how to breathe and how to slow things down.”

Inspired and on the mend, Huynh decided to blend his passions of fashion and golf for his next entrepreneurial endeavor; he took his sartorial aesthetic—his love for edgy, experimental streetwear that tells a story—to the golf world. He founded Students Golf, a golf lifestyle and apparel brand, in 2021. His designs, which range from sweatshirts emblazoned with witticisms like “Students Dept. of Swing Corrections” to tees depicting club-wielding skeletons rising in flames, speak to his previous fashion life as a contractor for skate and streetwear brands like Vans, Burton, Superism, Publish and Sk8Shop. Since he got his start in 1998 studying fashion from his mom (who was a production manager for high-end brands like Nine West and BCBG), he has worked for the likes of The Weeknd and Kanye West. In founding his brand, Huynh did everything, from financing to marketing.

“To obtain the purest form of brand identity, you’ve got to do it yourself,” he says, “because down the line of growth, you’ll know how to advise every aspect of the brand. Then you can start hiring people.”

In the apparel and e-commerce markets today, Huynh says the move is to build a brand you love with a cohesive identity that’s curated through the details, from the product packaging to the website graphics. Then, plan to sell it within 10 years. “When you’re about to sell, you show the feeling that you have not hit the ceiling yet,” he says. “Show that you have so much more to do.”

With Students, that timeline is progressing quickly. He planned on pitching his newbie brand to 10 stores max, but after a few select phone calls, word spread. “Everyone said, ‘Michael’s back. Let’s support him.’ ” Seemingly overnight, Students landed 125 accounts—and growing.

As you’ve just read from these fascinating individuals, there’s no one way to get a job in golf—especially as the industry evolves and adapts to new technologies and pioneers push the sport on environmentalism and accessibility. Whether you’re newly graduated or looking to change careers, if you love golf and want to work in the business, these stories offer framworks for how to marry your skills and passion for the game. But like Moser says, blueprints offer only a guide; the fun part is hopping in the bulldozer and playing in the dirt.