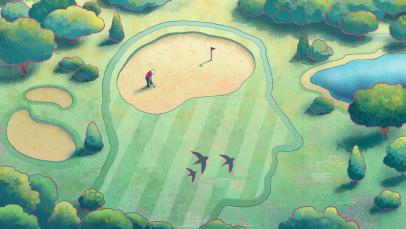

Golf + Mental Health

Pro golf is approaching its own mental health reckoning

Editors’ Note—This story originally ran in October 2021, as the world of professional golf was returning to a schedule of tournaments that resembled what existed prior to the onset of COVID-19. Yet, in the transition to a post-pandemic life, many within the game had awaken to a realization that things weren’t ever actually going to be the same. A discussion surrounding mental health had emerged not just in golf but sports in general after years of subjugation and repression, high-profile athletes Simone Bilas and Naomi Osaka beginning a national and international conversation around the issue.

The article below explores this topic as it relates to golf, identifying the unique pressures felt by tour pros under the spotlight often living lonely, solitary lives. Clearly, addressing these concerns had become a priority, as we see in the stories told by Matthew Wolff, Will Wilcox and Erik van Rooyen, among others.

While the landscape of the sport has changed much in the ensuing 12 months—Wolff has since signed with LIV Golf and is playing in its events—the stresses this article and accompanying podcast probe remain as real and relevant as ever.

Matthew Wolff was living his dream. He had parlayed a decorated amateur career into instant PGA Tour success, winning his third start as a professional and taking top-fives in his first two major championships. His sui generis swing and gregarious personality had quickly made him one of the most popular players in the world. Endorsement deals with companies like Nike, TaylorMade and Gatorade supplemented millions in on-course earnings. On the surface, Matthew Wolff had it made. On the inside, Matthew Wolff was suffering.

The nadir came last April. Standing where every golfer wants to one day stand, Wolff wanted to be anywhere besides Augusta National Golf Club. He sat on a bench just right of the 17th tee on Friday afternoon and buried his head in his hands, desperate for a disastrous Masters to reach its merciful end. It did, but not before another embarrassing body blow: He signed an incorrect scorecard and was promptly disqualified from the biggest tournament in the sport. He honored a commitment to play alongside Collin Morikawa two weeks later at the Zurich Classic but was there in body only. The pair missed the cut, and Wolff decided to do something that shouldn’t be as extraordinary as it was. He stepped away. This injury wasn’t visible to the naked eye or even an MRI, but that didn’t make the wound any less real or any less painful. So, at age 21, with the world at his fingertips, Wolff took two months off to focus on a simple goal: His happiness.

The discussion surrounding mental health has emerged from the sports shadows after years of subjugation and repression. Just two weeks ago, Carey Price, perhaps the finest goaltender in the NHL, took a leave of absence not for an alcohol or drug addiction, not for a gambling problem, but for his own well-being. He wasn’t the first. In April, tennis megastar Naomi Osaka announced she wouldn’t speak with reporters at the French Open. The ensuing debate over an athlete’s responsibility and the role of the modern media diverted attention from a young woman going through something profound. After losing in the U.S. Open she, too, decided to take a hiatus from the sport that made her an icon, for even the successes brought no joy: “I feel like for me recently, like, when I win, I don’t feel happy,” she said. “I feel more like a relief.”

At the Olympics, Simone Biles was set to further cement her status as the world’s greatest gymnast until she put forth an uncharacteristically wobbly performance in the preliminary rounds. “I truly do feel like I have the weight of the world on my shoulders at times,” she wrote on Instagram. Days later, she withdrew from the individual all-around, the event that turns gymnasts into legends. Her event.

Both Osaka and Biles struggled with the same individual-sport challenges that confront today’s professional golfers—even the most established ones, who travel around the world playing for eye-popping purses.

Especially compared to women's golf, where the financial opportunities are fewer and the strain of making meaningful income is felt even by established veterans, the PGA Tour is a pinch-yourself gig. But it's a pinch-yourself gig that brings baggage of its own. In the same way Osaka and Biles confessed feeling isolated as they further ascended their sport’s ladder, professional golfers are beginning to acknowledge and address the toll the game takes on their psyche and well-being.

“You can feel like you’re on an island because you’re the only one performing,” says Dr. Rick Sessinghaus, who, in addition to holding graduate degrees in sports psychology, has coached Collin Morikawa since he was 8. “The spotlight is always on you, and it’s very easy to judge whether a performance was a success or a failure. In team environments, you can have a poor game but still be on the winning team, and you get lost in the shuffle of everything. The success and failure isn’t quite as obvious—not only to you, but to coaches, parents, and everyone else watching.”

Everyone else watching. Therein lies a crucial difference between junior or amateur golf and the PGA Tour: not only is your performance essentially graded at the end of each day and each week, but other people see those results and care about those results. Players don’t want to let down their inner circles, of course, but there’s also an underlying knowledge that the general public is paying attention. So are sponsors. So are the media, who will stick a microphone in your face and ask about your failures minutes after you failed. Consider the anxiety-producing prospect of having to constantly answer for why you had a shitty day at work, or logging onto social media and seeing vitriolic ridicule directed at you for miswording an email.

Matthew Wolff sat frustrated on the 17th tee during Friday's second round of the Masters. No long after, he'd be disqualified from the 2021 Masters for having signed a wrong scorecard.

Ben Walton

To these reporters and fans and keyboard warriors, a professional golfer exists only through the lens of professional golf. Family life, off-course hobbies—those are all well and good, but they’re secondary. Fun little anecdotes that add context to the only thing that really matters: his on-course performance. It’s astonishingly easy for this line of thinking to bleed into the player’s psyche. He begins to judge himself by his scores and his finishes. He wraps up his self-worth in birdies and bogeys.

“Let’s say a guy is on-site for seven hours,” says Sessinghaus, “and then he does a media thing, they go to their hotel, they see themselves—the reminders are constant that they are a golfer. When everything is viewed through that identity as a performer, then the only filtering that comes back is did I perform well or not? And if I did not, that bleeds into your identity as a person. Not just a golfer. Can I have a poor tournament, and still be happy with myself? That is a huge challenge. It’s so cause and effect. It’s, I’m the one who missed a cut. I didn’t make a check. I played so bad. When you use the word ‘I’ a lot, that becomes your identity.”

'When everything is viewed through (your) identity as a performer, then the only filtering that comes back is did I perform well or not? And if I did not, that bleeds into your identity as a person.'Dr. Rick Sessinghaus

Motivational structures become skewed. Parents might dream it, but no child picks up golf with fame and fortune in mind. A kid wants to whack that ball, to improve, to spend time with family. Experts call this intrinsic motivation. Then college scholarships enter the picture. Turning professional. Winning tournaments. Moving up the World Ranking. A private jet. Somewhere along the way, the motivation shifts to extrinsic. Golf morphs from a passion to a means to an end.

“Doing it as a job or for a living—that's when the joy goes out of it and that's when you lose your innocence,” Rory McIlroy said at the Tour Championship. “There's a part of that that goes the further along you get in this professional career.”

As players turn pro and taste success at a younger age, that problematic shift is happening earlier. For Wolff, it came shortly after he finished second in the 2020 U.S. Open as a 21-year-old. For Akshay Bhatia, a junior phenom who eschewed college to turn professional immediately, it happened while still a teenager. At 19, Bhatia qualified for the U.S. Open at Torrey Pines and made the cut—a remarkable accomplishment at such a young age. After a Saturday morning 73, a dejected Bhatia told reporters that he had a terrible time.

AT 19, Akshay Bhatia qualified for the 2021 U.S. Open and made the cut, but said he had a hard time enjoying himself and understanding the opportunity he had created for himself.

Ezra Shaw

“I just have a hard time enjoying myself and understanding the opportunity I created for myself and just the atmosphere,” Bhatia said. “I should enjoy it a lot more than I do. I just didn't have fun today, which really sucks because a lot of golf is score-oriented, and when you're not playing well, it feels like it sucks.”

Cruelly, feeling pressure to perform makes performing that much harder—a downward spiral of anxiety. Viewing each round as vitally important to your self-worth triggers a physiological response that is profoundly counterproductive.

“When players panic, the emotion is fear,” says Dr. Michael Lardon, a clinical psychiatrist who has worked with Phil Mickelson, David Duval, Will Zalatoris and dozens of other tour professionals. “It’s called ‘autonomic hyperarousal.’ You breathe too fast, your blood pressure goes up. If you’re in the ocean and a great white shark comes, you’re fearful and you’re worried. You go into fight or flight mode. You’re out of there, you get to the beach. But what if you’re on the golf course? And you have to hit a 3-wood into a par 5 in front of 20,000 people, and you have that going on? It’s an untenable situation and it happens a lot more than you think.”

Will Wilcox’s hands shook so violently he worried he might whiff. This was February 2016, on the 10th tee at PGA West’s Stadium Course in California, his first hole of the CareerBuilder Challenge. Wilcox was coming off his best season as a professional. He ranked inside the top 150 in the world and had full PGA Tour status—the small triangle atop the sprawling pyramid of professional golf. And he felt worse than ever.

“Some guys reach the pinnacle and they work harder,” Wilcox, now 34, says. “I reached my pinnacle and it just made me nervous. It was not a good feeling.”

The situation on that tee box wasn’t particularly distressing in a vacuum; it was the culmination of a multi-year buildup of stress and anxiety. Born and raised in rural Alabama, Wilcox’s upbringing included multiple DUIs, a short stint in jail, getting kicked off the golf team at the University of Alabama-Birmingham and being rejected by the Navy due to his criminal record. He found refuge in the low-key confines of Clayton State University, where he finished his college career, and the now-defunct Hooters Tour, where he quickly emerged as a force.

"Some guys reach the pinnacle and they work harder. I reached my pinnacle and it just made me nervous. It was not a good feeling.”Will Wilcox

“I enjoyed the Hooters Tour. When I went up to the Korn Ferry Tour, I wasn’t ready. I didn’t want to go. I wanted to stay on the Hooters. They’re like, you’re exempt for the rest of the year. And in my head I’m like, but I don’t want to go up. I want to stay, wait. Can I start next year? I never asked that question, but I wasn’t ready for that step up. It was like, bam, I’m out there, and you’re playing with guys from all over the world. There are eagle eyes on you. It was not what I was expecting.”

With each next step on the road to the PGA TOur, Will Wilcox questioned whether he was truly ready, always feeling like he didn't belong.

Harry How

Despite the ambivalence toward his new surroundings, Wilcox’s golf continued to flourish. In 2013, he became the fourth player in Korn Ferry Tour history to shoot 59. He’d finish seventh on the money list to earn promotion to the PGA Tour, where the spotlight burns that much brighter.

He immediately felt like an outsider on the Big Tour—a chill, rail-thin Southerner rubbing shoulders with chiseled Europeans following strict nutrition programs. He did not enjoy the company of the vast majority of his peers. Wilcox remembers looking around a crowded driving range at an event and struggling to find a handful of players he’d invite to a barbecue. Here was a young, single man, traveling city to city, hotel room to hotel room, spending the four-ish hours time between golf shots thinking dark thoughts. He felt painfully alone and like everyone wanted a piece of him, all at once. There were shadowy characters from his hometown who suddenly felt entitled to the spoils of his success. Accusations of being “too big for his britches.” So many people to please.

“When I reached the height of my game, it just felt like the pressure of the world was on me,” he says. “I didn’t like that feeling, at all. More people pulling at my coattails. People were really on me. It led me down a path of self-medication, which is a fancy way of saying I was drinking too much. That works for a little bit, but it made the travel so much harder.”

He’s far from the only tour player who’s turned to the bottle in a futile attempt to numb his feelings. In 2019, Chris Kirk took a leave away from golf to address his alcohol abuse. In July, Grayson Murray took to Twitter to let some things off his chest.

“Playing the PGA Tour is awful for me,” Murray wrote. “I’ve struggled with injury’s (sic) the last 5 years, but those seem so minor to what I struggled with internal....I’m a fucking alcoholic that hates everything to do with the PGA Tour life.”

But PGA Tour life is, for so many weekend warriors and mini-tour grinders, the ideal. The man toiling in a factory to scrape together enough cash for rent would happily trade places with a struggling PGA Tour player. The PGA Tour players know this, and it contributes to a cognitive dissonance that adds guilt to an already gnarly cocktail of emotions.

(Update: The PGA Tour provided Golf Digest details of the mental-health services offered to its players. “The PGA Tour’s Health Plan provides mental well-being benefits for players and members of their household,” the tour’s statement read. “This assistance program is an international and domestic resource that introduces players in need to mental health specialists who can help address anxiety, depression or other mental health concerns.” The tour also noted that a player could be eligible for a medical exemption if a mental-health issue prevented the player from competing, and that most prescribed antidepressants are permitted under the tour’s anti-doping policy).

“That’s another thing that really bothered me is how selfish I sounded,” Wilcox says. “You could call it complaining. Some people have to punch that time card to feed their families. That bothered me. How dare I feel this way? And that makes it a lot worse. It makes you feel greedy and undeserving of what you’re doing.”

The problem with the “he’s rich and famous and plays golf for a living, I don’t feel bad for him,” viewpoint is it’s based on a false pretense: that being rich and famous and playing golf for a living somehow insulates you from loneliness, or homesickness, or depression. Just because Person B’s problems may be worse than Person A’s does not delegitimize Person A’s feelings.

Mardy Fish knows this first-hand. A former top-10 tennis player in the world, Fish recently opened up about his struggles with anxiety and depression in Netflix’s Untold: Breaking Point.

“When I was playing my best tennis, my stress didn’t come in the financial sense, of course,” Fish says. “It came in expectations. I tried so hard to get everything out of my playing ability. Everything I put in my body was on purpose. Everything I did on the course, off the course, away from tennis, was to do with my career and how to win tennis tournaments. So expectations from myself, from the media, from the press, were things that would weigh on me.”

Dr. Lardon concurs: “It doesn’t matter how rich you are—if you have a psychological condition, you might have every possible thing in the material world. A beautiful wife, a Mercedes. And meanwhile you can’t sleep. You’re anxious.”

So anxious, in Wilcox’s case, that he could not bring his driver back on that tee box. He eventually did—way too quickly. Snap-hook into the junk. It was then that he’d reached his breaking point. Alcohol wasn’t working. He needed help. After missing the cut, he flew home to South Florida and went straight to a psychiatrist, who prescribed medication to treat his panic disorder. It provided significant relief, and Wilcox continued playing professional golf for another five years without having to deal with crippling panic attacks. But a combination of injuries, a drop to the Korn Ferry Tour and a disdain for suitcase life prompted his retirement in July. He gives lessons to juniors now, sells golf clubs and fixes up cars with friends. And he doesn’t miss tour life.

“I enjoy the little things around here,” he says. “I love looking at the lake, having a camper that I paid for fully in cash. I’m liking sitting still. To be honest, I’m glad it’s over.”

Wilcox will tell you he didn’t love the grind; Erik van Rooyen does. The affable South African played collegiately at Minnesota before returning home to play the distinctly unglamorous Sunshine Tour. He clawed his way onto the European Tour then had the type of breakthrough week that catapults careers in February 2020, when he finished T-3 in the WGC-Mexico Championship. That finish allowed him to gain full PGA Tour status through non-member points for the 2020-21 season.

He was climbing the golf ladder steadily until he ran into a wall. Van Rooyen missed 10 of his first 20 cuts in his freshman campaign and sat 139th in the FedEx Cup standings. The only headlines he’d made were awful ones—he lost his temper in front of TV cameras in a humiliating episode at the PGA Championship, where he destroyed a tee marker and snapped his club, the remnants of which nearly sliced the leg of a fellow player’s caddie. Another missed cut, a public apology—it all began to wear on him.

“I spoke to a psychiatrist back home in South Africa because I was feeling like absolute balls,” van Rooyen, 31, says. “It was bleeding into my personal life. I was measuring myself as a human being based on my world ranking. That went through my mind. I spoke to a lot of people about how to separate Erik the Human Being from Erik the Golfer. Obviously, that’s a lot easier when things are going well, but even if I’m winning, I don’t want to be known just as a guy who wins golf tournaments. It was important for me to learn how to separate the two regardless of result. It was a bit of a journey.”

The solution?

Erik van Rooyen walks during a practice round prior to the 2021 PGA Championship.

Stacy Revere

“I started bringing my guitar on the road. It’s one of the things that my sports psychologist, Duncan McCarthy, talked about. When you get in your car and you're on the way to the hotel, it’s like, OK, it’s now time to spend time with Erik the Human. Erik the Golfer is now done with his day. I go spend time with my wife, my daughter or playing guitar.”

After broadening his identity beyond golf, van Rooyen’s golf took off. He won his first PGA Tour event at the Barracuda Championship, then rode a heater throughout the FedEx Cup playoffs to make the Tour Championship and guarantee a spot in all four majors in 2022. Van Rooyen learned a crucial aspect of successfully navigating the PGA Tour—having interests and passions and purpose outside it. It’s a huge reason why so many players travel with their families, or dive into bible study, or pour effort into their foundations, or bring their guitars with them on the road.

“It’s hard for these very focused individuals to look at every part of their lives and want to grow in those areas, because they’ve been trained to think of themselves as a golfer,” Sessinghaus says. “There are other puzzle pieces that you need to make you whole. There are many parts of them that make them who they are.”

Sessinghaus’ star student has internalized this message. Morikawa is frequently joined on the road by his girlfriend, Katherine Zhu, and while a number of his peers travel with a chef and hardly ever leave their rental home, the 24-year-old prefers a little more adventure—and prefers might not be a strong enough word. Even Morikawa, a golden child of sorts, the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent of professional golfers, with two major championships on his mantle, needs to get away.

“She’s helped me so much,” Morikawa says of Zhu. “Especially out on tour, it’s a very lonely life. Everyone will tell you, at parts of their career, they’ve been lonely. Having her travel with me, we’ve been able to explore new cities, have good dinners. I’ve just been able to relax, not to stress about the next day so much. I think that’s how some of the best players out there that have families, kids traveling with them, are able to flip the switch. On the golf course, it’s golf; it’s business. Off the course, they don’t tire themselves out. Without her, I’d be so focused on golf 24-7, getting antsy about the next round, stuff like that. You can never do that.”

The key is finding a rhythm and techniques that work for the individual. A growing number of tour players have turned to breathwork, meditation and mindfulness practices, including journaling. Before the final round of the Genesis Invitational in February, which he went on to win, Max Homa sat in his car and listed all the things in his life he’s grateful for. When he became frustrated with a shot, he thought not of the poor swing he made or the brutal lie in his future, but of the unconditional love from his dog. Of his wife. Of all the wonderful friends surrounding him. Max the Golfer may have hit a poor shot, but Max the Man has so much to be thankful for. And while spending copious amounts of time on social media doesn’t seem to affect Homa, Jordan Spieth had to cut it from his life to preserve sanity during his slump.

“I do a really good job of blocking out the noise,” Spieth said after winning the Valero Texas Open, which ended a four-year winning drought that he was reminded of ad nauseum. “The only noise I hear is really just in the interview room. I don't see anything, don't read anything. I mean that. I started doing it kind of in the middle of 2018, and it's been really good for me. I haven't missed it.”

'There are some super-high profile golfers, and ones in the past, that are on medication. I wish more would come out and just be honest about what’s happening.'Dr. Michael Lardon

But meditating and blocking Twitter only go so far if there is a chemical imbalance in the brain. A growing number of tour players are seeking professional help not only from the types of sports psychologists that have hung around the tour for decades, but from medical doctors like Dr. Lardon, who can diagnose psychiatric conditions and prescribe medication to treat them.

“There’s a number on the men’s tour that I help,” says Dr. Lardon, “but we never talk about it. There are some super-high-profile golfers, and ones in the past, that are on medication. And what does the media say? They say what the player’s PR person or agent says. I hurt my back. I got dizzy. I wish more would come out and just be honest about what’s happening, but it’s not my place.”

If Dr. Lardon’s experience is any indication, there remains a stigma around psychotropic medication. Perhaps players, even subconsciously, view it as an admission of defeat—that they’re not strong enough to handle being a professional athlete on their own. They view their inability to perform in high-pressure moments as a personal shortcoming, as being “unclutch,” rather than the result of a chemical condition. They’ve been told their curious pre-game rituals are “superstitions” rather than a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder. There’s a worry of portraying weakness, or how it might be received by their peers or the public. Part of the issue, Dr. Lardon says, is the lack of tangible detection methods.

“If you break your leg, the doctor brings you down and shows you the X-ray. Here’s your leg, it’s broken, tibia fractured. He tells you they need to operate. You don’t have any issue with it, you agree with the doctor. The apparatus of perception is intact. But when you have a clinical depression, your apparatus of perception is broken. It’s impaired. It’s very difficult to antperceive yourself accurately. Am I depressed? Am I a wimp? Do I believe in depression? It’s invisible. It’s not like showing you an X-ray or the results of a blood test.”

Modern innovation could make the invisible, visible. Dr. Lardon sits on a board of a company that is developing technology that analyzes gene expression to identify protein markers for depression, suicidal thoughts and other internal conditions.

“We’re very close to an objective measure,” he says. “This will be a breakthrough.”

Until then, potential patients must rely on doctor’s advice and word-of-mouth. It’s one of the reasons Mardy Fish wanted to come forward with his journey: to tell other male athletes the tale of a fellow male athlete who had an injury of the brain, sought treatment for it, and returned healthier and happier.

“I’ve had thousands—not hundreds—thousands of DMs on my Twitter since Untold came out. Not every one of those people has a normal job. There’s a lot of athletes that have written me and said, ‘Hey, thanks for doing this, I have XYZ and it really resonated with me.’ You’d be shocked at how many athletes that you and I have heard of and haven’t heard of.

“I felt comfortable with it because it helped me. It made me feel better. And then after I got better and got to a point where I got really comfortable talking about it, I wanted to be a success story for someone.”

Will Wilcox wishes he had access to that type of success story during his playing days—a reassurance that he wasn’t the only one feeling overwhelmed by his reality.

“Most of the guys keep everything close to their chest. It’s a very private game. They’ve got their team, and you’re not getting in that bubble. But it would’ve been cool to have—they have Tour Life, where you talk about God and religion, but it’d be really cool if you could have a group where you could talk about the anxieties. What a cool idea that would be, to have that available to players. A lot more guys would show up than you’d expect.

Matthew Wolff knows he is not cured, for such an elixir does not exist. (Wolff, through a representative, declined to be interviewed for this story.) Mental health is an ongoing journey. There is no endpoint. He also knows he has greatly improved from rock bottom, when he didn’t want to get out of bed for fear of failing in front of everybody.

Wolff returned to competition at June’s U.S. Open and posted his first top-10 since his hiatus with a runner-up finish at the Shriners Children’s Open earlier this month. But even before that good week on the golf course, Wolff began having good weeks off the golf course. Because Matt Wolff the golfer does not define Matt Wolff the person.

“I know the scores might not be better,” Wolff said in August before The Northern Trust, “but I'm feeling better. I'm happier. And I'll look to keep on being happy.”