the arnies

Arnie Award winner Rory McIlroy carries a special burden Palmer knew all too well

The greatest golfers have always given back. Automatically through the permanence of their records. Proactively by sharing their stories and accumulated wisdom. Munificently through philanthropy that leaves the game and the world better. Historically, no group in golf has had more to give, or given more, than the players in its pantheon, from Harry Vardon to Tiger Woods.

The current professional game, however, seems preoccupied with taking, leaving its precariously perched administrators nothing but headaches. Will playing records lose all context? Will golf’s top names stop replacing their metaphorical divots? Will the Pantheon close?

Sorry, doom-loop moment. Actually, professional golf remains full of givers; they’ve just been drowned out by all the hammering on the framework agreement. But the most generous among them has risen above the noise: Rory McIlroy.

The Northern Irishman’s game is a gift, of course—not quite in the pantheon but at age 34 with a shot. More important to the subject at hand is that no matter how he plays, McIlroy stands out for having the extra dimension. Despite the demands and often disorienting forces of fame, not to mention the psychic pummeling meted out by a sport that has caused many past stars to become more remote, McIlroy remains endearingly drawn to people. Whether in casual interactions or trying to save professional golf, he continues to easily and purposefully give of himself.

This happens to be precisely what made Arnold Palmer golf’s greatest giver. We found it appropriate, then, in a moment when such qualities are more needed than ever, that Rory McIlroy receive the 2024 Arnie Award, Golf Digest’s highest honor for golfers who give back.

“I’ve told Rory many times that he’s today’s Arnold Palmer,” says Brad Faxon, who was befriended by Palmer as a PGA Tour rookie in 1984 and who has been McIlroy’s putting coach since 2018. “Like Arnold, he has this innate feel for others, an ability to read people and make them comfortable. When Rory meets someone, he looks them right in the eye, asks them questions about themselves, listens to the answers and breaks through. If he has to say no, he’s always polite. He’s the same in a high-stakes setting—clear values, speaks from the heart, sees other points of view, easy to trust. Just by being himself, he has followed Arnold’s example and protected the game at a very difficult time.”

Faxon, of course, was referring to the ongoing fracture in the professional game caused by Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund offering huge sums to PGA Tour and DP World Tour players to join the Greg Norman-led LIV Tour. Soon after McIlroy became a player director on the PGA Tour Policy Board in 2022, players jumping to LIV brought home the reality that the tour was facing an existential threat. McIlroy’s sincere, clearly articulated arguments for a unified front soon made him the tour’s favorite front man. His opponents issued verbal counterattacks, and emotions ran high, but McIlroy’s willingness to stand in a harsh spotlight and issue his urgent but measured message was admired, especially as he continued to win tournaments and once again ascend to No. 1 in the world.

“Legacy, reputation, at the end of the day that’s all you have,” McIlroy said at the 2022 U.S. Open. “You strip everything away, and you’re left with how you made people feel and what people thought of you. That is important to me.”

Palmer held to the same perspective in 1994 when Greg Norman was attempting to recruit the highest-ranked players to launch the World Golf Tour with 40-man fields and big purses. According to players present in a closed-door meeting during the Shark Shootout at Sherwood Country Club, Palmer recounted how he and Jack Nicklaus were presented with an opportunity in the late 1960s to separate from the PGA Tour and make much more money, but “both of us decided we’d do what was best for the game.” All the players Norman had counted on to jump followed Palmer’s lead instead and stayed with the tour.

Such a quick resolution was never in the cards for this current moment, but McIlroy took on the thankless task of trying to balance the differing priorities of stars and journeymen as the tour transformed its schedule to include more limited-field events with lucrative purses designed to keep big names happy as a counter to offers from LIV. Woods said that such interaction was key to McIlroy being “a true leader out here on tour. Everyone respects him, and they respect him not just because of his ball-striking, his driving, but the person he is.”

With similar antipathy toward the threat of LIV, Woods and McIlroy became perceived as a tag team, particularly after they led the crucial closed meeting in Delaware in August 2022 that included about a dozen top players. Woods and McIlroy also became business partners in Tomorrow’s Golf League (TGL), the virtual, under-a-dome competition set to launch in January 2025. Though McIlroy actually finished ahead of Woods in the PGA Tour’s 2023 Player Impact Program—which measures media interest—after Woods was first the previous two years, McIlroy invariably defers to Woods. “It’s pretty apparent that whenever we all get in the room, there’s an alpha in there, and it’s not me,” McIlroy says. “He is the hero that we’ve all looked up to. His voice carries further than anyone else’s in the game of golf.”

Growing up just outside of Belfast, McIlroy knew every detail of Woods’ rocketing accomplishments. After winning the Open Championship and the PGA Championship in 2014 put him on the Tiger-Jack track of four majors by age 25, McIlroy seemed to be channeling Tiger, aiming to become insatiable about winning and relentless about his fitness. He proudly spoke of having developed a ruthless streak.

But part of him must have known he was attempting to overcompensate for his own nature. “I’ve no real ambition to be the best at anything else,” he confessed in the same Golf Digest interview. “If we’re playing a game of cards or a game of pool, whatever it is, I’d happily let someone win just to keep them happy.” He added that as a teenage prodigy, “I felt it was a very selfish thing to be a winner … I guess it just took me a while to get comfortable with that, just because of the personality I have. I realized that if I want to succeed in golf, which I do, I need to have it. What helped was realizing how people like winners, how people gravitate to them. If other people are happy with me winning, then why can I not be?”

This question would not occur to Tiger. Arnie, however, would have understood the softer side. When interviewer Graham Bensinger in 2015 asked Palmer his impressions of McIlroy, his answer—“He’s a nice guy”—included a nod that confidently conveyed expertise on the subject. The comment also brought back how disarmingly nice Palmer could be. Then-PGA Tour commissioner Tim Finchem described it well in his eulogy at Palmer’s memorial service. “Arnold had that other thing,” Finchem said, “the incredible ability to make you feel good—not just about him—but about yourself. He took energy from that and then turned around and gave it right back.”

McIlroy felt the chemistry when the two shared a long dinner at the 2015 Arnold Palmer Invitational. The next day, when the tournament host saw McIlroy and casually asked if there was anything he could do for him, Rory executed Finchem’s boomerang perfectly. “No, Mr. Palmer,” he said, “thanks to you I have everything I could ever want in my life.”

McIlroy and Palmer at Bay Hill in 2015.

If McIlroy hasn’t yet attained everything competitively, it could be because he also shares a vulnerability that plagued Palmer. Though he gained fame in his prime for his “charges”— come-from-behind victories fueled by a joyful confidence and his Army’s frenzy—by 1965 he had fallen into a prolonged slump. “I suddenly got to worrying about disappointing everyone,” Palmer told Golf Digest’s Tom Callahan. “For the first time in my life, I guess I was afraid.” The next year he blew a seven-stroke lead with nine holes to play at The Olympic Club to lose what should have been, at age 36, a redemptive U.S. Open victory. As crushed as Palmer was by the defeat, he still noted in his autobiography that “I really felt worse for my fans.”

The desire to please others can divert focus and add a layer of pressure to winning. How much of a role that trait has played in McIlroy’s major-less streak since 2014 is up to conjecture, but the questioning deepened with his recent close calls in majors—the 2022 Open at St. Andrews where he led by two with eight to play before finishing third, and last year’s U.S. Open at Los Angeles Country Club, where he lost by one to Wyndham Clark.

Such setbacks have caused his career clock to tick louder, and it seems McIlroy is allowing the pendulum within to swing more toward what he used to consider selfishness. Though he maintained a high level of play throughout 2023, he won only once—at the Genesis Scottish Open in July—and began to feel worn down by his role on the policy board. He was also left dispirited by not having been consulted before the surprise June 6 announcement of the “framework” agreement between the PGA Tour and the PIF. At a press conference the day after, McIlroy said that after many months of “putting myself out there,” he felt like a “sacrificial lamb.” He also used the occasion to vent at the entity whose disruption had taken so much time and attention away from his game and his family—wife, Erica, and their 2-year-old daughter, Poppy. “I hate LIV,” he said. “Like, I hate LIV. I hope it goes away.”

In November, McIlroy resigned as a player director. “I just didn’t feel like I could commit the time and energy into doing that,” he says. “Something had to give, and I felt like it was the right time to step off.” Says Faxon, who served four three-year terms on the board during his career, “Rory’s two years were like 10 normal ones.”

McIlroy’s explanation included the words, “as I try to get ramped up for Augusta.” The upcoming Masters will mark the 10th time a victory would give him the career Grand Slam.

That’s Pantheon stuff. If our Arnie Award recipient has any lingering misgivings about taking a step back from the front lines of the battle for professional golf’s future and a step forward as a golfer, a simple truth should clear his mind.

If he wins the Masters, he’ll be giving back like never before.

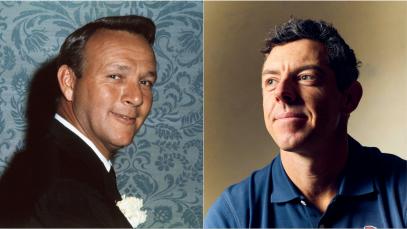

TWO OF A KIND

For our February cover, we asked Rory McIlroy to re-create this photograph of Arnold Palmer from the Golf Digest Archive. Rory loved the image and studied it to get the body positioning just right. During our shoot, McIlroy was gracious to the entire crew, introduced himself, shook each person’s hand and thanked everyone on the way out—just like Arnie would have done.

(Golf Digest+ members get access to the complete Golf Digest Archive dating back to 1950. Sign up here.)