News

U.S. Open 2017: Why exactly are there amateurs here? An explainer

ERIN, Wis. -- Casual or new golf fans might wonder why 14 players have an "a" preceding their name on the U.S. Open leader board. This stands for "amateur." No matter how well they finish, these guys collect no prize money. Zip, zero, nada. Before you scream at this apparent injustice, consider that golf is the only sport that truly and regularly offers this peculiar opportunity. That is, to compete alongside the world's best while still in the developmental stage of one's athletic career.

The best college quarterbacks don't get to take snaps in the Super Bowl. The best in college hoops won't see what it's like to play guard in a NBA Championship until (rather if) they make it there as pros themselves. College hockey players won't experience how fast guys skate in the Stanley Cup, and on down the line.

Why? It all dates back to 19th century England and a society obsessed with class. In golf, but also sports like rowing, "amateurism" was a way for rich people to ensure they would spend the day with their own kind. If you needed the prospect of winning a little cash to justify taking the day off from work to play a game, well, you weren't invited to muck around with nobles. And besides, those muscle-knotted brutes who worked unloading freight at the docks might well win, and really spoil the fun.

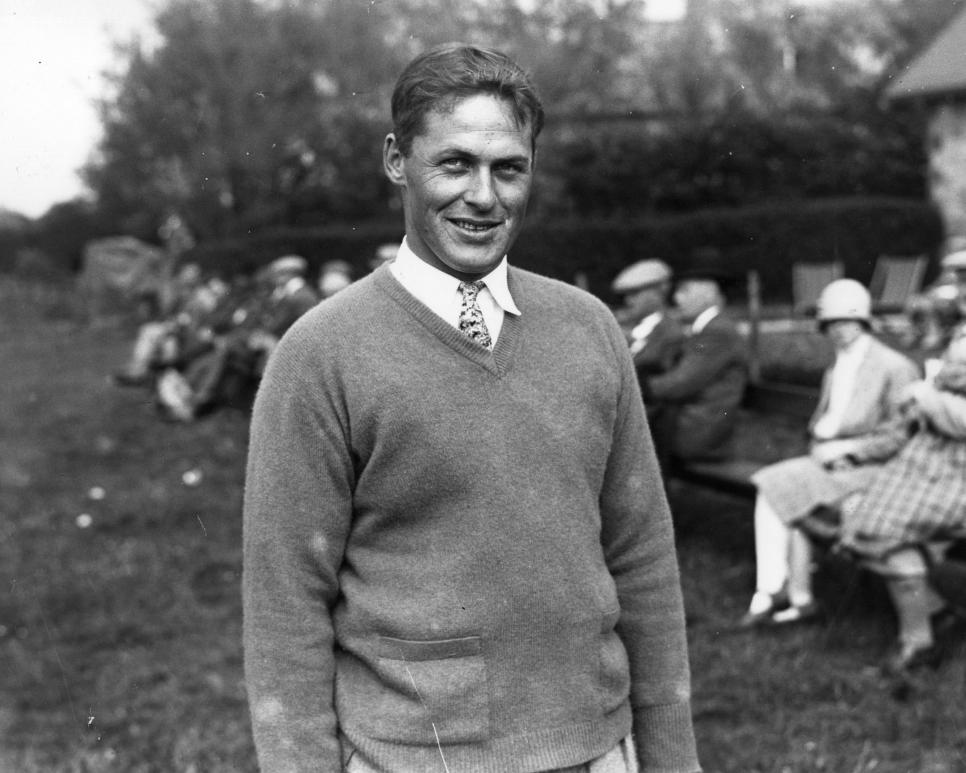

Getty Images

Caddies, greenkeepers and anyone who profited from golf had their separate "pro" tournaments. These were the first "opens," in that they were open to anyone, and often it was here that the higher standard of play was found.

Of course, the story of 20th century sports is how amateurism was overtaken by the big business and mass entertainment of watching people who played for a living. A transition that happened at different speeds. It wasn't until 1968 that our national championship in tennis became an event with prize money. Technically, tennis' U.S. Open is still open to amateurs, but the gulf between the college and pro level in men's tennis is so wide that amateurs hardly ever qualify. It was a sensational story in 2016 when 17-year-old CiCi Bellis reached the third round of the women's draw and forfeited $140,000 in winnings.

Also, tennis and other individual sports aren't as hung up on amateurism as golf. College tennis players often make paychecks as instructors during the summer, but a college golfer doing the same would violate his amateur status, and thus ability to compete in club and amateur events. Considering the amount of financial support the top collegiate, high-school and even middle-school athletes get these days, across all sports, it's questionable what amateurism even means anymore. The old joke used to be the amateur golfer was the only one who washed his ball on the first tee. But nowadays companies seed free gear far and deep.

The last golfer to win the U.S. Amateur and not later turn pro was 1975 champ Fred Ridley. But now the potential money is too large for a very talented player to not to give it a try. And if you fail, it's easy to apply and get reinstated as an amateur by sitting out from competition for a year or so. Most importantly, being a pro is cool. The stigma of the 19th century has totally flipped.

The debate on amateurism is old and dry, and will continue to be so for years. But what's new at this year's U.S. Open is that more more young players will get to play alongside the world's best. Or at least practice. That's because the USGA, for the first time ever at Erin Hills, is allowing the other "a" (alternates) to play practice rounds. It used to be the handful of players waiting around for someone to get food poisoning or break a wrist only had access to the driving range and the short game practice area. So if they were lucky enough to get in at the last minute, they would play the course cold.

Brandon Wu, a sophomore at Stanford University who is both an amateur and an alternate, played practice nines with Sergio Garcia and Justin Rose yesterday. "It's quite the experience. I think I want to turn pro, and playing out here has let me see so much," Wu said. "They're so meticulous with how they prepare. My goal with practice rounds is usually just to know the course, but these guys have the imagination to really picture the shots they're going to have." Wu has seen that his ball-striking can hang, but every once in a while "they hit a shot that's just like, wow."

Whether he gets in the field or not, hitting those shots with money on the line is an experience Wu will wait to have.