News

The story of Moe Norman, golf’s troubled genius

This is a new series on the 70th anniversary of Golf Digest commemorating the best literature we’ve ever published. Each entry includes an introduction that celebrates the author or puts in context the story. Catch up on earlier installments.

David Owen is a writer’s writer. He married a writer and has a daughter and son who are writers. Having graduated from Harvard with a degree in English, he wrote his first book after going back to high school as an undercover student. He has written for all the writers’ magazines: Harper’s, The Atlantic, The New Yorker (since 1991), and Golf Digest (since 1995). He’s authored a shelf of books, many good ones about golf and home remodeling. One of my favorites is called The First National Bank of Dad. He’s also known for taking excessively dull subjects, like concrete and water, and writing fascinatingly about them in magnum opuses for The New Yorker.

His subject was far from dull in this piece for Golf Digest that was published 25 years ago. Moe Norman was an obscure Canadian pro who had become a cult figure among serious golfers. Long past his prime, Pipeline Moe could still hit the ball with incredible accuracy that brought to mind perhaps only Ben Hogan and Lee Trevino in the game’s history. But Moe was equally known for repeating everything he said twice in rapid succession—and for being, well, a bit odd. Though the diagnosis of autism had been written about since 1927, it became more public with the Dustin Hoffman character Raymond in the 1988 movie, “Rain Man.” Moe was golf’s Rain Man, and Owen wrote a sympathetic, celebratory cover story that made him a sensation at age 66.

“Shortly after the article came out,” Owen says, “I got to play a round with Norman and his friends Gus Maue and Todd Graves (who calls himself Little Moe and teaches Norman’s unorthodox swing) at Royal Oak Resort and Golf Club, in Titusville, Florida. Royal Oak has long since gone out of business, but in 1995 it was a favorite winter hangout of the Canadian PGA. The first hole was a 400-yard par 4, dogleg to the right. Maue, Graves and I hit tee shots up the middle, and then Norman hit his over a row of trees to the right, toward a lake that ran the length of the hole. I thought, Hmmm—this is one of the greatest ball-strikers of all time? But it turned out that Norman always played the hole that way. There was a strip of grass, maybe 10 yards wide, between the trees and the water, and from there he had an easy 9-iron to the green, while those of us in the fairway needed 4-irons or 5-irons.”

I remember Owen became a disciple of the Moe method of gripping and swinging the club for several years afterward. David was late to taking up the game, but he turned into a ferociously avid single-figure handicapper, as he remains today with a more conventional technique. Anyone who ever witnessed Norman hit a ball could not help but be changed by the experience. Moe died in 2004, but left many followers who still teach his method. —Jerry Tarde

Sam Snead played an exhibition match with Ed (Porky) Oliver and Moe Norman in Toronto in 1960. On one par-4 hole, a creek crossed the fairway about 240 yards from the tee. Norman, a Canadian pro who lived in the area, reached for his driver.

“This is a lay-up hole, Moe,” Snead warned him. “You can’t clear the creek with a driver.”

“Not trying to,” Norman said. “I’m playing for the bridge.”

Snead’s and Oliver’s tee shots ended up safely on the near side of the water. Norman’s drive landed short—and rolled over the bridge to the other side.

Every golfer hits a lucky shot from time to time. But Norman, who recently turned 66, has hit so many lucky shots during the last half-century that you begin to search for a different adjective.

At an exhibition once, Norman hit 1,540 drives in a little under seven hours. None was shorter than 225 yards, and all landed inside a marked 30-yard-wide landing zone.

Consider Norman’s experience during a practice round before the 1971 Canadian Open: A week earlier, at the Quebec Open, he had come to the final hole with a one-stroke lead but had four-putted the final green to finish second. “Any four-putts today?” a reporter asked Norman as he came to the tee of a 233-yard par 3. Norman teed up a ball in silence and hit it straight at the pin. He watched the ball’s flight a moment, then turned to the reporter and said, “Not putting today.” The ball landed on the front of the green and rolled into the cup.

Norman is mostly unknown to American golf fans, but he has long been a nearly mythical figure among tour professionals. Paul Azinger first saw him hit balls on a range in Florida 15 years ago when Azinger was a college player.

“He started ripping these drivers right off the ground at the 250-yard marker, and he never hit one more than 10 yards to either side of it, and he hit at least 50,” Azinger told Tim O’Connor, a Canadian writer who wrote the biography of Norman, The Feeling of Greatness. “It was an incredible sight. When he hit irons, he was calling how many times you would see it bounce after he hit it—sometimes before he hit it—and he’d do it. It was unbelievable.”

At an exhibition once, Norman hit 1,540 drives in a little under seven hours. None was shorter than 225 yards, and all landed inside a marked 30-yard-wide landing zone.

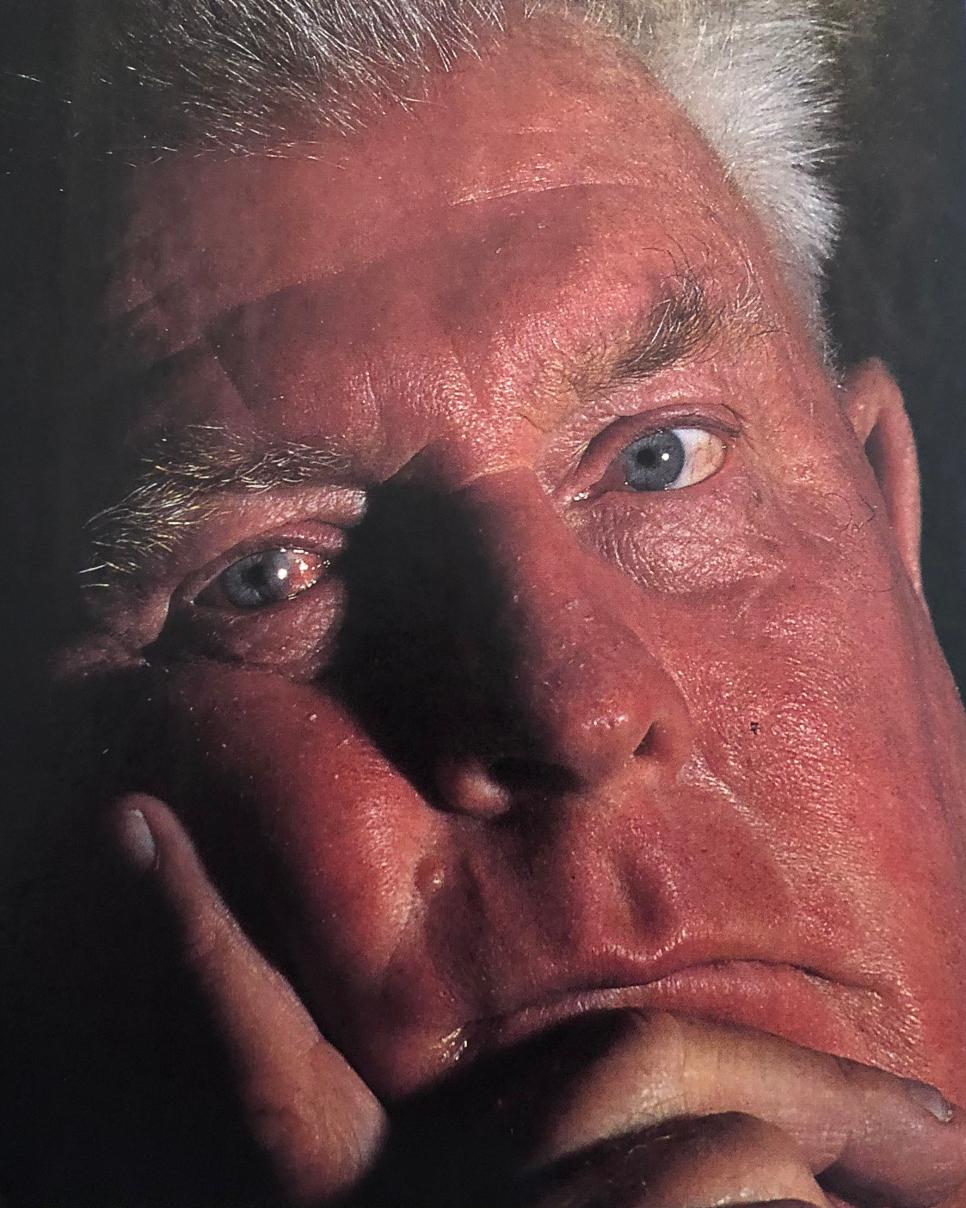

Norman doesn’t look like a legend. His graying red hair stands more or less straight up, giving him a look of perpetual surprise. He wears long-sleeved shirts in even the hottest weather, and he buttons them up to his chin. His pants don’t fit very well; during his playing days, they often gave out just south of mid-shin.

He likes bright colors and enjoys mixing stripes and plaids. His teeth would give an orthodontist pause. A huge proportion of his daily caloric intake is in the form of Coca-Cola. His voice is high, he speaks rapidly and often repeats himself, especially when he’s nervous.

But Iron Byron doesn’t have much star quality, either. Professional golfers’ high regard for Norman has always been based primarily on his phenomenal ball-striking. Lee Trevino ranks Norman with the game’s very best, including Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson.

Ken Venturi agrees: “Because Moe is kind of eccentric, he never got the credit he deserved or played the kind of golf he was capable of. You had to ignore the way he looked over the ball and judge his ball-striking. Hogan, Snead, Nelson—they all look esthetic. Moe looked very awkward. But he could do anything. He is one of the premier ball-strikers I have ever seen. Hell, I’d give Moe three strokes a side just to watch him hit the golf ball.”

In his heyday, Norman translated his ball-striking genius into an impressive competitive record. In the late ’50s, he won dozens of amateur tournaments in Canada, including the Canadian Amateur two years in a row. His best year as a pro was 1966, when he won five of the 12 Canadian tournaments he entered, came in second in five, finished no lower than fifth, and won the CPGA scoring average title by 2½ strokes, with 69.8.

Beginning in 1979, when Norman turned 50, he won seven consecutive Canadian PGA senior championships, tied for fifth in the eighth, and won the ninth by eight strokes. He has set more than 30 course records, including three with scores of 59 and four with scores of 61. (He shot his most recent 59 four years ago, at age 62.) Last August, the Royal Canadian Golf Association inducted him into the Canadian Golf Hall of Fame.

These are considerable accomplishments. Still, there are conspicuous gaps. He played almost exclusively in Canada and made only a brief attempt, in 1959, to play on the U.S. tour. If Norman is one of the greatest ball-strikers in history, why doesn’t he also have one of the greatest records?

The reasons are complex. One of them, paradoxically, has to do with the very foundation of his game: his golf swing. Simply put, Moe Norman’s swing doesn’t look like the ones you see on TV. He grips the club in his palms rather than his fingers, stands far from the ball with his legs spread wide; he soles the club as much as a foot behind the ball, squeezes the grip almost unbelievably hard with his left hand, takes the club back scarcely past the level of his right shoulder. Nearly every time Norman teed it up in a tournament, he had to endure the laughter of spectators. He was often viewed as an amusing sideshow, not as the main event, and he reinforced his reputation as a clown by playing to the galleries.

Norman is different in other ways as well. His personality is eccentric, to say the least. He is uncomfortable with strangers and has difficulty making eye contact with people he doesn’t know. He does not like to be touched. He has never married or had a serious relationship with another person, and he has essentially no interests outside of golf. Despite his accomplishments, he has always been plagued by a fear that he doesn’t measure up.

That Norman managed any sort of competitive career can begin to seem astonishing. His upbringing was modest in the extreme and did little to prepare him for the U.S. tour, where he felt conspicuous and inadequate next to famous players who dressed better and had more money than he did. He spent much of his 40-year competitive career in obscurity and poverty. He sometimes carried his bag in tournaments because he couldn’t afford a caddie. When he had money, he kept it in a wad in his front pocket. He spent many winters—including the one before the 1956 Masters, to which he had been invited as the reigning Canadian Amateur champion—setting pins in a bowling alley for a few cents a line. As recently as eight years ago, he was so broke that only the last-minute intervention of friends prevented his car from being repossessed. At that time, he was eking out a living by giving golf clinics for a couple of hundred dollars apiece. Even today, Norman lives in a $400-a-month motel room and has no telephone. He keeps his clothes in the back seat of his car.

“When was the last time you hit a bad shot, Moe?” I asked him. “Thirty years ago,” he said as he bent over to tee up another.

Norman might be destitute and forgotten were it not for the efforts over the years of a few close friends. Among those friends are Gus and Audrey Maue. Gus Maue has known Norman for more than 40 years, and for a time was the pro at a golf club where Norman had caddied as a boy. Today, Maue owns Foxwood Golf Club, in Baden, Ontario, where Norman spends most of his days during the warm months. (He spends his winters in Florida, where he plays at a golf club owned by the Canadian PGA). In 1987, the Maues conducted a golf tournament at Foxwood, which raised $25,000 for Norman and put him back on his feet.

For Audrey Maue, the key to understanding Norman came years later, in a movie theater. “We went to see ‘Rain Man,’ ” she said, “and suddenly it came to me: that’s Moe. It just seemed like a light was turned on. I had always known that Moe was different, and I had known a little about autism, but I had never thought about it in connection with Moe. I don’t know that he’s ever seen a doctor, about that or anything else, but everyone who knows him who saw the movie felt the very same way.

“Most people don’t understand where Moe’s coming from or why he is like he is. Life has always been a struggle for him. Just to be around people, period, made him feel uncomfortable. What he accomplished, he accomplished on his own.”

Effortless perfection

When you first see Moe Norman hit a golf ball you wonder, Why on earth does he swing the club that way? After you have watched him hit half a dozen 250-yard drives out of a divot, though, you begin to wonder, Why on earth don’t I?

On the practice tee at Foxwood Golf Club not long ago, Norman warmed up with a pitching wedge, although “warming up” doesn’t really describe any part of Norman’s practice routine. The first shot was perfect, the second shot was identical to the first, the third to the second, and so on. Then he switched to his 4-iron. His swing—for all appearances, a nearly effortless half-swing—was the same with the 4-iron as it had been with the wedge. The shots came one after another, just three or four seconds apart.

“How far you hitting those?” a spectator asked. “One-eighty,” Norman said. Every shot was within a few degrees of dead straight, despite a stiff crosswind, unless he announced ahead of time that he was going to hit a draw or a fade. The divots were identical (surreally rectangular scrapes that Norman calls “bacon strips”).

Norman switched to his driver. Once again, the swing was the same. If you watched only his arms and hand, you wouldn’t know that he wasn’t still swinging his wedge. After hitting one ball, he would watch it a moment, then bend over and place another on the tee—and I mean place it. The tee never came out of the ground. It didn’t move a millimeter.

“I hit balls, not tees,” he explained. On a driving range once, he hit 131 drives in a row from the same tee without having to straighten or adjust it. In tournaments, he sometimes entertained galleries by hitting drives from the mouth of the bottle of Coke he had just been drinking.

“When was the last time you hit a bad shot, Moe?” I asked him.

“Thirty years ago,” he said as he bent over to tee up another.

After he had been hitting drives awhile, a friend of his asked if he could try. The friend took Norman’s driver and placed a ball on Norman’s tee. The shot wasn’t too bad, but the tee came out of the ground and tumbled into the long grass 20 feet ahead.

“Oh, dear, I loved that tee,” Norman said wistfully. “I had it for seven years.”

Before Norman’s demonstration on the practice tee, he and I had spent some time together in Foxwood’s unpretentious dining room. It was there, about a month before, that he had been inducted into the Canadian Golf Hall of Fame. The audience at Norman’s induction was limited mostly to friends. At his request, the dinner was served family style.

As we talked, Norman held a putter and fiddled with his grip, or rolled a golf ball in his palm. He often finds it easier to be with children than with adults, and if a child is present he will sometimes pull a ball from his pocket and start an impromptu game of catch. I had been told that it might be hard to get him to talk, but that once he had started, it might be hard to get him to stop. He didn’t look me in the eye at first, but gradually he seemed to relax. Bit by bit, with numerous digressions—all of them related to golf—he told me about his life.

“It’s tough to do things when you’re broke,” he said. “Hitchhiking to tournaments, sleeping on park benches, sleeping in bunkers. I slept in bunkers all over Canada. You name it. I’d go and shoot 61 or 65, win the tournament, then hitchhike back on the highway with my TV set or whatever my first prize was, soaking wet. Couldn’t afford an umbrella then. Sometimes I had to put my golf bag over my head. Nobody would come to my rescue, not back then. This was back in the early ’50s. I was born in ’29.”

Norman grew up in a small house in a working-class neighborhood in Kitchener, an industrial city about 1½ blocks from a Uniroyal Tire factory. The sky was often black, the air smelled of burning rubber. Money was very tight.

Norman’s grade-school years were difficult. He had trouble getting along with other children and with other members of his family. He struggled in all subjects at school, except math, at which he was a prodigy. He also had a phenomenal memory. Today, he can recite the yardage of virtually every golf hole he has ever played, and he remembers every golf shot from every tournament that meant anything to him. He has a reputation as a deadly cribbage player because he remembers all the cards.

When Norman was a child, other children teased him remorselessly over his academic difficulties, his shyness, his big ears, his high voice and his tendency to repeat himself.

An expert, quoted in O’Connor’s book, speculates that Norman’s speech and personality quirks, even his unusual mathematical ability, may have arisen not from the mild autism that Audrey Maue suspects but from untreated head injuries he may have suffered in a sledding accident when he was 5. In that accident, he was dragged under a car a long distance, and he says he remembers seeing a tire roll over the side of his face. His parents could not afford to take him to the hospital, and his mother worried for the rest of her life that the accident had made a permanent change in her son’s personality. Whatever the reason, Norman’s childhood was mostly lonely. He found refuge in sports, and especially in golf, which he pursued with a devotion verging on mania.

Norman’s first golf club was a tree branch he and his older brother used to knock balls around their yard, his second was a hockey stick. At the age of 12, he began caddieing at a local club called Westmount. He bought his first real golf club, an old 5-iron, from a member who let him pay it off at 10 cents a week. “Oh, I was as happy as a pig in s---,” he told me. “I had a steel-shafted club.” Norman was left-handed, but the member was right-handed so he switched.

Norman practiced in his family’s tiny backyard by hitting balls against a neighbor’s garage. He rapidly developed a local reputation as a golf terrorist. When he would break a neighbor’s window—as he did 11 times in two years, usually because he was aiming at one—he would shout, “Bull’s-eye!” He built his golf game against enormous odds. The other members of his family made fun of him for playing what they viewed as an effeminate game and called him a sissy at the dinner table.

Norman told me: “My father used to say, ‘Come on, play a man’s game. Play hockey or baseball.’ I said, ‘No, Dad, I’m too light.’ I was a little skinny kid then, wasn’t over 130 pounds. I couldn’t play any other sport and be good at it, so I kept playing golf. But my father wouldn’t let me bring my clubs into the house. I had to hide them under the front porch.”

When he wasn’t aiming at the neighbor’s windows, Norman practiced in a field at a nearby public course. When I referred to this field as a driving range, Norman laughed. “Nobody had ranges then,” he said. “It was only a field, maybe 200 yards long. I had to wait till there was nobody playing to hit my driver. And the grass was tall. We had to use our irons to cut the grass down to fairway height, in a little square, and hit our balls from that.”

Norman carried his cherished collection of battered golf balls in an old canvas bowling bag. After he had hit them all, he would drop the bag among them and chip into it. Fear of losing his balls in the tall grass increased his desire to hit straight shots. He often hit until his hands were bleeding. When the blood made his grips slippery, he wiped his hands on his golf towel and pants, and kept hitting until it was too dark to see. When he got home, he looked as though he had spent the day slaughtering chickens.

Norman assembled his swing by feel, with a few clues gleaned from photographs in newspapers and magazines, and occasional encouragement from a kindly local pro. His progress was not immediate; he didn’t break 100 until he was 16. But gradually his golf game fell into place. By the time he was 19, he felt he had his swing “trapped.” From that point forward, he says, “I knew I could hit a golf ball where I wanted it to go for the rest of my life.”

Uninvited, apologetic, fast

The first significant step in Norman’s competitive career came in 1949, at the St. Thomas Golf and Country Club, a one-day amateur event later known as the Early Bird. He had not been invited. He showed up the day of the tournament and was given an empty slot. He was wearing sneakers. He had just seven clubs and carried them in a bag that was falling apart. Against a field that included several of Ontario’s amateur stars, he shot 67 and won by two strokes. Too shy to attend the awards dinner, he slipped away after finishing his round. A friend had to make apologies and bring him his prize.

Norman wasn’t like the other golfers in the tournaments he played. For one thing, he played fast. He would sometimes lie down and pretend to sleep in the fairway, waiting for slower players to hit. “I always thought the day was going to come when I’d get penalized two strokes for playing too fast,” he told me. “They had a meeting about it at one tournament. They said that people were complaining because they had taken off work to come to the tournament, and I was four under after five holes and they hadn’t seen me hit a shot. They said, ‘Please don’t walk so abruptly to your ball. Walk like you’re drunk.’ ”

At the Masters in 1956, Norman hit his first tee shot while the announcer was in the middle of introducing him. Asked by a playing partner why he took so little time to line up his shots, he said, “Why? Did they move the greens since yesterday?” He once putted between the foot and outstretched arm of a competitor who was marking his ball.

Norman’s background also set him apart. Unlike most of the other top amateurs, he didn’t belong to a country club. He often hitchhiked to and from tournaments, and he had to juggle his competitive schedule with a succession of dreary factory jobs, including one stitching rubber boots. He had to play hooky in order to compete in weekday tournaments, and he was fired five times. “There was no sense saying I was sick,” he says, “because they’d read the headline NORMAN SHOOTS 65 AGAIN AND WINS.” He liked night jobs best, because his days were free to practice.

Simply unconventional

Norman also supported himself by selling the prizes he won in amateur events. As his confidence in his playing ability increased, he sometimes sold the prizes before the tournament began. On at least five occasions, he intentionally finished second because his customers hadn’t wanted the first-place prize.

In 1955, with a birdie on the 39th hole in the final match, he won the Canadian Amateur—the first Canadian to do so since 1951. His victory was widely viewed as a fluke by those who felt that no one with such an unconventional swing and seemingly frivolous attitude could really play golf at the highest levels. But then he won it again the next year, and even more decisively.

At the age of just 27, Norman had now laid the foundation for what might have been one of golf’s greatest amateur careers. But his clowning on the golf course and his penchant for selling his prizes had long infuriated the RCGA. Taking money under the table was a common practice among amateurs, but no player was as open about it as Norman was. The RCGA threatened to strip him of his amateur status. Afraid that he would lose his two national titles, he announced he was turning pro.

This was harder than it sounded. He didn’t have a club job and was an unlikely candidate for one, and thus could not qualify for a Canadian PGA Tour card. Finally, in 1958, under pressure from the public, and with the help of a pro who had hired Norman as an assistant, the CPGA relented. His first tournament as a card-carrying pro was the three-day Ontario Open. He shot 68-69-74 and won by three.

Norman’s obvious next move was to the U.S. tour, to which he won a partial exemption with a third-place finish in a Canadian qualifying event. His U.S. debut took place at the 1959 Los Angeles Open, which was played that year at Rancho Municipal. He putted poorly—a recurrent affliction—but was thrilled to be playing alongside his other golf idols. He continued to play indifferently, with occasional flashes of brilliance until the tour reached New Orleans. There he shot four solid rounds, played in the final group on Sunday, led briefly, and tied for fourth.

Gus and Audrey Maue were in Daytona Beach, Fla., at the time. On Monday morning, Gus saw in the newspaper that Norman had played well and finished fourth. He predicted to his wife that Norman would win the next week, in Pensacola.

“About two hours later,” Maue told me, “there was a knock at my door, and it was Moe. I said ‘Moe, why are you here? You’re supposed to be in Pensacola.’ And Moe said, ‘I will never play that tour again.’ I asked him what had happened, but he said he would never tell me. He was distraught.

“He would come over each night with six Cokes, and we would play cribbage until the wee hours, and the next morning Audrey would wake up, and there would be Moe’s six empty Coke bottles. His heart was broken, but he wouldn’t talk about it,. Then he went back to Toronto.

“A few weeks later, a young tour player I knew came through Daytona, and I asked him what had happened to Moe in New Orleans. He said that some of the big names on the tour—and I’m not going to say who—were upset that Moe was hitting the ball off the big tee, and they were upset with the way he dressed, and they didn’t like his appearance. That’s the bottom line.”

The pros look down

What had happened was that several well-known pros had cornered Norman in the locker room and chewed him out. They told him to stop clowning around, said he had to dress better and have his teeth fixed. It was a harrowing experience for someone who was already painfully shy and socially ill-at-ease, and Norman only rarely went back. He doesn’t like to talk about it now. When Maue told me the story, Norman looked at his feet and said quietly, “It stopped me from having fun.”

The conventional wisdom about Norman’s golf game is that he hits the ball extraordinarily well despite an extremely peculiar golf swing. “Moe’s swing is not fundamentally sound,” Bob Toski said recently. “He gets away with it, I think, because by intuition and by instinct he played that way when he was young. He has great hand and eye coordination, and he has great hand and arm strength. But he doesn’t have the posture of a good player, where the arms look more relaxed and hanging from the body. He has very little bend from his waist. I think he’s another Lee Trevino—he’s a freak. And I use the word in a complimentary sense. He learned his golf swing intuitively, he learned it by trial and error. He didn’t understand the fundamentals.”

Trevino is an interesting comparison, because if you asked other pros to name the best ball-striker among active players, Trevino would get a lot of votes. Are he and Norman really freaks? Or could there possibly be an advantage to having a golf swing that doesn’t look like Bob Toski’s?

Similar thoughts occurred to a Chicago businessman named Jack Kuykendall. In the early ’80s, Kuykendall was a middling middle-age golfer with Walter Mittyish fantasies of making it as a pro. Kuykendall’s handicap was 12. At 44, he decided to devote the next six years of his life to finding out once and for all whether he had the stuff to be a pro.

Two years later, after many hours of hard work, Kuykendall’s handicap was two strokes worse. Frustrated and discouraged, he decided the problem lay not in himself but in the golf swing. “I was convinced,” he says, “that there had to be an easier way to hit a round object on the ground with a stick.”

Kuykendall, a physics major in college, decided the problem was the modern grip. Holding a golf club in the fingers, as virtually all golfers are taught to do, creates a complex mechanical system involving so many different angles, axes and planes that for most players hitting the ball squarely is an accident, Kuykendall believed. He redesigned his golf swing based on the principles he had discovered. After 1½ months of practice, Kuykendall told me, he shot three consecutive rounds below par. The next day, he started a company, which today is called Natural Golf.

Overthrowing the modern golf swing is a big job. Kuykendall peddled his system for several years without much success. Then, one day, after a clinic in California, Kuykendall was approached by a Canadian pro named Mark Evershed, who said: “You’re talking about Moe Norman.” “I still remember my reaction,” Kuykendall recalled. “I said, ‘What’s a Moe Norman?’ ” When he saw a tape of Norman’s swing, Kuykendall was flabbergasted. Point by point, Norman’s swing matched the one he had devised.

“Scientifically, what Moe does is perfect,” Kuykendall says. “It’s what we call an ideal mechanically advantaged golf swing. It is a maximum force with least effort. It’s as perfect as a human being can do. The second-best is Lee Trevino’s. Most people think of his mechanics as unorthodox, but that’s only because it’s not what they’re used to seeing.

“But Lee Trevino and Moe Norman are very, very close in their swings. If Trevino moved his right hand under the club a little more, he and Moe Norman would be identical. The closest on tour right now would be Paul Azinger. He has a single-axis, right-hand grip, like Moe’s, but he also has something that hurts him—a super strong left-hand grip. Moe’s left-hand grip is about as weak as you can make it. Azinger, because of his strong left hand, has to block the ball by spinning his hips to get the clubface square at impact, to keep his left hand from shutting the clubface down. If he moved his left hand to neutral and stopped spinning his hips, he would be almost unbeatable. He would be Moe Norman.”

Kuykendall set out to get in touch with Norman but had no luck for two years. Norman seldom talks to people he doesn’t know. Kuykendall persevered, and eventually Norman agreed to meet him in Florida.

“I spent an hour going through the science with Moe,” Kuykendall says. “When I finished, Moe stood up and pulled some film out of his pocket and threw it on the table. He said, ‘Here, take this. You can help someone with it.’ It was some old black-and-white pictures, from 1966, of what he called his best swing ever. He said, ‘All my life I’ve wondered why I can do what I can do with a golf club. And you are the first person who ever explained it to me.’ ”

Going to market

Meeting Kuykendall was a major turning point for Norman. Natural Golf pays him a fee for the use of his name and image, and he and Kuykendall conduct several dozen clinics a year. Their alliance led to an article in the Wall Street Journal last year, which caught the attention of Wally Uihlein, who is the chairman and CEO of Titleist and FootJoy Worldwide. Uihlein got in touch with Kuykendall and Gus Maue, and arranged to meet with them and Norman at the 1995 PGA Merchandise Show.

“Mr. Uihlein told Moe that Titleist would like to shoot a video,” Kuykendall told me, “so that his swing would never be lost. The Titleist booth had one of those big blocks of video monitors, and Moe said, ‘Can I be on there next year? Can I be on there next year?’ And Mr. Uihlein said he could.”

Uihlein then told Norman that Titleist would like to pay him $5,000 a month for the rest of his life.

“Moe looked kind of funny,” Kuykendall says. “He took a step backward and said, ‘I’ve played your balls all my life. What do I have to do for that money?’ And Mr. Uihlein said, “You don’t have to do anything. You’ve already done it. We just want to thank you for what you’ve already done.’

“Mr. Uihlein said that Moe was in the same league as Ben Hogan and Bobby Jones, and he deserved the same kind of respect. Moe didn’t say anything. He just went limp, and he almost went into shock. I thought he was going to pass out. By that time, the hair was standing up on my arms, and all of us who were there were about to cry. Moeand I had to go do a clinic right after that, and in the car on the way there, Moe said, ‘Jack, I don’t know if I can hit the ball.’ ”

The Titleist stipend has made a huge difference in Norman’s like. He still lives in the same motel room, eats in inexpensive restaurants and keeps his clothes in the back seat of his car. But he doesn’t have to worry about money anymore. Eight years ago, Norman told Gus Maue that he was worried he’d never be able to afford to get back to Florida, saying, with deep sorrow, “My days are through.” Today, he can go anywhere he wants.

Even more important, Norman has finally received the kind of recognition that throughout his playing career he felt he was denied. He sometimes grumbles that his induction to the Hall of Fame came 20 years too late, but he is nonetheless pleased to be there. Recently, he has even begun to talk about returning to competitive golf, perhaps by playing some events on the U.S. Senior tour.

Although the Hall of Fame induction was a great honor, most people who hear Norman’s story end up feeling that a huge opportunity was missed. If circumstances had been different—if he’d had a sponsor, if he’d had a mentor, if other players had been kinder, if he had worked harder on his putting—could he have dominated the PGA Tour?

The more I think about it, though, the more I think the question misses the point. The most striking fact about Norman’s competitive record is not that it falls short of Hogan’s or Nelson’s or anyone else’s but that it exists at all, especially if Norman is disabled in anything like the way people who know him speculate that he may be.

Norman overcame gargantuan obstacles as a young man and then went public with a golf swing that provoked titters. He set out to learn how to hit a golf ball, and he worked at it until he could do it better than anyone else. His succeeding required a skill and courage and self-assurance on an almost inconceivable scale.

The difficulties Norman endured undoubtedly took a toll on him. “When the sun goes down,” Gus Maue says, “Moe is a very, very lonely man. He goes back to his motel room and turns on the TV. He’s fine during the day because he can play golf, but at night he doesn’t know what to do.”

That’s Maue talking, not Norman. Norman speaks freely about injustices he feels he’s suffered, but he doesn’t dwell on the dark side of his life. For all he’s been through and all the hard times he has seen, it is not his sorrows that stand out. Norman with a golf club in his hands looks like a happy man. Even back in the days when he practiced till his hands were bleeding, golf for him was a source of joy. It was that attitude, as much as anything, that got him into trouble with various authorities—as in the tournament in which he came to the final green with a three-stroke lead, intentionally putted into a bunker, and got up and down to win anyway. That attitude has also sustained him.

“Golf is to have fun,” he told me toward the end of our conversation, repeating a theme he had brought up before. “What do you have to lose? A lousy ball, that’s all. If you lose yours, grab another one out of your bag and hit it. That is what the game’s about, and that is the first thing I was taught 55 years ago: Have fun. Most golfers don’t see the bright things. All they see is the bad.

“But if you see the bad things, that’s where your mind will take you. If you drive a car down the road and look at the sidewalk, where do you think you’re going to put the car? It’s the same thing on a golf course. People see only trees and water. But I don’t. To me, they are only there as an ornament. They are there to make the course look nicer. All I see is the tee, middle of the fairway, and middle of the green. That’s golf. I hit my 18 fairways and 18 greens, and go on to the next day.”

“Gee, Moe,” I said, “it must be boring for you.”

“Like heck it is,” Norman said. “That’s fun.”