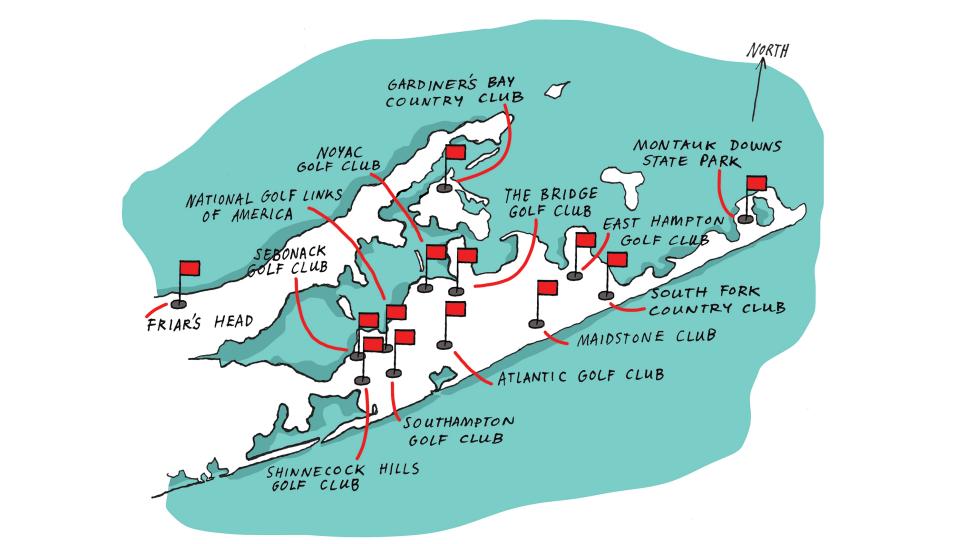

With the possible exception of California's Monterey Peninsula, home to Pebble Beach, Cypress Point, Spyglass and others, there isn't a denser concentration of great golf in the world than on the eastern end of New York's Long Island.

Shinnecock Hills, host of this summer's U.S. Open, is fourth on Golf Digest's ranking of America's 100 Greatest Courses. Four other top 100 courses lie within 20 miles: National Golf Links (No. 8) and Sebonack (No. 41), which are right next door to Shinnecock, plus Friar's Head (No. 19) and Maidstone (No. 72). Add in Southampton, a fine 1925 Seth Raynor design that also borders Shinnecock, and a handful of superb more recent arrivals, and you've got a lifetime's worth of fabulous courses to play.

Except, of course, that you probably can't, because you'll almost certainly never get on.

Most golf in the Hamptons, as the tiny, oceanfront tip of Long Island is known, is private. Not just ordinary private, but Big Time, Blue Blood, Big Money private. Extravagant wealth, fame and power are such distorting factors in the Hamptons—where renting a house for the summer can cost $1 million and Kardashians hobnob with senators and tycoons—that it requires extreme effort to wall off golf from the glitz.

The ideal of golf in the Hamptons is not Trumpian excess (no fountains, please), but the Shinnecock model of rugged, understated perfection. For those with access, golf is the antidote, not the apotheosis, of the fevered Hamptons vibe.

This takes money. There's no way around it in the Hamptons. But that money, for the most part, doesn't buy stuffiness or pretension; it buys ease, seclusion and majestic views.

The Bridge, which opened in 2002 and is one of the newest clubs in the Hamptons, has an initiation fee of about $1 million. Yet it is anything but a hidebound, traditional club. Wearing jeans, cargo shorts or a cap turned backward is not only OK, it's encouraged, if that's how you want to express yourself. The glass-walled, modernistic clubhouse looks like a turbine engine spun out of control. The most spectacular views of the Rees Jones course and Peconic Bay are not from the dining room but from the expansive locker rooms, because that's where members hang out most.

Even at Shinnecock, the oldest (1891) and most alpha of the Hamptons golf clubs, the atmosphere is laid back and modest. The Stanford White-designed clubhouse, perched above the ninth green with panoramic views of the course, Peconic Bay and the Atlantic, is beautifully maintained, but first-time visitors are often surprised that it's not more... fancy. The wood floors, smallish club rooms and wraparound porches are remnants of another era that no one at the club has any desire to gussy up.

FOR THOSE WITH ACCESS, GOLF IS THE ANTIDOTE, NOT THE APOTHEOSIS, OF THE FEVERED HAMPTONS VIBE.

Women's golf is very active at Shinnecock, and in recent years the club has invited more locals to join. The main criterion? A love of golf. Members include Raymond Floyd, who won the 1986 U.S. Open there and recently put his Southampton house on the market for $17.5 million, and Pink Floyd co-founder Roger Waters, who is said to play twice weekly.

If Shinnecock, by dint of its course and championship history, is the alpha Hamptons club, National and Maidstone are close betas. "The National," as members call it, opened for play in 1911 with holes designed by Charles B. Macdonald in homage to the most distinctive holes in Great Britain. Many if not most of the copies now surpass the originals in playability and strategic nuance; the delight of a round at National is the never-ending variety of challenge. Membership at National, which now includes (a few) women, is a bit more nationally oriented than Shinnecock's. The course is seldom crowded, but play by unaccompanied guests is allowed and financial firms with membership ties to the club sometimes bring out groups of four or five foursomes.

Illustration by Harry Malt

Maidstone as a golf course doesn't get the respect that Shinnecock and National do, but a 2012 renovation by Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw masterfully restored the shot values and rugged aesthetics of the original 1924 design by Willie Park Jr. and his brother Jack. Located 17 miles from Shinnecock and directly on the beach, Maidstone has some of the few genuine links holes in North America. "If I had to choose one course to play and walk every day for the rest of my life, it would be either National or Maidstone," says Rod Aboff, a single-digit handicapper who grew up and still lives on Long Island and has played courses around the world, "but I'd probably go with Maidstone. The holes along the ocean are amazing, but so are the other holes that run along the inland waterways."

Maidstone is known as the most blueblood of the Hamptons courses, but that blueness is judged primarily on the long-standing-ness of connection to the East Hampton community rather than on strict, social-register pedigree. (Chevy Chase is a member, so go figure.) Unlike Shinnecock and National, Maidstone is a full-service family club, with a grand swimming pool and dozens of private cabanas on the beach that, like memberships in the club, pass down like heirlooms from generation to generation.

After super Big Money hit the Hamptons in the 1980s, newcomers started building expensive, top-shelf clubs of their own: Atlantic (1992, course by Rees Jones), East Hampton (2000, Coore and Crenshaw), and Sebonack (2006, Tom Doak and Jack Nicklaus). The sublime Friar's Head (2002, Coore and Crenshaw), with holes extending out to the bluff overlooking Long Island Sound, isn't technically in the Hamptons, but it's nearby. Its old-school ethos—range finders forbidden, hole yardages not printed on the scorecard—carries the purist Hamptons golf worldview to its extreme.

Sebonack is another $1-million club to join, but the multitude of on-site, four-bedroom cottages help out-of-town members defray costs; they don't absolutely have to have a $30 million Hamptons home of their own.

It should be noted that the older clubs, with land and clubhouses mostly paid off, have only recently approached or breached the six-figure milestone for initiation fees; getting in is the hard part, not coming up with the cash.

For those still waiting to join a Hamptons golf club, or just passing through, there's Poxabogue, the always-busy practice range on the main spinal highway with a nine-hole par-30 course tucked behind. Summer traffic in the Hamptons is so congested that you can sometimes find members of the heralded private clubs hitting balls here, to avoid the interminable drive to their clubs.

By far the best public option is Montauk Downs at the far tip of the South Fork. Redesigned in 1968 by Robert Trent Jones Sr., with help and subsequent updates from son Rees, the windswept course is a worthy challenge with splendid bunkering. Plus, if you're a member of New York State (that is, a resident), you qualify for half-price green fees and other advantages when booking. Who said you don't belong in the Hamptons?