From the Golf Digest Archives

Pete Dye's Final Chapter

Editor's Note: This story first appeared in the November 2018 issue of Golf Digest. Alice Dye died on Feb. 1, 2019 at age 91. Pete Dye died on Jan. 9, 2020 at age 94.

“Please don't end your story on a sad note," Alice Dye says to me as I close my notebook and reach over to shut off my voice recorder.

"I won't," I say, not believing I can keep the promise even as I say it.

How can this not end on a sad note? This entire situation is sad, even tragic. Iconic golf-course designer Pete Dye, author of TPC Sawgrass, Crooked Stick, the Ocean Course at Kiawah, Whistling Straits and many others, a genuine genius at his craft, member of the World Golf Hall of Fame, Alice's husband of 68 years, the love of her life, sits in a rocker some 10 feet from us, seemingly oblivious to our presence. He looks healthy, maybe a bit puffy in the face, remarkably good for nearly 93 years old. But time has robbed him of his verve. He's now almost childlike, his attention not on us, but on a rerun of "Gunsmoke" on television. In the good old days, 30 years ago or three, I couldn't have had a conversation with Alice without Pete jumping in. Likewise, if I'd ask Pete a question, Alice would invariably cut him off with the answer.

The two of them used to constantly talk to me at the same time, much as my parents used to do. During rounds of golf with Pete and Alice, they'd not only talk at the same time, they'd swing at the same time. The only three-hour rounds I ever played were with them.

This day in August, we're sitting in the Dye home on Polo Drive in Gulf Stream, Fla., their primary residence since 1971. Alice, 91, is in a wheelchair, temporarily, with her left leg outstretched, a drainage tube leading from her kneecap, the result of complications after knee-replacement surgery. She's on the mend but frustrated at the slow pace of her recovery and how it inhibits her caring for Pete. There are three others in the house to watch over both, but still, that's her husband who needs her help.

An orderly walks Pete from the kitchen to the den, eases him into the rocker, then turns on the television. The orderly tells Alice that he has fed Pete lunch, strictly soft food now, after a choking incident a week ago that resulted in an emergency-room visit. In a loud voice, Alice announces my presence to Pete, but he just stares at the TV.

Pete's mind is in a state of irreversible decline. Call it what you will: dementia, Alzheimer's, old-timer's disease, a total eclipse of the brain. Whatever it is, it is cruel, robbing him of his memories. It's also stripping away his personality. To me, Pete was always a combination of Will Rogers, Walt Disney and Rod Serling. Now he's barely Pete. It is heartbreaking.

I ask Alice if Pete is aware of who we are, or, more important, who he is anymore.

"I don't know what he knows," she says. "It's very strange. He doesn't communicate back much. But I think he understands more about what's going on than we think."

I guess I'd seen it coming but didn't recognize it for what it was at first, or maybe I was in a state of denial. During a round of golf in 2015 with Pete and Alice at Gulf Stream Golf Club, just down the street from their house, Pete had asked me a question, then five minutes later asked me the same question again. And he kept calling me by the wrong name. I dismissed that as the usual forgetfulness that comes with old age.

Last year, when Alice was presented the Donald Ross Award by the American Society of Golf Course Architects, Pete stood off to the side. When I walked up to him, he shook my hand and said, "How ya doin'? How ya doin'?" But I noticed he said the same thing to everybody else, too. He doesn't remember anybody's name, I thought. Now I'm not so sure he recognized any of us.

This day, Alice urges me to slide my chair over and speak to Pete. "He'd be upset if you didn't," she says.

I scoot over and gently touch him on his right shoulder. He turns his head and looks at me blankly for a moment, then starts to smile.

"Pete," I say. "How ya doin'? It's Ron Whitten. Golf Digest."

His smile is now a grin, and he mouths something over and over, chewing on a word. To me it sounds like "right" or "write" or "writer."

"I'm a writer," I confirm. "I'm writing an article on you."

Pete chuckles repeatedly, and I'm suddenly overcome with emotion. Because I think he recognizes me? Because he can barely talk? Because I'm powerless to help him? Probably all that, but in hindsight, I think I felt overwhelmed mainly because it was the same chuckle I'd heard from Pete so many times before. His chuckle seemed to indicate to me that he's content, OK with his fate, not fearful. Would that I could be as brave.

"I just wanted to see you and tell you how much I love you," I say. He responds with more chuckles as he mouths another word, one that doesn't fully materialize. "You've given me so many fine hours of your time over the years, I wanted to thank you. You've given me great stuff to write about," I tell him. I ramble a bit more, my voice choking. "I'm so pleased to see you again."

Pete continues to look at me, then his eyes turn left and he's staring at the television. I squeeze his hand, and he looks back.

"Take care, my friend," I say, and I hear him respond, "Yeah." I repeat myself as I take off my glasses and wipe tears from my eyes. "Take care," I say again, and I hear a faint, "I will." Or did I?

Listening to the exchange later on my voice recorder, a faint recording because it was positioned several feet away, next to Alice—I hadn't had the presence of mind to carry it over to Pete when I spoke to him—I rewind and play the portion over and over. I can definitely hear Pete say, "Yeah." But the other response, "I will," wasn't from him at all. It was spoken by someone on the television. Damn. What are the odds of that particular piece of dialogue at that precise moment?

As I rejoin Alice, she says, "I think he knows. Don't you?"

I try to respond, but I'm sobbing.

‘It’s really hard to see that brilliant mind slipping away. All that creativity and imagination … ’Alice Dye

GROUNDHOG

Pete's mother, Elizabeth, who also lived into her 90s, had kept a scrapbook of his school-age activities. After Pete and Alice wed, Alice kept scrapbooks of their joint accomplishments in golf and business. The scrapbooks became weathered and fragile, so a few years back, Ken May, longtime photographer for Dye Designs, reproduced every item from every page, almost 8,000 shots in all. With Alice's permission, I reviewed the electronic version of a lifetime—two lifetimes, in fact—recounted in faded photos and sepia-toned clippings.

It starts with his birth certificate, Paul Dye Jr., no middle initial, born Dec. 29, 1925, in Springfield, Ohio. As a youngster, to distinguish him from his father, Paul Francis Dye, people called him by his initials, P.D., which became Petey, which became Pete.

There's a 1936 clipping, under the heading "Boy is Political Orator," showing a photo of Pete at 10, stealing the show with a speech at a Democratic rally to re-elect FDR as president. "You think I'm for Roosevelt because my daddy is," Pete is quoted. "That's not the reason. ... In 1932, lots of kids came to school without enough clothes to keep them warm. ... Now when I go to school, these kids have plenty of clothes and plenty to eat. That's why I'm for Roosevelt." (Pete would change his political affiliation as an adult but would never lose that populist passion.)

His father was an insurance salesman, local postmaster and amateur golf-course designer. In 1922, he built a nine-hole course, Urbana Country Club, where Pete would learn the game at an early age and become a good player. As a junior at Urbana High, he won the individual title at the 1943 Ohio High School Golf Championship. Others who have held that title include famed journalist James (Scotty) Reston in 1927, golf architect Jack Kidwell in 1937 and Jack Nicklaus in 1956.

Pete didn't defend his title the next year, the papers reporting that he'd left school to enlist in the service. In May 1943, he had passed 20 hours of training in Aerial Navigation with the intention of joining the Army Air Corps. But his father wanted him to finish high school first, as a letter read:

"I am sending Paul Jr. to Asheville School, Asheville, N.C., for his senior high school year. He is to take subjects which will help qualify him for the Air Corps, and his schedule has been arranged by me with the headmaster. He has been a B student at Urbana High School the past three years. In July of 1942, he was appointed manager and foreman of our country club and golf course and has had complete management of the plant for the last 14 months. He is a good mechanic and has unusual mechanical experience for a youngster his age. Wanted to bring out the above point about this boy, as he is a conscientious worker."

When I mention Pete's stint as greenkeeper at Urbana to Alice, she laughs. "Pete tells me he was horrible at that. Didn't know what he was doing."

He enrolled at Asheville, but as Pete wrote in his 1995 autobiography, Bury Me in a Pot Bunker, "Much to my father's displeasure, all I did in Asheville was play golf and have fun." He left in the second semester and joined the Army, assigned to the parachute infantry after basic training, stationed at Fort Benning, Ga., and then Fort Bragg, N.C. At both places, he was put in charge of maintaining the camp golf course. At Fort Bragg, he'd sneak away regularly to play golf in Pinehurst, some 30 miles away, one time joining a group that included department-store king J.C. Penney and Pinehurst's course architect, Donald Ross. At the time, Pete later said, he was more impressed with Mr. Penney.

Pete spent his last 60 days at Fort Bragg in a prisoner uniform after forging a pass to attend his younger brother Roy's high school graduation from Asheville School. Pete was then told to prepare to be part of the invasion of Japan, but two A-bombs were dropped, and Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945.

"I'm sure Harry Truman saved Pete's life," Alice says.

Despite not having a high school diploma (Asheville would present him an honorary diploma dated 1944 in 2002), Pete enrolled at Rollins College near Orlando on the GI Bill. There he met Alice Holliday O'Neal, a junior pre-med student and accomplished golfer who had won the Indiana Women's Amateur that summer. She was smitten by his wit and good looks but a bit uncomfortable with his cavalier nature. "Like many other servicemen," Alice wrote in her 2004 autobiography, From Birdies to Bunkers, "he wanted to have some fun. ... He won bets by jumping off a bridge onto a boxcar of a train and riding on the top to Tampa, but mostly he just skipped class and played golf."

Oh, Pete was charming. After a year of dating, Pete gave Alice a ring, inscribed "Oct. 16, 1946," to commemorate the day he first met her.

Alice graduated in 1948, returned to her native Indianapolis and sold insurance for Connecticut Mutual, an unusual move for a woman in that era. The same spring, Pete dropped out of Rollins and enrolled at Ohio Northern University. But he soon left and returned to Urbana, where he, too, became an insurance salesman, for his father's company, Northwestern Mutual.

Pete and Alice continued their courtship for two years while playing competitive golf. He made it to the semifinals of the Ohio Amateur in the summer of '49 and qualified for the U.S. Amateur at Oak Hill in Rochester, N.Y., losing in the third round to local favorite Sam Urzetta, 5 and 4. Meanwhile, Alice won the Indiana Women's Amateur twice more, in '48 and '49. She'd win the Indiana Amateur nine times, her final victory in 1969.

In the spring of 1949, Pete went to Indianapolis, presumably to ask Alice's parents for her hand in marriage, but he played three rounds of golf instead.

"What about getting married?" Alice asked in exasperation.

"Not in the golf season," Pete replied.

Their engagement wasn't announced until December 1949, and they wed on Feb. 2, 1950, Groundhog Day. In the scrapbook, there's a Western Union telegram from Pete to Alice with just one word: "Groundhog."

"Was that his proposal?" I ask Alice.

"I don't recall. What's the date on it?"

At first, I don't see one, then notice a date stamped across a corner, Jan. 30, 1950, just three days before the ceremony.

Alice shakes her head. "I don't remember what that was about. My mother set the wedding date."

They were married at her parents' home in Indianapolis, had a reception at nearby Woodstock Country Club, honeymooned in Orlando, then settled in Indianapolis, where Pete began representing Connecticut Mutual. Alice left the company, wanting to concentrate on home and golf. Their first son, Perry O'Neal Dye, named for Alice's father, was born in September 1952. Their second son, Paul Burke Dye, now known as P.B., was born in July 1955. Both sons are accomplished golf architects of longstanding; in 1992, P.B. expanded the family's Urbana Country Club to 18 holes.

The gregarious Pete was a natural salesman. In 1954, he was inducted into the Million-Dollar Round Table of the National Association of Life Underwriters, a major achievement in the days of small policies. He kept up that pace for the next four years.

"Pete spent most of his time in the evenings with pre-med students at the Indiana Medical School, convincing them to buy life insurance," Alice says. "He'd play golf during the day and work at night."

He won local and regional events but lost in the final of the Indiana Amateur in 1954 and '55. In 1958, he finally prevailed, winning at Morris Park Country Club in South Bend with his parents in attendance.

Pete also spent a great deal of time as green chairman at the Country Club of Indianapolis, even attending agronomy classes at Purdue University to gain knowledge. He enjoyed going out to the country club and tinkering with its design.

"He started moving bunkers and planting trees and doing things out there until he had the members about crazy," Alice says. "There was a brown portion of one fairway [where Pete had sprayed chemicals to kill weeds and improve the turf] that was known as 'the Dye half.' "

In 1959, Pete announced he was bored with the insurance business and wanted to build golf courses. Alice wasn't worried about a drastic drop in income.

"Back then, when you sold a policy, the agent got 50 percent of the premium the first year and then another 5 percent each year for as long as the agent serviced the policy. Pete had built up a nice income, so we had money that allowed him to design courses and still pay the bills."

Pete took out a newspaper ad that declared him to be a golf-course architect. Alice's father, a lawyer, told Pete that was false advertising because he didn't have a degree in architecture. From that point on, Pete always called himself a golf-course designer.

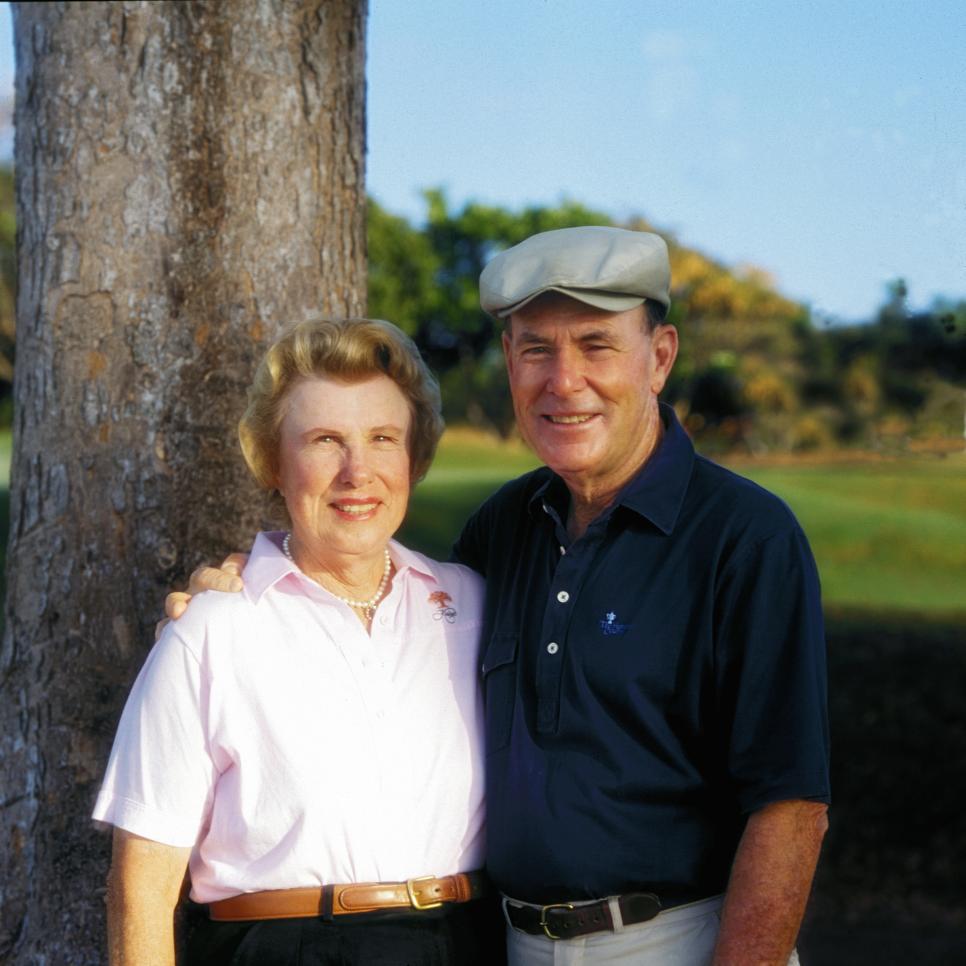

Photo by Dom Furore

There are several articles in the scrapbook that indicate Alice was intimately involved from the beginning. She's pictured on sites during construction. She presented the $200,000 budget to Indianapolis city fathers for the construction of North Eastway Golf Course, which she'd routed like the Star of David, she says, so every third hole would return to the clubhouse, allowing customers to buy another hot dog and use the facilities. She did the diagrams of course routings featured on the newspaper front pages. Columnists wrote about courses "designed by Alice and Pete Dye."

I tell Alice that it seems designing courses was as much her dream as it was his.

"Oh, I followed along because that's what my husband wanted to do," she says. "But I enjoyed it. Still do."

GOLDEN BEAR: COMPETITOR AND COLLABORATOR

A major part of Pete Dye's legacy is the legion of present-day golf architects who got their start being mentored by Pete: designers like Bill Coore, Tom Doak, Tim Liddy, Greg Muirhead, Lee Schmidt, Bobby Weed and many, many others. "Everybody who ever worked for dad considered [Pete and Alice] their parents. That's because they treated every one of them like their son," P.B. says. "It's like they had a hundred kids. I lost track of the number of guys who said Pete would bring them lunch, a sandwich and a bag of chips, and the bag of chips would always be open, half-eaten. That's Dad for you."

The Dye scrapbooks are silent about most of these "Dyeciples," except for Jack Nicklaus. Jack is featured on many pages, as golf competition at first.

Dye and Nicklaus faced one another for the first time on Labor Day 1957, when Pete, 31, and Jack, 17, the National Jaycee champion, played in a fundraising exhibition arranged by Pete's father at Urbana Country Club. The headliner was Sam Snead, with reigning Ohio Amateur champ Bob Ross Jr. filling out the foursome. (In 1946, Pete had defeated Ross to win the Springfield Country Club championship.) Slammin' Sammy shot even-par 70, Pete 71, Jack 75 and Ross 76.

This was the second time that summer that Pete had bested Nicklaus. They had qualified for the U.S. Open at Inverness, but both missed the cut. Pete's two-round total of 12 over par tied Arnold Palmer and was eight strokes better than Jack.

The next year, Pete played against Jack again, in the semifinals of the Trans-Mississippi Amateur at Prairie Dunes Country Club in Kansas, with Jack winning, 3 and 2, en route to the title. In 1964, at Pete's urging, Alice qualified for the U.S. Women's Amateur at Prairie Dunes, mostly to experience its prairie-links layout. Like Pete, she made it to the semifinals and, like Pete, lost to a future legend, JoAnne Gunderson (Hall of Famer JoAnne Carner). The Great Gundy, however, lost in the final to Barbara McIntire.

Jack says one of his next encounters with Pete happened in 1965, at The Golf Club, an exclusive private course east of Columbus that Pete was building for insurance man Fred Jones. (Before Nicklaus turned pro, Jones had given him his first real job, selling life insurance.) Pete invited Jack to the construction site to offer suggestions. Jack told him he didn't know anything about design.

"Pete said, 'You know more than you think you know,' so I took him up on it," Jack says. "The place was still dirt. The second hole went up and over a hill. I didn't like it. Still don't. The par-3 third had a round green surrounded by four round bunkers. I told him it looked like Mickey Mouse and suggested he move one bunker closer to a nearby creek and shift two other bunkers around. I made suggestions to three or four other holes, and Pete told me they were great suggestions. I was flattered.

"That's when Pete asked me if I'd like to consult on some designs," Jack says. "I told him if we could work things out, that would be great."

They met again at the 1966 Masters, where Jack had a group of Ohio friends eager to build a new private course on land northwest of Columbus. Pete looked at the property and worked up an 18-hole routing for Jack. Pete's design was never built, but in 1974, with a different routing on much the same land, the site became Muirfield Village Golf Club.

In early 1967, a magazine ad appeared, announcing Jack's availability "for design of selected golf courses." It was illustrated with a photo of Jack standing on a golf course, pointing in the distance, next to Pete, holding a set of plans. It clearly implied a design partnership between the two. But Pete was not identified in the ad.

That might have been a disappointment to him. After all, Pete is quoted in a 1969 Golf Digest article saying, "Jack is my consultant. In the newspapers, it always comes out that I'm his assistant secretary or something."

But Alice says Pete never worried about such things.

"Pete has never had any pride," she says. "Never did. He just wanted to build golf courses, like a kid wanting to play with clay. He wanted to create something special, something unique."

Pete and Jack collaborated on just four projects, the first being their best, the landmark Harbour Town Golf Links on Hilton Head Island, which opened on Thanksgiving weekend of 1969 by hosting the second-to-last PGA Tour event of the decade, the Heritage Classic. It started with a literal bang, Jack topping the ceremonial opening tee shot a mere 30 yards as a cannon boomed during his downswing, and finished with another, Arnold Palmer winning by three.

"Our fee was $40,000," Jack recalls. "We lost money. I made 23 visits in my airplane, never got reimbursed, but it was the greatest experience of my life, working with Pete and with Alice. We lost money on the other projects, too. I finally told him, 'Pete, I love you, but I can't afford you.' So we split up."

Besides Harbour Town, Pete has had the good fortune to build other courses that have debuted as hosts of major golf events, the sort of publicity any architect craves. There was TPC Sawgrass, built for his old friend Deane Beman, then commissioner of the PGA Tour. Its radical design was unveiled at the 1982 Players Championship, won by Jerry Pate, who after holing the final putt, tossed Beman and Pete into a lake along the 18th green before diving in himself. "I was hoping an alligator would get all three," Lee Trevino told reporters.

There was also PGA West in La Quinta, Calif., exceedingly difficult with a 20-foot-deep bunker called "San Andreas Fault" (wags called it "Pete's Fault"), introduced to the golf world via the 1986 Skins Game featuring Nicklaus, Palmer, Trevino and Fuzzy Zoeller. Fuzzy won most of the dough.

And there was the Ocean Course at Kiawah, built for the 1991 Ryder Cup and barely completed in time for that September showdown. Nearly three decades later, it's still remembered as the battleground for The War by the Shore.

CANDLELIGHT

I first met Pete Dye at the 1982 annual meeting of course architects in Palm Beach, invited there by Geoff Cornish, with whom I'd just co-authored a history of golf design called The Golf Course. "You're too young to have written that book," Pete said when we were introduced.

I met Alice that same week. She became a member of the society the next year, the first female accepted, and she soon asked me to help her write a publication advocating sensible forward tees for women. It became a widely circulated pamphlet and poster titled Creating a Two-Tee System for Women—It's Time to Move Forward.

I first interviewed Pete in 1983 during construction of Firethorn Golf Club in Lincoln, Neb., a low-budget marvel developed by Dick Youngscap, who would later gain national prominence establishing Sand Hills Golf Club in the middle of the state. I still have the tape recording of my interview with Pete, which focused on his alternatives to traditional rough.

"Everybody at first thought waste areas were all going to be just sand all the time," he said. "But that was never the original intent. The idea was to create Scottish waste areas, some with the grass completely out of them, some with a heather or a gorse-type bush in them. You don't want them to all look alike."

We also talked bunkers. "The more I look at it," he said, "the more I think I ought to make bunkers either real big or real small. The bigger the bunker, the easier it is to maintain. But it's the tiny ones that are fun to play."

Pete has forever reinvented his art. Whenever I'd visit him on a construction site, he'd show me some new wrinkle. At French Lick in southern Indiana, it was multiple-purpose fairways, very wide corridors of low-mow bluegrass for average golfers, who prefer the ball sitting up, and within those fairways, slender corridors of bentgrass with tighter lies. Pete reasoned that, for a big-time pro event like the PGA Championship, they could narrow the fairways simply by letting the bluegrass grow, thus avoiding any resodding.

He hung chicken wire to create vertical edges along his water hazards at Kiawah, and for the bulkheads at Brickyard Crossing, the remodeled Speedway 500 Course in Indianapolis, he used large chunks of concrete walls just removed from the Indy racetrack. He pointed out tire burns in the concrete to me, long streaks of black rubber.

Brickyard was a particularly memorable visit. In response to an article I'd written about Pete's three-year stint in the early '60s as tournament director of the Indy 500 PGA Tour event, Pete and Alice invited my wife, Lynn, and me to join them for the 1993 race. Pete and I toured the just-completed course, covered with race spectators on the infield holes (his spectator mounds facing the racetrack), then joined our wives in CEO Tony George's skybox above the finish line.

Later that same year, Pete had me come down to Florida to show me a new "positive drainage system" he'd installed at Old Marsh Golf Club north of West Palm Beach. It was basically drainpipes connected to pumps, an idea he'd gotten from a Popular Mechanics magazine article. We stood in the rain of Tropical Storm Gordon, watching rainwater in fairway catch basins swirl and drain away like bathtubs emptying. Pete then had me drive him over to Seminole Golf Club for comparison. We'd walked out onto its squishy fairways, where he hoped to install the same system, when the full brunt of the storm smashed into the coast. Our umbrellas disintegrated, and we clung to the trunks of palm trees to keep from being blown away. When the rain let up, the course appeared to be one big lake, so we cautiously followed the tree lines back to the empty clubhouse. The power was off, so we wrung out our clothes as best we could and drove to Pete's house. Alice served us dinner by candlelight on TV trays.

That's one of several times when Pete has thumbed his nose at the Grim Reaper. Another was his well-publicized surgery for colon cancer in 2002.

"It was on Friday the 13th," Alice recalls. "Pete figured nobody else would be on the operating table that day. After the surgery, they told him he'd still need chemotherapy. He told them he wanted to keep working on his courses, so he'd take a low dose of chemo every Friday and then go back to work every Monday. He did that for a year. Didn't lose his hair or anything. And it worked. He's never had a recurrence."

Less publicized was Alice's bout with breast cancer in 2010. She's a cancer survivor, too.

In 2008, Pete was building Dye Fore, his fourth layout at the Casa de Campo resort in the Dominican Republic. As he examined the championship 10th tee on a bluff overlooking the Chavon River, he stepped backward and straight off the edge of a precipice, tumbling some 200 feet down a briar-patch-filled cliff until a bush snagged him. The maintenance crew had to climb down and carry him back to safety. Pete was scratched and bruised but had no broken bones. He didn't mention the incident to Alice until weeks later, when he could no longer tolerate the back pain. She made him go to a doctor, and he subsequently had minor corrective surgery.

Photo by Rolling Greens Photo/Ken E. May

BRILLIANCE

As I review the final pages of a scrapbook, I try to put Pete's architecture into perspective. It seems to me, I say to Alice, that Pete always built holes to test the good golfer, the tour pro, and that her role was to constantly remind him that average golfers needed to get around his courses, too.

"Well, if you look at his courses, he almost always has an open approach in front of his greens," Alice says. But, she says, "I'm the one who put the wall of boards up in front of the 13th green at Harbour Town. I'm the one who told him to turn the 17th at TPC into an island green."

"And you're the one who added that nasty bunker right in front of the green at the 17th at Whistling Straits," I add, and Alice nods in agreement.

"The main thing about Pete's career," she says, "was that he had courage to do what nobody else would do. He went way out on a limb with every golf course he built. And the next one wasn't anything like the course he'd just built.

"Every single green he built was a fresh idea. He never went to a drawer and pulled out a drawing, because we don't have any drawings of his greens. Every green came from his head, a new idea on that particular spot. He's done all the greens on all his courses." Alice folds her arms and looks at Pete.

"It's really hard to see that brilliant mind slipping away," she says. "All that creativity and imagination ... "

Sitting in my office a week later, I listen to her comments on the recorder and find myself disagreeing on one point. Yes, that brilliant mind is slipping away, but I don't think his creativity and imagination are. Both are still on display at every course he ever designed (145 originals and 24 remodels).

Some are adaptations of ideas from places he'd played in his competitive days. Camargo undoubtedly inspired his greenside bunkers built at different levels. The wiregrass rough at Pinehurst No. 2 led to him adding a variety of textures using turfgrasses. His rounds at Scioto in Columbus and Broadmoor in Indianapolis, also Donald Ross designs, are reflected in the deception bunkers placed well short of putting surfaces that seem right up against the collars.

There are special touches in his work: a sod-wall bunker at The Golf Club, quite possibly the nation's first; water hazards perched above fairways at The Honors Course; the tee-box-on-stilts at Kingsmill; the triple-fairway par 4 at Blackwolf Run's River Course.

There are incomparable stretches, like the string of eight holes just above the Caribbean at Teeth of the Dog.

Most of all, there's the consummate lines-and-angles architecture he has displayed at every stop, where you have to challenge a hazard to open up the next shot.

None of us will be around in a hundred years, but I'm certain that Pete Dye's architecture will still be here, studied by students of the game, cherished by historians and preserved by proud club members as classic golf courses.

And that's a happy thought.