The wizard Of Bandon Dunes

Grant Rogers, director of instruction at the Oregon golf resort, sounds off on slow play, gambling precautions, time management, Tibetan bandits, clarinet lessons and the power of a root-beer float

EARLY IN THE ROUND of a playing lesson at Pacific Dunes, my student made a 10. It was freezing, the wind was howling, and I hadn't said much to that point. "What do you have to say about that?" he snapped after taking the ball from the hole. I said, "Remember, the golf holes like to win, too." Look, no modern architect is going to give you a bunch of kick-in birdies. When Bandon Dunes' owner, Mike Keiser, commissioned David McLay Kidd, Tom Doak, Jim Urbina, Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw to design these courses, he told them to defend par. So you're going to win a few times, but the holes also are going to get their pound of flesh.

SAME GUY, a few holes later. He faced a shot that only the courses at Bandon can give you: 180 yards through a brutal crosswind, a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean immediately left of the green. Bailing to the right was no bargain, either. He put his hand on his 4-iron, then backed off. He took out his 3-wood, then put it back. He looked at me kind of helplessly. "There's nothing in that bag that's going to help you today," I laughed, and kept walking. He was steamed for a while, but like everyone who comes here, he quickly discovered you can't always pay too much attention to par on the scorecard. Par makes you do things you shouldn't try to do. It messes with your ego and your mind-set. It's one reason people leave here better, more enlightened players.

COURSE MARSHALS should try driving up on a slow group and telling them, "I've been following you, and I see that you're picking up the pace. Great job." I saw a marshal take this positive approach, and it really got people moving. It also made the marshal feel better about his job, which can be a tough one. Who likes to see a marshal coming up on their group?

THE MARSHALS don't hassle players who learn the game from me. I spent a summer with my grandmother in northern Minnesota when I was about 10. I played with some other boys on a nine-hole course with sand greens. The pro at that course was always telling us to "miss it quick," an expression he got from George Duncan, a Scottish pro who won the British Open in 1920. To this day I'm a very fast player and teach beginners to play quickly, to take aim at your target and then swing at the ball. If there's one thing I know to be true, it's that taking extra time doesn't help.

IF YOU BELIEVE THAT A DEITY influences everything, then that would have to include golf. Life is mostly troubles, interspersed with little bits of divine intervention that keep you going. Just when you're ready to quit, you'll hit a spectacular shot better than you seem capable of making. To me, these random events are a signal that the deity, or deities, like golf.

A PLAYER GETTING READY to play in the 2008 U.S. Mid-Amateur came off Bandon Trails one day. It was cold and windy. He'd shot around 90. "I'm too good to shoot a score like this," he said, shaking the scorecard in my face. I asked him, "If you were a gunfighter instead of a golfer, how good would you be?" He said, "Pretty good." I said, "Do you know what happens to gunfighters who are pretty good?" He got the message. Unless you're a perfect golfer the likes of which we'll never see, you're never going to be so good that you never shoot high scores.

THREE OF THE BEST STUDENTS I've ever had were blind from birth. They had no time frame for improving, no hard-and-fast goals they had to meet or else. Like every other challenge they'd faced, they just moved straight ahead. Not being able to see their bad shots probably helped curb their frustration. But the pace of their improvement was incredible. A month in, they each were better than any beginners I'd ever had.

AFTER I'D BEEN SKIING AWHILE, I asked my ski instructor what I needed to do to get better. He said, "Ski more vertical feet"—meaning I simply needed to ski more, in the way a pilot accumulates hours in the cockpit. When I asked my wife, Janet, the same question, she said, "Ski steeper." That meant skiing faster, making fewer turns and trying more difficult runs. The translation, for golf: Play more, and challenge yourself. Get out with better players and longer hitters.

Pacific Dunes' third green and 13th fairway.

Stephen Szurlej

TO PLAY MORE GOLF, you need to manage your time better. I'm so disorganized that I signed up for a time-management class—for which I was 45 minutes late for the first lesson. The time-management expert told us to divide our lives into three compartments. The first consists of everything you absolutely have to do. The second you must get around to doing eventually. The third is everything else. The secret, he said, is to devote everything to the first two compartments and then ignore the third.

I WAS AT THE 17TH at Pebble Beach when Tom Watson chipped in to win the 1982 U.S. Open. At the time I was the teaching pro at Pasatiempo, and the next day I phoned the Ram golf company to order a couple of those sand wedges. They told me it was a TW 860 model, custom-made for Watson, and not yet in production. I gave them my Visa number and asked them to send me the first two. Boy, was it ever a great wedge. One day, it went missing from my bag. I was devastated. The other pros—there were seven of us at Pasatiempo, including assistants—launched a forensic investigation. We knew whoever took it had to be a good player, so that eliminated a bunch of people. We checked the tee sheets to see who might have been around my bag. They measured some other factors. Finally, they narrowed it down to one guy. One of the pros dialed the phone number of the chief suspect. He said in his most menacing voice into the phone, "You took the wrong guy's wedge," and hung up. It was taking a gamble, but the next day a man showed up with my sand wedge, begging for forgiveness like a man in debt to the mob. It was wonderful to get my wedge back, and I used it for years, but I finally took it out of play because I was afraid it might disappear again.

THE HEAD PRO at Pasatiempo was a guy named Buddy Sullivan. He was an old-school pro, likable but gruff. One day Buddy gathered the assistants together and said, "We're creating a position here called teaching pro, and I'm giving Grant the job. If anybody has a problem with that, I want to hear about it right now. I don't want any bellyaching about it later." There were no objections. Then Buddy took me into his office. "Your No. 1 job is to not make anybody worse. If I get reports about people regressing with their games, you're gone, and the next guy gets your spot." With that hanging over my head, I approached teaching with a sort of Hippocratic Oath: First, do no harm. What I found was, it's possible to make every golfer better, in some department of the game, immediately. If your teacher doesn't help you improve the first lesson, consider seeing someone else.

I SERVED in the Marine Corps and enjoyed most of it. One morning during training at Camp Pendleton, I got very sick. I wasn't sure if it was food poisoning or what, but I felt like I was going to die. You had to ask permission to see a doctor, and I did, almost crawling to the drill instructor. He said, "What's your problem?" I said, "I think I need to see a doctor." He gives me a five-second going-over with his eyes, then said, "You're not sick. Get back in line." For some reason—fear, probably—I immediately felt better. I learned a lot from that. The mind can overcome practically anything.

DURING ONE OF THOSE training stints, they had us do 50 push-ups. When we counted off the push-ups from one to 50, only half the guys could finish. But when we counted backward, from 50 to one, everybody finished. What's the golf analogy? Thinking about your total score along the way can be overwhelming. Your score will be better if you train yourself to focus on one shot and one hole at a time.

YOU'RE BETTER than you think you are. To make the clubhead travel 26 feet on an arc and catch the ball on the clubface is a small miracle. Beating yourself up over the imperfections within that miracle is kind of ridiculous. Never wait to be good to have fun, and never lose sight of the fact you're doing something pretty amazing.

IN MY FREE TIME, I went to college at San Jose State. A phys-ed course was required, and for me it came down to boxing or badminton. I chose boxing. I thought I was doing pretty well at it, until I got into the ring with a guy from Philadelphia. He was a southpaw, and I circled in the wrong direction. He punched me silly. Even boxing has a golf analogy, though. Golfers, like fighters, are going to get hit. The question is, can you learn to circle in the right direction, and somehow soften the blows?

GOLF HAS ONE OF THE SHORTEST execution times of any sport. The swing lasts two seconds. For a 90s-shooter, that comes to three minutes where you're actually hitting the ball. So how are you spending the other four hours and 15 minutes? In my view, it should all be fun. Anything less, and you're probably playing the wrong game.

WE WERE TREKKING IN NEPAL, going along a trail. Our guide says, "Put down your packs, sit down and put your cameras away." Some men suddenly appeared on the trail. They were Tibetan bandits, very large men and some of the toughest people in the world. Our guide was speaking to them when this woman in our group produced her Nikon camera and took a picture of them. Things then got very tense. The bandits got even more agitated, and our guide clearly was begging them for our lives. They let us go, and the guide told us the Tibetans hate having their picture taken, that it steals part of their souls. After we got back to the States, I got a call from the woman. In recounting our adventure, she told me all of the photos she took turned out beautifully except the one she took of the bandits. The image wasn't just fuzzy or overexposed, it was completely black. Strange things happen on this planet. There are forces out there much more powerful than most of us know about.

IN EVERY FOURSOME, one person is always having the most fun. That person might as well be you.

ON THE PRACTICE GREEN, you should occasionally run a 10-footer five feet past the hole—on purpose. Hitting a putt too hard in a match is always a shock to the system. Your body language often expresses that—hands on the hips, rolling your eyes, going through histrionics like you just can't believe it. Opponents feed off that. Hit a putt too hard once in a while and control your body language. Learn to react and think like it's no big deal, that it's something that happens. Practice the inevitable, and believe me, it will save you strokes.

THE 18-HOLE ROUND is an invention. So is the nine-hole round, for that matter. Play whenever the opportunity presents itself, even if it's a couple of holes. Darting onto a course 30 minutes before it gets dark is a great thing. See how many holes you can play before you can't see anymore. Mix up a few holes until you wind up back at the clubhouse. Abbreviated rounds are always an exhilarating surprise.

NEVER BET WITH A STRANGER whose right shoe is chafed on the inside of the toe cap. That guy has a great weight shift, good timing and knows how to get through the ball. He will kick your butt.

ANOTHER PLAYER to avoid betting with is the one who spends a lot of time at the putter rack in the pro shop. Good putters, even if they've used the same putter for 30 years, like putters in general and are always picking them up, hefting them and evaluating. They're generally better under pressure than most people.

ONE GUY I WILL BET WITH is the guy who leaves his clubs in the bag room at the club. I believe in bonding with your clubs—all of them, but your putter especially. My putter goes in the house with me, every night. It makes me inclined to pick it up a couple of times a day. If your putter isn't nearby, there's going to be a disconnect, a slight unfamiliarity, when you do pick it up. It's not a hammer, folks. It's . . . your putter.

RICK BARRY, the NBA Hall of Famer, is one of the strangest and most remarkable competitors I've ever met. Years ago, Rick and I played a $5 nassau against two other players at Pasatiempo. He must have asked me 20 times where the match stood. He was concentrating so hard on executing, he forgot the bookkeeping. On one hole, a par 4, he sailed a shot O.B. and sat on the bench and sulked. I thought he'd quit on me; he wasn't very evolved as a golfer yet. When the three of us got to the green, here came a ball, flying onto the green from the tee. Rick, who had gathered himself, was back in the game. He made the putt for 4, too.

PRACTICING at Makaha Golf Resort one day in 1966, I felt a pair of eyes watching me. I turned, and it was Ken Venturi, who had won the U.S. Open a couple of years earlier. He was over at the club hanging out and watching the golfers. My driver wasn't going anywhere that day. Ken approached, said he liked my swing. He inspected my driver and asked if I wanted to add some distance. He wrote down, on the back of a business card, a list of roughly half a dozen items to pick up from a hardware store. "Meet me back here tomorrow, 9 a.m.," he said. On the list was shellac, sandpaper, wood stain and a couple of other things. He met me promptly, took me inside the shop and completely reworked and refinished my driver. Boy, was it beautiful. After giving it a few days to dry, I took the driver and instantly gained 30 yards.

MY FAVORITE PUTTER isn't exactly a putter anymore. It's an Odyssey 550 putter that, over the years, acquired loft from hitting so many long run-up shots from off the green. Today it's more like a strong-lofted hybrid. I can hit it anywhere from two feet to 200 yards. I haven't measured the loft, but I suppose it's around 12 degrees. It's a novelty I like to show off with, but on the firm turf at Bandon, it's also a bona fide weapon. When I have 150 yards through a strong wind, and there's no greenside bunker to carry, it's absolutely the right club choice.

ALONG THE WAY to getting my black belt in tae kwon do, I learned things that helped me in golf as both player and teacher. One was the importance of simply showing up, of coming to class every time without fail. In golf, you have to avoid staying away from the game for too long. Another was respect for the craft, knowing you had to pay a price to get good. A fellow came into the dojo once and said, "I'd like to get a black belt." The sensei handed him a black belt and said, "That will be $5."The fellow said, "No, I want to become a black belt," to which the sensei replied, "That will be five years." Golf is like that. There are no shortcuts.

I WAS A CONSULTANT on the movie "Golf in the Kingdom," which was shot at Bandon Dunes. I've known the author of the book, Michael Murphy, forever. The most meaningful part of the book is the saying, "Beware the quicksands of perfection." You can go a long way to improving your golf swing, but you have to let a part of it be mysterious. You can't control the whole thing. The body is very intelligent until you try to teach it to be perfect. Then it will rebel. You can work on getting better and give your body some help, but there has to be a little space where you allow your body to be itself.

PLAYING ALONE as a teenager at La Rinconada Country Club in Los Gatos, Calif., I made my first hole-in-one, on the 11th hole. A 7-iron, 140 yards. I was thrilled at first, but then became bummed because there was nobody to share it with. I sat on the tee, waiting for someone to come along and somehow attest my ace. While I waited, I thought I might as well hit another ball. The next shot—and I know this is unbelievable—wrapped itself in the flag, then dropped straight down into the hole. In shock, I sat down again. Then, in a daze, I walked in. What's bothered me about this over the years is the fact that I didn't try a third shot. I want to go back there one day. I hope the tee is set at 140 yards, because you can bet my club selection will be a 7-iron.

JIM WAKEMAN, a good player and a former pro at Bandon, came to me one day and said there were two college kids looking to play a money game. We both were up for that. When I saw the two kids, I immediately became concerned because they were wearing sneakers—I mean, high-top Converses. When I looked in one of their bags and saw an old Billy Baroo putter, I knew Jim and I were going to have our hands full. At Pacific Dunes that day, I saw some of the best team golf of my life. Conditions were tough, and our opponents—these children—were making birdies all over the place. Jim bailed after we were a few holes down. Me, I pressed after every birdie they made. It became sort of like high-stakes poker, where you think the cards have got to start coming your way. Sometimes you have to give in to the temptation to do that. But they never did cool off. The Converse kids shot 13 under. I lost a few hundred, way too much money. But the golf I saw that day made it worth every penny.

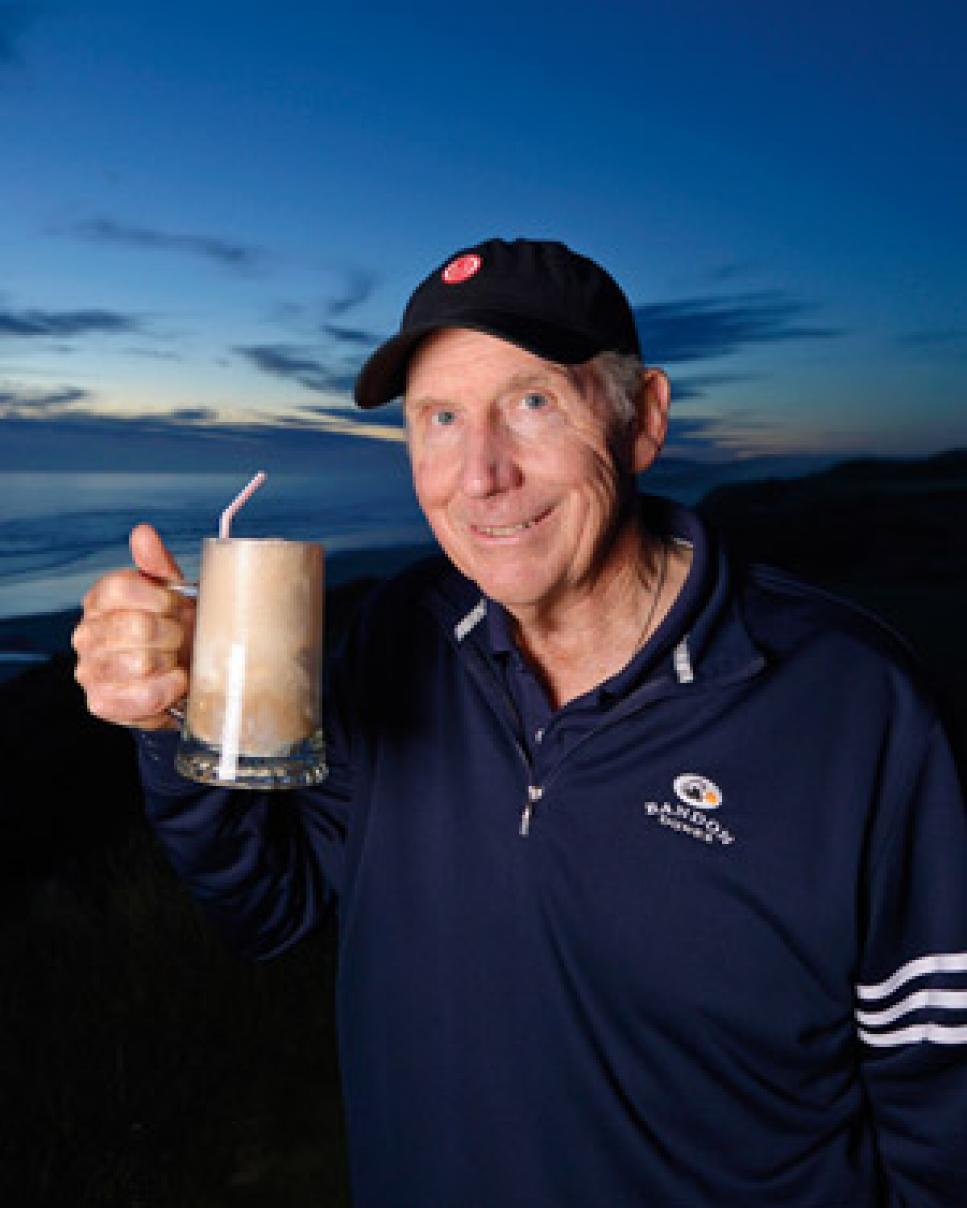

WHEN I WIN A MODEST BET against someone who enjoys drinking beer afterward, I don't order anything with alcohol when we go inside to settle up. I order a root-beer float. I can't tell you how irritating this is to guys who like a couple of beers and expect you to have a couple, too. I make noises with the straw, smack my lips a little, hold the glass with both hands like a little kid. First they roll their eyes. Then they look a little disgusted. Finally they get glum. When we play the next time, there is no easier victim. The thought of losing to a root-beer-float drinker makes them try too hard.

A YOUNG MAN I knew, a good golfer and a very good athlete, was in a motorcycle accident and shattered his left leg. When he tried to resume playing golf, it just didn't work. This guy couldn't withstand any sudden increase of weight. I was the fifth pro he saw, hoping to find a way to swing the club without collapsing in pain. After watching him make one swing, I went into the shop, brought out a left-handed 5-iron, teed a ball and told him to swing from the other side of the ball. Because he was a good athlete, his first shot flew 130 yards. He started with his weight forward and, camping out on that right leg, resumed playing the game. In golf there's always a way.

I LOVE A STORY I heard about Davis Love Jr., father to Davis Love III. Harvey Penick was watching Love give a lesson and saw him getting a little impatient with his pupil. After the lesson, Mr. Penick instructed Love to rent a musical instrument and sign up for lessons. Love did this—he chose the clarinet—and for a couple of months struggled to play the most rudimentary tune. Love came back to Penick and told him, "I get your point." From then on, he had much more empathy for what a golf student goes through. Remember that next time you offer swing help to your child or spouse.

HERE'S WHAT I WANT IT TO BE LIKE at the end. I'm 150 years old and trudging onto the 18th green. I'm the only player on the course. It's cold, raining hard, and about to get dark. A bunch of people are looking out from a large window at the clubhouse, marveling that anyone would be playing in those conditions. One guy nudges another and says, "You see that old man?" The fellow answers, "Yeah, what about him?" And the first guy says, "Don't play him for money."

I TOOK ON A STUDENT whose favorite word was "bad." He was always hissing to himself, "You're so bad," or "That was such a bad shot." Before our second playing lesson I told him I was going to fine him $10 every time he said the word "bad." Throughout the round he struggled to contain himself. I egged him on a little—"Go ahead, say it. I need the money," I told him. But he didn't say it, and toward the end of the round he started to play very well. His wife, of all people, sent me an email a month later thanking me for helping him not beat himself up so much. "He's been nicer to me, too," she wrote.

I WAS IN THE LODGE at Bandon Dunes one day, commiserating with a good player who'd just shot a terrible score. He was going on about how bad his game was. An older woman, sitting alone at the table next to ours and within earshot, apparently had heard enough. She came over and said, "You don't play golf because you're good, you play because you can." The man started to answer her but just sat there, looking more humble by the second. Finally he said, "Thanks, ma'am. I needed that."

THE PRACTICE PUTTING GREEN at Bandon is more than an acre. I'm out there when a guest came over and said, "Are you the guy who can putt with a sand wedge?" I say, "That's the rumor." He says, "Tell you what: If you can hole it from here to that cup over there in one try"—and he points to a hole clear across the green—"I'll give you X amount of money." I won't say how much, but it had a lot of zeroes on it. I threw down a ball and whacked it with my wedge. When the ball got about 10 feet from the hole, he says, "Oh … my God." And of course, the ball goes in. He was horrified; it was a lot of money. I handed him my business card, and a couple of weeks later a check lands in the mail, along with a scrawled note that was unreadable. The vibe told me he was upset. I never cashed the check, but I kept it in a drawer as a souvenir. Janet stumbled across it one day. She wanted to know what it was about, and when I told her the story, she just shook her head.