News

Jake's World

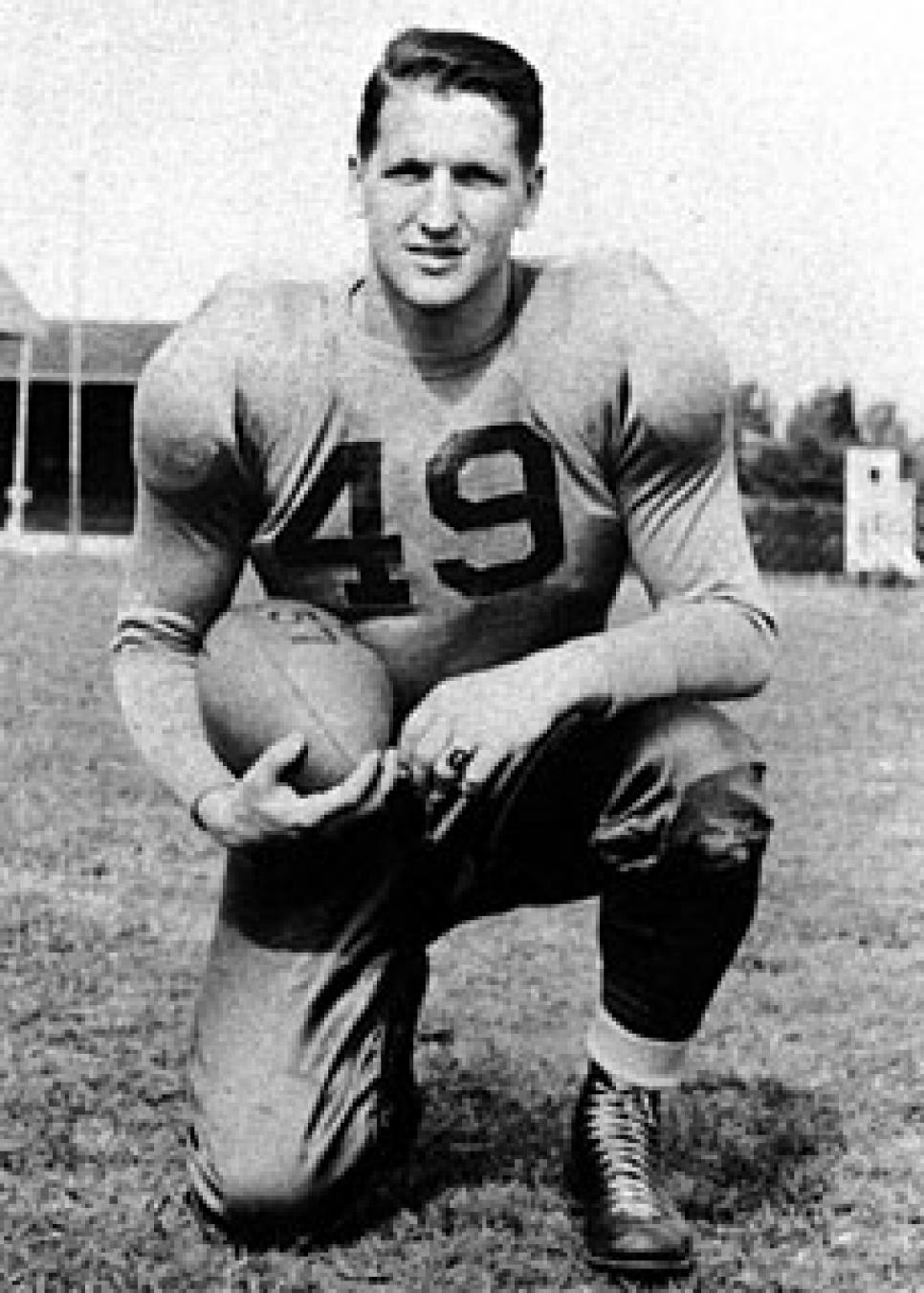

A gentleman but not always a gentle man, Peter Jacobsen's dad, Erling, was one tough Oregon Duck as a young man.

The fat brown football hung in the cool autumn sky. Eleven Ducks held it in their gaze as they ran down the field, not an easy thing to do, because an equal number of Rams were attempting to knock the quackers on their asses and practically all the thousands of fans in the stadium wanted them to do exactly that. This was a home game for Fordham, at the Polo Grounds in the Bronx, New York City, Saturday afternoon, Oct. 15, 1938. The Rams were beasts in the East; they had been undefeated in '37 and would drop only one game in '38. The boys from the University of Oregon, on the other hand, lost about as many as they won. But they looked vivid in their white jerseys with green numerals over emerald pants. The white pattern painted on their leather helmets resembled headphones or earmuffs. Fordham wore maroon.

As the punted ball tumbled down from its apogee, its potential receiver extended his right arm and waved, a gesture indicating his wish to catch the thing unmolested in return for a promise to not advance after he caught it. But one running Duck, number 49, missed or ignored the white flag, and he leveled the Fordham man with such extreme prejudice that spectators gasped before they started to boo. Referees immediately threw Erling Jacobsen out of the game.

Fordham won, 26-0. The momentarily disgraced football player boarded a train with his teammates for the long slow ride back to Oregon. He'd traveled from one coast to the other and back for a football game in which he lasted only four plays. What manner of man would he become? The verdict among his friends and family 50-odd years later would be surprisingly unanimous. Erling Eugene Jacobsen was a gentleman but not a gentle man, simultaneously fierce and funny, stoic and strict. A caddie as a kid, he held out golf to his wife and children as a suitable activity, and he guided the project along until their cumulative handicap was 27, a microscopic number for a family of six. Despite the most severe provocations, he never complained, and he couldn't tolerate those who did. He was a stickler regarding rules and comportment and had a complementary and frequently expressed disdain for golf carts and for the wimps who would ride in them. He taught his kids by the hour and they won tournaments by the score, but he almost never watched them in competition.

A moment: Erling came to breakfast dressed for work one morning and observed his two college-aged sons at the table digging into bowls of corn flakes. "What the hell are you doing here?" he asked. "We're playing in the Oregon Open," they explained. "It started yesterday." Father snapped open the sports page and observed a headline: Jacobsen's 68 leads Open. "Maybe you should withdraw and go back to Eugene," he said to the tournament leader, Peter, and to his oldest son, David, who'd shot a few more than his brother. "You boys need to focus on your studies."

"I knew Erling since the late '40s," says Tom Edlefsen. "A character. Jesus. A firecracker. A very positive man but not flexible at all; there was no difference of opinion with him. He was tough with those kids. Tough love, although that was a term we never used. He insisted they do it right.

"He could be difficult as hell. When I was president of the club, he became unhappy with some trivial thing—a branch was trimmed incorrectly or something—so he asked me, 'Did you have anything to do with this?' And I said, 'I guess so, I'm the president.' He said, 'Then you should resign.' He and his brother Leif, they were Vikings, believe me. He was a damn good man."

If you don't look too closely, the incidents and accidents around the gruff but benign patriarch seem like fodder for a television sitcom. His wife and golf tournament-winning kids loved him, and indulged him. Their conflicts could easily be portrayed as mild and comedic, set at the country club, and resolved in half an hour. "Wow," he said, observing his daughter on the practice tee once. "Someone's gained some weight." Consciousness-raising on what puberty does to girls' hips—that could be an episode. He was a prankster: While on vacation, he used breadcrumbs to lure a couple of geese into his sons' bedroom to wake them up. The birds accomplished their mission, but it was messy. He was a disciplinarian: When teenaged Peter threw a club and uttered several magic words that we'd have to bleep, Erling ordered him off the golf course. Peter couldn't wait in the clubhouse and have everyone ask him what was going on, so he sat in the car for an hour or two, muttering and alone with his thoughts. That's a show. And there'd be some laughs in this golf dad's wonderful lack of awareness of popular culture. Once he was invited to walk inside the ropes at a celebrity pro-am, the better to mingle with his son Peter and Clint Eastwood. "So, Clint," he said, shaking the actor's hand. "What do you do?" But Erling's journey was far too complex for a sitcom, and although it was frequently fun, it wasn't really funny. Life eventually hit him with its very worst. He became the guy getting clobbered when all he wanted was a fair catch.

The short silver prop plane zoomed through smoke and boiling air. As anti-aircraft fire popped and pinged into its wings, the pilot felt an irresistible desire to fly higher above the guns on Truk or Okinawa or Formosa, but he couldn't get high and stay there, not if he wanted to do his job. The Curtiss SB2C Scout, a dive-bomber, crew of two, held a thousand-pound bomb in its fuselage and smaller bombs under each wing. Pilot in front, gunner-navigator in the rear, both encased in a clear eggshell that allowed them to see and be seen. The "Helldiver" had to get ridiculously low—about 1,200 feet—to be effective. Erling Eugene Jacobsen flew from, and landed on, a carrier called the USS Intrepid.

Roller-coaster ascents and descents … the time he broke his neck in a crash landing, and the resultant year in traction … death. What stories Erling could tell! He didn't tell them. The navy flyboy returned to Portland to marry Barbara Patterson, a pretty girl who liked to laugh as much as he liked to keep his mouth shut. To be sure, part of his warrior's reticence was genetic. "How can you tell an outgoing Norwegian?" jokes David Jacobsen. "When he talks, he looks at your shoes." Erling was Norsk through and through; his parents met on the immigrant ship from Oslo to Ellis Island. Marie, his mor, was from Bergen, and would never learn much English. His far, Julius, the son of a fisherman from a northern fishing village, would himself be a fisherman and a longshoreman in the port of Portland, Oregon. The milestones in his life are easily told: Jefferson High; a football scholarship to the U of O; a bit of pro football in Los Angeles in which he got a broken nose from a knee in the face; war; marriage. Four kids: David, Peter, Paul and Susan. Far assigned the nicknames: Fobber (David's early attempt at "Father"), FB (Fat Butt), Pupper (Paul's favorite stuffed toy animal was a puppy), and Princess Bubbles. David and Paul resembled their father and inherited some of his reserved style. Peter and Susan replicated their mother's good looks and champagne-bubble personality.

Erling made golf the center of family life and put himself at the center of the golf. He kept it fun, and he made it more or less optional. "I'm going to the club," he'd say. "Anyone want to go?" If Erling's kids were going to play they were going to do it right, but the very idea of him insisting that one of them hit more practice balls causes David and Susie to smile and shake their heads. On days they didn't have basketball practice, David and Peter took a city bus after school, transferred to another bus, hopped a fence, then walked along a railroad track to Waverley and Dad. Of the four kids, Paul was the only one not totally smitten with the game.

Which must have been a conflict: The Jacobsen children (except Paul) won tournaments right and left, and father evangelized with anyone who'd listen, especially new members, juniors, beginners, and the kids pushing greens mowers and raking bunkers. He preached for playing by the rules, and against golf carts and the concomitant evil of cart paths, which he believed defaced the playing surface. Beneath the vaulted ceiling in the living room, his kids swung clubs and he critiqued their action. His mantras on the practice tee and in the house were "Go back slow and turn your shoulders" and "Use your big muscles." Post-round, his ritual questions were "Did you have fun?" and "What did you learn out there?" He believed in discipline; he did not believe in praise. "He'd never tell ya, 'Nice going,' " Peter recalls.

"One of the big things he taught us was that life isn't always fair, and neither is golf," Susan says. "You can hit a perfect drive and your ball might hit a sprinkler head and go out-of-bounds." When his kids achieved a certain level of competence with the playing part of the game, Erling stuck them in his weekend foursome, then watched them like a hawk for errors in manners or procedure, because there was way more to know than just the order of play.

Barbara, a beginner when she married, won the Waverley club championship. David, the oldest Jacobsen child, was, is, a hell of a player. He made the University of Oregon golf team and qualified for the U.S. Amateur. He tried to qualify for the tour a couple of times, and almost made it once. One year he reached the semifinals of the U.S. Mid-Amateur. Susan, a superb athlete, played in four national championships as a teenager and got to the semifinals of the Oregon Women's Amateur at age 15.

Peter outshone them all, of course. He made the tour on his first try and won big professional events and lots of money. Like his father, he was cool under pressure, and his bright personality—a gift from mom—attracted other stars, such as Jack Lemmon and Arnold Palmer. Like his friend Arnie, Peter had the very pleasing habit of granting respect to anyone he met, making strangers holding a Sharpie and a program feel they were at least as important as he was. Peter Jacobsen earned his success with hard work and handled it with grace. His sibs had to adjust. They weren't just themselves anymore, they were … "We're very proud of Peter, and, really, the negatives have been so minimal," says Susan. "But I'm always introduced as 'Peter Jacobsen's sister,' as if I'm not smart enough or cute enough or funny enough to just be Susie. It's 'can you get me a book, can you get me a ticket, why did he miss that putt, can you get him to speak to our Rotary, and what does he think about Tiger?'"

As Peter's star rose higher, his younger brother receded from view.

Paul broke with the two main Jacobsen traditions. While golf preoccupied the rest of the family, Paul got down to an 8— good but far from great—then slowly drifted from the game. "No question—he didn't want to be out there [on the golf course]," says Peter Walsh, a close family friend. "He was expected to be out there." And he was expected to follow the path of his father, Uncle Leif, and brothers David and Peter to the University of Oregon and the Kappa Sigma house, but after high school Paul set off for the wilds of Los Angeles and Occidental College. He had to get away. He felt stifled.

"When Paul stopped playing golf, it was like permission for me to do something else," recalls Susan, the final Jacobsen to reach the post–high school crossroads. "It was, 'Oh, it's OK for me not to be interested in this.'" But Susan's disenchantment was a much bigger thing than Paul's. David thinks she had more talent and potential than anyone in the family, and lots of college golf coaches might have agreed. Among those offering scholarships were Arizona State, Oregon State and—cue the fight song—the University of Oregon. She turned them all down. Like Paul, she chose a little school in a big place over a big school in a little place, enrolling at Pitzer in Claremont, Calif., a liberal arts college 35 miles east of L.A. She played lacrosse, not golf, and had plenty of opportunities to hang with Paul, the sibling to whom she felt closest. Erling was not pleased with this turn of events—he nicknamed Susie's new school Armpit Normal—but what could he do? He had problems of his own. Barbara wanted a divorce.

A moment: Bored with the drinking and small talk at his oldest son's July 1978 wedding reception—held, inevitably, at Waverley—Erling slipped out. The father of the groom walked to the golf shop in his good blue suit, got a club and a bucket of balls, and began caressing 5-iron shots out onto the soft green ground of the practice range, a former polo field. Barbara was furious. Ditching his own party was so … Erling. Soon after this incident, she moved out.

Person A in a family of six has a relationship with the other five, and those five have a unique interaction back to A. That's six times 10. Add the temporary alliances that form in any group and family mathematics can make you crazy. For a while, it seemed that Erling, David and Peter were in one camp and Barbara, Paul and Susan were in another. Everyone in the family felt pain from the split at the top, but the separation and divorce knocked Erling for a loop. Then he got sick. There was some speculation that the cleaning solvents they used on board the Intrepid (or the USS Enterprise, the other carrier he served on) led to the cancer in his mouth. But once you've got it, the cause is moot; you've got to get rid of the active cells. Surgeons cut out most of his tongue. It seemed like one of those ironic punishments, like Monet going blind or Beethoven losing his hearing, because, on some topics, with some people, Erling could talk for hours. Around this time, in the mid-to-late '80s, the problems of his youngest son came to a head. Peter wrote about it in his book *Buried Lies: *

… there was a certain tension between Paul and the rest of the family that wouldn't go away. When Jan and I would go to Los Angeles each year for the L.A. Open, it seemed that Paul was usually too busy to come out to the course to watch me play. It was his way of telling me that his life was more important than coming to a golf tournament. About 10 years ago, when Paul was 26, he just blurted out something in a phone conversation with me. "You know I'm gay, don't you?" he said. I told him that of course I knew, and it was no big deal to me.

Paul was depressed, and he used a lot of cocaine and vodka, a horrid combination. But from rock bottom his life advanced in three giant steps: intervention, Betty Ford and sobriety. "You've really come to a good place", David told him. "How did you do it?" "I forgave myself," Paul replied. Then acquired immune deficiency syndrome undid all his progress, undid everything. Everyone in the family went to see Paul in his hospital room in Los Angeles, and everyone's heart broke when they saw how pale and thin their brother and son looked beneath the tangle of feeding and respiration tubes. And the fear in his eyes: "Peter, you can do anything," Paul wrote on a pad. "Please make this go away." He died a few days later. He was 32. His death felt so intensely sad it was bizarre, David said.

Peter wrote that Paul's spirit had visited him at the exact moment of his death, at 1:30 in the morning, Sept. 5, 1988. Barbara and the three surviving kids talked about their loss with those closest to them—Barbara had re-married—and with each other. But how would Erling, without a wife, or a publisher, or the ability to speak—express his grief? He spoke anyway. They held Paul's memorial service at Trinity Episcopal Church in Portland. Susie felt surreal, not really in her body, as she eulogized her brother. She read something or other from Corinthians through tears that made it hard to see the page. Erling's turn. He walked up eight wide, wooden steps to the carved white podium. He looked out into the vastness of the cathedral. Behind him, high above the altar, light shone through a circular, mostly blue, stained-glass window. The father spoke very slowly, making a tremendous effort to be understood. His theme was the New Testament parable of the prodigal son, who leaves, squanders his inheritance, but comes back, and all is forgiven.

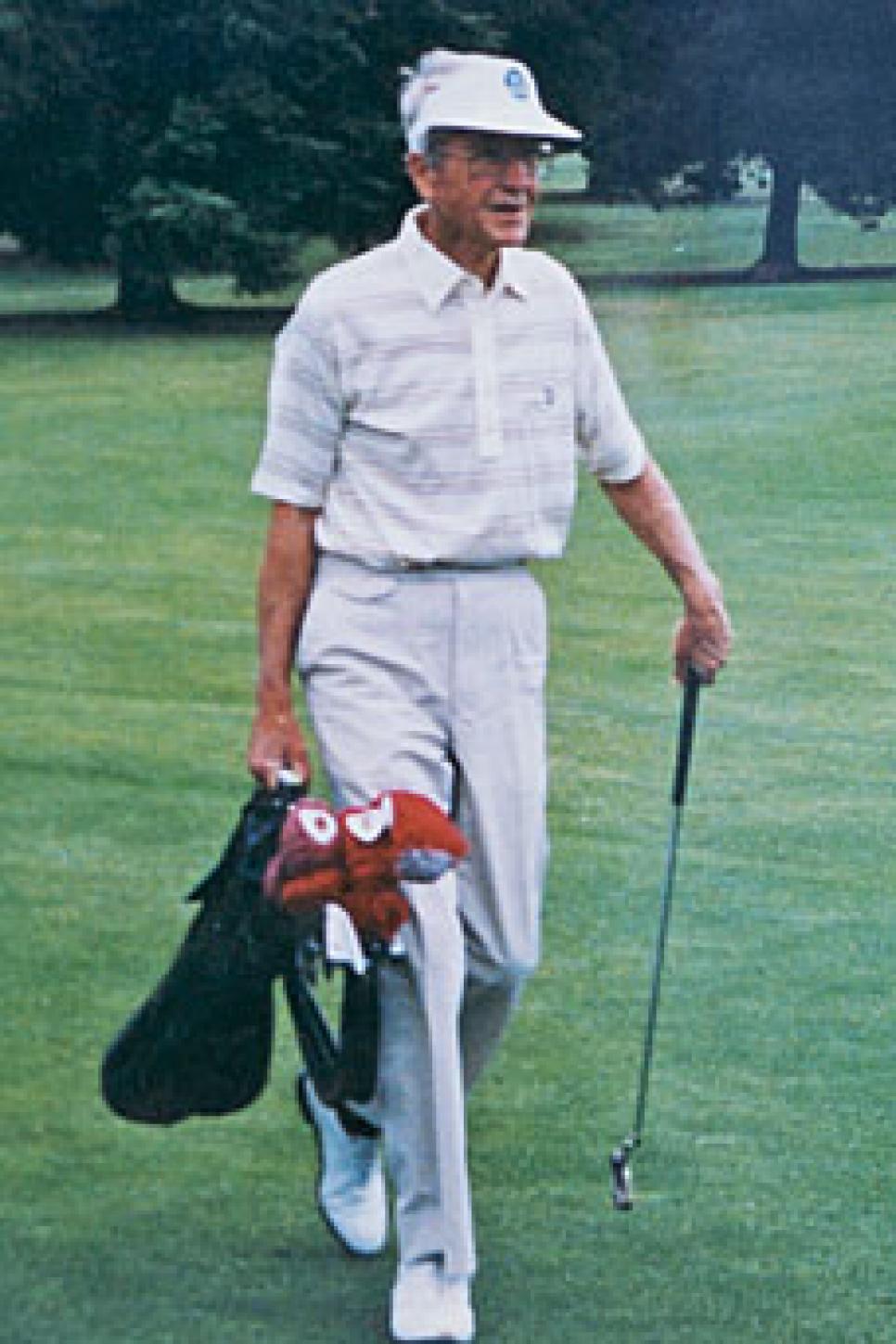

Bucky Sheffield and Erling played Waverley CC every Saturday at noon in any weather from July '87 until April '92. An odd couple: Bucky was a burly old boy (actually, young man) from Lubbock, a wheat trader with the gift of gab and a big golf game. Erling was now a gray eminence with an ear-to-ear scar and a way of speaking that not everyone could get. "I spoke West Texan," Sheffield says. "I had no trouble understanding him." But the older man was losing weight, and though he still carried his clubs, he walked more slowly than before. He had relearned to swallow, eat and talk, but cancer had returned, to his colon. It was killing him.

"I was away from my own father, and Erling was a great mentor, a real man's man," says Sheffield. "Tougher than nails. A war hero. An inspira- tional guy. He never complained about anything and hated people who did. One time I spun a ball off the sixth green and started moaning about it. He says, 'You've been playing here how many goddamned years, and you never noticed that this green slopes?' He never bragged about his sons' golf games, but he certainly defended them. I remember the time he saw Fred Stickel, the publisher of the Oregonian, right after his paper had printed negative stories about Peter. Erling goes up to him and says, 'If you write one more bad story about my family, I'm gonna beat the s--- out of you.'

"By that time," says Sheffield, "he was really sick and weighed about 135 pounds. But still trying to play, and still wouldn't ride in a cart. Sometimes I'd carry his clubs up a hill. That would piss him off." Susan was going through a divorce as the '90s began, so it seemed to make sense to go home and take care of her ailing father. Home: Erling didn't leave the original family house after the divorce; he loved his yard and neighbors only slightly less than he loved his kids and golf. "I asked myself, what is this, 'On Golden Pond?' " Susan recalls. "Are we mad at each other?" They weren't, or weren't any longer.

"My dad was totally, completely humbled by it all," David says. Near the end, he and Peter moved back into their old bedroom, sleeping in the extra-long twin beds there. "Dad and I talked for hours and became dear friends. I learned more about him and about myself than I ever could have if it had all been smooth sailing."

Everyone in the family noticed the new Erling. "I had been uneasy with both his parents at first," recalls Jan Davis Jacobsen, Peter's wife. "But then he made an abrupt change, completely an about-face, and in a very short time. I think it was from Barbara leaving him, not the cancer. There was this softening of the shell he'd always worn. He said to me, 'I didn't understand we had problems.' I said, 'You know, that may be the problem.'

"I remember once, when I was pregnant with Mickey, feeling sick, and Peter was out of town. Erling called, and I mentioned I wasn't feeling very well. He was there in 15 minutes, saying 'You go upstairs and lie down, I'll watch the girls.' I found out later that that was the day he'd been told he had cancer." He died on a hot day. He'd played golf until two months before his death. Susan typed a few words on the old Royal in her father's house and read them at the memorial service:

My first vivid memory of my father's love was during the Columbus Day storm of 1962. If you've been to the house—imagine the power of the wind that day at the highest elevation in town. While Mom took my brothers down to the basement, Dad grabbed me and we climbed into the fireplace. He held me so close I could hardly breathe. I was just shy of 4 years old. At dark times of my life I want to be back there in the cinders during the storm of the century, unquestionably safe and protected in my father's arms … Dad gave me so much more than a great golf swing. I love him and I'll miss him.

At the reception after the service, a little old man named John Carney summoned a son of Erling to come sit close because he had a story to tell—the football story. Peter Jacobsen had never heard it before, and his eyes widened in amazement. His dad had been such a tough son of a bitch. And such a nice man.