How Healthy Is Our Game?

The overall golf economy--including equipment sales and golf tourism--has never been larger.

Hank Haney is most famous for his prominent role as Tiger Woods' teacher, but long before he started working with the world's No. 1 player -- and charging $500 for an hour lesson -- Haney was a shrewd golf businessman.

Starting with a ranch he bought from World War II hero Audie Murphy in 1991, Haney expanded that McKinney, Tex., range into seven practice facilities and three golf courses across the state.

Seventeen years later, despite a struggling economy, the most famous athlete in the world is a professional golfer (and a $100 million Nike Golf endorsee), PGA Tour purses are at all-time highs, the largest equipment manufacturers are reporting record sales, and industry groups are noting that the overall golf "economy" -- including equipment sales, golf tourism and golf course real-estate development -- has never been larger.

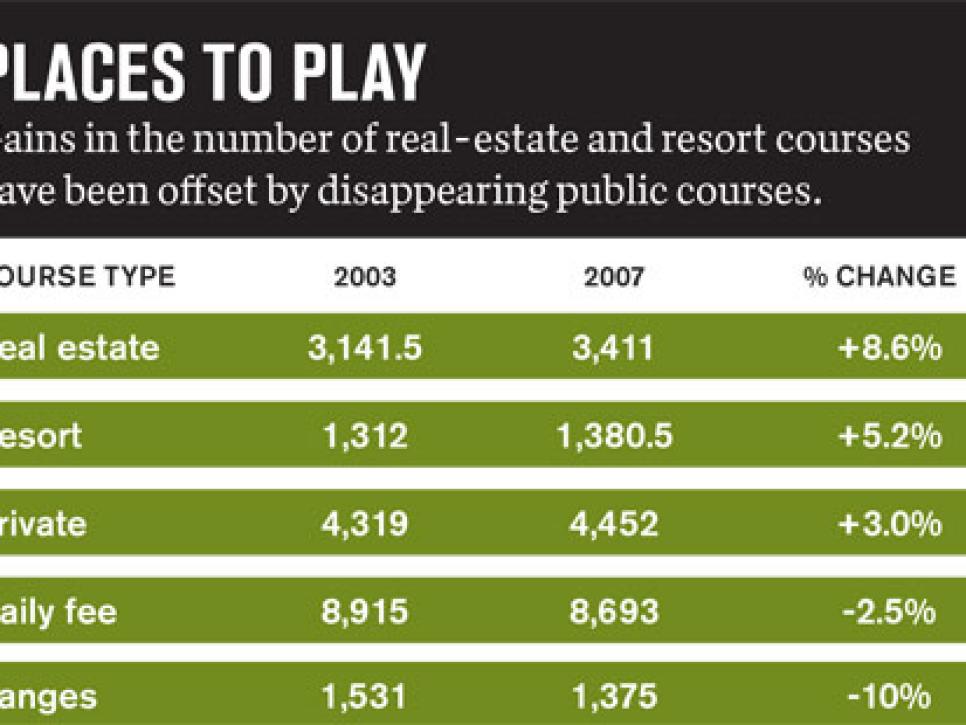

But many people affiliated with the golf industry aren't celebrating. A series of studies shows that rounds played are flat or declining. Television ratings for PGA Tour events are only level. Traditional hot spots for vacation golf activity like Myrtle Beach and northern Michigan have seen a raft of course closures -- either from a lack of play or because of the tough business credit climate. Even Haney's flagship golf ranch became a more enticing business proposition as a real-estate play than it was as a driving range, and he sold to developers.

So is the patient sick or healthy?

Many of the recent participation surveys undertaken by the National Golf Foundation, the National Sporting Goods Association and the industry consortium Golf 20/20 are less than comprehensive or cover only a period up to 2005. So, in spring 2008 Golf Digest and BusinessWeek commissioned Longitudes Group, an Omaha-based research and marketing company, to take the current temperature of the golf industry by exhaustively analyzing market supply trends and geo-demographic data.

The resulting picture of the industry -- a mix of Longitudes' research and the existing surveys and economic data -- is a complicated one. Interest in the game among sports fans and kids has never been greater. But a combination of a weak economy, a September 11-related travel hangover and fiercer competition for consumers' time and entertainment dollars has crunched margins at resorts, mid-range country clubs, small retail stores and daily-fee courses.

The most-cited partipation surveys show a game that's at best treading water and might be dipping under. The National Sporting Goods Association's 2008 survey shows golf's player pool shrank 7.3 percent from 2003 to 2007. The National Golf Foundation's latest report shows rounds played are down 3.5 percent for the first quarter of 2008 and basically flat since 2005. It also shows the number of core golfers has declined.

Longitudes' research includes information from its database of six million golfers, analysis of golf-facility supply and demand, and interviews with hundreds of private-club and thousands of public-course managers nationwide. The group studied the relationship between the supply of public courses in the 27 largest markets across the country and the green fees at those courses, and compared the changes in green fees over the last five years to changes in the Consumer Price Index.

This sophisticated research shows that course operators are facing problems more complicated than just a reduced flow of customers. Courses' peak fees have gone up at the same rate as inflation, but off-peak rates -- which account for a majority of the rounds played -- increased 33 percent more than the CPI. In other words, prices have risen even in the face of flat or reduced demand. That doesn't bode well for attracting new and younger golfers in a weak economy. "Energy costs are going up, and the cost of fertilizer has doubled in the last two years," says Longitudes President Sara Killeen. "Course operators had to raise rates or go under -- and the number of daily-fee courses has dropped 2.5 percent in five years. They're feeling it from all sides. The successful ones are working very hard on their business 365 days a year and managing the details very astutely."

But like a teacher assessing a tour player's round more by how he hit the ball than the number on the scorecard, some industry insiders say the negative participation trends and business forecasts don't tell the full story.

"We do a pretty good job keeping score both on and off the course in the golf industry," says Joe Steranka, CEO of the PGA of America, which represents 28,000 club professionals. "Our figures tell us participation is up 2 percent [NGF, 2000 to 2006], and we've had real economic growth in the game. We went from a $62 billion industry in 2000 to $76 billion in 2005. We've grown from a boutique industry to a real industry."

Although surveys like the ones done by Longitudes and Golf 20/20 -- a group that includes the PGA, PGA Tour, LPGA Tour and USGA -- are consumer samples or estimates of market size, net sales figures from the major manufacturers reflect the total of real merchandise changing hands. Callaway sold $912 million in clubs in 2007, a 13 percent improvement over 2006 and its most ever. Fortune Brands' golf division, which includes Titleist, FootJoy, Cobra and Pinnacle, moved $1.4 billion in equipment, a 7-percent increase over the year before. Callaway reported record first-quarter net sales of $366.5 million, a 9.5-percent increase over the $334.6 million in sales for the same period last year. Fewer players might have played fewer rounds, but $500 FT-i drivers and $46 boxes of ProV1s were still being sold.

The biggest change has come in how players are buying that equipment, says Leigh Bader, who has been in the equipment-retail business since the early 1970s, first at the store he co-owns in South Easton, Mass., Joe & Leigh's Discount Golf Pro Shop, and now online at 3Balls.com. "The numbers are telling the story that dollar sales are up, but in our store, the numbers have leveled off," says Bader. "You could walk out my door and go to any one of 13 Dick's Sporting Goods and buy equipment. That's put a lot of independents out of business. We consider it a victory that we've survived."

In the same way the equipment manufacturing business is distilling to the four or five largest companies -- Callaway, Titleist, TaylorMade and Nike accounted for 65 percent, or $4.1 billion, of total golf equipment sales in 2007 -- small retailers are being pushed out by big-box stores like Dick's and mega-retailer Edwin Watts. According to Longitudes' retail data, the number of off-course retail locations has shrunk by a staggering 25 percent in the last five years. But the square-footage devoted to retail golf equipment sales has increased by 7 percent over the same period.

A growing -- and harder to measure -- piece of the equipment pie is the used-club market, flourishing online through auction sites like eBay. "I see our brick-and-mortar business staying healthy, though not trending up, but online sales and the secondary market are very promising," says Bader, whose online used-equipment store sells more clubs on eBay -- 400,000 last year -- than anyone. "We're all chasing the same core group of avid players, but so much of golf is consumables -- things like balls -- and that's a function of rounds played. I've never seen a cycle like this one."

Industry experts joust about the validity of participation survey results -- and even the golf business' overall prognosis -- but they agree on one major point: The game needs to find more players and encourage them to stick with a sport that can seem daunting for beginners.

"If you go back and read state-of-the-game stories from the 1920s, 1940s and 1960s, they have the same industry focus," says Steranka. "Time, money and skill are still the barriers to entering this game. We asked people to rate what the most important element of the golf experience was in terms of enjoying it, and it's hitting good shots."

To that end, the PGA started its Play Golf America program in 2004. One aspect of the initiative connects potential players with teachers through its Free 10-minute Lesson Program (started by Golf Digest and the PGA), with hopes that they develop a long-term interest in the sport. "When we track the people who come in for a free lesson, 30 percent are new customers to the facility," says Steranka. "Each of those facilities that participates ends up getting a $2,400 lift from the program, in terms of what those people spend on green fees, lessons or equipment."

The First Tee program has introduced the game to millions of kids since 2000 (see below), and CEO Joe Louis Barrow Jr. believes the same kind of initiative could work to bring adults to the sport. "I'd partner with the 16,000 golf courses out there to offer a set program for adults to learn the game and develop a love for it," says Barrow. "We found that if you introduce people to the game in a set curriculum, then ask them to come back with people they learned with, they push through that learning barrier that exists at the start."

If the recruitment drives are successful and more people take up the game, it won't be as easy to get a tee time as it has been over the last five years. That might be a good problem to have, but it's still a significant one for a sport that has an established -- and parochial -- player population. Many of those players don't look at empty golf courses -- or reduced initiation fees at country clubs -- with the same concern club managers do.

"Golf is not beginner-friendly," says Haney, who is spending more time at his International Junior Golf Academy in Hilton Head. "Everything is designed for people who already play. Juniors are a noble cause. But what we need are 50- and 60-year-olds to get into it, because they're real, live consumers. They have an interest in playing, but nobody's making it easier for them."

How well the industry makes those aging boomers feel welcome will define the game's next five-year phase. Fail, and it's a long wait -- and more course closings -- before that generation of juniors Haney mentions get their own checking accounts.

[Ljava.lang.String;@4260690a

Elementary, My Dear

The First Tee hopes to draw kids to golf in gym class

Golf organizations and manufacturers have spent millions to draw young people to the game -- and create the next generation of equipment buyers, green-fee payers and country-club joiners. But it might be elementary school gym class that finally changes the math.

The First Tee, a nonprofit organization devoted to introducing the game to kids, is ramping up its National School Program -- an initiative that will incorporate golf into the basic physical-education programs at elementary schools nationwide.

More than 2,000 schools have signed up for the program -- which costs $2,800 per school for equipment and teacher training in the basics of golf instruction, rules and etiquette.

"We want to be where the kids are," says First Tee CEO Joe Louis Barrow Jr. "One of the broad challenges facing the sport is that it's elective. Unlike going outside and tossing a baseball or shooting baskets, you've got to make a commitment to play golf. The National School Program is building a platform to reach more than three million kids. They're exposed to us. I think a strong interest in the game is going to manifest itself."

More than 300 schools are on a waiting list to get the program, which uses kid-friendly clubs with large heads and oversize balls that attach to a Velcro-covered flagstick. The grips on the clubs are pentagon-shaped, with reminder dots to show the correct hand location, and every shot is hit from a rubberized tee and mat that helps a player's alignment.

The golf component was designed to fit seamlessly into the standard phys-ed curriculum developed by the National Association for Sport & Physical Education. Kids get multi-week exposure to basic golf movements, rules and etiquette, just as they do in basketball or kickball.

Count the kids who are projected to be introduced to the game through the National School Program -- 3.5 to 4 million in 4,000 schools by 2010 -- with the 1.2 million who already participate in programs at The First Tee's 202 chapters and 547 learning facilities nationwide, and it's easy to see why Barrow is more optimistic than many about the sport's future.

"We're building a generation of players who are going to contribute a tremendous amount to the golf economy," Barrow says. -- Matthew Rudy