Grunge and sponge

The orange of alma mater Oklahoma State comes out in Mahan's attire (here, the shoes).

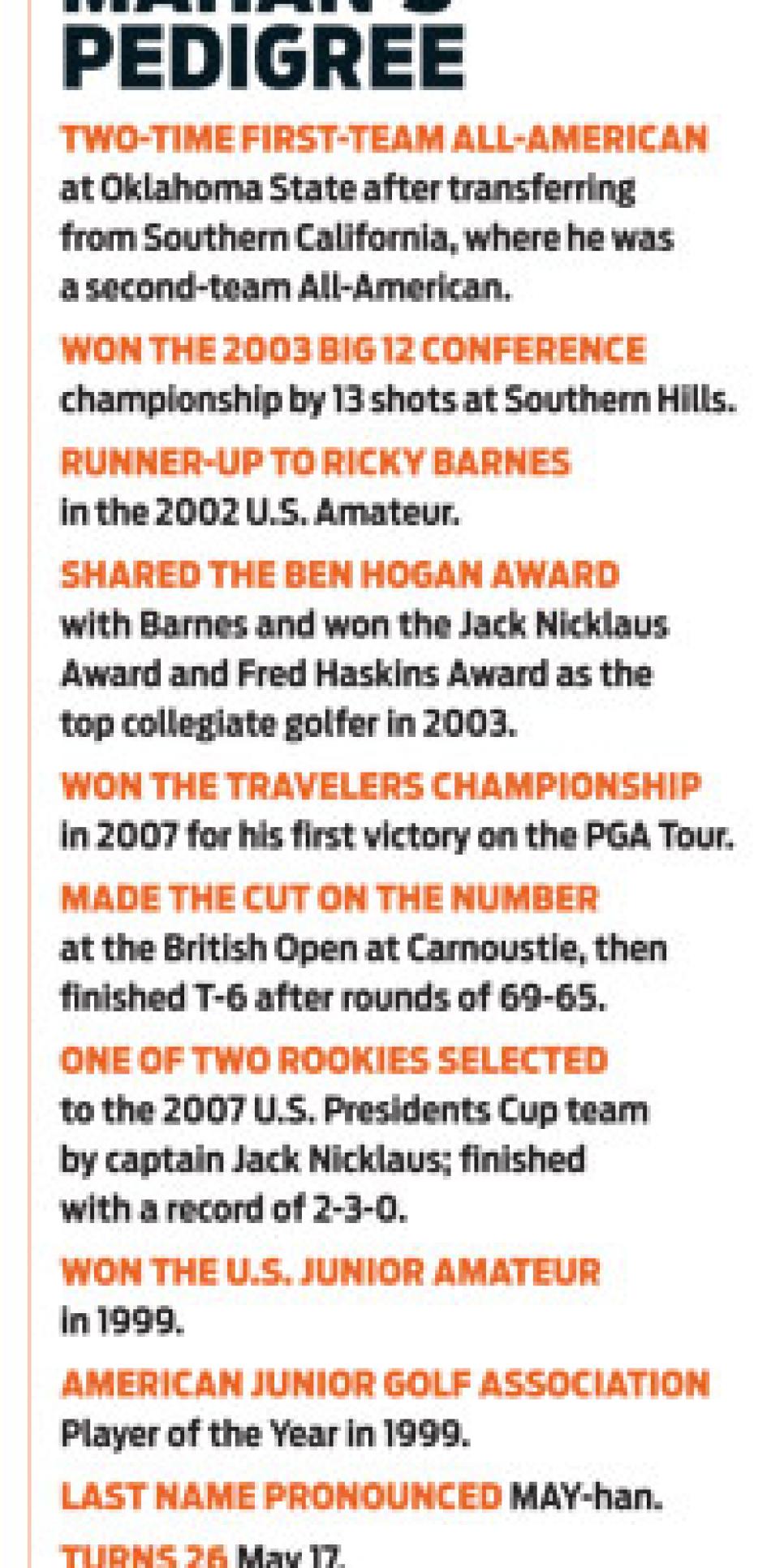

To the traditional golf crowd, Hunter Mahan borders on disheveled. The tousled blond locks, wispy facial hair and slightly avant-garde fairway fashion sense present him as a sort of semi-chic slacker. Adding to the impression is a sleepy surfer manner, probably not dissimilar to the one his dad affected in his days as an undercover drug cop working South Central for the LAPD. But Mahan, 26 years old in May, is a member of the hard-to-peg Generation Y, and for all the loose ends his appearance implies, he's drawn to precision.

Mahan is a player who knows his driver carries a loft of a digitally measured 9.3 degrees, not the 9 degrees it says on the clubhead, and that the lie angle of his putter is 18 degrees from vertical. Inside the Texas-traditional, 5,800-square-foot home in an upscale Plano neighborhood where he lives alone is plenty of conservative dark-wood décor but also three big-screens symmetrically lined up over the hearth. His paneled office is decorated with all sorts of signed mementos -- gloves from Nicklaus and Woods, shoes from Shaquille O'Neal, memorabilia from the Presidents Cup -- mounted under glass. A huge car buff, the current alpha in his garage is a 2007 Bentley, but Mahan's favorite work in progress is a 1969 Chevy Nova that is being given the full car-show treatment. Mahan has a similar thing for shoes, and the retro FootJoy saddle pattern in glossy patent leather (often in orange, Mahan's tribute to alma mater Oklahoma State) is becoming his trademark with the tour's "in" crowd.

His immersion in details was apparent early. His mother, Cindy, then a buyer at the Nordstrom department store in Orange County's South Coast Plaza, liked to use her company discount to build her only child's wardrobe.

"When he was 10 years old, Hunter had 20 pairs of shoes, all with matching outfits," says his father, Monte. "He'd put on some combination and come down the stairs and say, 'Mom, is this good?' I'm thinking, Oh, man. But the kid turned out all right."

So has his carefully assembled and exceedingly stylish golf game. Mahan is one of the best drivers in golf, long and accurate (fourth in total driving in 2006, third last year). His golf swing and putting stroke are widely admired for their technical excellence, the soundness validated by a penchant for going low. Last summer, Mahan shot three 62s in the span of seven tournaments, a period that included six rounds of 65 or better. His 65 in the final round at the British Open was one of the lowest rounds of the week at Carnoustie (giving him a tie for sixth, his best career finish in a major). He put up the same number in the final round at Hartford, getting his first official victory after a playoff. The surge was enough to earn one of Jack Nicklaus' captain's picks in the Presidents Cup.

Despite his accomplishments, Mahan's parents refer to their son as The Invisible Golfer because, in Monte's words, "you almost never see him on TV or read anything about him." The father knows much of this is because of his son's reserve, at the same time agreeing with Hunter's assessment that "my dad is the kind of guy, when he walks into a room, you notice him." Both men now admit that it was sometimes a difficult presence.

A Santa Barbara beach kid and an avid surfer whose father also loved the waves, Monte was so familiar with the culture that after a stint in the Navy he was hired as a police officer at 28 and became an undercover natural.

"When I went into surfer-bum mode, no one ever, ever guessed I was a police officer," he laughs. "I had the look: long hair, the beat-up car with the board and the baby seat thrown in the back. I knew the lingo. It was just an easy job for me. I never got burned out. Instead of taking overtime pay, I always took the comp time. That and the off-hours made it a good job to free me up for Hunter."

Monte took his son to driving ranges and public courses near their home, eventually joining Alta Vista Country Club in Placentia.

"I'd pick him up from school, and we'd play until dark," Monte says. "I'd take his ball out of the center of the fairway and throw it in the rough, hole after hole, and he knew it was to make him better. I really loved those days."

Monte retired from law enforcement in 1996 after being injured during a fight with a suspect. The family moved to Dallas, where Cindy was a manager at another Nordstrom. Although her salary and Monte's retirement weren't enough to avert the six-figure debt from a full schedule of junior golf, the father and son began traveling the country playing events. Often they were joined by a group that included future pros Sean O'Hair, Ryan Moore and Kevin Na and their parents. Although Mahan went on to win the 1999 U.S. Junior, defeating Camilo Villegas in the final, it was a complicated time emotionally.

"At least you could never use that Harry Chapin 'Cat's in the Cradle' song to describe our relationship," says Monte. "I was around -- maybe a little too much. Sometimes I was way too hard on Hunter. I'd start right in with, 'You should have done this; you should have done that.' But I knew he had tried as hard as he could, and because he'd just gotten beat up on the golf course, he didn't need more of it from me. So I'd stop and just say, 'I'm sorry.' I learned you can't be afraid to apologize to your son. And you know, the kids know when you're wrong.

"That was the difference between Marc O'Hair and myself," Monte says. "Marc and I were friends, but he would never say he was sorry to Sean. If Sean played bad, Marc might lock him out of the hotel room. The kid would have to knock on our door and stay with us."

Hunter and Sean remain tight. "Hunter is a real kind of guy," says O'Hair. "We talk about a lot of stuff, some of it about our dads." Mahan, naturally, has given the subject a lot of thought. "There are very few success stories when parents get really involved with their kids and sports," he says. "When the parents are living through the child, and the child doesn't want to disappoint them -- at all -- that's big pressure. And then sometimes your parents' reactions aren't very good. My dad's reactions when I hit a bad shot were horrible, 'cause he would throw his arms up and stomp around. Then when he wasn't there, I'd have that reaction -- like somebody had to.

"Somehow the child has to figure out that what he does is what he does," Hunter says. "I'm out here to play golf for me, to see what I can do and how can I be the best player for me. The other stuff is his stuff. I know my dad was always coming from a good place, and he was never really wrong in what he said. It was the way he said it. Sometimes he'd say, 'You never listen to me.' And I'd say, 'Who would?'

"When my dad finally decided about a year ago to back away a little bit and let me be more self-sufficient [Mahan's parents are moving back to California], it made all the difference," he says. "My passion, intensity and learning have gone way up. I've always known he loves me, but now our relationship is way better, because in every other way he's been a great father. What happened had to happen. I'm fine with looking in the mirror and saying, 'That was my mistake.' But to look in the mirror and see that it was his mistake -- and I was paying for it -- that would be too much."

At the second stage of U.S. Open 36-hole sectional qualifying last June at Northwood in Dallas, Mahan was so demonstrably negative that his sport-psychologist consultant, Neale Smith, who was his caddie for the event, told him in strong terms that he simply could not continue to play with such an attitude. After a 73, Smith insisted that Mahan show a positive fist pump and say "Yes!" after every shot in the afternoon round. Mahan shot 63, and went on to finish T-13 at Oakmont. "I felt like an idiot," Mahan says, "but it really made Neale's point. I had to stop beating myself up."

"Hunter is getting clearer and clearer on what's good for him," says Smith. "We went with something sort of extreme because he's a visual learner. Exaggerated 'feels' work well."

Mahan works on the feels in his swing with Marius Filmalter, who two years ago replaced Randy Smith, whom Mahan had worked with as his main teacher since age 14. After briefly playing the South African tour, Filmalter became a researcher with a specialty in analyzing putting, but he also applies his ideas of efficient use of the body to the full swing. After Mahan was tested swinging with sensors attached to his body at a Baylor University lab, Filmalter determined he could improve keeping his left arm and left wrist in straighter alignment at the top, and Mahan has been systematic in addressing the issue.

" 'Clear' is a good word for Hunter," says Filmalter. "He likes structure. We have a specific progression to how we want the swing to evolve. The main thing is not to change too many things at once, so he understands it fully before going to the next thing."

Mahan's recent physical transformation has made the swing changes easier. After a semifinal loss to Angel Cabrera at the World Match Play in October, Mahan intensified his fitness regimen and especially changed his diet, employing a nutritionist who plans meals each week. Mahan, at 5-feet-11, has gone from a snug size-34 waist pants to loose 32s.

One of the guides for Mahan's long view is Tiger Woods. The two share commonalities in their backgrounds: the formative competitive years on Southern California's junior circuit, a name that came from one of their father's military buddies, and a gift for deeply immersing themselves in the challenge of getting better.

Mahan is always pleased to be compared to Woods. "I'm a huge fan of Tiger, especially his new swing," he says. "I think his old swing was way too hyped for being better than it was. I watch it on YouTube in slow-mo, and he had to fix a lot of positions, so it wasn't really fluid and efficient. He had to really fire his hips hard because the club was in a tough position, and he really had to hold on to shots. Where he is now is just so much more fluid. He can get away with a lot more now, hit any kind of shot. He was so smart about it, and he's better. And I really look at it, because of the things he does really well, I have to do a lot better."

"The first time I saw Hunter, he was a real quiet, very skinny 9-year-old," says his first teacher, respected Southern California club professional Tom Sargent. "He had a strong grip and a flat swing, and he hit nothing but low hooks. I put his hands in the proper position at the top, a drastic change, and told him to work on that. He came back in a week, and the club was absolutely perfect. I was flabbergasted. And that's basically the swing he's kept. He's just one of those guys with the look in his eye."

"What Hunter can do when he gets it going, you probably can't teach," says his regular caddie, John Wood, a former looper for hot-streaker extraordinaire Mark Calcavecchia. "And he can do it when it counts. The 2005 Q school was our first event, and he was in bad shape after three rounds. But there was no sense of panic, and he went out and shot 66-67-68 to make it easily. When Hunter's in that zone, I don't think he even knows what he's shooting."

This game is not there to give you good feedback. It's mostly frustrating.'

Adds Scott Verplank, a fellow Oklahoma State alum: "We stayed together at last year's U.S. Open, and what I saw was someone who's growing comfortable in his own skin. No telling how good he can get."

In the upward arc of his four years on the PGA Tour, Mahan has put a great deal of thought into making an endlessly complicated game simple.

"That's how I want to play golf -- with simplicity and naturalness," he says. "But we add so much crap to it. What I've had to figure out is that you can't totally control the game. You're going to make a lot more great swings than shots that end up great, more great strokes than holed putts. This game is not there to give you good feedback. It's mostly frustrating. You've got to provide the good feedback to yourself."

Given his history, Mahan is perhaps leery of partnerships, and he calls himself a loner. "Absolutely," he says. "It's cost me some friends, I'm sure. Certainly long relationships with girls. It's a choice. I'm not extremely friendly. It's hard to turn my head on and off. I just find it takes all I've got to play this game. But it's where I want to be."

Asked if it reminds him of anyone else, Mahan laughs.

"Yeah, I guess it's the way Tiger is. And it's part of why he's so great. I don't think we ever thought anyone could be that good. But you think about it, and why not? There's no reason not to be able to do it consistently.

"So I just try to hammer it out every day. I've got a great team, and I want to see a lot more, understand a lot more. Because so much of golf is just a little bit -- this shot here and this shot here, the little things over four days of shots. It's the difference between the really good player who's always up there and the average player who hardly ever is and can't figure out why." And Mahan isn't just talking about his generation when he says he doesn't plan on being one of those.