Tribute

Bruce Fleisher had golf in perspective, making his late-career success that much sweeter

In the summer of 1993, as I was beginning my research for A Good Walk Spoiled, I wanted to put together a group of players who would be the core of the book, pros able to describe life on the PGA Tour from every possible vantage point, ranging from the world’s best players (Nick Price, Greg Norman, Nick Faldo) to rising stars (Davis Love III, Lee Janzen) to youngsters trying to earn their stripes (Paul Goydos, Brian Henninger, Jeff Cook).

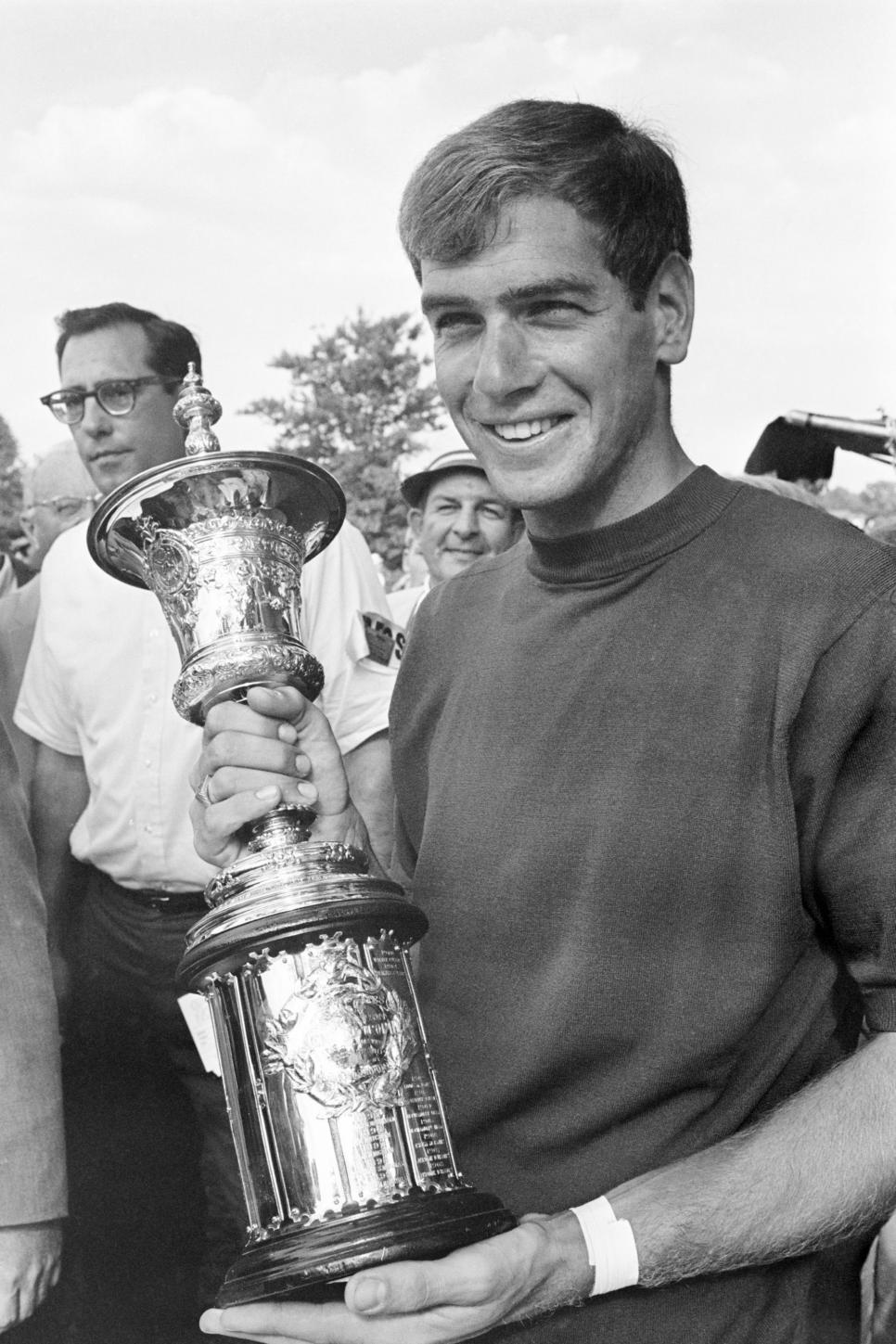

And I also wanted to include Bruce Fleisher, who fit into none of those categories since his story was so unique. Fleisher was 45 and had been on and off the tour for more than 20 years. He was 19 when he won the U.S. Amateur in 1968, wearing the same pair of blue jeans for four straight days at Scioto Country Club in Columbus, Ohio. “I wasn’t superstitious,” he said. “Those were the best pants I had.”

Fleisher had almost lost his wife Wendy from complications during the birth of their daughter Jessica in 1980 (Wendy spent four months in the hospital). He had walked away from the tour in 1984 to become a club pro and had then come back in 1990. A year later, he won for his lone PGA Tour title, the New England Classic in a seven-hole playoff over Ian-Baker Finch after making a 50-foot birdie putt in near darkness for the victory.

Fleisher’s was exactly the kind of story I was looking to tell. I thought about all those things last Thursday when I heard he had passed away after a long battle with prostate cancer at age 72. With all the hype surrounding the Ryder Cup last week, Fleisher’s death was treated almost as an after-thought in golf circles.

I get it. I also think his story is more than worthy of some kind of re-telling, especially since it became an even better one in the years after the book came out.

Fleisher’s grandfather was a Rabbi who was killed by the Nazis during World War II. Fleisher’s father, Herbert, was studying to be a Rabbi, too, when he and his wife had to flee Austria in 1939 to avoid being sent to a concentration camp. They came to the U.S., where Herbert became a successful engineer and they raised four boys.

Fleisher was convinced his father didn’t completely recover from what he saw of the Holocaust before escaping. “I never really saw him happy,” Bruce told me the first time we talked. “I played golf with him a few months ago on a perfect day on a really nice golf course. He made one comment to me after the round: ‘You don’t hit it as long as you used to hit it.’ ”

“I said, ‘Yeah, but I hit it straighter.’ ”

In fact, in 1994, the year I spent a lot of time with Fleisher, he finished 176th in driving distance on the tour, but fifth in driving accuracy.

Fleisher had been a phenom as a youngster. He had flunked out of Furman after a year and transferred to Miami-Dade Junior College. He was there when he won the Amateur—beating a much more elegantly dressed Vinny Giles by one shot (it was during the eight-year period where the Amateur was a 72-hole stroke-play championship). He was low amateur at the 1969 Masters and turned pro when he was 22. He had mixed success on tour before his life changed the day his daughter was born.

At 19, Fleisher was the third-youngest U.S. Amateur champion when he won the title in 1968 at Scioto Country Club in Columbus, Ohio.

Bettmann

“I had just finished playing the last round at the Players when I got word that Wendy had gone into labor,” he said. “I drove down I-95 [to Miami] as fast as I could but got there shortly after Jessica was born. The doctors told me she was healthy and just fine, but there was a problem with Wendy.”

Something had gone wrong during Jessica’s birth. Wendy was so ill that at one point, nurses placed Jessica on top of her so she could feel her child before she died. She survived but was in a semi-coma for months before starting to get better.

“If there’s one thing I know about playing on the tour, it’s that you have to somehow see each week as life-and-death,” Fleisher said to me years later. “After what happened with Wendy, I couldn’t do that. I’d seen life-and-death first-hand, and I understood the difference. I finally decided I just couldn’t do it anymore. I wanted to go home.”

He did—in 1984—for almost six years, living the life of a club pro. But the itch wasn’t gone and, in 1990, with Wendy healthy and Jessica turning 10, Bruce began playing again. He played in Monday qualifiers, got in on occasional sponsor’s exemption and, finally, in 1991, got a call from PGA Tour rules official Jon Brendle on a Wednesday afternoon telling him late withdrawals had opened up a spot for him in the New England Classic if he could get there in time for a Thursday tee time. He got there, shot 64 on Sunday and then beat Baker-Finch, who a week later won the Open Championship at Royal Birkdale.

The first time I sat down and talked to Fleisher at length, we sat on a low stone wall just outside the entrance to the clubhouse at TPC Avenel where he was getting ready to play in the Kemper Open.

“Honestly, all I’m doing right now is counting down until I turn 50,” he said. “Any success I have in the next five years will be gravy. I know my best years are going to come when I get to the Senior Tour because length doesn’t matter out there—accuracy does. And I can putt.”

He struggled with shoulder problems in 1996 and 1997 but stayed at least partially exempt through 1998. Twice, he survived a return to qualifying school. He had to play his way onto the Senior Tour through that tour’s Q school—and then took off the moment he began playing with the 50-and-older set. He won his first two tournaments and seven in all in 1999. He also finished second seven times and made a little more than $2.5 million while sweeping every award there was to sweep.

Fleisher had a feeling he'd do well on the Senior PGA Tour, where he won 18 times after just one win during his career on the PGA Tour.

PGA TOUR Archive

I sat down with him during that euphoric summer and the first thing he said was, “What’d I tell you five years ago?” He had, in fact, called his shot—or shots. The caption I had written to go with his photo in the book had said, “Four years to go to the senior tour … and counting.”

“I dreamed this, but I never dreamed this,” he said that day. “I knew my game was perfectly suited for this tour, that not being able to hit it 300 wouldn’t matter. I used to struggle week-to-week with losing all the time. Let’s face it, in golf, there’s only one winner every week. Everyone else loses. You can make very good money that way, but, at least for me, it was still tough to lose, lose, lose. I still don’t like losing, but at least I’m actually winning some of the time.”

Two years later, he won the U.S. Senior Open at Salem Country Club in Peabody, Mass. In all, he won 18 times on the what’s now called the PGA Tour Champions in his first six years. His last win came in 2016 when he and Larry Nelson defended their title in the Legends division of The Bass Pro Shops Legends Classic at Big Cedar Lodge.

Fleisher’s nickname through the years was Flash, in part because of his name, but just as much because of his quick smile and sense of humor. He liked to tell people that he had “swung right out of my toupee,” when he’d gone for a green from a long way out and he never missed a chance at laughing at himself.

That day in 1999, he told me he’d left his player ID in the car the first day he’d arrived and had go back and get it because the guard on the clubhouse door didn’t believe he was a player. “Maybe if I win this thing, they’ll know who I am next year,” he said laughing.

The tournament was the Lightpath Long Island Classic. He won it that year. He also won it the next year. I’m guessing he had no further problems getting into the clubhouse there.