Pete Bender never minds recounting what happened between him and Greg Norman along the dramatic dunes of Turnberry at the 1986 Open Championship.

Caddies devote entire careers to finding the actions and words that will inspire the best from players under pressure, and perhaps no caddie has found them more often than Bender. Turnberry is where he most notably achieved the caddie trifecta: The right thing at the right time in the right way.

Norman, then 31, was leading by three strokes through six holes of the final round. For three days he had demonstrated some of the most majestic driving ever seen in major-championship golf. But on the par-5 seventh hole, Norman made a quick swing and sniped a low hook into a deep hollow of rough.

The shot seemed portentous because that year Norman had led entering the final round of the Masters and the U.S. Open at Shinnecock but had been unable to hold on. (It would happen again at the PGA Championship at Inverness, where Norman completed the ill-fated Saturday Slam.) Bender, who had been on Norman's bag for two seasons, knew the criticism and scrutiny from those failures were making it that much harder for Norman to win his first major.

"Greg had started walking faster and talking faster, and that drive was a warning light," says Bender, now 60. "It was like I felt this click, and I knew I had to do something. I got up beside him as we left the tee and said, 'Greg, do me a favor: Let's slow down a little and enjoy it.' "

Greg stopped and looked at me, and I said, "Easy. Just walk at my pace. I'm here to help."'

But Norman barely nodded and resumed his hurried stride. That's when Bender decided that Norman needed a firm hand, caddie deference be damned. "I caught up to him and pulled on the back of his sweater," Bender says. "Greg stopped and looked at me, and I said, 'Easy. Just walk at my pace. I'm here to help.' "

Norman saved par and re-established control with a 4-iron to five feet at the eighth. Still, when Norman got to the 17th green with a five-foot birdie putt that would have given him a six-stroke lead, Bender remembers him saying, "Pete, I'm too nervous to see the line. Tell me where to hit it, and how hard." Norman knocked the putt four feet past the hole but managed par. On the final tee, Norman reached for the driver, but Bender kept his hand on the headcover, handing Norman a 1-iron. He got no argument, and Norman won his first major.

Did Bender's cashmere clutch matter? The clutchee says it did. "Pete read me right," says Norman, who will be returning to Turnberry a year after his tie for third place (and 54-hole lead) at Royal Birkdale. "That's what a good caddie does: He identifies what the player needs psychologically. He sees a situation that sometimes the player doesn't see, and he has the courage to say so."

It has been that way for 40 years—the time Bender and close friend Andy Martinez have had regular bags on the PGA Tour, making them the deans of tour caddies. They've caddied for Hall of Famers, and they've shouldered bags when there was no money in it. To Martinez, what happened at Turnberry in 1986 is simply an example of what Bender does.

"Pete is extremely intuitive with really high emotional intelligence," says Martinez. "On the fly and in the moment, on the golf course and off, he makes the right decision. I've seen him do it consistently for 40 years."

In that time, Bender has had regular stints on the bags of Hall of Famers Jack Nicklaus, Raymond Floyd and Lanny Wadkins as well as Norman. Bender has 28 official career wins, and though that number is surpassed by Steve Williams (Tiger Woods) and Jim Mackay (Phil Mickelson), what's more significant to Bender's peers is that he has won with seven players: Jerry Heard, Wadkins, Norman, Floyd, Ian Baker-Finch (the 1991 Open Championship), Rocco Mediate and Aaron Baddeley, for whom he has looped since 2004. It's a number believed to be unmatched in the history of the PGA Tour.

"Pete always fills the void," says veteran caddie John Sullivan. "He knew Greg needed that tug at Turnberry, but maybe another player he would have left alone. The point is, he can adapt and improve anybody. That's why he's won with so many different players. That's what makes him the best ever."

Bender might not possess the kind of evocative nickname that is part of caddie romance—handles like Reptile, The Piddler, Psychological Bob, Reefer Ray—but his Pistol Pete is descriptive and on point.

"I always want to read the putt, pull the club, discuss the shot, whatever, especially in the heat on Sunday," says Bender, his voice still raspy from chemotherapy and radiation treatments he endured last year to combat tonsil cancer. "That's what I'm there for. Under pressure, it should be easier for a caddie to make a good decision than for the player. The caddie isn't the one on the spot. We should be able to see things as they are and present them as normal as possible. The only thing that messes that up is when a caddie is afraid of saying something he thinks could get him fired. That's when a caddie chokes -- when he becomes a 'yes' caddie. You've got to be willing to be fired for what you believe."

Adds longtime tour caddie Steve Kay: "You get paid for your reputation for being right, and nobody's reputation is better than Pete's."

Bender is proudly old school—he has never worn shorts to caddie, never used a range finder to get yardages, never employed a digital green reader—and he has always stayed with the single strap. "I trust my eyes and my feet," he says. He also bemoans changes in technology that have made today's players less inclined to attempt different shots. "These guys just want to bang everything hard, high and straight," he says. "The guys in the '70s and '80s had a lot more shots. I'll admit it's taken some of the fun out of caddieing." At the same time, Bender is well known for encouraging younger caddies, and for his enthusiasm.

"Pete and Bruce Edwards loved what they do as much as anyone I've ever met," says caddie Bob Low. "Players feed off those positive vibes, which is why Pete has always had good bags. He has quiet charisma."

The comparison to Edwards, the beloved caddie for Tom Watson, is both affectionate and ominous. Edwards died from ALS at 49 in 2004, and in February 2008, Bender was diagnosed with Stage III tonsil cancer. Treatments left his throat so raw that he couldn't swallow, and he lost 50 pounds, to 128. After a 62-day hospital stay, Bender went into seclusion. Most feared they would never see him again. Instead, Bender emerged to caddie for Baddeley earlier this year, buoyed by body scans that tell him he is cancer-free.

Pete Bender caddieing for John Cook at the 1994 PGA Championship

PGA TOUR Archive

"You don't last as a caddie if you don't love it, but after getting sick, I think I love it even more," Bender says. "I appreciate everything more, and especially the two British Opens."

At Turnberry, Bender was the top caddie in the game. Norman was the biggest attraction, and by making more than $1 million in prize money worldwide he enabled Bender to become the first caddie to earn more than $100,000 in a year. With a self-assured attitude and chiseled looks that matched nicely with Norman's, Bender got a derisive nickname: The Million Dollar Caddie. Part of it was that although Bender was friendly, he didn't hang out with his peers.

"When you have the No. 1 player and you're the No. 1 caddie, you're going to have a lot of jealous people," says Bender. "It's better in that situation to be a maverick, just staying in a small group. I understand why Steve Williams is like that."

Like Williams, Bender was riding the game's show horse. At a time when the majority of players were still using persimmon drivers, Norman was probably the longest and straightest driver relative to his competition in the modern era. "It gave me a tremendous advantage, an advantage that I would eventually lose when metal drivers allowed everyone to be much straighter," says Norman. "But at Turnberry the fairways were very narrow, and the rough was very deep. Most guys were laying up with irons, but I knew I could hit driver.

"I could see that the course was set up perfectly for me. I said, 'Don't change a thing. Just execute that same mind-set.' I got lost in that, so that it was like Augusta and Shinnecock hadn't even happened. Pete reinforced that."

Adds Bender: "The harder Greg swung, the straighter he hit it. It gave him an unbelievable weapon, especially in the majors with rough. When I first started with Greg, I think he thought Seve was better than he was. I kept telling him, 'Greg, the way you drive it, you're better than Seve. You're the best.' "

But Bender knew that was only if Norman could control his emotions. At the '86 Masters, after making four consecutive birdies to tie for the lead, Norman had decided on his own to try to get a high, cut 4-iron to a back-right flagstick at the 72nd hole instead of hitting a more basic shot to the middle of the green and taking his chances in a playoff with Jack Nicklaus. "We agreed on the 4-iron, but Greg went against the game plan," says Bender. "If I had known he was going to try to hit the high cut, I would have tried to talk him off it. Afterward [after missing the green and making bogey], Greg told me, 'I wanted to birdie the last five holes and beat Jack.' "

At Shinnecock, Norman played a practice round with Nicklaus, who told Bender, "If he doesn't win, something's wrong. I've never seen anyone hit the ball that well." But Norman lost his rhythm in the third round after confronting a spectator who had called him a choker.

Excitement got the best of Norman again during the second round at Turnberry, even as he was shooting 63 on a day that the field average was 11 strokes higher. On the 18th hole, Norman had a 28-foot birdie putt for a 61, but he ran it four feet by and missed coming back. "Greg said, 'I wanted that 61,' " says Bender. "I mean, what was wrong with 62? That would have been the record." Bender was part of another record when Baker-Finch shot 29 on the front nine of his final round at Royal Birkdale in 1991. But it was on the back nine that the champion would appreciate his caddie even more.

Greg said, "I wanted that 61." I mean, what was wrong with 62? That would have been the record.'

"Pete is the best I know at instilling confidence, and because I was never a tremendously confident player, I needed that," says Baker-Finch. "I remember the 4-iron I had to the 16th hole when I had a two-stroke lead. Pete talked me through the yardage and the club in such a way that I addressed the ball with this great calm. I hit it right at the flag, and as it was in the air I said, 'You like that one, Petey?' I'm sure that sounded boastful, and it was very unlike me, but it was a product of how Pete had helped me feel. And his answer was, 'Love it,' in a very decisive tone."

John Sullivan calls the ability to induce such flow one of Bender's gifts. "Pete has a way of conveying an opinion that leaves no room for doubt," Sullivan says. "Pete will say, 'It's a perfect 7-iron. You're going to knock it stiff.' Or 'It's a ball outside the left. Just hit it there, and I'll pick it out of the hole.' He's contagiously positive."

Bender has been that way since he began caddieing, at 15, at La Rinconada Country Club in Los Gatos, Calif. Though he had been playing golf for only a couple of years, Bender's attentiveness, enthusiasm and knack for reading greens prompted a promotion to caddiemaster. "I liked to play," says Bender, still a single-digit player who could sometimes beat Nicklaus in putting matches, "but I found I liked helping someone else enjoy their round as much or more. To this day, if someone in a pro-am thanks me and says, 'That's the most fun I've ever had playing golf,' that's as good as it gets."

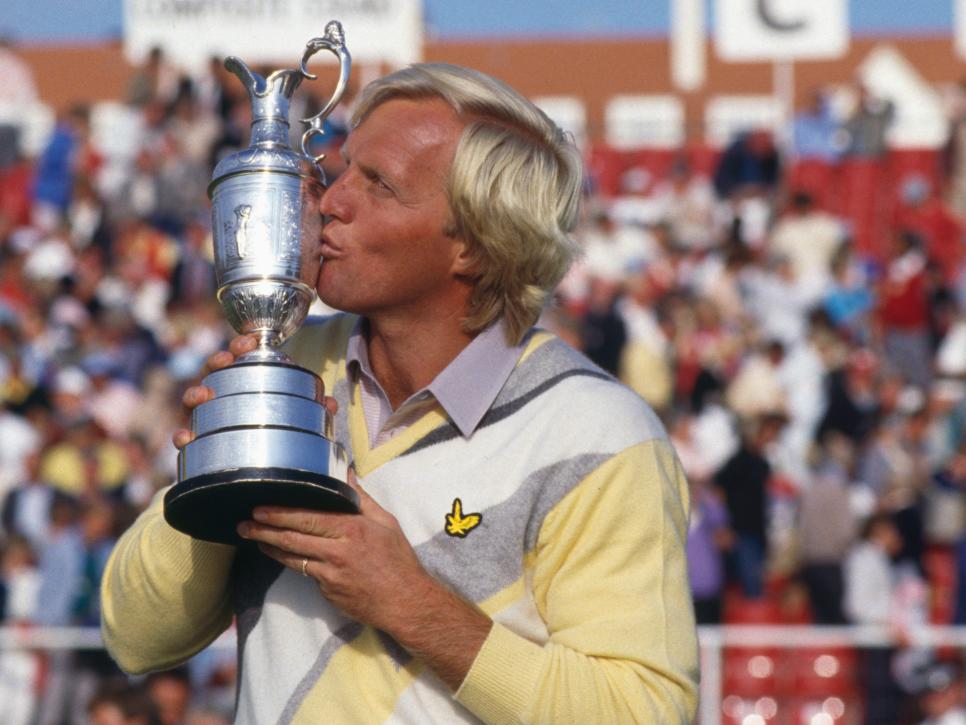

Greg Norman kisses the claret jug after winning his first major title at the 1986 Open Championship at Turnberry.

David Cannon

Bender's introduction to serious competition came from looping for a group of prominent local businessmen who bet heavily. "It wasn't rare for a few thousand to be exchanged," he says. "They'd play a best-ball match, but usually I'd read putts for all four of them. The winners would give me a cut. I could make $100, $150 a day, which went a long way in our house. But what I found out is that I loved being in that position. I love the pressure. Give me the pressure."

The traits came from a difficult background. Bender grew up with a brother and four sisters in San Francisco, the son of a car salesman and former police officer who left the family when Pete was 14. "He was physically abusive—to me, to everybody," says Bender. "He drank. Once he broke my nose for coughing too loud. My mom kept taking him back, but my older brother and I finally said, 'Enough is enough,' and we ran him off. I never saw him again. I heard he died about five years ago. I didn't feel any remorse. To be honest, I hated my father."

Bender was married for 18 years before divorcing in 1996. He fathered no children but says he speaks regularly to his two grown stepdaughters.

"I have to admit," he says, "when I see a good father-son relationship, it makes me kind of jealous."

Most of the money he made as a teenage caddie went to his mother, Ann, who was often working two jobs. Now 87 and confined to a wheelchair, Ann lives in Bender's home in Roseville, Calif., with his twin sister, Carol, who is severely diabetic and has always lived with their mother. Bender, who even in the wild '60s and '70s rarely drank alcohol and never smoked, cares for his mother and sister during weeks when he's home and arranges for their care through other relatives and close friends when he isn't.

"I call them every night—never miss," he says. "My mother has been everything to me. She never complains about anything. Never. She's my role model." He pauses. "It's a good thing I like pressure," he says. "I've had it all my life."

No wonder that despite the ragtag existence most caddies lived on tour years ago, Bender saw the life as a liberating adventure. Although he admits working for Jim King in the late '60s at the Lucky International in San Francisco was no fun. King was an ex-boxer and fringe player known for physically intimidating other players and officials, and he was a nightmare for caddies. "While we walked the holes, he had this way of punching my left arm with his right hand when he wanted to make a point, but it was no love tap," Bender says. "By Saturday, my arm is black and blue, and I can hardly lift it. That was a one-time deal."

It's a good thing I like pressure. I've had it all my life.'

Bender met Martinez, an all-sports jock, at a tour stop in Phoenix. "I saw this guy with a headband and long hair running out on the course," says Bender. "He was fast, and he was jumping over bushes. I'm going, Who is this guy? It was Andy getting pins [locations], which not everybody did in those days. We started talking, and right away we're traveling together. We've been close since the first day. It's funny because we're pretty different, but we've always been there for each other through different players, through divorces, through everything. Basically, I consider Andy my brother."

Martinez, a thoughtful, analytical sort, became a born-again Christian in 1988 after two years in which his first marriage failed and he lost both parents and a brother. "You know, human beings will disappoint each other," he says. "We fall short. But Pete has disappointed me less than anyone I've ever known." In the early days, money was scarce, with the going rate on tour $25 a round and 3 percent of winnings. But bags were plentiful, and many caddies who hung out in the players' parking lot garnered a job with "Jess," as in "jess anyone." There was a communal spirit. Caddies would pile into cheap hotels, often six to a room, with so many sleeping on the floor that "Jonestowning" became part of the politically incorrect caddie argot. When the West Coast swing would end in Los Angeles, several caddies would get in a car or van on Sunday evening and drive in shifts to Miami, stopping only for gas and arriving Tuesday morning. "And then we'd work the practice round at Doral that afternoon," says Bender. "We were all doing it for passion of the game and the life. I mean, if you made $10,000, that was a huge year."

When Bender first joined the tour, the vast majority of regular caddies were African-American. And though golf had not been particularly kind to them, the black caddies were kind to Bender and Martinez. "I'll never forget how they treated us," says Bender. "We were coming into their world, and they welcomed us. They showed us the ropes. They looked out for us."

"Pete and Andy and Bruce [Edwards], it was like we raised them," says Alfred (Rabbit) Dyer, Gary Player's longtime caddie, who is retired in Houston. "Nice young kids. We did it because they were gentlemen. Sure, they weren't black, but they were the new blood. It was part of the times. All that was going on socially and racially at that time, a young black kid wasn't going to carry a bag."

Bender caddied for Tom Shaw, and Martinez landed an emerging Johnny Miller. When Miller was winning big, it was Martinez who became the game's most dynamic and photogenic caddie, especially for the way he would crouch directly behind Miller to line him up.

"I could see things in Pete that maybe he couldn't see," Martinez says. "I knew he had an extraordinary ability to focus."

The best example occurred in a laundromat in Akron, Ohio. Bender, who grew up flipping baseball cards, later developed the ability to throw playing cards for distance and to hit targets. "I can still knock a bowling pin over with a playing card," he says. At the laundromat, Bender was idly flipping cards into a basket while he and Martinez waited for their clothes to dry. "This huge guy, probably 400 pounds, is the only other guy in there," Martinez says, "and he tells Pete, 'Hey, you're pretty good.' Pete says thanks, and the guy says, 'Let's see you throw that card so it sticks between the two entrance doors.' "

Bender picks up the story. "There's no way. It's 50 feet away, a half-inch space. But I go, What the hell, really concentrate, and fling it as hard as I can. And I swear, it sticks right between the doors. It was like one of those special-effects movies. The fat guy went berserk; I seriously thought he was going to have a heart attack. I tried not to act surprised." Says Martinez: "To this day, the greatest shot I have ever seen."

In time, Bender began working for more prominent players. He was on the bag for his first victory, with Heard, in 1972, and after that spent six years with Wadkins, who "taught me how to be an aggressive caddie, because you could not hide a pin from the guy." Says Wadkins: "What I liked about Pete was that he understood all the different shots I could hit. He would get my imagination going, and it made me better."

Bender moved to Nicklaus in the early '80s. "Jack was tremendous," says Bender. "He paid well and always treated me with respect. It was a thrill to see his game close up. But honestly, his judgment was so good I didn't feel like I had much to do."

'We were all doing it for passion ... I mean, if you made $10,000, that was a huge year.'—Bender on caddieing

It was during practice rounds with Nicklaus that Bender would come to work for Norman, a partnership that ended in 1987 with a phone call the day before Thanksgiving. "Greg called and said he had to let me go. I asked why, and he said, 'We've become too close.' It's always the player's prerogative. I think he just wanted to make a change. We'd had a lot of tough losses, the last one with the Mize chip-in [in the 1987 Masters playoff], especially."

Asked for his version, Norman says, "I really can't put my finger on it."

Bender gained another nickname while caddieing for Nicklaus at the 1984 PGA at Shoal Creek. During a practice round with Lee Trevino and his caddie, Herman Mitchell, Nicklaus asked Bender if $2,000 for the week was a fair amount.

"I think for a player of your caliber," Bender replied, "$2,500 is more appropriate."

"Jack thought for a second and agreed," says Bender. "Well, Herman couldn't believe it. He goes, 'You are my hero. You held up the greatest player in history.' From that day on, Herman always called me Iron Balls."

Bender would live up to the name often, especially in the last round of the 1993 Masters while caddieing for Chip Beck, who trailed playing partner and eventual winner Bernhard Langer by three strokes after a good drive on the par-5 15th. Bender, with a microphone picking up the dialogue, urged Beck to go for the green, but with 236 yards to clear the water, Beck declined, laying up and making par. Bender was livid. "I told him after the round, 'Chip, you hired me for just those kinds of situations, and then you don't listen to me.' We lasted only a few more weeks."

Since then, Bender has worked regularly for only two players: Mediate, with whom he won three times, and Baddeley beginning in 2004, leading to two victories. "Probably the two nicest guys I've ever caddied for," says Bender. "At my stage, that means a lot. Being treated with respect, that's a big thing."

During his time with Mediate, Bender began saving for retirement. A former surfer who loves water, Bender began fly-fishing seriously about 10 years ago. During an event in Ireland in 2004, Bender went out with a bunch of players and "frankly, I put on an exhibition." Last year he was figuring that Baddeley would be his last bag before he would buy a place where he could spend his days casting a swift-running stream.

But during the 2008 WGC-Match Play in Tucson, Bender began to feel so weary he could barely make 18 holes. When Baddeley battled Tiger Woods into extra holes before losing on the 20th, Bender says, "I couldn't have gone another match." He went home and was diagnosed with cancer in his tonsils and lymph nodes.

Bender was admitted to the hospital, where he declined the use of a feeding tube, telling doctors, "I'll rough it." Unable to swallow, he took all his sustenance intravenously and dropped weight at an alarming rate. "I wasn't sure I was going to make it, and I was getting so depressed in the hospital," he says. The turning point came when his mother and sister came to see him, and his sister collapsed from a heart attack. "That was it; I knew I had to get out of there to take care of them," says Bender. "I called Andy, and he came and got me. It was against doctors' advice, but they gave me this backpack that gave me all my medicines and food. I had to wear it when I slept and even when I took a shower."

Bender went into solitude. His voice mail left the poetic message, "I'm out fishing … for rainbows."

"Pete just went within himself," says fishing buddy Dave Brown. "He focused all that energy on getting well and coming back."

In the first months of his return to the tour, Bender has regained 30 pounds. And he has a dream: He wants to develop a television show in which tour pros fly-fish, modeled on "The American Sportsman," his favorite show as a kid. "I've got a lot of players who will do it," he says. His goal is to help Greg Rita, a longtime caddie who has a malignant brain tumor. "The tour hasn't stepped up enough to help the caddies who have gotten sick," says Bender, whose medical care ran more than $500,000 but was mostly covered by his insurance. "It's really only been some of the players who have helped the caddies."

Bender brings the same focus to his fly-fishing trips that he has used in 40 years as a regular caddie on the PGA Tour.

"I miss it a lot, just like Pete did," says Rita, 53, who stopped caddieing after a seizure in 2007. "I'm happy Pete was able to get back. All of us, the players and the caddies, have always had so much respect for him. He's just a good man."

One always trying to do the right thing at the right time in the right way.