News

Arnie's World

The impromptu receiving line starts forming at the back of a cart near the 10th tee, where the pros begin their tournament round at Bermuda Dunes (Calif.) Country Club. It isn't set up to be a receiving line exactly, but that's the way it turns out, because Arnold Palmer is sitting in the cart, legs crossed, and he's watching.

Every pro follows the same path after he hits his tee shot . . . a short detour to the right, a quick hello to Palmer, a handshake, perhaps a couple of words of encouragement, then a left turn before heading down the fairway. Mark Calcavecchia, Rich Beem, Brad Faxon, Corey Pavin, Charley Hoffman, Justin Leonard, Tommy Armour, Jason Gore, D. J. Trahan. One by one, they stop, visit, smile, chat and move on. After awhile, the scene evolves, the pace slows, the emotions surface, the view changes, almost as if it's become something else altogether, like an audience with a world dignitary or political leader.

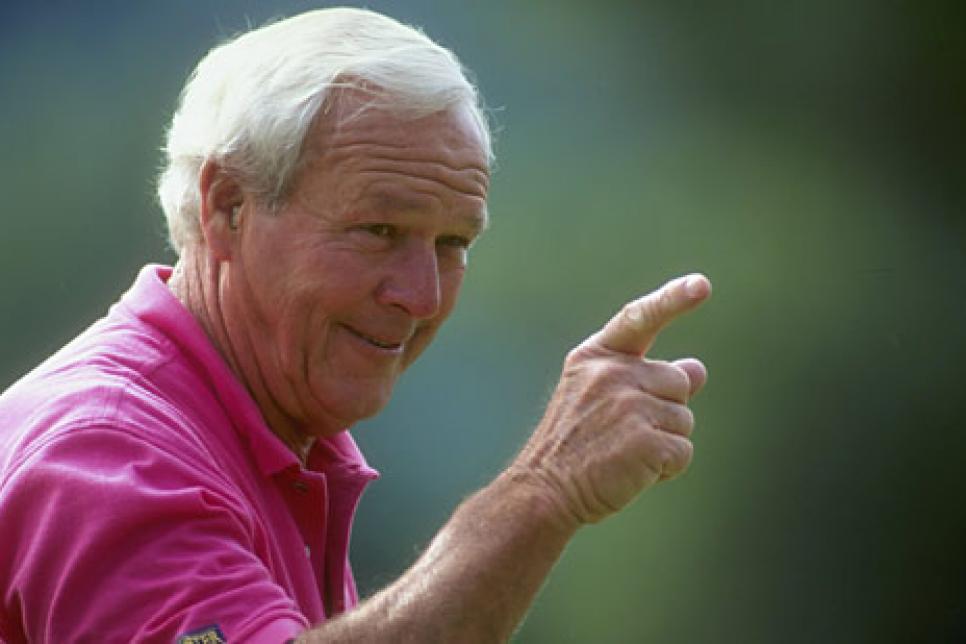

. . . . In fact, that's exactly what it was. Palmer is such a package, and more, even at 79 -- especially at 79. He hasn't played a regular Champions Tour event in three years or a PGA Tour event in more than five, but judging by the number of players who want to say hello or the fans who ask him for his autograph, Palmer stands tall among golf's elite.

He's a people magnet. It's as if asking him to sign a program, a ticket stub, a cap, a shirt or a scrap of paper, or even being near him, whatever power or magnetism or charm that fills him is maybe going to rub off.

And who's to say they're wrong?

If there was a position as Ambassador to Golf, Palmer would fill it, but it's a job he's already held unofficially for years -- not that he's complaining.

"I do get tired, but it's not a burden," he told GolfDigest.com. "It's more of a pleasure than anything else. I think the fact that people have been so nice to me says a lot."

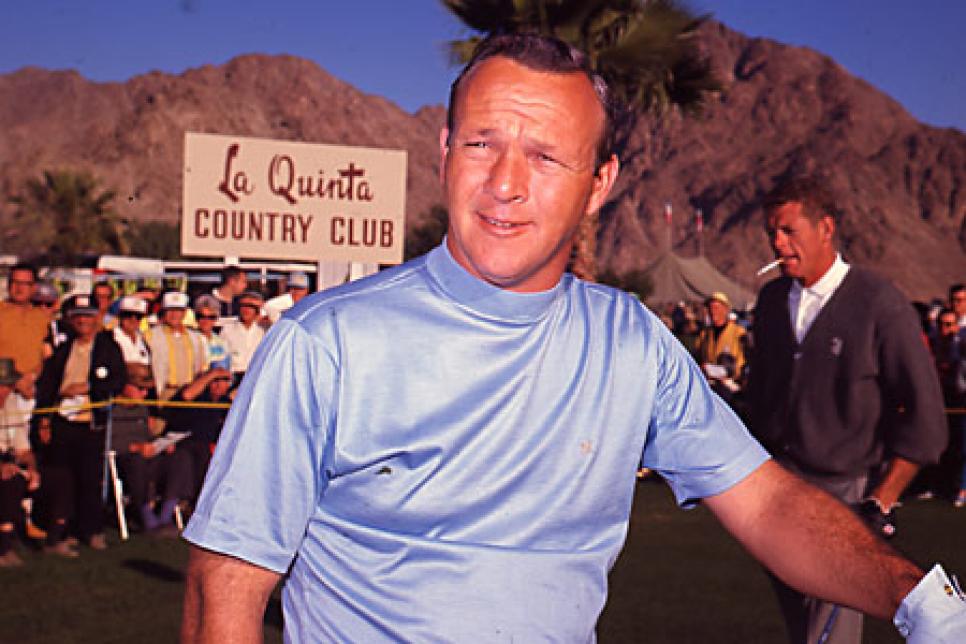

Palmer looks sharp, especially on this day, decked in razor-sharp gray slacks and a blue sweater. Once, when there was a break between groups, Palmer turned his head, looked down the fairway and said softly, to no one in particular:

"I know every blade of grass."

There are many courses where he could say the same thing, especially this week at Bay Hill Club and Lodge, where the Arnold Palmer Invitational is being played. It's a tournament that's been played at Palmer's Bay Hill since 1979, and a mainstay on the PGA Tour as one of the highlights of the Florida swing

For a man who turns 80 in September, Palmer's clout remains unshakable, his reputation more formidable than ever. That's what it means when you have four Masters titles, seven major championships in all, 62 victories on the PGA Tour, four Vardon Trophies, four earnings titles, a Hall of Fame membership, a Presidential Medal of Honor, the Patriot Award from the Congressional Medal of Honor Society and a charity fund-raiser for the Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children and Women in Orlando.

Palmer is still near the top of his game. Last year, he made an estimated $30 million to rank No. 4 in the Golf Digest 50, a list of the top earners on and off the course. Tiger Woods is No. 1, with a total of about $117 million, but Palmer's estimated earnings in 2008 were still more than Greg Norman, Ernie Els, Sergio Garcia and, yes, even Jack Nicklaus.

And yet, however important money may be, it's not the real Palmer story. According to Gary Player, the Palmer story is the people's story.

"Arnold has always had sort of a partnership with his fans and signing autographs and such," Player said recently. "I've seen dozens of players, how they treat people is frightening. Arnold has always behaved impeccably.

"He is the most charismatic golfer I've ever seen. He was lucky. He fell out of bed with it."

He also worked for it.

By now, the details of Palmer's rise to the top of his chosen field are well known, but seen put together, even through the distance of years, they're a fascinating piece of Americana from a time long since past. The eldest of four children, Palmer was born in Youngstown, Pa., and raised in Latrobe, in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains, east of Pittsburgh. He was the son of Doris and Milfred Jerome Palmer. Arnold's father, known as Deacon, quit school at 15 and went to work for a steel company in Latrobe. Since the steel company owned stock in the new Latrobe Country Club, Deacon signed on as the course superintendent and later served as the pro.

Arnold was 4 when Deacon cut down a club and gave it to him.

And more than three quarters of a century later, Palmer remembers those days clearly.

"When I was a little guy, I used to go to work with him on the golf course. He cut me down a little golf club and I was set. I had two toy guns on each side and a golf club and I spent my time with him. I suppose I was 3 years old. And then I just grew up. I was a cowboy, I played cowboys and Indians in the early days, then I got onto the game and I started playing.

"I just played by myself and I played with my sister, Lois Jean, who was two years younger than I was. It was a natural thing. I played baseball, football with the guys, and part of that was because there weren't a lot of young kids playing golf. But then I started playing with the caddies in the caddie yard and I was caddieing. And that became major to me."

Not long after Deacon was giving lessons for the going rate of 10 cents for half an hour, Arnold began mowing greens and fairways and shagging balls for 25 cents an hour.

The son broke 55 for nine holes at age 7, broke 40 when he was 12 and shot 71 in his first high school match – remarkably also at age 12.

"I started playing with the high school golfers even before I was in high school. And, of course, my objective was to beat everybody I played with."

The record shows that's almost exactly what happened.

What would become one of the most celebrated careers in golf likely got its traction in 1954, when Palmer won the U.S. Amateur at the Country Club of Detroit. He joined the PGA Tour in 1955 and won the Canadian Open. In 1956, he won twice more and the next year, he won four times.

Then, in 1958, Palmer won the Masters.

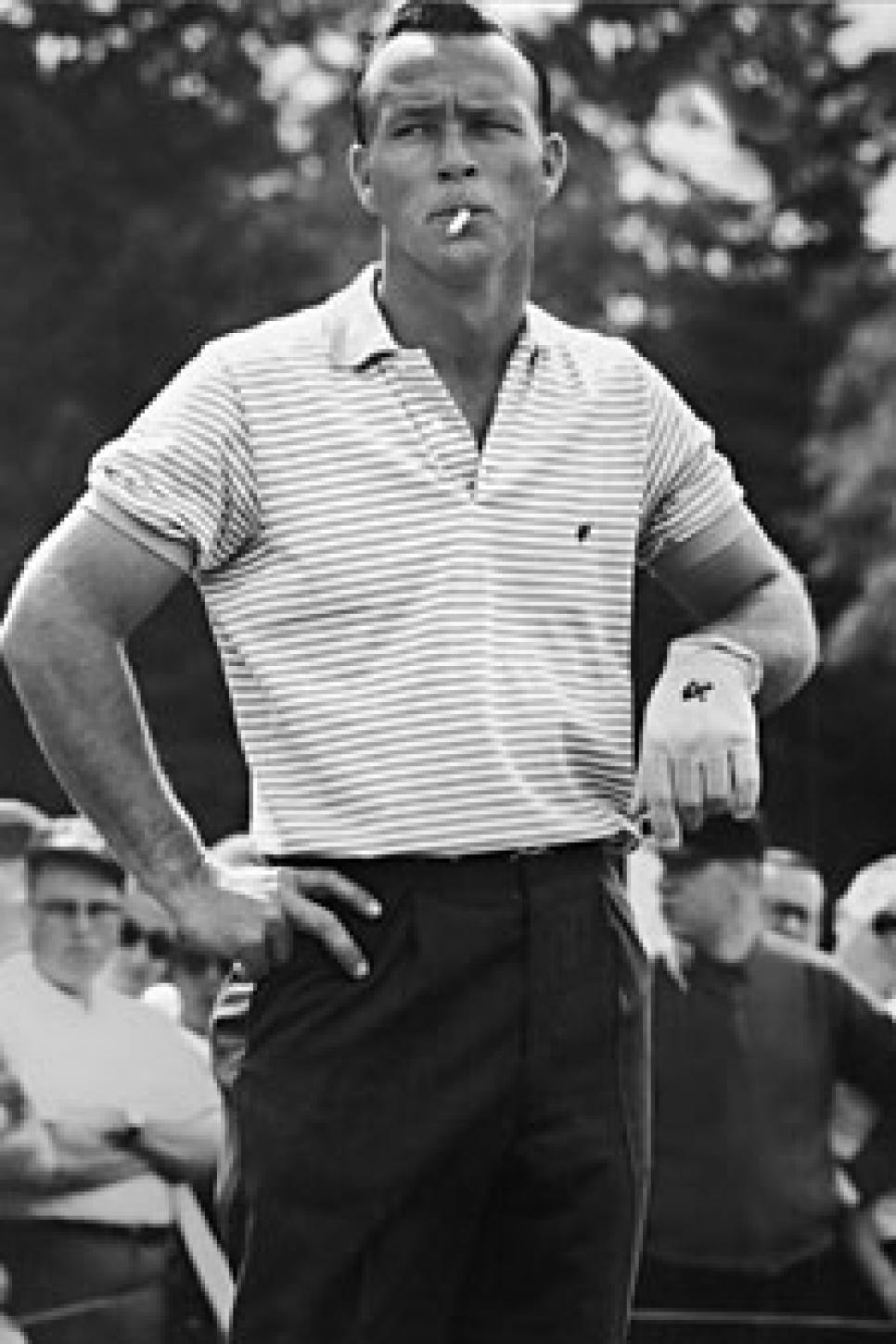

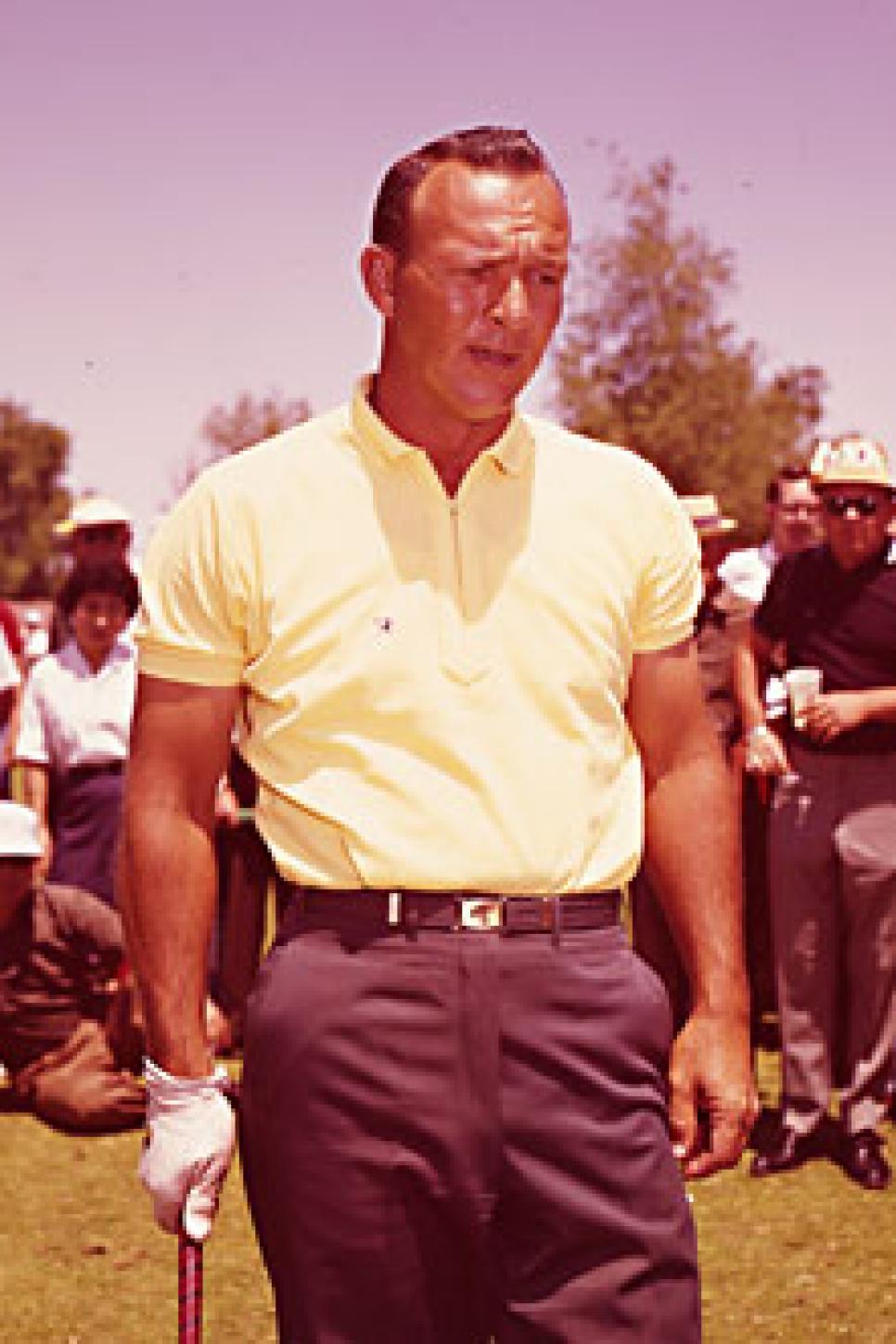

The lavish expanse of fairways, majestic rows of trees and the dangerous, rolling greens of Augusta matched up well with Palmer's trim waist, powerful forearms and the dangling cigarette from his lips. As it turns out, it was an enduring association, and also perfect timing -- the advent of golf's entry to a new level of popularity thanks to Palmer's charisma combined with the clout of television.

Palmer became "the King."

"We'd all like to be Arnold Palmer, he set the tone for a whole generation of players, and we owe him a huge debt of gratitude," Fred Couples said.

Palmer played the Masters 50 times, the last occasion on a Saturday in 2004. The scene of him walking the uphill 18th fairway of Augusta National Golf Club for the final time was a poignant one. His red shirt and white hair stood out in bright contrast to the prevailing green backdrop. As his ardent followers in "Arnie's Army" cheered every step, Palmer choked back tears, removed his visor and waved.

During half a century at the Masters, Palmer took 11,248 shots in 150 rounds and played 2,718 holes, covering roughly 600 miles. Of the 93 players who started the 2004 Masters, 81 had not been born when Palmer played his first Masters in 1955.

Even though his Masters days were at an end, Palmer's reach had long before extended beyond the golf course and into the boardroom. Very early in the Palmer Era, entrepreneur Mark McCormack came on to organize Palmer's finances, and out of that arrangement grew the powerhouse International Management Group. It can be traced as the start of what has become the agent system, and along the way, Palmer's list of sponsors through the years has included everything from motor oil to tractors.

Player said that McCormack's first client list, of himself, Palmer and Nicklaus wasn't so shabby.

"Genius," Player said. "Can you imagine signing up your first three clients like that? And signing them up when they all came to the front?"

According to PGA Tour commissioner Tim Finchem, the first may have been the most important. He said there has never been anyone to equal Palmer, and for a good reason.

"I always say that when golf and CBS and Augusta and Arnold Palmer came together in 1958 . . . that was the beginning of [the] modern golf era . . . the most charismatic figure in the history of the game."

That Palmer cut a dashing figure is an understatement. His good looks inspired a growing following of fans, and his uber-athletic, swashbuckling style of play cemented his relationship with them. Palmer took chances. Some of them worked out great, some produced tragedy. It was golf theater at its best.

Said Tom Watson: "Arnold Palmer and television were made for each other."

Meanwhile, Palmer's early-on relationship with Nicklaus, his on-course rival, was the talk of golf, with Palmer serving as the reigning champion and Nicklaus his rising challenger. Many fans were far from neutral, but Palmer said his connection with Nicklaus has never been anything other than close.

"We were good friends. You must remember that I was almost 11 years older than Jack. And when he came along to play the tour, I was the guy that was talking to him . . . well, he came to me first and we talked and I helped him, kind of get him acquainted to what was happening on the tour and what he was going to have to do. He signed up with Mark McCormick and it was through me that that happened.

"We were always good friends, from anytime that I can remember. That didn't mean we weren't out to beat other, because we were. We tried like hell to beat each other from the day we started. It never changed."

Nicklaus maintains any personal rivalry with Palmer was contrived by the media.

"Arnold and I have been friends," Nicklaus said in an interview with GolfDigest.com recently. "Sure, we've had our differences. Absolutely. I mean, two guys don't walk around in euphoria all day long. I mean, we were obviously competing, and when you compete, you have issues. But if I ever needed anything, I know Arnold would be there for me."

It was in the 1960 U.S. Open at Cherry Hills Country Club outside Denver, where Nicklaus captured everyone's attention as an amateur, that Palmer impressed even more. He had already become well known for his making a charge out on the golf course, and maybe the most famous of them was at Cherry Hills. Palmer started the final round seven shots behind Mike Souchak and five shots behind Ben Hogan, but drove the green at No. 1 and birdied six of the first seven holes. He won. Nicklaus was second, by two shots.

It turned out to be Palmer's only U.S. Open triumph, although he was second or third four other times. Palmer was either second or third in 11 majors.

These days, Palmer no longer plays much golf, because he isn't happy with the standard of his game, although he enjoys the company of a small circle of friends on the golf course in friendly matches.

Just don't say he's mellowing. Mike Weir is pretty clear that isn't happening after he skipped playing Bay Hill a couple of years and then ran into Palmer.

"He gave me a little stare-down, like 'You'd better start showing up,' '' Weir said. "The fire was still there. I got a kick out of that."

Palmer said he is indeed no pushover. "I don't know that I'll ever be mellow. When I do things, I still compete. And I hope that I compete until I can't get out of this chair."

So Palmer is getting closer to beginning his ninth decade. Growing older is part of the game, another part of life, he says, just as death is part of the game as well. He knows he's getting older.

"I'm afraid I do."

Palmer's personal losses bother him deeply. He's not afraid of dying, he said, and death has accompanied him for so long already that adapting to loss is something to which he has grown accustomed.

"It's not easy. You go back to my father, my mother. And of course, Winnie. We raised a family; we were married for 45 years. You just can't walk away and forget things like that. A lot of my friends. (Longtime design partner) Ed Seay is gone.

Palmer said his first encounter with a painful loss was when his Wake Forest roommate, Bud Worsham, was killed in an automobile accident. Worsham was the brother of 1947 U.S. Open champion Lou Worsham and the one who had helped convince Palmer to come to the university.

Palmer said it was Homecoming at Wake Forest when Worsham, along with Gene Scheer, died when their car ran off a road and overturned.

"I was supposed to be with him, but I got tired and went to bed. Things like that, you don't ever forget. I'll always remember. He was a brother."

And Palmer's voice broke.

He is as famous for carrying his emotions on his sleeve as he was for rolling up those same sleeves to show off his biceps.

Player said it is entirely in Palmer's character for his friend to reveal his emotional side.

"Don't be too proud to laugh in life; don't be too proud to cry in life," Player said.

If things go right, Palmer will have a lot more to laugh about, more Bay Hill tournaments to watch over, more grandchildren to add to his seven, more travel plans with his wife, Kit, who he married in 2005, and more time to remember how many lives he's touched simply by being himself.

But on this morning, on the back of the golf cart, Palmer isn't thinking about that. He's remembering the words his father said to him long ago about what's really important.

"I will never forget, they are embedded in my mind and have been for all my life. He stressed without any question, just treat people like you'd like to be treated.

"I suppose I'd like to be remembered as someone that made his contributions to the game and to people and helped them maybe understand what it's like to be a good guy."

At that moment, someone shoved a program in front of Palmer. He signed it. He smiled.

"Hello, what's your name?"

The King and his court are still in session.