News

Why Johnny Miller's Oakmont 63 still matters

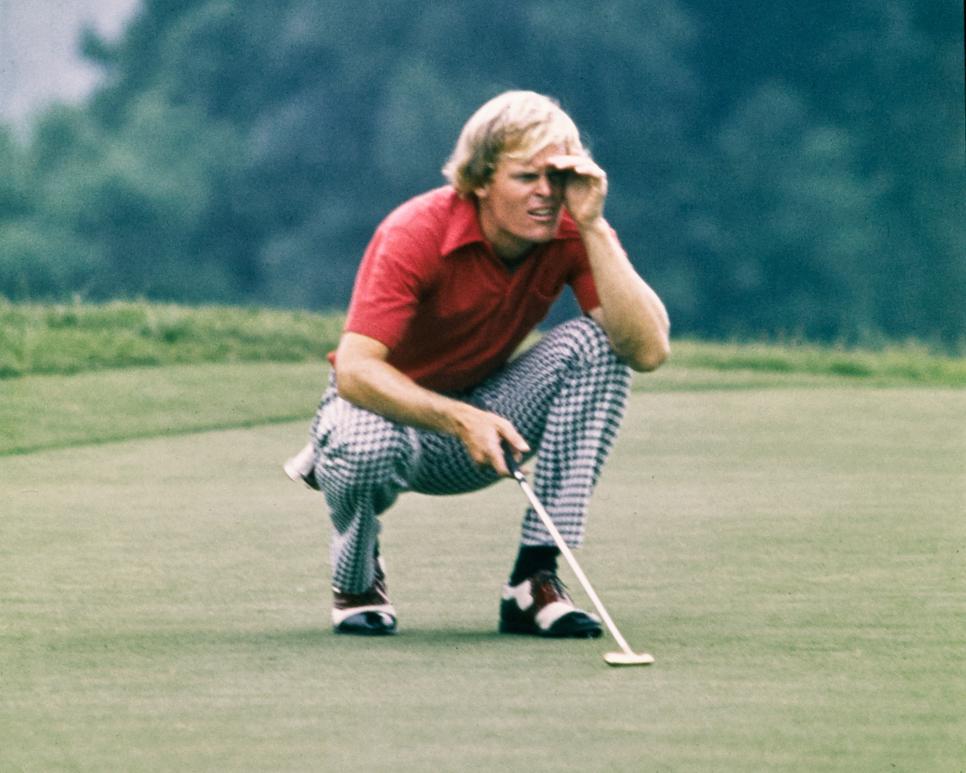

Johnny Miller has gotten a lot of mileage for the 63 he shot at Oakmont Country Club on Sunday at the 1973 U.S. Open. Critics of his television commentary tire of the rhetorical shoehorn he too often needs to mention the feat.

Maybe. But I think Miller deserves more credit.

On the toughest course in the toughest major championship, while coming from six strokes behind in the final round to win, Miller hit all 18 greens in regulation. He missed two fairways and had 29 putts, including a three-putt on the par-3 eighth hole. Nine of his full-iron approaches (three of them 4-irons) finished within 15 feet of the hole, four of them getting within six feet. In 2014, Golf World’s David Barrett, retroactively applying the PGA Tour’s “strokes gained” calculation, convincingly established that Miller’s is the greatest 18 holes ever shot.

Similarly, Miller’s round vividly illustrated and validated the sheer challenge of Oakmont. Even in major championships, many low rounds are shot, but few are remembered. But when a course is a true beast, the very rare near-flawless close by the winner deeply resonates. It’s why Ben Hogan’s 67 at brutal Oakland Hills in 1951 retains a mythic stature, and why Miller’s round endures. In golf, true ball-striking masterpieces are only painted against a canvas of extreme difficulty.

As he would prove from January 1974 through January 1975, when he won 10 tournaments, the last three by margins of eight, 14 and nine strokes, nobody in modern history could get hotter from tee to green than Miller. Although the perception that he has too eagerly agreed with this assessment has actually blunted Miller’s case. Even when he’s willing to share his unofficial title with Byron Nelson, no one notices.

"I never played bad as far as hitting the ball—literally always played well. It was never, Well, I played good today but might not play good tomorrow.”

Miller’s beginnings provided the potential for the ultimate round. His father, Larry, started Johnny in the game at age 5, hanging canvas tarps in the basement of the family home in San Francisco. There Johnny would hit for hours before a big mirror, Larry encouraging him to copy the positions in the pictures of instruction books by Sam Snead, Byron Nelson and Ben Hogan.

For his first three years, almost all of Miller’s golf consisted of a steady pounding of shots into the tarp. “That repetition got me used to hitting the ball in the middle of the face and recognizing the sound and that lack of vibration of perfect contact,” he says. “Hitting the ball solid became sort of automatic.”

Here Miller makes another seemingly outrageous statement that is actually quite reasonable, drawing a close comparison between himself and Tiger Woods.

“Tiger and I are the most familiar in background of all the great golfers,” Miller says. “We hit all those balls in the garage. Earl and my dad both played a very similar role, providing all those affirmations that we would be special players. Tiger was more possessed with the game than I was. But I always felt like we kind of share a bond, and that as a golfer I understood him.”

Like Woods, a strong sense of destiny guided Miller. “I knew when I was 8 years old that I was going to be a champion golfer,” Miller says. “From that time to well into my 20s, I never played bad as far as hitting the ball—literally always played well. It was never, Well, I played good today but might not play good tomorrow.”

Miller makes it clear he is not including putting. Brilliant on the greens as a kid, he lost the magic permanently when, while at BYU, he was told he habitually aligned to the left and tried to change. “I just got all screwed up and for the first time got yippy,” he says. Even as a PGA Tour rookie in 1970, Miller’s putting was suspect. But from the middle of the fairway, Miller accessed the gift he had grooved in his garage to hit the ball close more than his peers.

“I knew my iron play was better than anybody else,” Miller says. “Jack [Nicklaus] and [Tom] Weiskopf were incredible with the 1-iron, 2-iron, 3-iron. But 4-iron through the wedge, that was my forte. On an approach from the fairway I’d always think, I can beat this guy because my irons are better than his.

“Whether it was true or not, you have to believe it. You have to feel like something in your game is the best. Tom Kite and Gary Player believed they were the hardest workers. Or you think you’re extra smart, like Tom Watson. Jack and Tiger had a lot of things that started with their power. I thought I knew more about the swing than anybody. I became a student of impact—what the optimum positions were, a lot of it Hogan stuff—at a time when it seemed like no one was teaching impact. I focused on continuing the hit an inch or two beyond the ball after impact. I remember my dad always telling me that Rocky Marciano would say, ‘I don’t aim for their chin. I aim for the back of their head.’ ”

Miller refined his ideas further in the early 1970s after studying Gary Player hitting sand shots.

“Gary would get in an impact position at address. It helped my sand game, but then I thought, ‘What if I locked in my address position like that all the way down to the 5-iron?’ All of a sudden every iron shot went straight at the flag. That was a big turning point for me, because I knew I had an edge. All that study and work helped me feel like I deserved to win. And there is great power in that feeling.”

It all culminated in one moment in time at Oakmont. As you watch the world’s best take on what might still be the toughest course in the world this week—and very likely never sniff 63—give a nod, grudgingly, if necessary, to Johnny Miller.