News

What Golf Looked Like Before Tiger Woods Turned Pro And Changed The Game Forever

Photo by Getty Images

It is 53 weeks and counting since Tiger Woods last played a competitive round of golf. That is the longest stretch in which the most celebrated golfer in history, still recovering from two back surgeries undergone last fall, has spent away from the sport since before his famous coming-out party as a 2-year-old on the Mike Douglas Show. In the interim, the game has been left to ponder a question that’s paradoxically simple and complex.

What does a world without Tiger Woods playing professional golf look like?

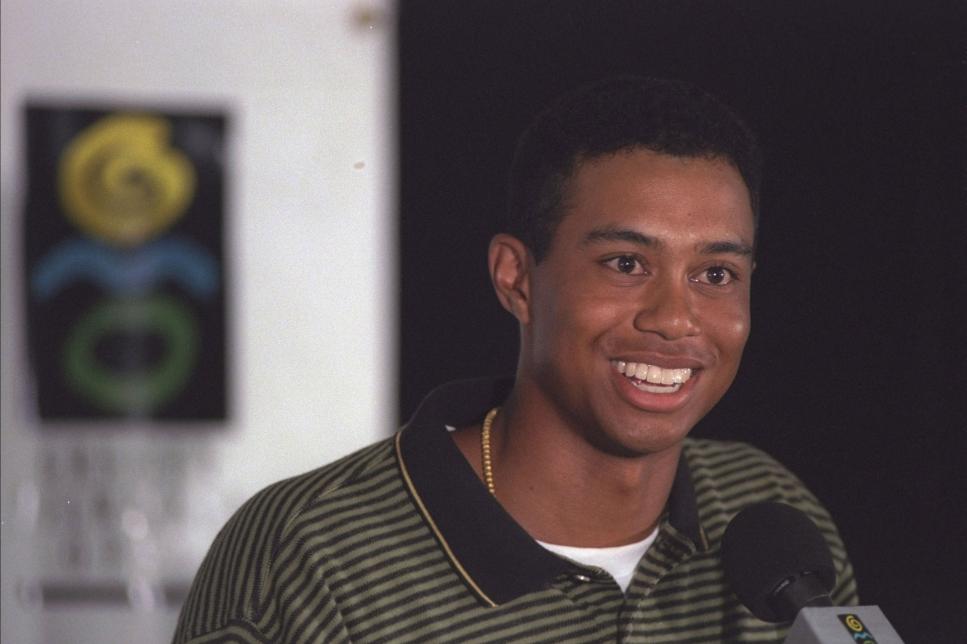

The last time anyone could answer that question intelligently was exactly 20 years ago, Aug. 28, 1996. Less than 72 hours after capturing his third straight U.S. Amateur title—in a third-straight come-from-behind victory in the championship match—Woods held a press conference at Brown Deer Park. From behind a three-foot-tall podium adorned with the PGA Tour logo, the 20-year-old Stanford undergrad announced he would be playing for a pay check that week in the Greater Milwaukee Open, competing on a sponsor’s exemption.

As it was at the time, it remains to this day the most anticipated announcement of a golfer turning pro, far greater than anything the game’s two other most distinguished amateurs ever endured. Of course, Bobby Jones never gave up his amateur status, and Jack Nicklaus did so only after considering a career selling insurance, leaving his decision to turn pro as much a surprise as it was a certainty.

Woods’ absence this last year has made for a brave new world in golf, but it remains one entirely shaped by Woods’ presence as the sport’s Northstar the previous 19. Golf is a radically different endeavor, both at the professional and recreational level, because of Woods and his 79 PGA Tour wins, 14 major championships, $110 million in on-course PGA Tour earnings and millions more off.

Arguably the best way to tell how different the game has become—and just what kind of impact Tiger has made—is by turning back the clock 20 years, to Aug. 27, 1996. What did the PGA Tour look like before Woods stepped to the podium and greeted cameras with a smile and a “Hello, world!” What did golf look like overall? It’s with this perspective that we can see how far it has come.

AP1996

INSTANT MILLIONAIRE

The anticipation of Tiger embarking on his pro career was, in part, bolstered by the unprecedented endorsement deals with Nike and Titleist that Woods announced before hitting his first shot at Brown Deer Park. Agents and industry observers had estimated that Woods would make around $15 million upon turning pro, an outrageous sum considering that players rarely signed endorsement deals without already having a PGA Tour card in hand. But the actually numbers dwarfed the predictions. Golf World reported that the Nike agreement was for an estimated $40 million—$6.5 million per year for five years with a $7.5 million signing bonus—to wear the company’s shoes and apparel. The Titleist arrangement was $3.5 million for three years to play the company’s clubs and balls.

Just how crazy were these figures? One agent contacted by Golf World said he knew of no other single endorsement contract in golf that paid even $5 million annually.

“What Michael Jordan did for basketball, [Woods] absolutely can do for golf,” said Nike chairman Phil Knight. “The world has not seen anything like what he’s going to do for the sport.”

THE WEEK BEFORE MILWAUKEE

It seems only appropriate (or perhaps ironic) that the closest rival Tiger would have during his pro career would be one of the last winners of a PGA Tour event in the pre-Woods era. On the same Sunday that Tiger won his third straight U.S. Amateur title, Phil Mickelson, 26, outlasted Greg Norman, with birdies on two of the last three holes at Firestone Country Club, to win the NEC World Series of Golf. (Later that afternoon Guy Boros also won the Greater Vancouver Open, the one and only title of the then 31-year-old’s career.)

Mickelson’s win let him jump Mark Brooks on the yearly money list, with $1,574,799 in earnings through 35 events in 1996. Here’s a snapshot of how the season was shaping up heading into Milwaukee.

PGA Tour money list (as of Aug. 28, 1996):

Phil Mickelson, $1,574,799

Mark Brooks, $1,359,537

Tom Lehman, $1,194,971

Mark O’Meara, $1,180,699

Steve Stricker, $1,119,139

Scoring average leaders:

Corey Pavin, 69.52

Mark O’Meara, 69.61

Tom Lehman, 69.69

Davis Love III, 69.74

Fred Couples, 69.79

Driving distance leaders:

John Daly, 286.6 yards

Davis Love III, 285.0 yards

John Adams, 284.2 yards

Tim Herron, 284.0 yards

Fred Couples, 283.7 yards

Greens-in-regulation leaders:

Mark O’Meara: 72.5 percent

Fred Couples, 72.2 percent

Tom Lehman, 71.1 percent

Rocco Mediate, 70.6 percent

Jesper Parnevik, 70.3 percent

Putting leaders:

Brad Faxon, 1.715

Mark O’Meara, 1.738

Kirk Triplett, 1.742

Nick Faldo, 1.743

Steve Stricker, 1.746

Most wins:

Phil Mickelson, 4

Mark Brooks, 3

Mark O’Meara, 2

John Cook, 2

Steve Stricker, 2

First-time winners in 1996: Tim Herron, Paul Goydos, Scott McCarron, Paul Stankowski, Steve Stricker, Willie Wood, Justin Leonard, Clarence Rose, Guy Boros

THE MAN EVERYBODY WAS CHASING

It had been an auspicious year for Norman, whose final-round meltdown at the Masters in April would once again characterize him as one of the history’s most snake-bitten golfers. Even so, the Shark, at age 41, was in the midst of a 96-week stretch atop the Official World Golf Ranking that began in June 1995, the longest streak of any golfer in the history of the ranking … until Tiger.

Here’s a look at the top 10 on the World Ranking as of Aug. 26, 1996:

FRONT RUNNER FOR ROOKIE OF THE YEAR

Having earned his PGA Tour card with a T-9 finish at PGA Tour Qualifying the previous December, Tim Herron needed just six tour starts in 1996 before he claimed his first victory, a four-stroke triumph over Mark McCumber at rain-soaked Honda Classic.

The then 26-year-old followed it with a top-20 performance the Players and three other top-15 showings through the summer. He was ranked 40th on the money list entering Milwaukee and looked to be the leading contender for the tour’s rookie of the year honor until Woods stormed through the end of the 1996 season, winning twice and qualifying for the Tour Championship. Consider it payback of sorts: Herron had defeated Woods in the second round of the 1992 U.S. Amateur, one of just three matches Tiger ever lost in a USGA championship.

MONEY BALL, PART I

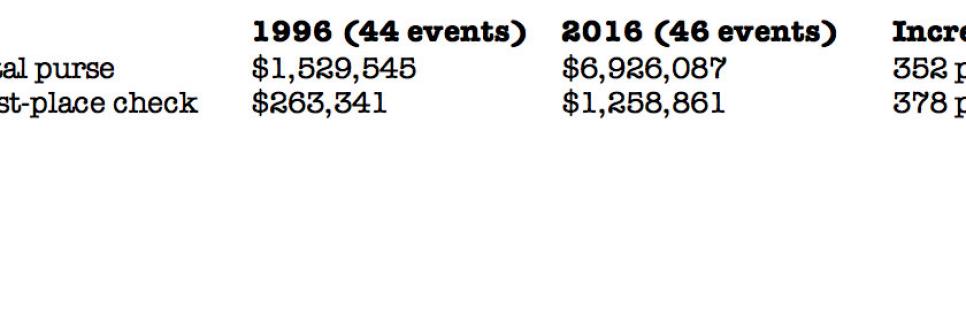

It’s often said that every golfer on the PGA Tour owes Tiger a thank you for what he did to increase the popularity of the tour and, in turn, bring sponsors and dollars that have trickled down to all players. Just how much of an influence did Tiger have on the financial well-being of the game? Consider the difference in how much money is played for in PGA Tour events in 1996 and today:

MONEY BALL, PART II

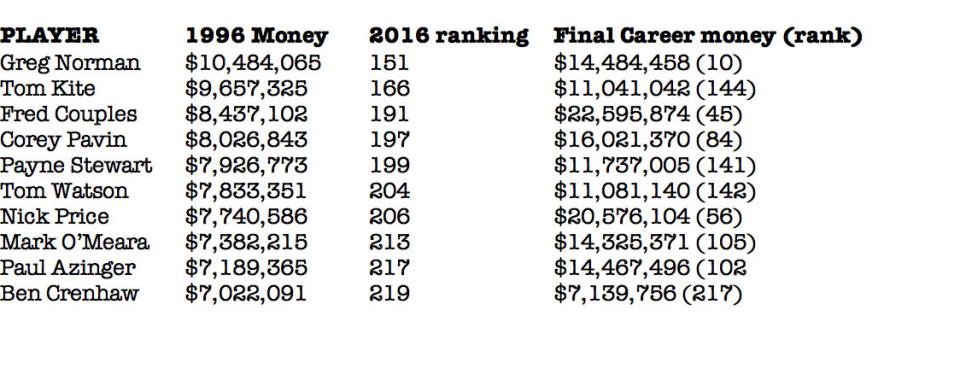

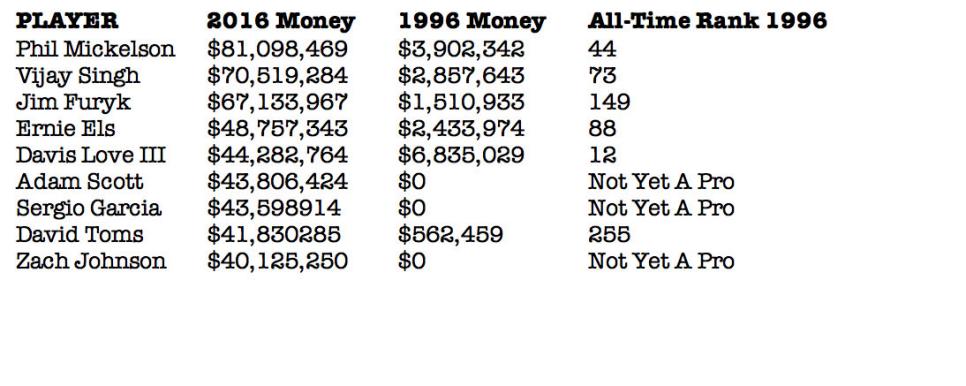

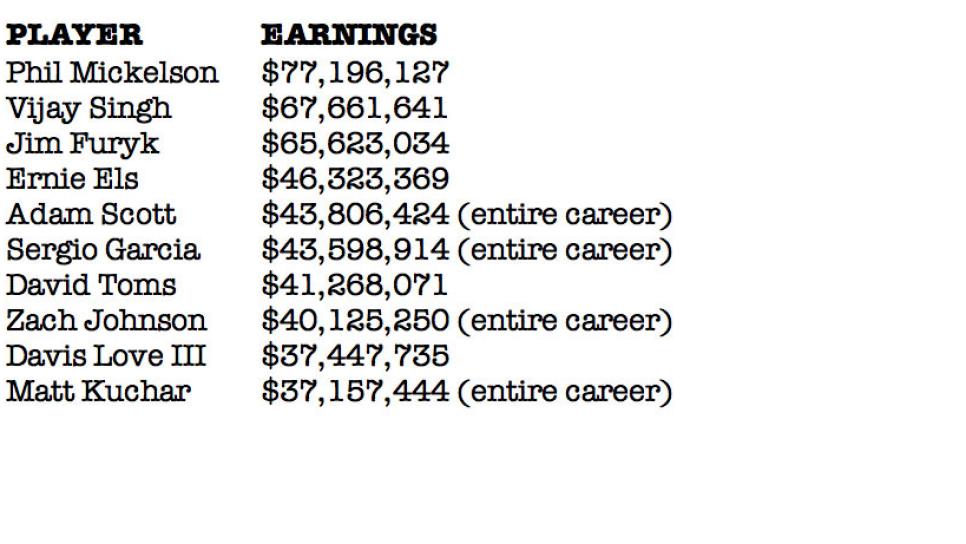

It’s crazy to look back at the all-time career money list from 1996 and not laugh at the scale of the numbers compared to today. At the end of 1996, there were just 10 golfers who had broken the $7 million mark in career earning. Today, 218 golfers have earned at least that much in their careers, with 157 players exceeding $10 million in career earnings.

Here’s another way to look at the exponential increase in money. Below is a list of the top 10 men on the career list at the end of the 1996. Next to them is where that same amount of cash would rank on the current all-time money list as of Aug. 28, 2016:

It’s also interesting to look at the current top 10 on the all-time money list to see where they were when Tiger turned pro.

And here is the top 10 in career PGA Tour earnings since Tiger turned pro (excluding Tiger):

IT’S NOT ABOUT THE MONEY, IT’S ABOUT THE VICTORIES

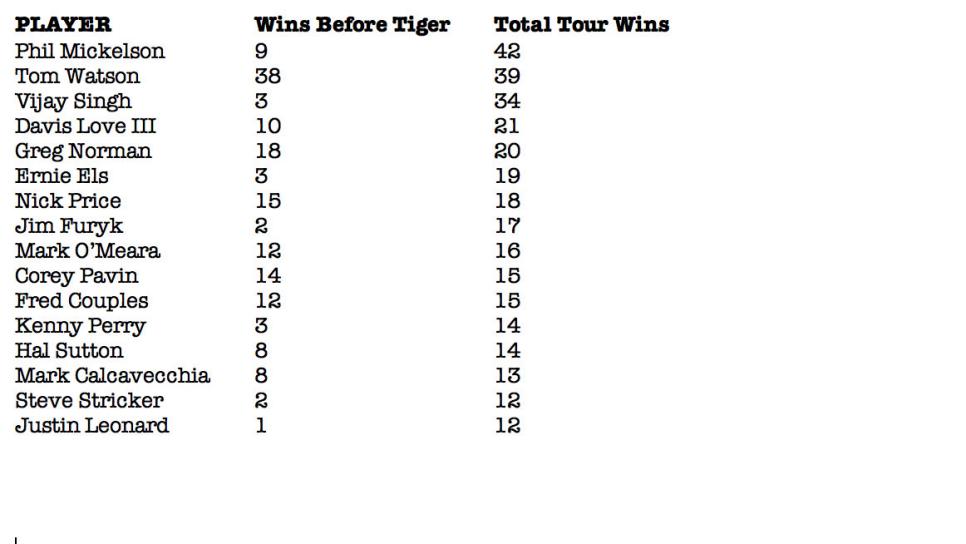

When Tiger turned pro, Tom Watson held the mark for the most career majors won by an active player with eight. Watson, then 46, also was the leader in most career tour wins overall by an active player at 38, having claimed victory at the Memorial only two months earlier. He would not win another major in the Woods era (coming so close in the 2009 Open Championship at Turnberry), but he would win one more tour title (the 1998 MasterCard Colonial).

As with career money, it’s interesting to look at where Tiger’s contemporaries stood regarding PGA Tour wins on the day that Woods became their professional rival.

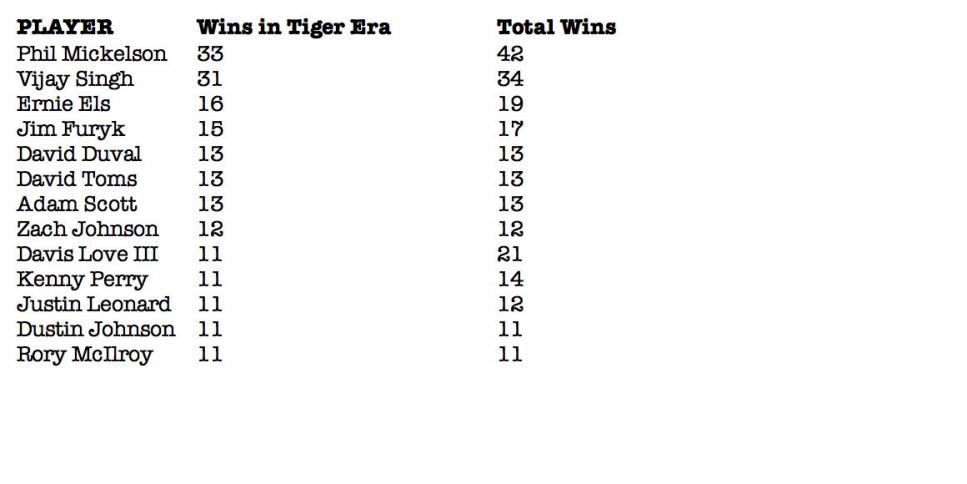

And here is a list of pros who have won the most PGA Tour events in the Tiger era:

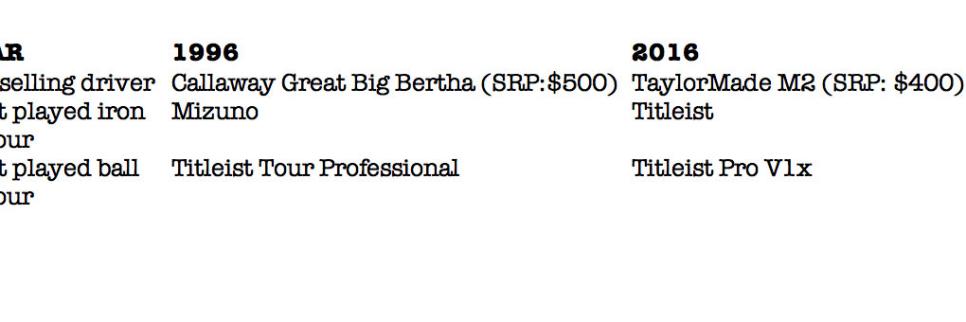

GEARING IT UP

It’s not like tour pros were still using persimmon drivers and gutta-percha golf balls in 1996, but the equipment innovations that fuel today’s market were still years away. Consider that the top-selling driver back in the summer of 1996 had a clubhead that was just 253 cubic centimeters in size compared to today’s 460cc giants. And the leading golf ball was built around a wound core rather than a multi-layered offering that maximizes distance, spin and feel.

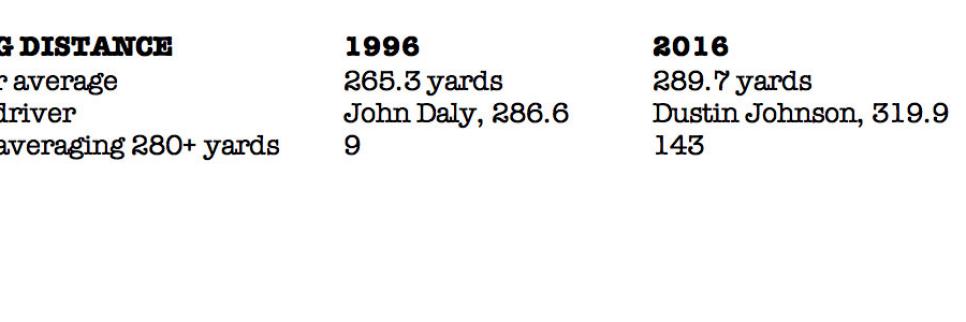

DISTANCE BOOM

While Tiger’s prodigious length caused many to marvel, this was one of the few instance where Woods did not solely create the rising tide that lifted all boats. Rather, improvements in equipment as well as the overall fitness of tour pros (something that Woods did inspire) best explain the massive increases in driving distance on the PGA Tour.

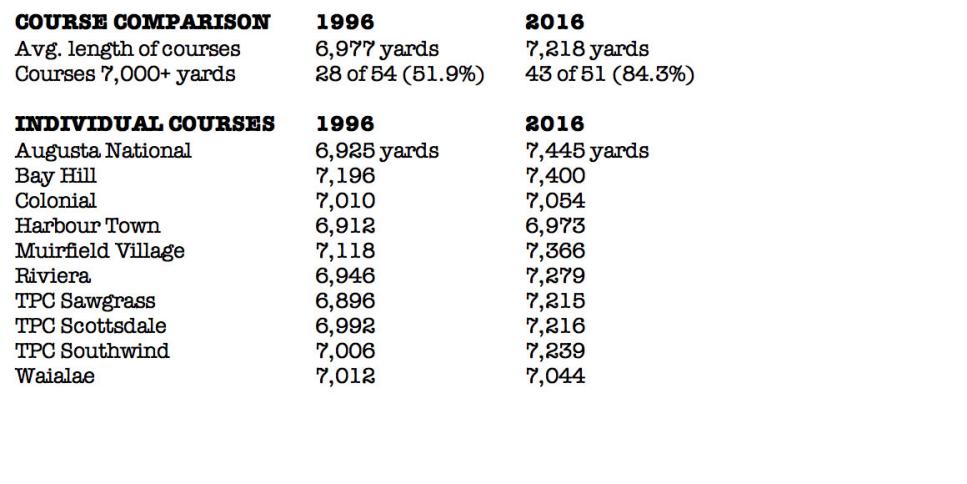

COURSES FOR HORSES

In turn, the places the PGA Tour visits have grown longer and bigger to accommodate today’s longer and bigger hitters. Here’s a comparison of course set-ups in 1996 versus the 2015-’16 seasons:

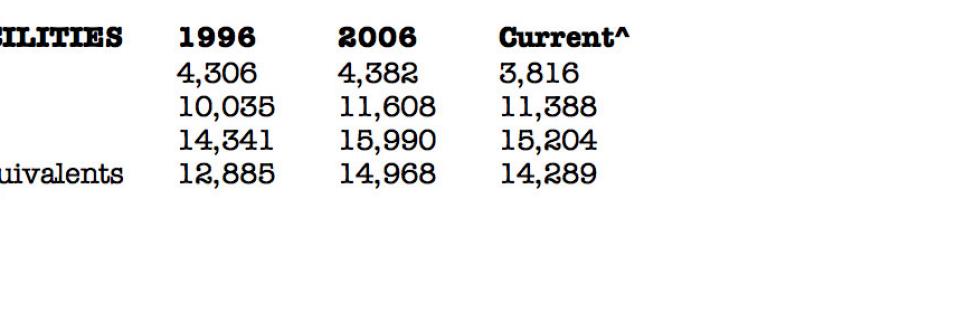

PLACES TO PLAY

The 1990s was already seeing a boom in golf-course development as real-estate ventures with access to a new course became popular investments. As Tiger helped increase the popularity of golf, the timing seemed almost perfect. In the last decade, however, a market correction has occurred with courses around the country closings due to too much inventory. Even so, the net number of golf facilities in the U.S. remains higher than it was when Tiger turned pro.

^ Most recent numbers from the National Golf Foundation are from 2015

IF YOU BUILD IT, WILL THEY COME?

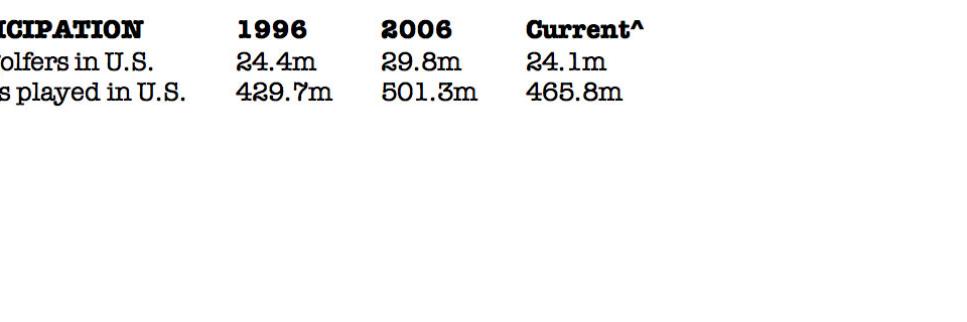

To say that many were counting on Tiger to become a pied piper for the sport as he made his first pro start would be re-writing history. Sure the potential was there, but it wasn’t until a year or so later, when Woods was a proven winner who brought golf from a tiny spot in the back of the sports page to front of the section—and even the front page of the entire paper—that predictions of a spike in participation were made in earnest. Yet for all those who presumed Tiger would bring the masses to the game, a handful also cautioned that Tiger’s star might attract short-term interest, but not necessarily long-term gains in participants, the numbers seem to bare out:

^ Most recent NGF numbers (in millions) are from 2015.

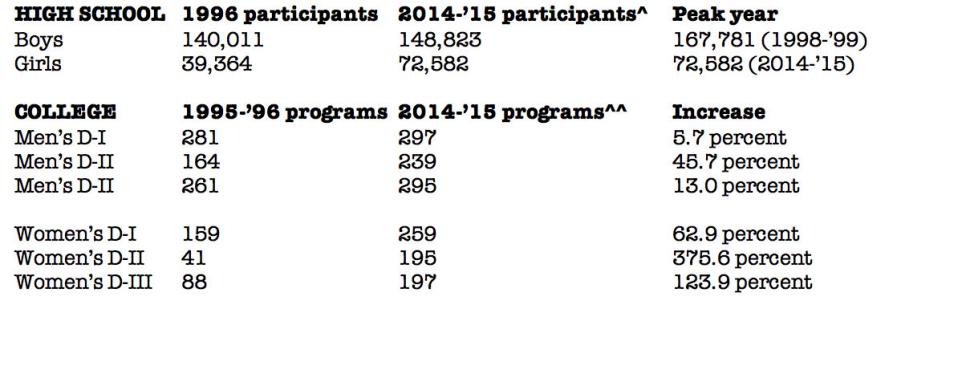

YOUTH IS SERVED

The stories about young boys and girls inspired to take up the game by Tiger’s win at the 1997 Masters or the Tiger Slam in 2000-’01 or any of his other achievements are numerous, with several current PGA Tour pros able to retell those very tales. Indeed, it would appear that if there has been a true bump in participation since Tiger’s pro debut, it’s most evident in the competitive junior and college ranks, where particularly in the girls’ game, the increase in interest is clear.

^ Latest National Federation of State High School Associations numbers are from 2014-’15 season.

^^ Latest NCAA numbers are from the 2014-’15 season.

Additional reporting from Joel Beall, E. Michael Johnson, Patrick Kiernan, Alex Myers and Mike Stachura.