Warning On Tiger: Fragile

Illustration by Eddie Guy

Editor's Note: This article appears in the October issue of Golf Digest.

Maybe it's all over. Odds are, it is.

So many key indicators say so: three recent backsurgeries/procedures, recurring chip yips, scores in the 80s, WDs, the quiet desperation in a muttered "C'mon, Tiger" before hitting a third straight pitch shot into the water.

In the history of golf, no great player who has fallen from the top for this long has ever returned to dominance. And no dominant player has ever dropped so far as quickly—from a record 683 weeks at World No. 1 (for periods from June 1997 to May 2014) to No. 683 in August 2016—as Tiger Woods.

The shock is still being absorbed. If the Woods era has truly ended, it will have happened at an age younger than any all-time player since Bobby Jones. Woods won his 14th major in 2008 at 32, but Jones' retirement from competition at 28 in 1930, like Byron Nelson's at 34 in 1946, was voluntary.

After looking as if he might have returned to his previous level after a 2013 in which he had five victories and won player-of-the-year honors, Woods has cratered. In the six major championships he has played since then—he didn't enter any of the four this year—he has missed four cuts. In the 64 he entered as a pro before that, he missed three.

The stark futility causes the mind to rebel. He's Tiger Woods, the most talented, grittiest, big-moment player ever. He can't go out this way. "He's done everything else," says Dr. Jim Afremow, sport psychologist and author of The Champion's Comeback, a study of the components and behaviors in the successful return of great athletes. "Coming back in a way that matches those other things is the only thing he hasn't done. It's why we can't stop talking about him."

No, golf can't quit Tiger Woods.

Perhaps it would be easier if there were more clarity, because for all the scrutiny and analysis, it's still impossible to know what exactly is the source of the problem with Woods. His words, always vague and withholding, seem intended to perpetuate avoidance and mystery. (Through a spokesman, Woods declined to comment for this article, but on Wednesday he announced on his website that he hopes to play in three tournaments this fall, starting Oct. 13-16 with the PGA Tour’s season-opening Safeway Open in Napa, Calif.)

His situation seems to be governed by three possible narratives:

INJURIES. Woods has had many of them, but we often have only his word as to where, when and how severe. Invoking injury as the cause of his poor play gives Woods control. He talks about it a lot, sometimes in detail. "The knee acted up, and the Achilles followed after that, and then the calf started cramping up," he said after withdrawing after nine holes at the 2011 Players Championship. After a two-month leave of absence last year, Woods played the worst golf of his career before a surprise back surgery in September and a sudden follow-up the next month. Throughout much of 2016, he stayed noncommittal and vague about the progress of his healing or any projections for a return to competition. "Put it this way: I want to play; I don't know if I will," Woods said in June of his chances of returning in 2016. The extended absence gave Woods a respite from the questions, scrutiny and judgment he was undergoing when he did play. It's also a more noble way to be inactive, a warrior hurt in battle. The promise of playing is one that his sponsors are attuned to, and so far, none have dropped him for non-performance.

Getty Images

‘Sure, there’s a part of him that wants to show the SOBs, but at the end of the day, at Tiger’s stage of life, that’s not enough.’ – Former swing coach Sean Foley

GOLF SWING. After years in which the progress of his most recent swing change dominated his post-round interviews, Woods has curtailed those conversations. It has always been more trouble to explain than injuries, with Woods tossing out jargon about "baseline shifts," "a consistent bottom," "explosiveness" and "feels" without elaboration before impatiently ending discussion with old standbys like "I'm close," or "It's a process." Woods talked about his technique a lot as he transitioned from Hank Haney to Sean Foley in 2010 and, since November 2014, "swing consultant" Chris Como. Each change has brought diminishing returns, which has added strain to interview sessions. The only time Woods welcomed talking golf swing was when it afforded him an explanation for his shocking chip yips, claiming the problems stemmed from getting "caught between" the different "release patterns" taught by Foley and Como.

PSYCHE. Presumably Woods' least-favorite narrative, based on the fact that he never talks about it. But it's impossible to ignore that even while factoring in his 2013 season, Woods' game has been in sharp decline since Thanksgiving 2009, when his Escalade hit a fire hydrant in front of his Isleworth home and sparked a humiliating scandal that cost him his marriage. The effect on his golf is impossible to quantify, but there is no doubt that the seemingly impenetrable fortress of mental strength that was perhaps Woods' biggest advantage over his peers has steadily crumbled. The chip yips that afflicted him in late 2014 and early 2015 were the biggest clue. After it seemed as if Woods had conquered them at the 2015 Masters, where he finished T-17, they reappeared four months later when he got on the fringe of Sunday contention at the Wyndham Championship, causing a triple-bogey 7 on the 11th hole. But the yips became secondary when Woods' game collapsed in May and June of last year, leading to an 85 at the Memorial and a cold-topped 3-wood while going 80-76 at the U.S. Open. The most awkward wedge moment for Woods occurred at a media day this year for the Quicken Loans National, which Woods hosts. Asked to take part in a casual contest (except that it was being televised live on Golf Channel), a 100-yard shot over a pond, Woods hit three consecutive balls in the water, each one successively more cringe-inducing. It was the last time for months that Woods put his swing on public display.

There's also a fourth possibility that becomes more obvious as time goes on for Woods—always scrutinized, always judged, the results never enough. Perhaps the man who golf can't quit wants nothing more than to quit golf.

REASONS TO QUIT

The signals of Woods being ready to let go have been there:

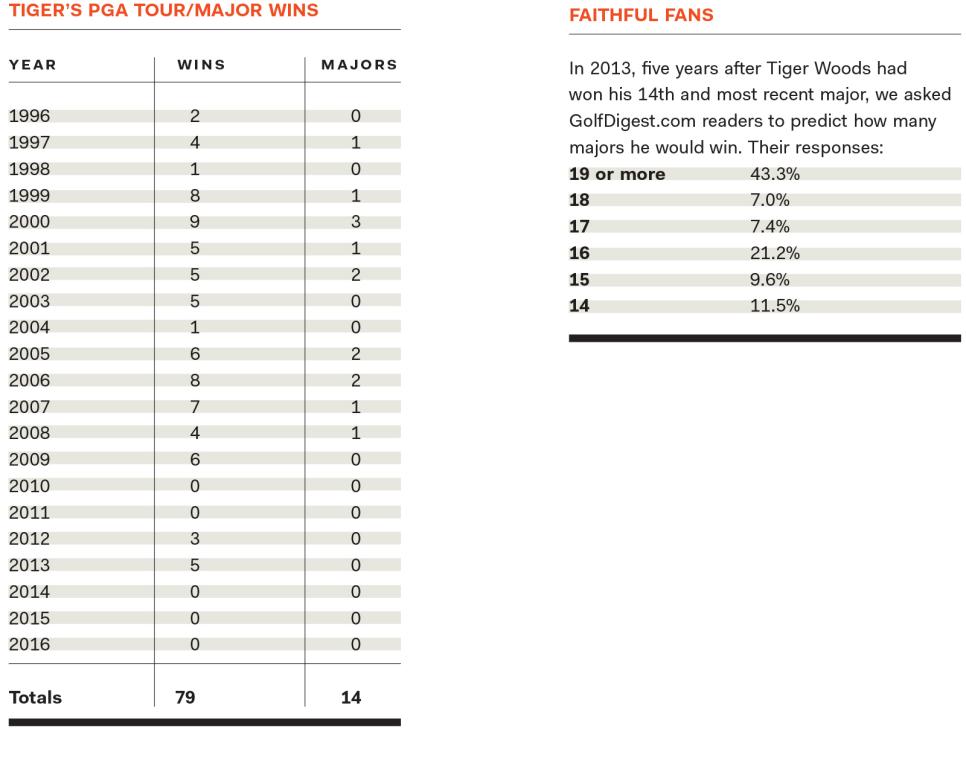

▶ He has taken on more of a "summing up" theme in his interviews, granting a long one to journalist Lorne Rubenstein for Time magazine last year. But the most pointed example occurred last December at the tournament Woods hosts in the Bahamas, the Hero World Challenge. Having not played competitively since August, a subdued Woods riffed about being OK with coming close to Sam Snead's career record for PGA Tour victories (82 to Woods' 79) and Jack Nicklaus' mark for major professional championships (18 to Woods' 14). "For my 20 years out here, I think I've achieved a lot," he said, "and if that's all it entails, then I've had a pretty good run."

▶ In June, Woods revealed that he will write a book about his landmark 1997 Masters victory, his first non-instruction book. It is to be released in March, co-written by Rubenstein.

▶ A downplaying of comparisons with Nicklaus, whose major record has been widely assumed to be Woods' ultimate goal. The first hint such might not be the case was an exchange from 2007 recounted in Haney's 2012 book in which the former swing coach asked "What about Nicklaus' record? Don't you care about that?" and Woods replied, "No, I'm satisfied with what I've done in my career." In the Time interview, Woods was adamant that he only ever measured himself against Nicklaus in terms of trying to achieve equivalent accomplishments at a younger age. "I beat them all. I beat them all," Woods said with emphasis. With the possibility of Woods surpassing Nicklaus' record growing increasingly remote, such a characterization takes some pressure off.

▶ Mentoring Jason Day by inviting questions and not censoring Day from revealing the content of his text messages.

▶ Accepting the position of vice captain on the U.S. team for this fall's Ryder Cup.

▶ Putting an emphasis on time with his two children, Sam Alexis, 9, and Charlie Axel, 7. When asked about the possibility that he might not play again, he told Time, "With all my heart, I do not want to stop playing golf. But the flip side is, my kids' lives are much more important to me. Now, if I can do both, that is an ideal world. It's a win-win. If I can only do one, it wouldn't be golf. It would be my kids. That's still a win-win."

That's all legitimate fodder to support the thesis that Tiger Woods could be done. But now Woods says he wants to come back. How would that work?

No doubt he derives motivation from the chance to prove his critics wrong. "Sure, there's a part of him that wants to show the SOBs," Foley says, "but at the end of the day, at Tiger's stage of life, that's not enough. To commit to what it will take, his reasons will have to be deeper than that."

Woods has said as much. In a film series commissioned by the R&A titled "Chronicles of a Champion Golfer," he explained that his efforts to win the 2006 Masters, which he knew would be the last major his father, Earl, would see him play, fell short because "I played for the wrong reasons. . . . I played for someone other than myself." Woods said that afterward, his father told him, "Never do that again. You play golf for you." Woods added, "It has to come from within. It can't come from outside."

Michael Phelps began to find self-fulfillment through rededication to his sport during his 45 days in an Arizona rehabilitation clinic after his DUI arrest in the fall of 2014. The Olympic swimming champion says he had suicidal thoughts because of the public humiliation but emerged a happier, more open person who rediscovered joy in training. At the Rio Summer Games, Phelps, 31, won five gold medals and a silver while becoming closer to his teammates and friends.

"Michael had all the medals before this year; he was already the greatest Olympian," says Haney, a friend who coached Phelps in golf on TV's "The Haney Project" and is his neighbor in the Phoenix area. "But that didn't make him a happy, healthy person. He wasn't a bad guy, but he usually seemed distracted, not always there. As he went through treatment, he wanted to redeem himself and overcome his issues. He got a very clear purpose about that, and he became a different person. And the extra focus made him an even greater athlete."

‘The big thing is, he has to stop trying to play like the Tiger Woods of 21... Use what you have now.’ – Former heavyweight boxing champion George Foreman

An even longer and more unlikely journey of self-discovery was at the heart of arguably the greatest comeback in sports history, George Foreman regaining the heavyweight title at 45, more than 20 years after he'd lost it to Muhammad Ali in 1974.

Undefeated in 40 previous fights, with a string of quick knockouts longer than what Mike Tyson would attain, Foreman had been the overwhelming favorite to defeat an aging Ali in Zaire. After Ali knocked him out in the eighth round, Foreman was a broken man.

"I was humiliated, ashamed, embarrassed—all of the above," Foreman says from his home in Houston. "And when you're the undefeated champion, recovering psychologically from a defeat like I had is a very hard thing to go through. I lost a part of myself, and it took me a long time to get it back."

Foreman became reclusive. His next fight, a slugfest with Ron Lyle in which Foreman was knocked down twice before desperately managing to knock out Lyle, felt like a flashback. "When I was on the canvas against Lyle, I thought, Oh, it's happening all over again. I'm nothing," Foreman says. Three years later, after losing in an upset to Jimmy Young, Foreman left boxing. He became a preacher in Houston and wouldn't fight again for a full 10 years.

On his way to winning the championship the first time, Foreman had assumed a persona of glowering bad guy, borrowed from early mentor Sonny Liston. After becoming a preacher, Foreman allowed his natural gregariousness to emerge as he openly shared the lessons of his life. "I had carried a lot of hate," says Foreman, who grew up in Houston's slums. "I decided I wanted to be liked, and to be liked, you have to like." He sought out people he had mistreated in his boxing career and apologized. "I had a lot less money," he says, "but for the first time in my life I was happy."

Foreman began boxing again to support a financially strapped youth center bearing his name. His comeback was met with derision. "Basically, the critics were right," he said. "All you have to do is look at the history of boxing. But the one place I was different from the other champions who came back is that I didn't start back at the top with the big stuff. I started from the bottom with club fighters. Nobody had ever done that."

For several years, Foreman fought progressively better opponents, taking joy in improving at his craft. But he also found that age had taken away some of his speed. "The original George Foreman, I never did recapture that timing. I couldn't do it my old way anymore, beating guys to the punch and knocking them out in the first round, and I had to accept that. If I wanted to be heavyweight champion of the world again, I would have to perfect things that I had never done before." He studied film of older fighters, like his trainer, Archie Moore, and saw a more economical style that saved energy with minimized movement and emphasized precision and patience over power.

Foreman is not a golfer, though he shared conversations with Sam Snead when the golfer, in his 70s at the time, visited his training camp. "He supported my comeback, telling me how he'd stayed competitive even when he couldn't be the Slammer in the same way," Foreman says. "Tiger has to figure out some of the same things I did. He's had some shame and humiliation. He did a lot of things that a lot of athletes do; he just got caught. But I think he's gotten up, or will get up from that. The big thing is, he has to stop trying to play like the Tiger Woods of 21. There's an edge he's going to have to give up. Don't try to go back and get what you used to have. Use what you have now. He can still be great, because that's still inside him. Even after I changed my style, the inside of me never changed."

Of course, Tiger has other complications that Foreman didn't. Woods is a natural introvert who isn't comfortable sharing his feelings. And the idea of him easing his way back in obscure tournaments wouldn't fly for the golfer whose every shot, even on the practice tee and at clinics, is on camera, subject to critiques. Most important, Woods is fighting injuries that have the potential to end his career.

As a younger man, Woods had a history of returning too quickly after his surgeries, seemingly using the swiftness of his recovery to send yet another message of superiority to his rivals. The 2014 book Blood Sport reported that after season-ending knee surgery in June 2008 and a right Achilles-tendon injury that resulted from his aggressive rehab, Woods had 14 sessions of blood-spinning therapy with Canadian sports doctor Anthony Galea, who in 2011 pleaded guilty to smuggling human growth hormone and other unapproved substances into the United States to treat pro athletes. The book also reported that an associate of Galea's visited Woods 49 times from September 2008 to October 2009. Woods and Galea have said that Woods received only legal platelet-rich plasma therapy.

US PGA TOUR

PAIN, STRESS LEVEL AND PSYCHOLOGY

Although the time needed for lower backs to heal depends on the individual, the consensus is that physical activity can be resumed after 12 weeks. However, with Woods waiting more than a full year to play again, his agent, Mark Steinberg, says that Tiger has "not considered or is planning to consider" whether psychological factors could be responsible for the physical symptoms.

There is much research providing evidence that tension from unresolved repressed emotions—particularly anger and shame—can be an important source of chronic pain. According to work pioneered by Dr. John Sarno, a now-retired professor of rehabilitation medicine at NYU, the body's reaction to deep psychological wounds can be to create physical pain to prevent hidden emotions from becoming conscious. Sarno calls this Tension Myoneural Syndrome and says that such psychosomatic pain that can't be traced to actual structural changes often occurs in the back.

Afremow, the peak-performance coordinator for the San Francisco Giants, says he often sees variations of the syndrome at work in competitive sports. "Especially with top athletes, pain can be a barometer of their stress level," he says. "Men especially tend to bottle everything up, and this is more true for the highest achievers, who are used to pushing through everything. It can result in constant pain, without any physical sign. The mind-body connection has been underestimated."

Some close to Woods worry that he carries tension born of anger and regret. His friend Michael Jordan, who made a successful comeback to basketball after retiring for a season to play pro baseball after the death of his father, told Wright Thompson of ESPN The Magazine that Woods continues to suffer from the fallout of his infidelities. "That bothers him more than anything," Jordan said. "It looms. It's in his mind. It's a ship he can't right, and he's never going to. What can you do? The thing is about T-Dub, he cannot erase. That's what he really wants. He wants to erase the things that happened."

Afremow says that successful athletic comebacks are built first by releasing—generally with professional help—the "mental brick" of emotional conflict that can impede motor skills, concentration and energy.

‘Whatever the issues, he has to give himself permission to be great again. As a golfer, he’s got some time.’ – Dr. Jim Afremow, sport psychologist

"Tiger's case would probably be more complicated because it was so painfully public," Afremow says. "But whatever the issues, he has to give himself permission to be great again. As a golfer, he's got some time. If he can recover his game, it would make him the most prominent figure on the Mount Rushmore of comebacks."

To call it a long shot would be an understatement. Yet what if—beginning with the ultimate sabbatical—a healed and refreshed Woods could still access his most distinguishing gift: the uncanny ability, in the sport with the smallest margins for error, to get it done?

If he truly wants to return, maybe what has proved the hardest challenge of his life is still doable.

Woods turns 41 Dec. 30. The oldest winner of each major, and selected others:

MASTERS

Oldest: Jack Nicklaus, 46.

Selected others: Ben Crenshaw, 43; Gary Player, 42; Mark O'Meara, Sam Snead, 41; Ben Hogan, 40; Snead, Angel Cabrera, Phil Mickelson, 39; Hogan, Player, Nick Faldo, 38.

U.S. OPEN

Oldest: Hale Irwin, 45.

Selected others: Julius Boros, Raymond Floyd, 43; Payne Stewart, 42; Nicklaus, 40.

OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP

Oldest: Old Tom Morris, 46.

Selected others: Robert De Vicenzo, 44; Mickelson, 43; Darren Clarke, Ernie Els, 42; O'Meara, 41; Henrik Stenson, 40; Player, Zach Johnson, 39; Nicklaus, 38.

PGA CHAMPIONSHIP

Oldest: Julius Boros, 48.

Selected others: Lee Trevino, 44; Vijay Singh, 41; Nicklaus, 40; Floyd, Larry Nelson, 39; Hubert Green, 38; Jimmy Walker, 37.

AGE WHEN WINNING LAST OR MOST RECENT MAJOR

Selected players

48: Julius Boros

46: Old Tom Morris, Jack Nicklaus

45: Hale Irwin

44: Harry Vardon, Roberto De Vicenzo, Lee Trevino

43: Raymond Floyd, Ben Crenshaw, Phil Mickelson

42: Gary Player, Payne Stewart, Darren Clarke, Ernie Els

41: Sam Snead, Mark O’Meara, Vijay Singh

40: Ben Hogan, Henrik Stenson

39: Larry Nelson, Angel Cabrera, Zach Johnson

38: Hubert Green, Nick Faldo

36: Walter Hagen

34: Arnold Palmer

33: Gene Sarazen, Byron Nelson, Tom Watson

32: Tiger Woods

31: Seve Ballesteros