News

Slow Play's Darkest Day

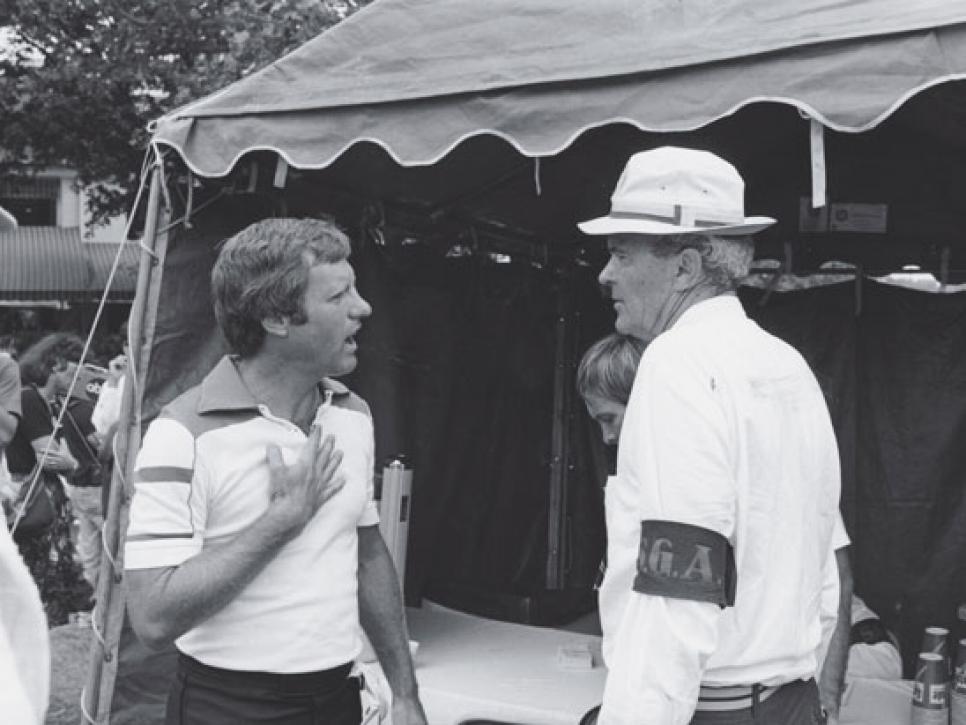

THE CONFRONTATION: John Schroeder argues his case with the USGA's P.J. Boatwright.

In the end, as it always is, slow play is about perception.

So it was more than three decades ago, the last time the U.S. Open came to Merion, in what is believed to be the first and only time a slow-play penalty was rescinded in the championship's history. One of the two victims that day--or benefactors--was John Schroeder, long labeled one of golf's slowest players.

"I'm not ever going to deny that I was a slow player," he says. "I know who I am. But in this case, we were unfairly accused. I don't mind taking a stand against slow play, but to me in this particular situation there were extenuating circumstances."

Extenuating circumstances always seem to be at the center of any slow-play situation, and though neither side seems particularly in the right, what happened at Merion in 1981 says a lot more about who really sets the pace-of-play culture in golf than it does about how rules-makers, even perhaps the most respected rules expert in the game's history, could ever hope to contain--let alone cure--the full-blown pandemic that has become golf's glacial pace of play.

The USGA has announced a campaign to improve golf's pace of play, and president Glen Nager called slow play "one of the most significant threats to the game's health" in his annual address in February. He also noted that the USGA Research and Test Center is developing "the first-ever dynamic model of pace of play." But science is theory, and intent is admirable. In the real world, it's hard to overturn the excessive deliberation that today seems as much a part of golf's culture as short pencils. The penalty against 14-year-old Tianlang Guan at this year's Masters showed that slow play remains a judgment call few are willing to make.

'YOU'VE GOT TO BE KIDDING ME'

Of course, unraveling the details of the Merion episode is like watching "Rashomon" in the original Japanese. The details begin when the threesome of Schroeder, Forrest Fezler and John Brodie (the former NFL quarterback and future senior-tour player) finished their second rounds of the 1981 U.S. Open approximately 20 minutes behind the group in front of them. As they entered the scorer's tent, P.J. Boatwright, the USGA's executive director and its top rules official, approached Schroeder and Fezler and informed them they were both being penalized two strokes for violating what was then Rule 37-7, which required a golfer to play without "undue delay." Boatwright, a roving official with specific responsibilities for pace of play, had been monitoring the group for much of the back nine. Schroeder and Fezler were inside the cut line, and Schroeder had just finished with a second-round 68, which put him near the top of the leader board.

"I said, 'You've got to be kidding me. That's not reasonable, not reasonable at all,' " Schroeder says now, the fire still in his voice--though he insists he's not bitter, that playing in that Open did a lot of good things for his career, including getting him into the Masters and the next year's Open, where he was able to do television work that would lead to a second career.

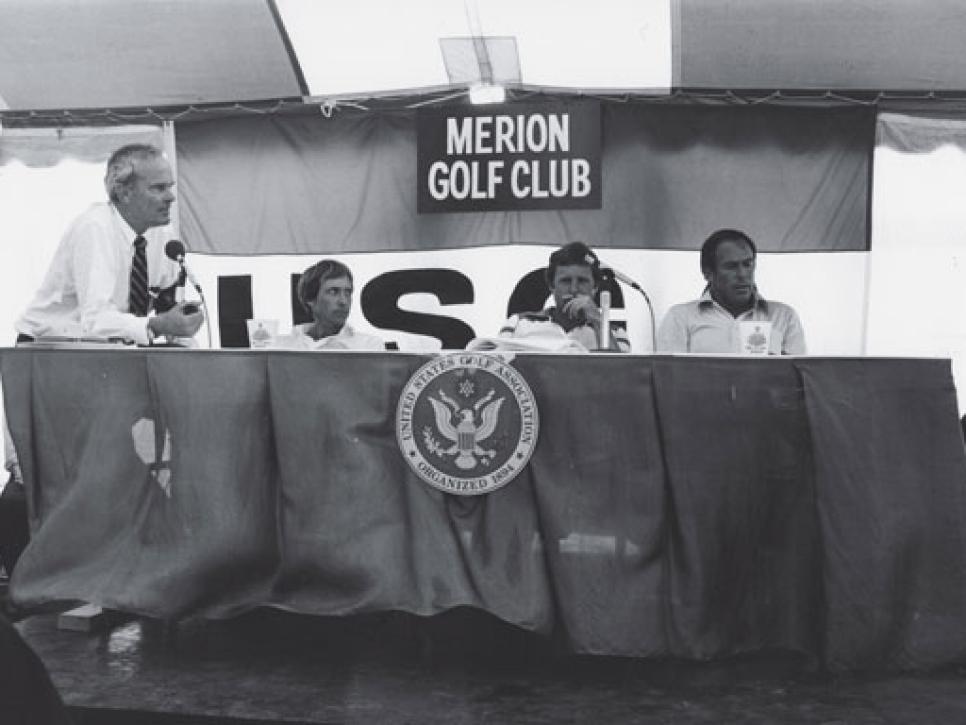

In unprecedented fashion for the U.S. Open, Schroeder was granted an appeal of the penalty to the USGA's Special Rules Committee, which in addition to Boatwright included Will Nicholson, USGA president; Jim Hand, USGA vice president; and Bill Williams, USGA secretary.

The confrontation was a contrast in styles, to say the least. Boatwright, the genteel, yet exceedingly meticulous interpreter of the rules, was calm and direct; Schroeder and Fezler were aggravated. (Schroeder had finished bogey-bogey, and Fezler, who still politely declines to speak on the record about the incident, had nearly lost a ball on the 16th hole.) And they were vocal. As one report had it, Schroeder and Fezler went "beyond the 'dadgum' stage" during the meeting. (Fezler is perhaps better remembered for the 1983 Open, when he ducked into a portable toilet near Oakmont's 18th tee and finished the final round in shorts.)

The minutes of the 1981 appeal were never made public, but several key elements apparently gave the committee room to reconsider Boatwright's penalty. Chief among them was Brodie's pleas to the committee after shooting an 82 with two lost balls. Although he wasn't penalized, Brodie, who was unavailable for comment for this story, took full share of the blame at the time: "I had my ball in some weird spots. Sometimes I needed four shots for every one of theirs." Brodie's stature as a former NFL star and TV broadcaster also might have helped. "If John hadn't come in and testified on my behalf, I'd have been sunk," Schroeder says.

Boatwright, who died in 1991, saw it differently. "I recognize that a player playing in the Open is under strain," he said that day. "But I thought they were taking too much time. What really convinced me, after I thought it through, was the fact that they must have known when they got to the 17th hole that they were way behind."

But it gets even more complicated than he said/he said. As then-USGA secretary Williams remembers it, "Back in those days, the policies relating to imposition of the slow-play penalty were not as detailed as they are now."

There is another theory that the committee also considered whether players should be informed promptly after they incurred the penalty rather than waiting until after the round--the thinking being that it would be unfair for a player trying to make the cut or even leading the tournament with two shots in hand to play the final hole conservatively, only to be hit with two shots after finishing his round.

Schroeder was appealing the penalty in much the same fashion that Gary Player successfully overturned a slow-play ruling less than a year earlier in the PGA Championship: by saying it wasn't his fault.

In the end, the committee voted 3-1 to rescind Schroeder's penalty, Boatwright being the only vote to uphold the two strokes. "There was enough doubt in our minds," Hand said at the time, referring to the lost balls specifically. "We felt, as a committee, that we should support the players' view."

Williams remembers the decision being unpopular across a wide constituency, especially fellow officials who suggested Boatwright's authority had been completely undercut. "It was awful," he says today. "Everybody was up in arms because Schroeder was known to be a slow player. Everybody was sorry for P.J. Some people even told P.J. he should quit the USGA.

"He was really hurt by it for a while, which was unfortunate. But time puts these things out of your mind. We felt badly about it, too."

Though Schroeder believes he was unfairly targeted because of his reputation and was an easy mark ("There's a bias to make examples of no-names--the stars never have a problem," he says), Hand dismisses that idea. "P.J. didn't have a malicious bone in his body," he says. "He was a real stickler by the rules, but he was always fair. I can't imagine him ever deciding that, 'Well, he's a notoriously slow player, so we'll get him.' "

Still, it appears the slow-play procedure clearly became an issue of concern, so much so that in the minutes of the USGA annual meeting the following January, a new warning system was discussed so "the players in a slow group might be advised that they are out of position or asked to explain why they are out of position."

TWO SLOW-PLAY PENALTIES IN 32 YEARS

In the ensuing decades, the policy ofofficially warning players several times before imposing a slow-play penalty was installed, but play throughout professional golf only ended up getting slower. Among the most commonly cited culprits: players beginning elaborate pre-shot routines only after a playing partner has hit, long strategy discourses with caddies, and increasingly diabolical green speeds that cause players to mark before attempting even the shortest of putts. Even with a procedure in place, penalties have cropped up in the rarest of circumstances. It's believed that there have been only two slow-play penalties issued at the U.S. Open since Merion. One came in 1987, when Sam Randolph, near the lead in the second round, was penalized two strokes in the middle of the 18th fairway; the other came in 1997, when Ed Fryatt was penalized in the second round. It's no different in non-majors: Since 1992, there have been only two slow-play penalties imposed at regular PGA Tour events.

More commonly, players are warned or informed that they are on the clock. It happened to Payne Stewart at Olympic in 1998 in the final round when he was in the final group. And at Olympic last year, Jim Furyk and Graeme McDowell, playing in the final group, twice were warned about slow play. But in neither case was a penalty imposed.

The Open even adopted a two-tee start beginning in 2002 with the idea that it would provide an extra two-hour window to accommodate weather delays, but it really was an admission that getting 156 players through a round of golf on the longest days of the year had become too problematic. Given today's early-round slogs, it's remarkable that as late as 1948 there were as many as 170 players in a U.S. Open's opening rounds.

As former USGA senior executive director Frank Hannigan rightly notes, whether they be at major championships or run-of-the-mill tour events, penalties are not a priority: "U.S. Open pace of play stunk before Schroeder and after Schroeder. I vividly remember the first five-hour round in the history of the USGA took place at Bellerive in 1965.

"The tour does not have a slow-play problem, because it has had no effect on its revenue," Hannigan adds. "If it did, they would have fixed it long ago. So it's unrealistic to expect play at Opens to be better than on tour unless you want to make penalties the only story of the week, which nobody has the [guts] to do."

"I don't think we ever felt we really got a handle on it," Hand says today. "The effort was always to get the attention of the players that the threat was hanging over their heads, so therefore they ought to try to pick it up. But it's a very difficult thing. It's a judgment call."

Current USGA executive director Mike Davis believes it's a more complicated issue than penalties alone can resolve. "The behavior of players themselves is not the only cause of slow play, and in fact might not be the primary cause," he said in an email to Golf Digest, indicating course setup, hole locations and green speeds might matter as much. "So, while player behavior is a factor, facilities and championship administrators play a more meaningful role to mitigating slow play."

Even Schroeder is baffled by what he sees on TV: "People say I was slow, but you watch how long it takes them to play a shot today? It's a joke."

He might be right. In 1981, that glacial, rule-breaking pace of Schroeder, Fezler and Brodie? Exactly four hours, 20 minutes--17 minutes faster than the recommended pace of play for a threesome at last year's U.S. Open.