News

Defining Moment

Photographing a golf tournament can be hot, sweaty work or cold, rainy work, the creative payoff rarely equaling the physical exertion. Golf is the rare sport in which the person behind the camera moves around as much as his subject, five miles or more, depending on the design of the course and plot of the leader board. Marshals, cap brims, television cameramen and signage can sabotage a composition, not to mention phlegmatic players who greet a spectacular stroke with a shrug.

I photographed 40 or so major championships during the 1980s and 1990s, so I speak from the experience of having captured thousands of ordinary moments, several dozen very good ones and a couple that golf aficionados, if pressed, might even remember. Larry Mize breaking Greg Norman's heart at the 1987 Masters, and Costantino Rocca rousing all of St. Andrews at the 1995 British Open come to mind. So does the sad double-chip by T.C. Chen at the 1985 U.S. Open, where his wedge, waist-high, is striking the ball a second time. Sometimes, all the effort was worth it.

For anyone who has photographed much golf-tournament action in the last half century — I think of a talented cadre including David Cannon, Darren Carroll, J.D. Cuban, Dom Furore, Scott Halleran, Rusty Jarrett, Leonard Kamsler, Brian Morgan, Jim Moriarty, John Mummert, Stephen Szurlej, Fred Vuich and the late Phil Sheldon — the bar for excellence was set extremely high before most of us were even born.

I scarcely went out on an assignment without thinking about what Hy Peskin achieved on June 10, 1950, and I doubt my contemporaries have either. Peskin's image of Ben Hogan — just 16 months removed from a car accident that nearly killed him, playing his approach with a 1-iron to the 18th hole during the fourth round of the U.S. Open at Merion GC — is a masterful study of a legend.

"At boarding school, other kids had semi-nude girls or Rod Stewart on their walls," says Cannon, a veteran British photographer for Getty Images. "I had Tony Jacklin and Tom Weiskopf and that Hogan photo. Years before I started taking pictures in the late-1970s, I knew that one."

Golfers know it the way we know Francis Ouimet and Eddie Lowery walking toward an upset victory at the U.S. Open in 1913; Bobby Jones (1927) and Seve Ballesteros (1984) triumphant in St. Andrews; Arnold Palmer exuberantly finishing off his lone U.S. Open win at Cherry Hills in 1960; Tom Watson chipping in at Pebble Beach in 1982; Jack Nicklaus turning back the clock at Baltusrol in 1980 or Augusta National in 1986; Payne Stewart's unbridled joy at winning the 1999 U.S. Open; Tiger Woods reacting after somehow finding a way to get it done on the 72nd green of the 2008 U.S. Open.

Yet Peskin's photograph of Hogan stands out from the rest, a peerless merger of "technical excellence and historical significance," as summed up by my friend and former golf photographer, Larry Petrillo.

"To me, it is the most famous picture in golf history. It's a magical picture," says legendary sports photographer Walter Iooss Jr. "A lot of times, history goes by and makes something interesting. Other times, it was a moment that was perfectly captured. Peskin's Hogan shot is one of them. It just has everything, and that's what makes a picture stand out and stand the test of time. It's like the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima. It's a picture everybody knows."

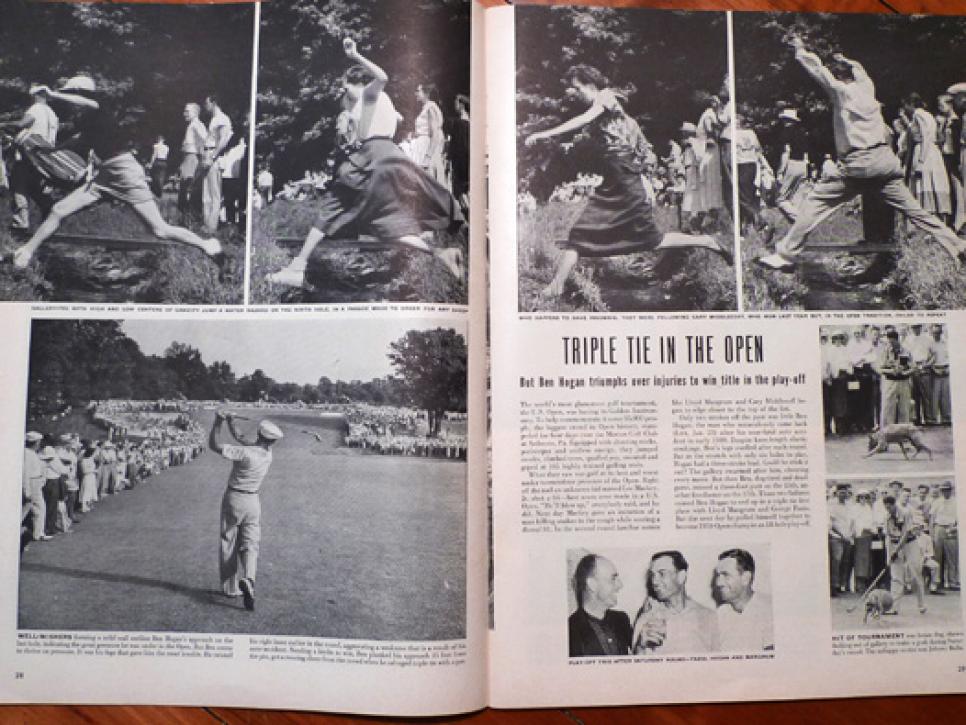

Peskin's Hogan photograph was originally published in the June 19, 1950 edition of Life magazine, amid stories about gambling in America, the thoroughbred Citation and a plane crash in the Atlantic Ocean that killed Puerto Rican farm workers. The cover story, "Children's Sand Styles," was a pictorial about swimsuits for little girls. There were advertisements for Ipana toothpaste, A&P super markets, Lucky Strike cigarettes and Armour pantry-shelf meats. Hogan was featured in an ad for Pabst Blue Ribbon beer on page 112 — "Ben's nose is teased by the delicate and inviting fragrance of the finest malt and hops" — but the image that resonates more than 60 years later of the golf champion, that came to define his pluck and precision, ran six by nine inches on the bottom of page 28, sharing a spread with photos of spectators hopping a stream on the ninth hole, the three playoff participants and a dog interrupting Johnny Bulla's shot.

"Anticipation is the key word in the coverage of all sports," Peskin later told biographer John Thorn for A Life in the Shadows: The Sports Photography of Hy Peskin. For his seminal shot of Hogan, Peskin had thought ahead about what the scene would be like on the 18th hole when the sun was low, the gallery was large and the championship was in the balance. "Hy Peskin didn't accidentally end up behind Ben Hogan," says Neil Leifer, whose superb sports photography from the 1960s and 1970s helped define the genre. "He obviously had a picture in mind. The great sports photographer plans, and then he executes. Peskin executed it perfectly."

Hogan, his weak, bandaged legs fading over the final nine holes of a double-round Saturday, had lost a three-stroke lead. He needed to par the 18th hole to make a playoff with George Fazio and Lloyd Mangrum, who had already finished at seven-over 287. Hogan drove up the left side of the fairway, his tee shot leaving him more than 200 yards to an elevated green. Peskin, who was 34, a few years younger than Hogan, hustled into position behind the star's ball, securing a place amid spectators that included some of Hogan's fellow pros who also wanted a glimpse of history.

It was no surprise that Peskin, who would become Sports Illustrated's first staff photographer, was in the right place at the right time. As Thorn wrote, "... what truly set Peskin apart from his peers was his combination of inventiveness and athleticism." Thorn quoted a 1961 Jim Murray column from the Los Angeles Times, in which Murray described Peskin this way: "He runs more laps than Vladimir Kuts and this is remarkable because Hy only stands about 5'7" and weighs about 195, most of it evenly distributed below the waist. Moreover, he ran his laps under full pack of two Leicas, one Rollei, sacks full of film, a telegraph from the editor, and a note from his wife telling him not to forget to pick up the roast..."

Hogan executed the shot he had to have — flighting a low 1-iron that landed just short of the putting surface and bounded safely onto the front of the green 40 feet from the flagstick from where he would two-putt for the essential par — and, as the golfer followed through, Peskin captured the moment in black-and-white. "I knew as I shot it," Peskin told Golf Digest in 1998, "I had something really terrific."

Peskin's picture is a classic, timeless composition with great depth of field owing to the small aperture he selected. Hogan, in light-colored flat cap, shirt, slacks and shoes, has turned fully toward his target, eyes you cannot see focused on the green. He is perfectly balanced on his left side, his right foot up on his toes, the famous extra spike on the sole (for better traction) clearly visible. His slacks are sharply creased, the bulk of the hidden bandages noticeable from thigh to knee. A small divot has been taken out of the smooth fairway grass, evidence of proper contact by an extraordinary ball-striker. The clubhead is blurred ever so slightly, connoting the motion of the strike. The ball, if you look closely enough, can be seen en route.

It is how Hogan is situated — how he fits in the landscape — that makes the image so striking. Peskin was only about 15 feet away from his subject, the distance of foul line to hoop on a basketball court, shooting with a "normal" lens that provides roughly the field of view of the human eye. That Peskin's image has neither the distortion of a wide angle nor the compression of a telephoto contributes to the feeling of "being there." (Beautifully executed, final-round, top-of-the-backswing pictures of Nicklaus at the 1978 British Open by Ruffin Beckwith and Michael O'Bryon at the 1986 Masters relied on the reach of long lenses.)

There is only one predominant shadow in the historic frame, Hogan's, knifing toward the spectators, half a dozen deep, lined up on the left. The fans are in close, and they are positioned in a straight line (no one encroaching more than anyone else, in seeming lockstep to the era's perceived orderliness) until just short of a yawning bunker well short of the green, where they arc in a semi-circle a fraction wide of Hogan's upright and taut left forearm. Another group of spectators curls around the other side of the bunker, in front of a huge tree that fills the upper-left corner of the frame, then up the slope toward the green and around it. On the right side, inside and beyond a large tree that anchors that portion of the picture, more spectators are packed in for a look. The flagstick isn't noticeable, but in the distance beyond the right-front greenside bunker, a flagpole looms just tall enough to stand out from the trees beyond.

"It is the perfect photo," says Vuich. "The way Hogan is framed in it is absolutely perfect. His left elbow at the finish is just inside the gallery on the left. His hands are just below the green and gallery at the top. The composition, it's all there." Within the eye-pleasing view there is even more photographic gold: Two triangles of visual interest are formed by Hogan's shadow, his left side and the strip of fans and by the angled clubshaft, the front of the green and the bank of spectators in the valley on the right. A pocket of empty grass catches the eye in the middle distance of the left approaching the large tree up the hill.

Indeed, nothing is lacking: It is an impeccable look at a champion making an unlikely, successful comeback, solidified when Hogan won the 18-hole playoff. Time has only varnished the iconic nature of Peskin's perfect photograph.

"I would like to think that what makes a picture iconic is when one takes a great picture of the moment of a memorable event," says Leifer, whose 1965 ringside photograph of Muhammad Ali towering over a just-knocked-out Sonny Liston is one of the all-time greatest sports pictures. "My Ali-Liston picture would have been just another nice knockout picture had it been the third preliminary with two fighters everyone has long forgotten. But it was the moment in a Muhammad Ali heavyweight championship fight. The Hogan picture is the moment."

Leifer, 70, was inspired toward his craft by Peskin's work. "Putting it as simply as I can, he's one of my heroes," Leifer says. "He's arguably as good a sports photographer as there has ever been. When I was a kid, I started looking at his pictures. It would be fair to say I wanted to grow up to be him as a photographer."

Peskin's signature image is not only the most memorable photograph in golf history but also one that transcends golf. It is in the realm of Nat Fein's picture of a dying Babe Ruth saying goodbye at Yankee Stadium, Leifer's image of a triumphant Ali, Iooss' shot of San Francisco 49er Dwight Clark snatching a touchdown pass, Heinz Kluetmeier's jubilant United States hockey team at the 1980 Winter Olympics.

Martin Axon, a platinum printmaker who re-introduced that printing process to his native England in 1979, is a master of his craft — a man who has printed exquisite, richly toned images for Robert Mapplethorpe, Annie Leibovitz, Patrick Demarchelier, William Klein and other legends of photography. Axon hasn't done much sports work in his acclaimed career, but he is a keen, lifelong golfer. In the late-1990s he decided to print a limited edition of Peskin's Hogan. By this time Peskin had long gotten out of photography to pursue philanthropic interests, changed his name to Brian Blaine Reynolds and was known for filing a lot of lawsuits.

New York Yankees vs Cleveland Indians double header

at Yankee Stadium on September 11, 1955.

Photo: Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Axon, who moved to New York City and now lives in Connecticut, made an arrangement and went to the Time-Life Building to copy the image so he could print it at his studio. Part of the legend of the Peskin shot has been that it was taken on four-by-five-inch sheet film in a Speed Graphic camera. When Axon got his hands on the holy grail of golf images, however, he saw it was a 2¼ inch-by-2¼ inch square negative. "It was definitely 2¼ square," Axon told me recently. "There is definitely more image above and below what is typically printed. There is too much grass in the foreground and too much sky." Like any photographer, though, Peskin had visualized what a rectangular presentation would look like. There could have been frame lines within a viewfinder so Peskin could pre-visualize what an image cropped to an oblong shape would look like.

Axon discovered the historic image attached in a small strip preceded by a shot of Hogan, his fellow competitor Cary Middlecoff and others walking off the 17th tee at Merion in the final round. Hogan and Middlecoff, are close together, seemingly in conversation, and Hogan's expression is a half-smile, perhaps the expression of relief of an aching athlete who can now see the end of a long day -- and the prospect of a cold drink and a hot bath — regardless of the outcome of the tournament.

How to explain the smaller than believed dimensions of the famous negative? Peskin could have equipped his Speed Graphic with an accessory roll-film back, which would have allowed him to shoot 12 exposures before changing film. Bystanders at the scene have recalled Peskin having a cumbersome camera, so this makes sense. It is also possible Peskin used a less bulky Rolleiflex, which he was also known to carry on assignments. Regardless of the instrument in Peskin's hands, neither camera had an automatic advance; he had only one click of the shutter to capture the moment.

Almost five decades after the frame was exposed, Axon was moved when he handled it. "When you hold someone's negative," he says, "You go, 'This was the actual moment.' When you're holding the film, it's different than holding a print because you know the film was there at that moment in time."

It is, Axon says, a perfect negative, which explains why it has been successfully printed in so many forms over the years. "It's just one of those pictures that has so much quality," Axon says. "I just darkened the sky a little bit, so you had a better chance of seeing the ball, and burned in [to darken] the characters on the left side, so the spotlight would be a bit more on Hogan. But they were very minimal adjustments. You could print it on a tablecloth and it would look fantastic."

Axon, who has spent thousands of hours in his darkroom printing images that were meticulously set up, was struck by the composition of Peskin's photojournalism. "The style is so wonderful, Hollywood looking," Axon says. "Even the fat guy standing in the gallery on the left is incredibly well dressed. Everybody is so close to him playing the shot. Hogan's posture is statuesque, and the angle of lighting on him shows every crease in his pants — the sun his shooting directly across him like theater lighting."

That Peskin's picture was bursting with the ingredients to make it one for the ages is all the more clear by examining a shot taken on the 18th hole of the three-man playoff by a photographer named Alex Bremner. Hogan hit a much longer tee shot than during the fourth round, and he didn't hug the left side. He is using a 5-iron. There is gallery left, right and ringing the green, but the spectators don't snake around the sand on the left. The right-greenside bunker guarding the green is blocked by Hogan's torso. Hogan is wearing a dark sweater instead of a light shirt, not standing out as he did in the Peskin shot. Instead of Hogan's single shadow creating interest, there is one behind him and several in front. Hogan's finish, because he wasn't trying to knock the ball down, is higher. Through no fault of Bremner's, it is a moment in a golf tournament, but it is not the moment. It documents a golfer finishing off an amazing achievement but has none of the dramatic tension of Peskin's image. It is a fast-food chain hamburger to a hand-formed burger lovingly grilled in the back yard.

Peskin, presumably, was the only photographer behind Hogan in the 18th fairway at Merion that sunny afternoon, or if someone else was, his film was never published. Therein lies a huge distinction between 1950 and today. If access could be gained to that spot, there would multiple photographers on hand. I executed a wonderful sequence of Mize holing his long chip shot and leaping skyward in exultation, but so did a number of other photographers.

Vuich has produced the most Peskin-like image of this era's Hogan, Tiger Woods, on the 72nd hole of the 2001 Masters, as Woods was completing the "Tiger Slam." From a photo tower about 60 feet behind the 18th tee at Augusta National, a position that no longer exists, Vuich captured Woods at the top of his backswing, an arresting combination of man and moment, much like Hogan at Merion in 1950. The image ran on the cover of the following week's Sports Illustrated.

As in the Peskin shot, the sun is low, cutting across the frame. Woods is driving through a chute of spectators on either side, with those behind the tee in the foreground. The green, and history, is in the distance. "There are some similarities," Vuich says. "The orderliness is there, but of course there is a rope line. When Tiger was on the 17th fairway it was overcast, but then God turned on the light switch, because the sun popped out."

Vuich shot with a medium format camera that produced a 2¼-inch inch image, as did Peskin. He used a Mamiya 7 with a 43 mm lens, a wider view than Peskin's normal lens. It is a different perspective than Peskin's shot, no less effective in artfully capturing a sports legend at the peak of his powers. "The shot of Fred's, only he got that," Leifer says. "You said, 'Wow.' I remember seeing it and being bowled over. I like Fred's picture as much as I like the Hogan picture. Clearly he was thinking of the Hogan picture. I wish I had taken Vuich's picture."

As long as Vuich, who is 57, photographs golf action, he knows he might not ever produce another picture as memorable as his Woods shot from 2001. "Just a week ago, a friend of mine asked me whether I had photographed Payne Stewart winning the U.S. Open at Pinehurst in 1999. He said, 'Did you shoot him at 18? Is it the famous photo?" Vuich says. "I told him there really isn't a famous photograph because everybody had the photo unless you had an equipment malfunction. The green was circled by photographers, and everybody had an angle. Well, if everybody had it, then it's kind of tougher to be famous."

Even Cannon, who has special access through the R&A for the British Open, doubts Peskin's image can be matched. "Technically I could do it now with the job I've got with the R&A," Cannon says. "They allow me out in the fairway with the TV cameras. So I have the most exclusive access in the Open. But the crowd would never encroach like it did in Hogan's day. You're never going to get a chance for a gallery to be that shape."

from USGA president James Standish.

Photo: AP Photo

There have been tens of thousands more photographs — a guess — taken of Tiger Woods than were taken of Ben Hogan. Vuich's from 2001 stands out, as a 21st century study of the best golfer of his time, but so does longtime Golf Digest photographer Szurlej's, a fantastic moment of Tiger enthusiastically reacting to his holed chip for birdie on the 16th hole in the final round of the 2005 Masters. Whereas Vuich's composition is retro — although it was taken at the top of the backswing with a quiet contemporary camera that afforded that luxury — Szurlej's is thoroughly modern.

Taken with a telephoto lens that could hardly have been imagined in 1950, from well away from the green, the picture shows Woods and caddie Steve Williams, exploding with joy after the unlikely shot went in the cup. It is framed perfectly with very out-of-focus spectators in the foreground and others beyond the golfer, creating the effect of a visual spotlight on the going-wild Woods. What Peskin's shot was metaphorically as regards Hogan's game of precision, proper golf of so many fairways and greens, Szurlej's picture superbly captures the raw dominance of Woods, whose celebratory fist pumps after he does something amazing have been a trademark over the last two decades. It was also a view, even in these more ubiquitous times, that no one else had. "I look at Steve's shot," says Cannon, "and go, 'My goodness.'"

There is a plaque on the 18th fairway of Merion's East Course, about the size that Peskin's photo ran in Life, marking the spot where Hogan hit his famous shot. Golfers practicing for this week's U.S. Open might pause there and conjure the scene of 63 years earlier. Thanks to Hy Peskin, though, they don't have to only imagine what it was like. Thanks to one of the best photographs ever taken, a decisive moment for the ages, they can see it and smell it.

"Well-wishers forming a solid wall outline Ben Hogan's approach on the last hole, indicating the great pressure he was under in the Open," Life wrote in its original caption. "But Ben seems to thrive on pressure..."

And, in a fortunate hundredth of a second confluence of great athlete and great photographer, so did Hy Peskin. As long as there are golf tournaments, neither of them, nor their grace and talent when it mattered, will be forgotten.