News

U.S. Open 2017: For a change at a U.S. Open, players won't be putting out of fear

ERIN, Wis. -- We know what putting looks like in the U.S. Open. Cautious, shading toward tentative. Tense, edging into tortured. Results eliciting unusually strong outward reactions reflecting either relief or devastation.

The standard U.S. Open 20-foot putt? A defensive lag finishing on the low side, leaving - if the ball doesn’t drift too far along a slope – a short up-hiller. Basic damage control.

It’s been this way for decades. Since the championship made a calculated move to be the hardest tournament in the world in the early 1950s, U.S. Open greens have almost always featured a more pronounced combination of speed and undulation than the other three majors. In the days when greens were generally reading about 8 on the Stimpmeter, U.S. Open green would read 10s. These days, greens at regular PGA Tour events run about 11, the PGA Championship about 12 and the Open Championship 10 at most. Last year, the surfaces at Oakmont were at least 14, and around 13 at Erin Hills.

Ross Kinnaird

Depending on the year, the Masters, which are estimated at 13 on the Stimpmeter, can offer the most diabolical greens. But a mitigating factor in the extreme challenge of the Alister Mackenzie complexes is the familiarity players gain from the tournament permanently played at Augusta National.

Regardless, anecdotal memory supports the case for more short misses occurring in the U.S. Open than anywhere else. A lot of them are the heartbreaking kind, when the difference between a par save and a soft bogey can change momentum or even break the will.

The buildup from such putts gives the U.S. Open its distinct pressure, one in which nerves are more savagely frayed. It’s no accident that the championship’s history of short misses that cost victory on the 72nd hole or the last hole of a playoff is more extensive than the other majors. Look up video of Sam Snead excruciating 30-inch miss against Lew Worsham in 1947. I vividly remember Bob Rosburg, one the game’s great all-time putters, leaving a three-footer short on the last hole at Champions in 1969 when he finished second by a stroke to Orville Moody. There is Davis Love III’s miss from the same length at Oakland Hills in 1996. And, of course, Retief Goosen’s stab from two feet at Southern Hills in 2001 that dropped him into a playoff (and moments before, Stewart Cink’s even shorter miss that kept him out of the playoff). The most recent such short-range disaster was Dustin Johnson’s pulled three-footer at Chambers Bay in 2015.

“There will be more putts made in this Open than we’ve seen in a long time,” Erin Hills co-architect Ron Whitten says.

Conversely, the U.S. Open has had very few heroic putts on the 72nd to win the championship by one. The most famous are Payne Stewart’s 15-footer for par to steal the 1999 Open at Pinehurst, and Tiger Woods’ do-or-die 12-foot birdie at Torrey Pines in 2008 that forced a playoff against Rocco Mediate.

Traditionally, the U.S. Open is much better at breaking hearts than lifting them.

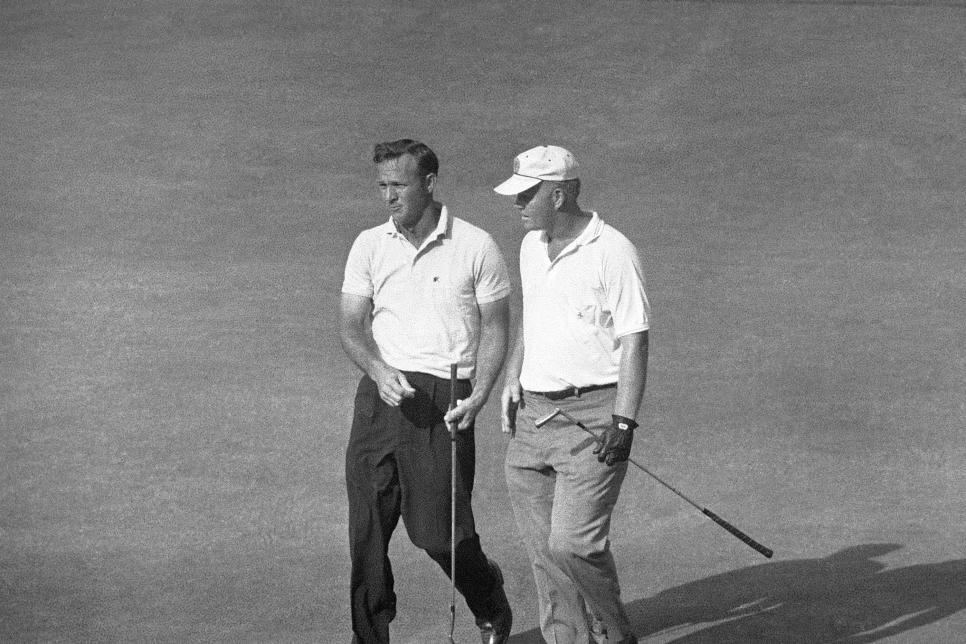

AP Photo

Jack Nicklaus was the ultimate U.S. Open putter. His formula was to keep hitting iron shots into the middle of greens and then take pains to avoid three putts by snuggling his approach putts to tap-in range. So that when Nicklaus had to make a crucial short putt, he had the mental energy and focus to beat down and will it in.

“My philosophy especially at the U.S. Open was always to try to leave it around the hole rather than charge the birdie,” Nicklaus says. “I developed that thinking in part from watching Arnold [Palmer], who always had a four-footer coming back, and the accumulation it put a lot of pressure on him.”

Nicklaus also pointed to precarious hole positions that dictated conservative putting. “A lot of times in the U.S. Opens, you found that they put the pins a little bit more on slopes, maybe because since the courses didn’t hold championship but every 10 years or so, they weren’t as aware of trouble spots as a course where they went every year. So you saw a lot of putts sort of slide away and keep going. They are trying to create the most difficult challenge they could, and they had the golf courses and greens to do it.”

This year, however, things might be different. For as tough as Erin Hills is, its greens might actually be gettable.

Erin Hills, built in this century, doesn’t have the kind of slopes that you see on a Golden Age course, which feature grades as steep as 5 percent, and were never intended to putted at 12 or higher on the Stimpmeter. Instead, the greens often feature multiple tiers. Very long putts between tiers will be challenging, but when the ball is on the same tier as the hole, offer a lot of fairly straight putts.

The architects decided that severe grades would have conspired against the public golfer, creating slow play and a frustrating experience. And the heavy winds that can hit the area would – in a U.S. Open - make heavily sloped greens not just unputtable, but unmarkable.

What the players will see this week are surfaces that USGA executive director Mike Davis says are the best conditioned he has ever seen, and which might be slowed and smoothed a touch by the rain thus far. Bottom line, the leaders are likely to assess the path to the hole with more confidence than fear.

“There will be more putts made in this Open than we’ve seen in a long time,” said Ron Whitten, the architectural editor for Golf Digest who partnered with Michael Hurdzan and Dana Fry on the original design of Erin Hills. “I think a lot of guys are going to sink a lot of 30-foot putts on these greens. I predict a lot of six-birdie, three-bogey kind of rounds.”

Theoretically at least, Erin Hills plays more to the putting geniuses than U.S. Opens normally do. The need to keep making safe pars plays against virtuoso displays. Billy Casper is considered to have won his two U.S. Opens with remarkable putting mastery, while the finest exhibition I’ve ever seen on classic U.S. Open greens was put on by the aforementioned Goosen at Shinnecock Hills in 2004. With the surfaces dried to a fine crustiness on Sunday, Goosen ran the table on the back nine when the rest of the field was struggling to two-putt.

But at Erin Hills, putters like Jordan Spieth, who when he is locked in considers a relatively straight 25-footer a serious scoring opportunity, will have an enhanced opportunity to take advantage of their special skill.

In his day in the 1970s and 1980s, Ken Brown was such a putter, good enough to earn the nickname “One Putt,” which also happens to be the title of his excellent instruction book on putting. Now known for his for his whimsically astute television commentary, Brown will be part of the broadcast team at Fox doing the telecast from Erin Hills.

Brown has studied the course, and concluded that good ball-striking that gets the ball on the proper tier will be rewarded. “Once on the flat areas, there should be plenty of putts holed,” he says.

Icon Sportswire

But beyond the physical characteristics of the greens, Brown also believes that today’s players have become collectively better at relentlessly holing out from short range. He points out that in recent years, the PGA Tour’s leader in putting from three feet and in has gone the entire season without missing from that distance.

“They are proving that it’s the one thing that might be perfectable about the game,” Brown says. “Whether it’s the purity and smoothness of today’s surfaces, or the techniques and the putter improving, they simply aren’t as afraid of the comebacker. It leads to more determined runs at their birdies. Which might lead to the odd three putts, but it also leads to a lot more birdies from distance than we made.”

And it’s the sight of those kinds of putts going in that might end up being our distinguishing memory of the first U.S. Open at Erin Hills.