“My game is vulnerable.” It’s the adjective that Tiger Woods has so mightily resisted using over the last three embattled years. Not vulnerable physically or vulnerable mechanically, the two areas Woods has preferred people think were the causes of his poor play. Vulnerable mentally.

Reading the word—which was accompanied by the phrase “after a lot of soul searching”—in Woods’ statement on Monday announcing his withdrawal from this week’s Safeway Open (as well as the Turkish Airlines Open in three weeks) caused a collective exhale. Finally, Woods was no longer hiding behind a bulletproof pose. So badly has “vulnerable” been missed, a single reference immediately confirmed that the psyche has been the heart of the issue all along.

There’s now more empathy for how hard it is to be Tiger Woods. But the uncharacteristic candor also brought a sense of relief, a sense that a burden had been eased and there is a way forward.

Woods didn’t specifically say how he was vulnerable, but even as his surrogates talked in generalities, the mind of close observers went to the phenomenon of chip yips.

For years now, Woods has been stuck in a trap of the presumed perfectionist seeking perfection, while internally lost at sea. He’s been hiding in plain sight, and finally he can hide no more. Putting his vulnerability out there might be a turning point.

It remains jarring and even surreal to watch a compilation video of Woods seemingly helpless around the greens in December 2014 at his Hero World Challenge, and then at Phoenix and Torrey Pines. And though he somehow overcame a recurrence at the 2015 Masters, the problem resurfaced on the final nine at his last official tournament appearance, the Wyndham Championship in August 2015.

Woods’ chipping woes remain a lingering, and possibly permanent problem. It’s not overstatement to call them a potential career ender. Besides all the strokes lost, for a touring pro there is the traumatic humiliation of such a proportionally big miss in such a little space, either from a chunk that travels only a fraction of the intended distance, or a blade that doubles it (or worse). Woods’ most recent short-game stats speak for themselves. But what’s more telling are off-the record eyewitness accounts from his practice sessions in Florida that the problem persists.

Of course, the chip yips could be a sub-manifestation (along with first-tee jitters) of a larger issue, one that many all-world performers have fallen prey to: stage fright. Indeed, the greater the fame and the attendant expectations and obligations, the harder it can hit.

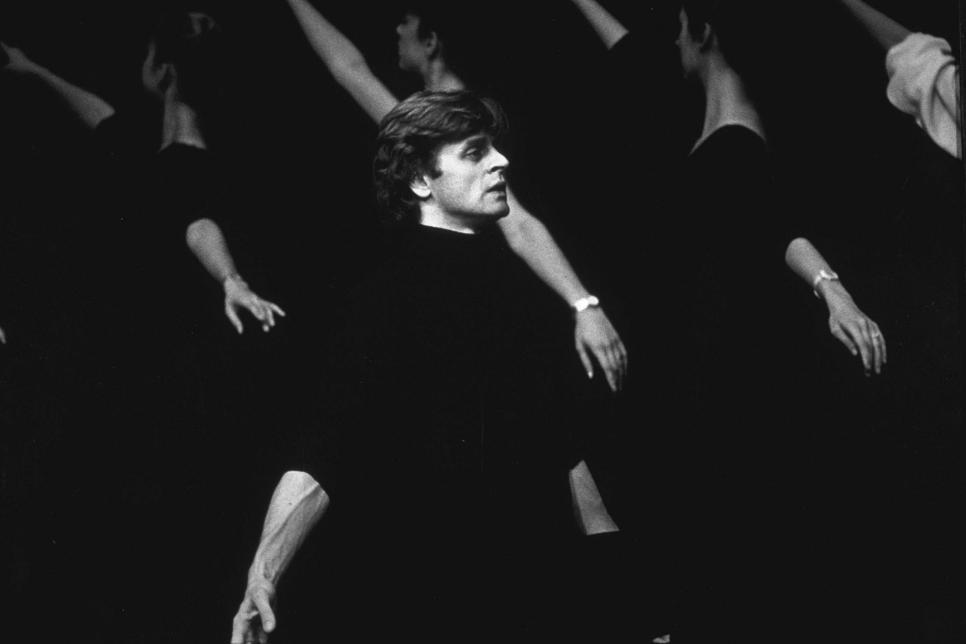

In the constantly judged world of entertainment, it’s the very best at their craft in the latter stages of their career who often are the most susceptible to paralyzing bouts of stage fright. Laurence Olivier, Maria Callas, Vladimir Horowitz, Barbra Streisand and Mikael Baryshnikov are a few of the more notable cases.

Baryshnikov, by acclimation the greatest ballet dancer in the world in the 1970s and 1980s, explained that his ordeal only got worse with time. “I am onstage more than 50 years,” he said in a recent New Yorker article. “Sometimes I do shows every night for weeks. Still, it never doesn’t come. Starts four hours before. I don’t even try to fight it anymore. I know it will always be there.”

Ray Fisher

Of course, few in the arts or sports can escape some degree of performance anxiety. Part of being professional is controlling nerves so that execution doesn’t suffer, or better yet, using the adrenalin to achieve greater heights. The late martial-artist master and actor Bruce Lee wrote, “The experienced athlete recognizes [the presence of stage fright] not as an inner weakness, but as an inner surplus.” Perhaps the most prodigious winner in any team sport, Bill Russell of the Boston Celtics, threw up before every game.

In golf, Bobby Jones would regularly lose more than a dozen pounds from the strain of a week of tournament golf. Ben Hogan and Mickey Wright went through tortures putting their game on display late career. It was always impressive to observe the zone of quiet intensity that Arnold Palmer or Jack Nicklaus would enter before a late-career competition or even exhibition. For the great, the burden of constant judgment is part of the deal.

The irony of Woods’ current plight is that arguably no player in history had been better at rising to the biggest moments. In a Golf Digest article about him at the age of 14, Woods described the pressure of winning as “a lion tearing at your heart,” but also believably professed to love it.

But nothing is forever, and the combination of all the energy required, physical erosion and the immeasurable effect of a major public humiliation caused Woods to hit a tipping point and go the other way. The Safeway Open host, Johnny Miller, identified with Woods’ plight and spoke movingly about what he went through in 1977, when he suddenly fell from the very top of the game to near the bottom. For the next several years, posting a score in tournament golf became an exercise in doubt and dread. “There’s so much pressure when you can’t deliver like you used to,” he said.

Of course, players, swing coaches and even many sport psychologists adamantly hold that publicly admitting weakness should be avoided. Many shook their heads when Rory McIlroy was recently open about his putting woes. But it’s instructive that ever since opening up, McIlroy has putted better.

For years now, Woods has been stuck in a trap of the presumed perfectionist seeking perfection, while internally lost at sea. He’s been hiding in plain sight, and finally he can hide no more. Putting his vulnerability out there might be a turning point.

The good that comes from dropping defenses and embracing vulnerability is the main premise of author Brene Brown, whose talk on “the power of vulnerability” at the 2010 TEDx Houston conference has been viewed on the internet more than 6 million times. It’s hard to miss how Brown’s wisdom, can be applied to Woods.

“Perfectionism is the belief that if we do things perfectly and look perfect, we can minimize or avoid the pain of blame, judgment and shame,” Brown said in a recent article in Fortune magazine. “Perfectionism is a 20-ton shield that we lug around, thinking it will protect us, when in fact it’s the thing that’s really preventing us from being seen.”

Or this, from Brown’s book, Daring Greatly: How the Courage to be Vulnerable Transforms the Way we Live, Love, Parent and Lead: “Vulnerability is not weakness, and the uncertainty, risk and emotional exposure we face every day are not optional. Our only choice is a question of engagement. Our willingness to own and engage with our vulnerability determines the depth of our courage and the clarity of our purpose; the level to which we protect ourselves from being vulnerable is a measure of our fear and disconnection.”

“Fear and disconnection” is an apt description of the territory in which Woods has spent too much time. Refusing to admit weakness made him weaker. Now that he has made a first step in that direction with just one word—vulnerable—he has got a better chance get stronger.