News

Tiger, 10 Years Later

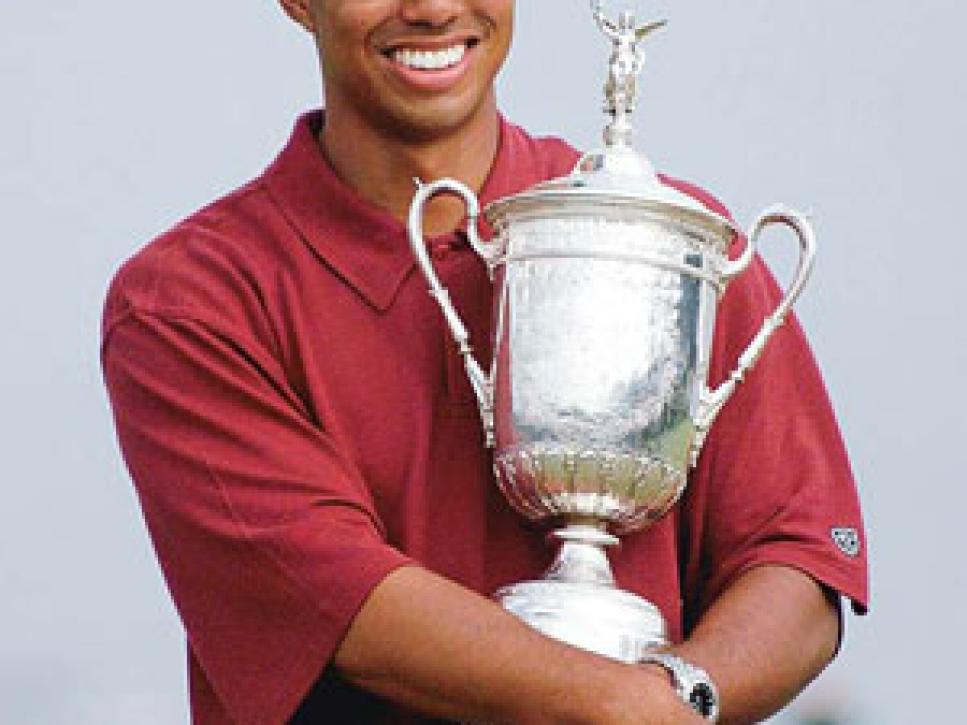

Tiger Woods might disagree, but his performance a decade ago at the U.S. Open at Pebble Beach stands as the greatest golf ever played. Though the objective evidence seems irrefutable -- 72 holes in a championship-record 12 under par and a 15-stroke margin of victory that is the record for any major championship -- it's the subjective impressions that best make the case. Woods demonstrated as he never had before and to a degree he hasn't since that he could hit shots his opponents simply couldn't. His aggregate of power, finesse, control and competitive ferocity on a course more testing than the Augusta National over which he had won by 12 at the 1997 Masters gave him a wider advantage in raw weaponry over a championship held than any ever held by Jones, Hogan or Nicklaus.

When Woods sliced through heavy rough with a 7-iron on Pebble Beach's par-5 sixth hole with enough force and precision to send his second shot 210 yards over the edge of Stillwater Cove and onto the green during Friday's round, Roger Maltbie's early but accurate call -- "It's not a fair fight" -- perfectly captured the palpable sense that the proceedings would be more coronation than competition.

Ever since, the 2000 U.S. Open has been the prism through which we have evaluated Woods. The greater his feats -- and he has won 11 majors since -- the more they are compared to Pebble Beach. The question that won't go away is whether he has really continued to improve -- as he has always insisted -- or if the golf he played at 24 will ultimately be considered his historical peak. Will the changes in Woods as a player post-Pebble -- all carefully wrought and hard-earned -- be judged as substantive gains or intrusions on a rare state of athletic grace?

As Woods returns to Pebble Beach 10 years later, the issues have become more intriguing. Even Woods cannot yet fully know how his public scandal and the 45 days of in-patient therapy he underwent to address deep-seated problems have altered him as a player and as a person.

At the Masters, his first tournament after a five-month absence from competition, Woods showed skill and grit but lacked the sharpness necessary to win. His tie for fourth place was a strong effort, but a more accurate reading of where he is and where he's headed will come in June at Pebble Beach.

'THE ROLL OF ROLLS'

Woods was never more ready to play than at the 2000 U.S. Open, but the perfect moment in time really began in early May 1999. He was on the range at Las Colinas at the Byron Nelson when he called Butch Harmon at his teaching school in Las Vegas and said simply, "I got it."

From the time Woods won the '97 Masters, he had been working hard to change what he considered a longtime swing flaw: a too-inside takeaway that shut the clubface and caused the shaft to cross the line at the top. Woods believed the move was inhibiting his distance control and shotmaking versatility, so he committed to an uncompromised fix.

The sacrifce was high: He won only one event in 1998 and one other at the beginning of 1999. Even after shooting a 61 at the Nelson after his call to Harmon, Woods faded to a tie for seventh. But he won his next outing, the Memorial, beginning a torrent of 16 victories in 27 tournaments. With a never-before-seen combination of length, touch, consistency and competitive drive, Woods began to change the perception of what was possible in modern professional golf. As Harmon put it, "Tiger got on the roll of rolls."

Before leaving for Pebble Beach, Woods spent time tuning up with Harmon in Las Vegas. On his last day there, playing with then-amateur Adam Scott, Woods shot a course-record 64 through high winds on a Rio Secco course set up fast and firm to simulate major-championship conditions. "I had never seen golf played like that, and it almost stopped me from turning pro," Scott says. "After a while, I realized that the only person who could play like that was Tiger."

Woods arrived at the Open on Sunday night, staying in a villa behind the 18th green. Immersed in his preparation, he declined joining some 20 other players in a Wednesday-morning memorial service for Payne Stewart along the shoreline of the 18th fairway. "I felt going to the ceremony would be more of a deterrent for me, because I don't want to be thinking about it," he said at the time.

Woods was criticized, but Harmon saw an athlete ready for a peak performance. "Tiger was very relaxed and calm, and he had so much confidence in the way he was hitting the ball," Harmon says. "It had taken awhile, but he had gotten into a comfortable slot, feeling like he was taking the club a little outside and up. He was free of mechanical thoughts, and he had this pure aggression. At the same time, his distance control with his short irons was the best it had ever been."

Indeed, the Woods of 2000 is spectacular in video retrospectives. His leaner body moved with more speed, and though he employed a shorter backswing with less wrist cock than he has in recent years, his sweep through the ball seemed wider and more majestic.

It produced the longest and straightest driving of Woods' career. In 2000 he narrowly trailed only John Daly in driving distance with an average of 298 yards (which was nearly 10 yards better than the next-longest) and hit a career-best 71.2 percent of fairways to rank 54th on the tour. And the Open that year was probably the best driving week of his career. His average of 299.3 yards was the longest in the field by more than six yards, and he ranked 14th in driving accuracy. With shorter approach shots than any other player, and the majority of them from the fairway, Woods led the field in greens in regulation (51) and makable birdie putts.

"People had been saying that Tiger couldn't win the U.S. Open because he didn't drive the ball straight enough," Harmon remembers. "At Pebble the first test of the driver is the second hole, which they were playing as a par 4 instead of a par 5, about 480 but narrow as a bowling alley. He got up on that hole on Thursday and carried it 300 yards absolutely dead straight. He did that all four days, like he was making a statement. He absolutely drove the ball magnificently."

But to caddie Steve Williams, who was in his second season with Woods, the key weapon was the putter: Woods had no three-putts for the week. He one-putted 34 times and took only 110 putts, sixth-best in the field.

"After a couple of practice rounds, we both agreed that the greens were going to be the deciding factor, because they were very quick, very firm and quite bumpy," Williams says. "It was going to be very difficult to lag the ball close, or chip it stone dead. We knew we were going to have to make a lot of putts in the six- to 12-foot range. So that was our emphasis."

Woods wasn't happy with his stroke after his practice round on Wednesday and went to the putting green for what became a 2½-hour session that lasted well into darkness. "The ball wasn't turning over the way I'd like to see it roll," he explained. It led to an adjustment in his posture, and his release was fixed.

"The only light was from the little shops beside the green, and we ended up being the only ones there," Williams says. "But on Wednesday before a major championship, before you go to bed you want to know in your mind that you've got it, that you're not going to go out Thursday searching. And he found a little key, and he left the green in a really good frame of mind. As it turned out, he putted incredibly. Perfect rhythm in his stroke, perfect contact, perfect speed. The balls just went in the center. And that was the difference."

Woods hit only one bad putt in the entire championship, a 10-footer for a double bogey that he left short and low on the third hole of his third round, when he was momentarily flustered after taking three hacks from deep greenside rough. He made his share of bombs, but the genius of Pebble was how he kept his rounds knitted together with timely short and mid-range putting. "It seemed like any time he made a small mistake, he'd make a great chip or hole a tough eight-footer," says Jim Furyk, who played with Woods in the first two rounds. "He got everything out of his rounds."

Woods' virtuosity with the two most important clubs was overwhelming. As Nick Price put it, "We all felt for the longest time that somebody was going to come along who could drive the ball 300 yards and putt like Ben Crenshaw. Well, this guy drives the ball better than anyone I've ever seen, and he putts better than Crenshaw. He's a phenomenon."

In Woods' estimation, the performance was most due to an ideal mind-set, one he alluded to at this year's Masters: "I think how I was earlier in my career -- I was at peace." When he hit his only bad drive of the Open, a hook into the ocean at the end of his second round, he exploded with profanity that drew a startled "Oh!" from Johnny Miller and plenty of scolding. But he recovered to hit a huge, straight drive followed by an ocean-challenging 3-wood from 260 onto the green for a two-putt bogey. Woods also retained his poise after his triple bogey, smiling and making birdies on three of the next six holes to return his lead to six strokes.

"There comes a point in time where you feel tranquil, when you feel calm -- you feel at ease with yourself," Woods said at the time. "I felt at ease; things just flowed. No matter what you do, good or bad, it really doesn't get to you. Even days when you wake up on the wrong side of the bed, for some reason, it doesn't feel too bad -- it's just all right. To have those weeks just happen to coincide with major championships is even better."

Woods possessed the effortless focus that perhaps only youthful genius allows. It was most evident on Sunday, with his lead growing into double digits, when he was determined not to make a bogey. When he holed yet another 15-footer, for par on the 70th hole, his reaction was the same as if he had just tied for the lead. "That was for me," said Woods, in a pure expression of a singular athlete seeking excellence.

There are obvious reasons Woods resists the idea that Pebble was his best golf. It intrudes on his mantra of constant improvement, particularly as he enters his mid-30s, traditionally considered a golfer's prime years.

But Woods' counter-argument can't be dismissed as sheer ego. In essence, he contends that the immense margin of victory occurred in large part because he had less game than he has now.

"Those weeks at Pebble and at St. Andrews [an eight-stroke victory in the British Open], yeah, I got hot," he said in a phone interview last October. "The reason I was able to shoot those rounds and win by large margins was because I played more aggressively. But the thing is, I had to. I didn't have as many ways of hitting the right shot, so sometimes I would force it against the percentages. If I was on, great. If I wasn't, I wouldn't really contend. I'm a much better iron player now than I was then. Also, I just didn't feel very good with the lag putting at the time, so I felt like I had to be more aggressive going at the flags. Now that my lag putting is so much better, I know if I can get the ball in the center of the green, I can basically two-putt from anywhere. Yeah, there are days when I'm hot when I'll take on a lot of flags. But there's nothing wrong with two-putting from 40 or 50 feet away. It takes a lot of strain off your game."

Adds Steve Williams: "Tiger has a greater understanding of his golf swing. It allows him to hit every shot, and more important, to make the right mechanical adjustment in the middle of the round, which is huge for his confidence. He knows that even when he plays very poorly at a major, he'll stay around par, which almost always leaves him with a chance to win."

Just as he had after winning his first Masters, Woods reassessed and re-engineered after winning his first U.S. Open. Deciding he wanted more ball control and shotmaking variety, in 2002 he began to move away from Harmon's teachings and more toward the ideas of his friend Mark O'Meara's longtime instructor, Hank Haney. Like Hogan and Nicklaus, Woods had calculated that the highest virtue in championship golf is not domination -- which even in the greatest careers occurs in short and usually unpredictable bursts -- but consistency, which can be long-term and reliable.

To that end, Woods eventually traded his game for one not quite as spectacular but which allowed him to better -- in the words of Nicklaus -- "play badly well." By having the skills to play the correct percentage shot, not just the aggressive shot, he would minimize mistakes over 72 holes and be in contention more often. And though dominating performances are revered in history, Woods decided he would be better served by winning more often, even if it would likely be by fewer strokes.

"I've learned you don't win golf tournaments on tour by just making a boatload of birdies," Woods said. "It's about minimizing your mistakes, about making your bad shots better. It always has been. I've always tried to play that way, but one of the reasons that I couldn't was that I wasn't as skilled as I am now at getting around the golf course."

In short, Woods went from seeking the "no limits" virtuosity that made him golf's greatest cross-over figure to simply "getting the W."

"It's surely not as romantic," Geoff Ogilvy, an admirer and student of Woods' golf, said before the Masters. "I played with him a few times in that period, and it was just stunning ball-striking. He hit the ball full out, and it flew very straight -- down the fairway, at the pin, with probably not much thought to the safe side, and taking on tight fairways with hard drivers. His game has changed a lot since then. He's become the master of doing what he needs to do to win the golf tournament. I think by now every player on tour is aware that the biggest reason Tiger is the best is because he putts the best. His play around the greens from 100 yards and in is at the same level. It's almost like he toys with everybody with his long game, because he can short-game himself out of bad ball-striking."

In 2009, Woods was first in scrambling (as he was in 2008), and a career-best third in sand saves. He ranked first in making putts inside 10 feet and from four to eight feet. And his winning percentage has gone up from the Tiger Slam years, when Pebble was part of his streak of taking the U.S. Open, British Open, PGA and Masters. From 1999 through 2002, Woods won 27 of the 78 official PGA Tour events that he played. From 2005-'09, he won 31 of 75.

But a key point: The numbers also indicate that Woods' later style might not be the best way for him to win majors. From 1999 through 2002, Woods won seven of 16 major championships. From 2005 through this year's Masters, he won six of 19. More tellingly, until the 2002 PGA, Woods never had a runner-up finish in a major. In the last five years, he has had five. It's notable because in majors Nicklaus finished second 19 times and third nine times. Recent results suggest that Woods, who has six seconds and three thirds in majors, will be more susceptible to close finishes and the kind of heartbreakers he avoided in the first part of his career.

Even for Woods, minimizing the worst rather than maximizing the best makes multiple-stroke victories in majors far less likely. It was his willingness to try riskier "talent" shots like his 7-iron at Pebble that helped him create separation from the field. The more conservative style of play might get Woods into contention more consistently, but because it's likely to produce fewer birdies, it will also restrict his chances for convincing blowout victories. Less likely to beat himself, he's more likely to get beaten by a talented long hitter playing an attacking game who has a hot week with the driver and putter -- in other words, someone playing the way he used to.

On the other hand, Woods is adapting to the fact that his distance advantage is almost surely gone. In 2009, his driving-distance average of 298.4 dropped him to 21st on the tour, his lowest rank for a full year. Although his driving accuracy improved to 86th and his total driving to 12th -- his best placing in those categories since 2000 -- there are now several other players more able to muscle a golf course than Woods.

The most notable statistic from 2009 was his average driver clubhead speed of 119.17 miles per hour. It was nearly 5 mph slower than his average in 2008 and nearly 4 mph slower than in 2007.

Woods conceded that after coming back from eight months of rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction surgery in his left knee in June 2008, "I hit the ball very short." But though he originally pointed to slow-healing "fast-twitch muscle response" as the problem, at the Masters he disclosed for the first time the loss of power was probably more due to an injury to his right Achilles tendon that occurred while running in early December 2008.

A physically healthier Woods might regain some clubhead speed. However, as he has grown older, he is more about control than power. He uses a softer and higher-spinning ball than almost any other player, and a shorter-than-average 44-inch shaft in his driver. Most observers agree that his swing changes under Haney have been more beneficial to his iron play than his driving.

"Even great players tend to be better with either the driver or the irons, because it's almost two different swings," says noted instructor David Leadbetter. "With Tiger, he's gotten more on top of the ball at impact than he used to be, a little more of a descending blow, and that's an action better suited to irons."

Though Woods is convinced his work with Haney has produced a net gain, there is no denying his game rouses less shock and awe. When Woods lost to Y.E. Yang at the 2009 PGA, failing for the first time in 15 tries to maintain a 54-hole lead in a major championship, other players began to say publicly what they had been whispering privately. "We stopped being intimidated by him," said Hunter Mahan. "No one is afraid of him."

Those sentiments have gained momentum since the scandal that has engulfed Woods since last Nov. 27. The aura of Woods' perceived superiority in mental strength was diminished by the colossal mistakes in judgment in his private life.

The fallout has also changed the question about Woods passing Nicklaus' record of 18 career pro major victories from "when" to "if." Even though Woods, who played his 51st major as a pro at the 2010 Masters, could go majorless for the next three years and not be behind Nicklaus' pace, the five more majors he needs now seem like a lot. Only 18 players in the game's history have won five or more; Byron Nelson and Seve Ballesteros each won only five. And before Mickelson won the Masters, no one else in the Woods era had more than three, a fact that Nicklaus picked up on earlier this year.

"So he has almost two lifetime careers to break my record," Nicklaus said. Previously, he had added to the urgency of the chase by citing Woods' past success at this year's major sites: "If Tiger is going to pass my record," Nicklaus said, "I think this is a big year for him."

So the pressure on Woods will be particularly intense at Pebble Beach: because of all that he has undergone since last November, because of what he did in 2000, and because the Nicklaus record keeps ticking louder. The tranquil state of mind that was Woods' key to peak performance -- a happy accident a decade ago -- will be actively sought. He has undoubtedly earned some wisdom through therapy, and he professes a renewed commitment to the Buddhist practices of his youth, of which he said at the Masters, "I just lost that, and unfortunately lost my life in the process."

Pebble Beach will offer a giant step in Woods' ongoing struggle for renewal. He might never again be quite the golfer who can win a U.S. Open by 15 strokes, but this year, another victory -- by any margin -- would be epic as well.

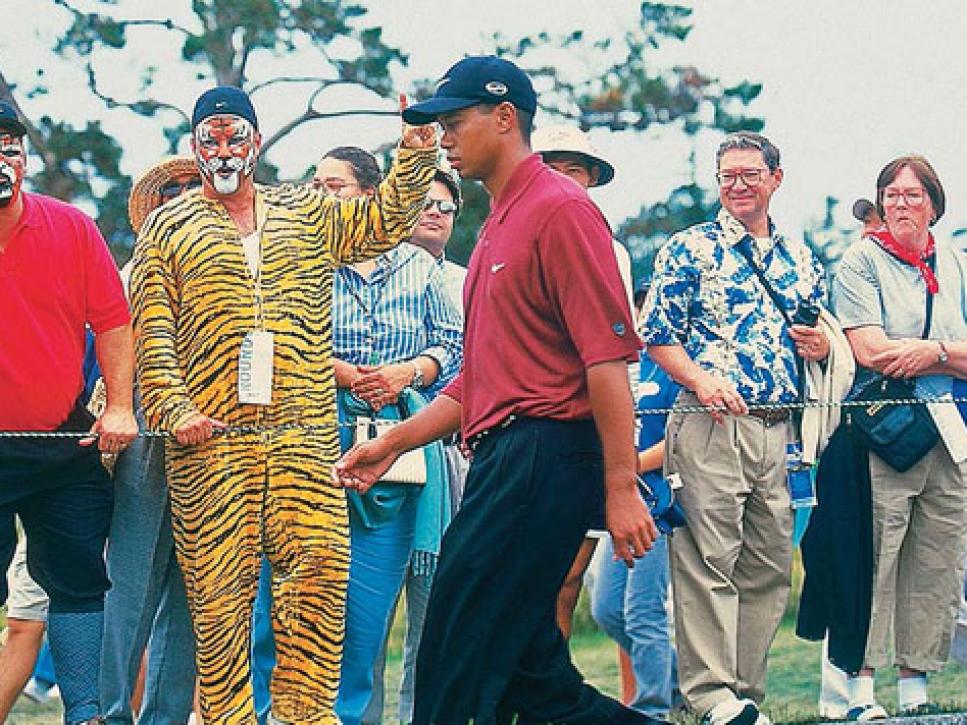

__2000: Woods remained focused at Pebble as the fans reveled (Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images). __