Tida In Thailand

Tida Woods, a native of Thailand, at the Grand Palace in Bangkok.

WEB EXTRA: Watch a slideshow of Tida's trip to Thailand narrated by Senior Staff Photographer Dom Furore.

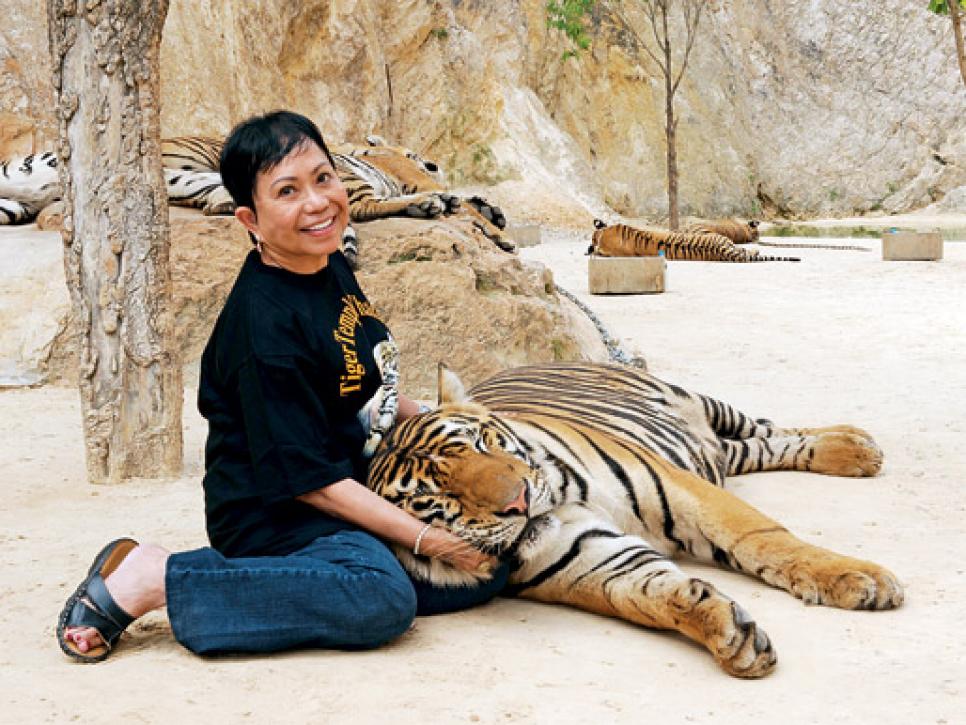

Too obvious. In Hollywood-speak, too on the nose: Tiger Woods' mother cuddling a live tiger.

Except this wasn't some cub. This was a 550-pound adult male tiger at Thailand's Tiger Temple, out on an alarmingly exposed area at the bottom of a rocky canyon with only a frail Buddhist monk in a flimsy orange robe holding a stick as her guardian. By most accounts, the monastery does an admirable job of "imprinting" tigers to be comfortable with human contact, and thousands from around the world visit every year without reported incidents. This tiger, along with about a dozen others within a 50-foot radius monitored by other monks, was deep into his mid-afternoon nap. Still, the words "Siegfried & Roy" kept coming to mind.

But Kultida Woods' bearing as she approached the tiger reminded me of my main impression the first time I ever saw her son, then 14, address a golf ball: utter poise, and an inner smile. Without hesitation, she sidled up to the beast, kneeled down and stroked its back. After a few moments, she shifted herself toward his face with what Cesar Millan of "Dog Whisperer" fame would call "good energy." Lowering into a sitting position, she scooted forward and, yes, lifted the tiger's head into her lap. And as time stopped for her traveling companions, she happily kept it there for more than a minute.

"Tida" is an animal lover who indulges four big dogs at her home in Southern California, and as a native Thai, the tiger holds an exalted station with her.

At the tiger temple run by Buddhist monks.

"I wasn't worried. I knew he trusted me," she says, adding, "Oh, his coat was so soft, and his head was so heavy." But noticing that her observers still seemed stunned, she decided to snap them out of it. "Hey!" she said. "Like mother, like son, honey," her throaty laugh celebrating the association she lives for.

Such was the verve Tida, 64, displayed during a week-long tour during the most recent visit to her home country. She moved easily from philanthropist to guide to entertainer, always remaining the trail boss. She has gone back more than a dozen times since first leaving for America in 1968. Though she says, "I live in U.S. 40 years now, in Thailand for only 25. In that way, I'm more American than Thai," Thailand is still her original home and the place she feels most totally herself. The stoic figure behind dark glasses and under a big visor that she has presented to the world while following her son on the golf course might have revealed few similarities with her offspring beyond their broad smiles, but in Thailand it's easier to see the Tida in Tiger.

It was a trip in which communal interaction came easily. Long journeys in a well-appointed hired van and shared meals led to a lively exchange of impressions and observations on the fascinating mix of old and new, order and chaos, that is Thai culture. The group stayed at a modern hotel on the periphery of Bangkok, and after breakfasts featuring exotic Thai fruits and juices, each day trip began with an excruciatingly slow crawl through what is widely regarded as the worst urban traffic in the world.

"Amazing Thailand!" our driver (nicknamed "Bad Boy" by Tida for his all-black outfits and mischievous expression) would sing out while waiting half an hour to cross an intersection impossibly jammed with all manner of vehicles, bicycles and animal-drawn carts, drawing laughter with a sarcastic play on one of the country's tourism slogans. Similarly, expatriates have an all-purpose acronym -- "T.I.T." ("This Is Thailand") -- for all the curveballs the culture throws out.

"In Thailand, you make joke, or go crazy," explains Pong Punsawad, Tida's 49-year-old nephew, who took a week off from his two small businesses -- a cleaning service and wholesale jewelry -- to ride shotgun the entire trip, tirelessly taking care of all group logistics and keeping his aunt supplied with her favorite green-tea drink and Thai throat lozenges.

Amid the teeming streets of Bangkok, struggle seems a given. But the various vendors, laborers and messengers, all making a small fraction of the average salary in the United States, collectively carry themselves with a buoyancy that has earned the country the nickname Land of Smiles.

Thailand has more than its share of problems, including chronic political corruption and regional rebellions, but Tida is proud of her people.

"Thais accept everybody, every religion, every custom," she says. "Doesn't matter if you are Buddhist or Catholic or Chinese, whatever, we celebrate every damn holiday." And when she adds, in a more serious tone, "There's no color in Thailand, not like U.S.," she's alluding to the rock that came through her kitchen window in 1974, a few days after she and Earl Woods moved into a previously all-white neighborhood in Cypress, Calif.

Thais are also known for their toughness, a reputation earned by an ancestral history of defending against invaders -- Thailand is the only country in southeast Asia never to be colonized by a European country -- and by the national sport of kickboxing, in which the fighters are trained to expend incredible energy while impassively absorbing pain.

"Yeah," says Tida, barely 5 feet, winking. "Asian is small but dangerous, honey."

At each stop, Tida invariably dispenses some homespun philosophy. At Bangkok's impossibly ornate Grand Palace in the central city, she makes a prayer offering to the statue of the Hermit Doctor.

"I ask him to cure my cough," she says, referring to a worsening nasal and throat condition that can trigger long and often exhausting coughing. "Hey, you got to believe in something, honey. I have strong belief in Buddhism. Like Tiger believing it will go into the hole, and then it does."

At the National Museum a few blocks away, she muses on her country's history, particularly her favorite of Thailand's nine kings, Rama V, who is often compared to Lincoln because he did much to end the society's dependence on indentured servitude.

"I enjoy the things that are old more than the new," she says. "You know, the test of time. In Thailand, you always respect the elders and history, which is what I taught my son. I know he liked Byron Nelson very much; he was my favorite of all the golfers I meet. Just the way he looked at me and shook my hand. I hardly talk to him. But I like him."

After a spirited spin through one of Bangkok's downtown malls, where Tida indulges her love of a bargain while haggling with the kind of shrewdness that makes her a formidable member on the board of her son's ETW Corporation, we head to an animal park known for its genial elephants. The elephant is the most revered animal in Thailand, and Tida has urged her son to donate to elephant-protection organizations. Just like the Tiger Temple, the access to the elephants is unencumbered in a way that liability laws would make impossible in the United States, but with the handlers at their sides, pachyderms are indeed friendly bordering on affectionate with humans, especially those carrying bunches of bananas.

Later, the handlers mount the elephants and direct them in a delightful game of soccer in a spacious arena, and they offer members of the audience a chance to ride. Without saying anything, Tida leaves her seat, and a few minutes later she is regally seated on an ornate saddle atop a majestic animal as it circles the arena. Watching, Pong smiles and shakes his head at his aunt's natural charisma.

"She's a star, too," he says. By way of explanation for her impulsive act, Tida says, "Hey, when you get a chance, you got to have fun in life."

A LONELY CHILDHOOD

Tida's purpose in inviting visitors was to bring attention to two schools -- the Buddhist Girls Convent School, for orphaned and abused girls, and the Ratchaburi Home for Mentally Disabled Children -- that she has chosen to receive funds provided by Tiger for supplies, added staff and expanded facilities.

"I tell my son that I want to help my country," she says. "He say, 'Mom, Thailand is your department. Go ahead and take care of business.' Tiger is generous, and I choose these two schools as the first ones because they are special to me."

Geographically, the two schools are close to where Kultida Punsawad was born in 1944, in the province of Kanchanaburi about 75 miles northwest of Bangkok, near the then just-completed and later to be immortalized bridge on the River Kwai. Emotionally, the convent school in particular strikes a personal chord. The youngest of four children of an architect and a teacher who divorced when she was 5, Tida was sent to boarding school until the age of 10, after which she was shuttled between her father's and mother's second families in what she candidly calls a lonely childhood.

"I always had to make my own thing," she says.

Such a mind-set was evident when, while working as a civilian secretary in the U.S. Army office in Bangkok, she met officer Earl Woods. After a few months, though she had never been out of her homeland and spoke only the barest English, she married him and left to live in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Tida's only child was born in 1975 after the couple had moved to California, and she made an extra effort to expose him to her heritage. When Tiger was a preschooler, Tida's mother, Chardcharvee, lived in the Cypress house for two years. When Tiger was 9, he took his first trip to Thailand, seeing the historic sites in Bangkok and meeting his maternal grandfather, Vit, whom Tida describes as "built like my son, tall and slim." He gave the boy a mother-of-pearl Buddha statue that Tiger still keeps in his bedroom.

Whenever Woods has competed in Thailand, he has given the impression of being on a mission, winning all three tournaments he has played there as a professional.

In 1997, on a trip in which Tiger was besieged by media from the moment his plane landed, he won the Asian Honda Classic by 10 shots. The next year, at the Johnnie Walker Classic, he shot 65 in the final round to make up eight shots on Ernie Els before defeating him in sudden death with a long putt that triggered perhaps the most intense fist pump of his career. In 2000, he won the same tournament by three shots.

At his mother's request, Tiger annually visits a Buddhist monk in Southern California, who he says has helped him live with more tranquility. And though it has angered some in the African-American community, Woods has always described himself as half Thai. "You see," says Tida, "Tiger will not disrespect his mother's heritage."

But more than nationality, what mother and son most share is temperament.

"I am a loner, and so is Tiger," she says. "We don't waste time with people we don't like. I don't have many close friends. Never have. I am independent and strong-willed. That way, you survive.

"When I was a girl my mother would always be worried, 'What will people say?' And even then I would think, I don't give a damn. I always tell Tiger, 'You can't do things just to please other people. It will waste your energy, and you won't be happy in yourself. You have to do what is right for yourself.' And on that, he does a good job."

Her will is reflected in her speech, which is direct and blunt.

"With Tiger and me, no means no, and yes means yes," she says. "We don't need to talk a lot of b.s."

She opens conversations with declaratives like "Hey!" "OK" or "Now," that leave no doubt about who is in charge. When in agreement, she'll usually respond with a quick, "That's it," "That, exactly" or "You see?" Sometimes, after dispensing a sharp disagreement or criticism, she might extend her version of an olive branch: "Hey, I always tell you straight. That's me."

Further spicing up her English is a comical-for-its-incongruity saltiness that she learned from Earl, who enjoyed mixing in slang phrases -- the mildest of which, "dadgum," was a remnant of his Kansas childhood -- to make his points. And especially during her years in Brooklyn, where Tida worked in a bank, she picked up urban vernacular. She recalls her husband returning after a deployment in Vietnam and being astonished by the ease with which Tida was dropping street phrases, albeit with a strong Thai accent.

"It was so funny," Tida remembers. "He goes, 'Damn, now you're more sister than the sisters!' "And Tida can still lay it down. A question she considers too nosy might draw a brisk, "What the hell the matter with your ass?"

That's her attitude toward most probing questions. With approximately the same degree that her husband fostered the attention that came to him from Tiger's success, Tida has shunned it. She is especially loath to do or say anything publicly that will further complicate her son's hyper-scrutinized life. She is still scarred by an incident from a decade ago when she spoke to a Thai news service and was quoted as saying she would insist that Tiger's future wife be Thai. "The dadgum press got that wrong," she says. "All I said was that it would be nice. So, that's it -- no more interviews."

She has turned down all requests to be in commercials or advertisements save for one, which resulted in an eyes-closed hug with her son. "I only did that because Tiger had a contract he had to fulfill, and he specifically requested me." She accepted one Mother of the Year award as a favor to a friend who was part of an Asian-American organization, but after reading a prepared speech before an audience in Washington, D.C., she vowed, never again.

"My son knows what kind of mother I am, so why I need other people's approval?" she says. "You get a public life, you lose a lot. I want to be me."

The highest priority on privacy is just another way her son takes after his mother more than his father. "That's what I like -- mys-te-ry," she says, playfully elongating the word.

Of course, the litany of Tida's deeds on her son's behalf speak for her. In his most formative years, she was the one who drove him to tournaments, walked every hole and kept score, insisted that he do his homework before practicing golf, presented him with headcovers inscribed with "Love from Mom" in Thai ("Rak jak Mea"). For all the military ethos Earl passed along, Tida was the parent who administered the occasional spankings. She also navigated some tricky waters, on one hand enthusiastically exhorting her son to show no mercy when competing, yet still teaching him to be compassionate in daily life.

"In sport, you have to go for the throat," she says. "Because if all friendly, they come back and beat your ass. So you kill them. Take their heart." She pauses before adding, "I have that," aware that it describes her as a person for whom mustering compassion is not always easy.

Tiger has often said that it was "my mom, not my dad, I was scared of." And Tida can still get after him, though she has found that as Tiger has hit his 30s, guilt works best.

"When he doesn't call me for a long time," she says, "I might get on the phone and leave a message that says, 'Hey, Tiger, you remember the woman you used to call Mom? One of these days there won't be someone you can call that.' "

THE MISSION

Mostly because of the increasing pain from her own knee injury suffered several years ago after falling from a table while trying to hang a picture of her son, Tida rarely follows Tiger during his tournament rounds anymore. She even passed up walking during last year's U.S. Open at Torrey Pines, a veritable home game after the junior-golf days.

But otherwise, she remains as constant as ever. With the birth of granddaughter Sam, Tida became an enthusiastic baby sitter at home in California and during trips to Florida, and she can't wait to double up with Charlie. She even welcomes Tiger dropping off his two dogs, Taz and Yogi, which leaves her in care of six. When Tiger moves to his Jupiter Island estate sometime next year, Tida will move into a home a few miles away that will feature plenty of acreage to run the dogs.

Simply put, her son is her life. She knew she would be a devoted mother, but it upped the ante when doctors told her after Tiger's birth that she would be unable to bear more children. She never let up as a parent, never took a job even when money was tight, never hired a baby sitter. She says part of her reward has been her son's astounding success, but the biggest part is his trust and love.

"I always told him, 'You can always count on Mom. Mom will never lie to you.' Every night I pray to the Buddha, that in the next life Tiger will be my son again."

Still, there is mystery. Who is this mother whose son somehow has everything in place mentally and emotionally? What drove her to make sure her son always got all of her and more, and in the process gets so many things right? Why was she on such a mission?

On the long road back to Bangkok on the day she rode the elephant, Tida told a story of redirected pain and vowed that she would be different from her parents.

"After they divorced, it was hard for me," she says. "When I was put in the boarding school, for five years I almost never went back to any of my family, just stayed at the school. Every weekend I'd hope my father or mother would visit me, or my older brothers and sister, but no one ever came. I felt abandoned."

As a pre-teenager alternating between the separate homes of her father and mother, "I preferred to be with my mother," Tida says. "But she had other children after remarrying, and I was nothing to my stepfather. My father also had other children with his new wife, and they were considered more important. My father, he never hug me or tell me, 'I love you.' So when I returned to Thailand from the U.S., I would hug him and say, 'I love you.' That's why I always hug Tiger and tell him I love him. Because I didn't have that.

"Tiger know his grandmother a little, so that was good, but my mother never understood me," she says. "I tried to break the wall, but I couldn't." Her mother died in Thailand in 1985, her father in 1998.

"Now that Tiger is older, he has his own children, and he knows more about how life is, and he looks at me differently," she says. "The other day he said, 'Mom, you were so strong.' And that felt so good, and I was so proud of my son that he understands me."

Of Tida's three full siblings, two are still alive, and she visits them when in Thailand.

"They think I'm OK. That's it," she says.

On the way to see her eldest brother, Gayee Punsawad, 74, the father of Pong and Tida's niece, Peau, 46, who lives with her in the United States, we stopped at the town temple that was designed by Tida's father and finished a few years ago with funds provided by Tiger. Gayee, who runs a general store, suffers from the same nasal congestion and cough that troubles Tida, and the day before he had coughed so violently that he had lost consciousness and fallen, cutting his forehead. The two siblings hug and talk for a few minutes, and then Tida signals that it's time to leave.

"We get along fine, but we are not really close," she says. "That's the story of my family. Hey, we are all old now. What happened, it's over. It's gone. What the heck. Have to forgive and forget and live in present."

Her real focus in Thailand is on the two schools she is helping. At the convent school, 44 nuns care for 300 girls, many orphaned or abandoned, some sexually abused, some rescued from Thailand's sex trade. The small dormitory can accommodate only about 50 girls, so the rest sleep in the classrooms. Tida, who has included the school in her will, offers words of encouragement to the girls and watches intently as they interact, some walking arm in arm or hugging. "When these kids get here, a lot of them don't talk," she says. "It takes a while. Only each other can understand what they been through."

At the school for the mentally disabled children, the scene is sadder. Of the 97 children, only a few are claimed by parents, and most are severely challenged enough to require constant help from the 10 therapists and other staff. As Tida walks among the children dispensing candy, one 8-year-old boy is especially insistent in reaching out to her, and as she holds his hand he begins to talk loudly and laugh.

"He called me Mom," she says, looking back at her group. "You know, we all want the love."

I was brought back to an earlier conversation, when Tida discussed her tough exterior.

"I don't show emotional," she said. "Even when Tiger win at Masters first time, and the old man sobbing, I was very happy but not break down. At U.S. Open at Pebble Beach, on Sunday when all the people on the fairway bowed to him, I think, That's nice, but that's all. Only at St. Andrews, when Tiger win his first British Open and finish the Grand Slam, when he was coming up the last hole of the Old Course, which is so much history, and all the people are waving and applauding, and I thought, That is my son. I got a damp in my eye. It just come up."

She's still holding the boy's hand when a damp comes up again.

For more information on the Buddhist Girls Convent School for orphaned and abused girls and the Ratchaburi Home for Mentally Disabled Children, please visit tigerwoodsfoundation.org