News

Cover Story: The Story Of Rory

Amid the steel beams and industrial chic of a vast Chelsea Piers gym on the West Side of Manhattan, Rory McIlroy is right at home—high-tech fitness shirt straining across his broad back, vein-popping forearms, sharply defined jawline, curly locks cropped close. Everything is sleek, strong and stylish. McIlroy is 25, and the mop-haired, slightly puffy, rosy-cheeked cherub who a few years ago couldn't stand on one leg for more than a few seconds is gone.

McIlroy is in full workout regalia in one of his favorite cities not because he's meeting his sport scientist/ trainer, Dr. Stephen McGregor, for one of their intense 90-minute sessions, but because he's doing a photo shoot for the brand of headphones he endorses. But when an assistant brings a spray bottle to McIlroy to simulate perspiration, the world No. 1 politely declines before hopping on a spinning cycle to churn hard for a full five minutes. The moisture he raises could have been produced with a few well-placed spritzes, but McIlroy is pleased by the authenticity of his effort. With the same playful pride from the week before, when he tweeted a photo of himself lifting 280 pounds, accompanied by the message, Better never stops, he points to his damp shirt and says, "That's earned."

There is no zealot like a convert, and these days McIlroy is willing to invest whatever sweat equity will get him to the highest reaches of excellence. Last year McIlroy got busy like no other time in his life, following the direction of McGregor, swing instructor Michael Bannon and putting coach Dave Stockton. Even more, McIlroy reawakened his passion for golf. "It's what I think about when I get up in the morning," he said after winning the British Open at Hoylake. "It's what I think about when I go to bed."

photo with the message, Better never stops.

That mind-set might have evolved slowly, but history will mark it as the moment McIlroy publicly broke off his engagement with Caroline Wozniacki May 21 at the BMW PGA Championship at Wentworth. Five days later, when he came from seven shots down in the final round to get his first win in Europe or America in 18 months, he appeared a new man.

Even after the victory, McIlroy was understandably subdued. But it wasn't long before he set a new course.

"After [the breakup], I thought, What else do I have in my life?" he says during lunch at the downtown Standard, High Line. "I have family and friends, but they're always going to be there. What else? That's when I decided, You know what, I'm just going to immerse myself in golf for a while. I spent more time at it, thought about it more, spent more time at the range and at the gym. Because that's all I had, and that's all I wanted to do."

McIlroy takes a forkful of his Atlantic salmon with a side of Brussels sprouts, a meal approved by McGregor, and explains how as a golfer, he has become decidedly anti-slacker.

"I've come across enough successful people now to know that the best in whatever walk of life, they're the ones who just work the hardest. I realized that if I want to be the best and fulfill my potential, I'm going to have to do the same thing. And for those who are lucky enough to be born with a gift and then choose to work the hardest—I mean, that's the combination."

Photos: Rory Mcilroy/Twitter, Richard Heathcote/Getty Images, Peter Muhly/AFP/Getty Images__

AFTER A MONSTER 2014, BIGGER GOALS IN 2015

In 2014, the payoff was big: two major-championship wins, one grinded out on the links at Hoylake, the other won with a desperate sprint from behind in the PGA at Valhalla. In their way, both were more impressive and confidence-building than his eight-stroke victories at the 2011 U.S. Open and 2012 PGA, which were blinding blasts of pure talent that testify to McIlroy's ability to dominate when he's on. But those first two major victories did not truly test him in a final-nine crucible. For good measure last year, McIlroy administered a no-mercy 5-and-4 beating of friend and rival Rickie Fowler in Ryder Cup singles, a match in which McIlroy started six under through six holes.

This year, the payoff target is even bigger: victory at the Masters, which would give McIlroy the career Grand Slam, his third major in a row, and a chance at the Rory Slam in the U.S. Open at Chambers Bay.

At first glance, McIlroy should be the favorite at Augusta. The kind of driving he exhibited at Hoylake and Valhalla—where he led the fields with averages of 328 yards and 316 yards, displaying the best seen in back-to-back major championships since Tiger Woods won the 2000 U.S. and British Opens—has been a key determiner at the Masters. McIl-roy dominated the PGA Tour last year in strokes gained/driving, and the player who finished second was Bubba Watson, who has ridden his driver to two of the past three green jackets.

Karim Sahib/AFP/Getty Images

But there is evidence to support why McIlroy might not win at Augusta. In his six Masters, last year's T-8 is his best finish (see chart). In those 22 rounds, he has made an astounding 11 double bogeys and three triple bogeys. Just as amazing, considering McIlroy's length, his cumulative total on the par 5s is only 21 under. Although scattershot short irons have been responsible for most of his big numbers, McIlroy has had trouble on the iconic greens, consistently finishing in the bottom half of the field in putting.

"A firm and fast Augusta, or a typical U.S. Open setup, is probably the most difficult test for me," he says. "It requires so much discipline and precision, and that's something I'm still learning. I won a U.S. Open, but it was much wetter than normal, and even Hoylake was soft for a links. So if Augusta is fiery, winning there would get me closer to being a complete player, because I don't think I'm there yet."

That's a measure of how much better McIlroy believes he can become. Another wrinkle is the way he celebrates rather than squelches the memory of his worst day in golf, the final round of the 2011 Masters, which he entered with a four-stroke lead but shot 80 to finish T-15.

"It was the most important day of my career, bar none," McIlroy said in January. "I learned what I shouldn't do when I'm in that situation again." Indeed, the next major, he won by eight strokes at Congressional, finishing with a 69.

TRUSTING THE THREE WISE MEN

Since then, and especially lately, there has been a lot McIlroy has learned he should do. In particular, trusting the wisdom and guidance of the performance experts who advise him.

The most cutting edge is McGregor, 41, an Englishman with a Ph.D. in exercise physiology who has worked with the New York Knicks and the Manchester City soccer team and directed Lee Westwood's physical transformation. McGregor started working with McIlroy in 2010, when the golfer began experiencing lower back pain.

"When we started, Rory had never done any physical training," McGregor said while following McIlroy at the Australian Open last November. McGregor has designed regimens—90-minute sessions 10 times a week—that primarily strengthen McIlroy's core and lower body but which have dramatically improved his overall fitness. "Rory possesses hyper-flexibility and has extraordinary hip speed," McGregor says. "To get more control and consistency, he needed to build body stability."

The trainer, who is a casual golfer, works closely with Bannon to see what swing adjustments the instructor is implementing. "We find out the golf swing he wants to achieve and change his body accordingly," McGregor says. McIlroy confirms that his improvement—a 5-mile-per-hour increase in clubhead speed since 2010, up to 121.56 mph, with more consistency—has come from his body getting stronger and faster rather than through any changes in technique.

"My swing has lost its whippy sort of action that came from a lot of arm and hand speed," he says. "Now it's more the big muscles controlling rotation, and that's the energy that's going into the ball."

Bannon has been McIlroy's only swing coach since the two began working together at Holywood Golf Club outside Belfast when Rory was 8. With a kindly, soft-spoken manner and a visage that evokes Paul Newman in "The Verdict," the 56-year-old father of four says, "I have no idea why our chemistry has worked. I just like Rory. And I love to help him play the kind of golf he can."

Bannon was a good player in Northern Ireland—he lost a playoff to Padraig Harrington in the 1997 Irish Professional Championship—but made his name teaching promising juniors at Bangor Golf Club. (Since 2012, he has worked full-time for McIlroy.) In the video studio of the club, Bannon pulls out old tapes of his charges, including one of a certain ruddy-faced 8-year-old.

"Always a happy man, Rory," Bannon says of the smiling figure swinging a cut-down iron. On the tape, the instructor can be heard to gently implore, "Now hold your balance at the finish," which is the mantra behind McIlroy's ability to repeatedly stick his majestic follow-through. "There was nothing that was good at 8 that I took out," Bannon says. "I always wanted him to go away from a lesson with just one thing, not loads of things. Rory listened to everything and was very good at taking the lesson home and coming back having learned."

These days, "I keep an eye out," Bannon says. "Mostly small things. He can get a little off with his takeaway, lift it outside or pull it inside, or over-correct either way. But when he gets his lines, he's pretty hard to contend with."

The mystic on the team is Stockton, 73, who has worked directly with McIlroy about a dozen times since they first met a few weeks after the 2011 Masters. "I told him he was lifting out of his crouch and moving too quickly to the ball," says the two-time PGA Championship winner, who emphasizes the importance of seeing the line and "walking into" a putt rhythmically. "He corrected that at Congressional."

Stockton's interactions with McIlroy have usually consisted of passing along musings on demeanor and walking pace, with only minimal work on the stroke, although McIlroy uses the Stockton-endorsed concept of "spot putting," rolling his ball over a visual spot about an inch in front of the ball.

Last season, McIlroy served as his own putting coach, with Stockton on call if needed. On the PGA Tour, McIlroy went from 117th in strokes gained/putting to 41st. "He told me, 'I've got it. I'm a good putter.' And he is," Stockton says. "He's the easiest student I've ever had because he needs next to nothing technically. As long as he keeps himself in the right frame of mind, I don't think putting is ever going to be an issue for him. What I see now is Rory having put things together mentally. As physically gifted as he is, I think the other players are in a world of hurt."

There's little doubt McIlroy is perceived as a tougher, more mature, more prepared, more clutch player than he was before. Though the aesthetics of his game have always drawn raves, from Johnny Miller citing the "Adonis follow-through" to Geoff Ogilvy's opining that "Rory's shots make the best noise, more flush even than Tiger's at his best," the book on McIlroy among peers was that he lacked the grit to grind out victories when he wasn't "on." But with last summer's performance, McIlroy has earned locker-room cred. "Rory's got guts," says Jim Furyk. "He doesn't back down."

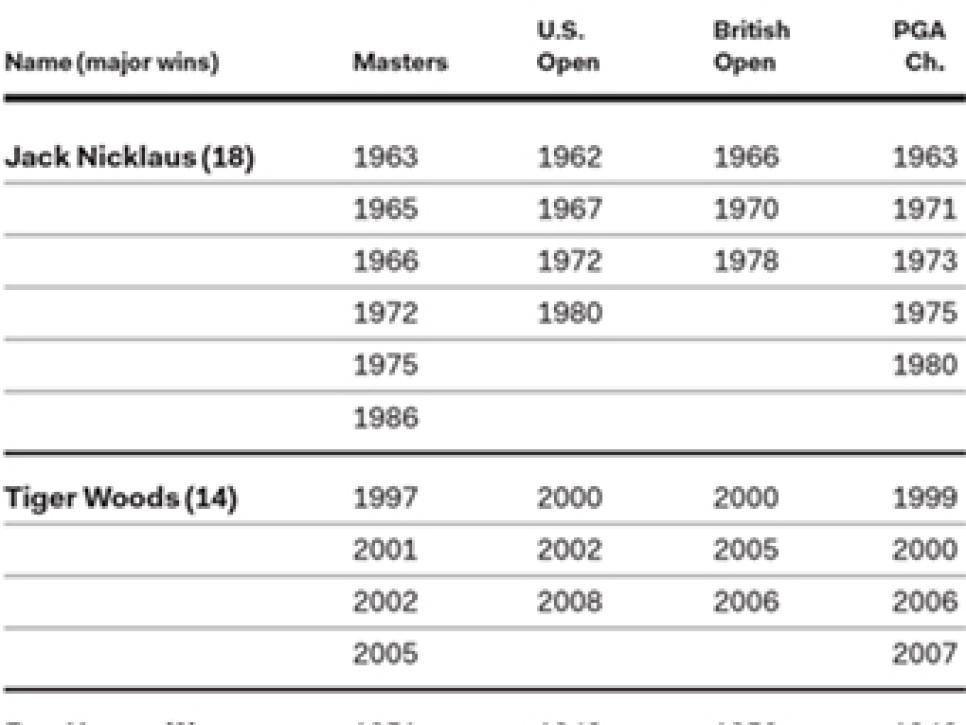

McIlroy is being seen as the kind of special player who can summon the will to seize the biggest moments. Augusta will be one of those, and if McIlroy pulls off the victory for the career Slam, he'll join Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan, Gary Player, Jack Nicklaus and Woods in a most exclusive club.

Photos: Stephen Szurlej; J.D. Cuban; Caroline Wozniacki/Twitter__

ACCEPTING HIS GENIUS

Like Bobby Jones, another amiable prodigy who had some lean years in his early 20s, McIlroy is a complex bundle of contradictions who, as he confesses, took a while to reconcile the power and price of his genius.

"Until just a few years ago, I don't want to say I felt guilty for being successful because I had this ability given to me, but it was sort of like, 'Why me?' " he says. "Because I felt like it's a very selfish thing to be a winner, a very selfish trait. Which is what you sort of need in golf. And I guess it just took me a while to be comfortable with that, just because of the personality I have. I realized that if I want to succeed in golf, which I do, I need to have it. What helped was realizing how much people like winners, how people gravitate to them. So if other people are happy for me winning, then why can I not be?"

After a sip of a diet cola—"my treat"—he continues.

"Now I want to win at golf all the time. I feel like golf has allowed me to be competitive at something in life—and my fitness has become part of that—and I feel like I've developed a bit of a ruthless streak on the golf course over the last few years. But I've no real ambition to be the best at anything else. If we're playing a game of cards, or a game of pool, or whatever it is, I'd happily let someone win just to keep them happy."

Such talk by a professional athlete in a culture that reveres 24-7 competitors nearly begs for an intervention led by Michael Jordan. But McIlroy is very close to his father, Gerry, a bartender whose credo is, "It's nice to be nice, and it doesn't cost you a penny." The people-pleasing example stuck, even though the increasing demands of his station can seem like a bottomless pit. "It's a natural tendency for me to be too nice," Rory says. "To be a little too giving to be able to focus on what you need to do, and sometimes I have to cut that back." Here he mentions his mother, Rosie, an introvert to his father's extrovert. "Sometimes," Rory says, "I wish I had a little more of my mum's reserve."

In January, when a McIlroy tweet defended Seahawks running back Marshawn Lynch's recalcitrance with the media—Love this! Paid to play, not answer questions—it seemed a way of venting about the claustrophobic coverage of his dating life and the rest of his off-course activity and commitments. "Time has become his most precious commodity," says Brian McIlroy, one of Rory's uncles. "He is absolutely delighted on those days when there is nothing he has to do."

One thing that had threatened to take a great deal of time was McIlroy's lawsuit against his former management at Horizon Sports, which claimed that he was coerced into signing an "unconscionable" contract at a Christmas party. Horizon countersued, claiming breach of contract for unpaid fees.

In early February, on the eve of a trial that was estimated to last six weeks and possibly longer, the parties settled, with McIlroy agreeing to pay an undisclosed sum. According to Golf Digest's Ron Sirak, McIlroy has earned more than $125 million on and off the course through last year. In 2014 alone, he made more than $49 million.

"He isn't afraid of the lawsuit, however it goes," Brian McIlroy said in December. "Rory told me, 'I want it to sting. It will remind never to make that same mistake again.' "

McIlroy has remained cooperative with the media, and often expansive in his press conferences. He continues a sure touch with small grace notes, sending thank-you cards to pro-am partners and tournament officials, and he tips locker-room and security people personally with no regard for how he played. Says longtime Florida golf executive Andy O'Brien: "If you asked the cart guys at the Bear's Club who their favorite is among all the sports-celebrity members, it would be Rory, unanimously. He's the real deal when nobody's watching."

Is he being too nice? It raises the question that pertained to Arnold Palmer in his heyday: Will the very thing people love about McIlroy keep him from being what they—and he—most want him to be, a great winner?

Just as McIlroy is welcomed in some quarters as a respite from the imperial edge of the Woods era, so is he doubted for lacking the same quality. Ironically, probably no other current player has scrutinized Woods more than McIlroy. He happily presented himself as a "Tiger Woods expert" during a 2009 interview with CNN.

"I studied him a lot—a lot," McIlroy says. "I mean, his instruction book, How I Play Golf—when my dad was driving me all over Ireland for boys tournaments, I would sit in the front seat and just read that thing. It was my bible. I know every major Tiger's ever won, where he's won them, how many he won by, who finished second."

The two have become friends, occasionally playing rounds together at the Medalist in Florida. Observers report that they like to needle. After Greg Norman suggested in 2012 that Woods was intimidated by McIlroy, Tiger playfully began calling Rory "The Intimidator."

"He's great with me," McIlroy says. "He's very... actually, he wants to help. He's like, 'I know you're getting into the same sort of position as me, so anything you need to know, we've been through it all.' "

Photo: Charles Laberge

LEARNING FROM NICKLAUS

Though McIlroy has used Woods' example as near-equal parts inspiration and cautionary tale, he has more actively sought the counsel of Nicklaus, who likes being a sounding board, just as Bobby Jones enjoyed imparting wisdom when Jack and his father would visit him at the Masters in the '60s. By McIlroy's and Nicklaus' accounts, conversations have been lively on a wide range of topics. But perhaps because things change, they haven't discussed McIlroy's goals.

"Rory is good enough to achieve whatever he wants in his career, but I don't know what Rory really wants—he hasn't told me, and I haven't asked," Nicklaus says. "He may be fairly happy to go along and win one major here, another major there, or he may want to work really hard and win a bunch. In my career, those goals fluctuated. Every player's got to find his balance between ambition and sanity. Now, were major championships my focus? Yes. Were they my sole focus in life? No—my family was always before that. Could I have worked harder and won more majors? Probably. Could I have driven myself crazy doing it? Absolutely. The choices a player makes are personal, and they evolve with life. And Rory will make his."

For now, McIlroy has chosen to work hard and win often. But for how long? After he broke up with Wozniacki, he told himself to "immerse myself in golf for a while." Could that mean his increased commitment will be short-term?

"No," McIlroy answers quickly. "I've realized this program is what works for me. This is what I need to do to be my best, so I'm going to keep doing it."

One thing the program doesn't include is drastic change. Without saying so, McIlroy clearly is not following Woods' playbook. At 165 pounds on a 5-9 frame with body fat of only 10 percent, McIlroy says, "I'd like to put on another 10 or 12 pounds. That will happen over time. It would be functional. The more mass you have in the body, the more mass you can transfer into the golf ball. It's simple physics. If I was going to put any muscle on, it would be in my lower half anyway. I wouldn't want to get any bigger on top."

He's not going to change his swing. "If it ain't broke, don't fix it. That's my motto," he says. He's also careful about dramatically altering practice to focus on weaknesses like sand play (123rd on tour last year).

"You're not going to be great at everything," McIlroy says. "I think what a lot of guys do, which is understandable, is they really try to strengthen their weaknesses. And then they neglect their strengths, and even if the weaknesses get a little better, the strengths aren't as strong.

"The foundation of my game is my driving. When I drive the ball well, I win golf tournaments. So I'll always work on the driver."

McIlroy (with an assist from Watson) has returned the driver to its position as a key weapon of dominance. Though Woods played around driver inconsistency, McIlroy has harkened back to Nicklaus and Greg Norman (and the early Woods) in the way he has combined power and accuracy as the main point of separation from his peers.

In his last tournament of 2014, the Emirates Australian Open, McIlroy was obligated to play as defending champion but was so visibly tired that even his driver didn't work very well on the way to a T-15 finish. But after seeing that Jordan Spieth had shot a closing 63 to win by six, McIlroy tweeted: You could give me another 100 rounds today at The Australian and I wouldn't sniff 63. ... Well done.

"It was a very tough day to score," McIlroy says. "I just wanted people to know how good a round it was. And I like Jordan."

It's nice to be nice. Nick Faldo, who was McIlroy's first golf hero, tells a story of when a 12-year-old Rory was playing in the Faldo junior series.

"He had all the stuff you see today: an incredible full and free release of the club that gives him that very rare, true 100-percent strike," Faldo says. "But what most struck me was something else. At that time, my daughter Emma had just been born, and some of the kids had come over to see her and hold her. Fast-forward seven years, and I see Rory for the first time again at a tournament. The first thing he says to me is, 'How's Emma?' I found that extraordinary for someone who was clearly going to be a champion. He's able to do what so many of us couldn't or didn't during our playing days: Take the blinkers off and be a whole person. And he still does."

It's that attribute—if McIlroy ends up winning a lot of majors as big as this year's Masters—that might make him the most complete player of all.

5 TIPS FOR WORLD DOMINATION

What can you take from Rory's swing?

Based on his work with instructor Michael Bannon and trainer Steve McGregor, here are five concepts Rory has focused on—and how they can work for you.

1. PERFECT THE FIRST FEW FEET

In 2012-'13, Rory got in the habit of starting the club back to the outside. To compensate, he would sometimes drop it too far to the inside on the downswing.

In fixing this move, he'd overdo it the other way: a big inside-to-outside move. "I want him to swing his hands straight back for the first few feet, with the clubface looking at the ball, then let his body rotation take the club behind him," Bannon says. Try Rory's two-step drill: Swing the club back to hip high with your arms, stop, then turn your body to complete the backswing.

2. OBEY YOUR NATURAL RHYTHM

Great rhythm was something Bannon noticed in Rory early on and was careful never to tamper with. He says Rory's swing is a great model for flow. "It has a start and a finish, and no bits and pieces in between. It has no kinks." Many golfers see the swing in segments, and their rhythm suffers. By making a lot of freewheeling swings, especially when working on mechanical changes, you can preserve your natural rhythm. "Whatever Rory does," Bannon says, "he never loses the basic rhythm with it."

3. START SMOOTH FROM THE TOP

Another move Rory has worked on is a quiet transition. "The lower body brings the club down, then you can hit it hard," Bannon says. He's referring to the lateral move toward the target that starts the downswing. Rory used to drive his knees too aggressively, and the club would fall behind him. He now thinks of it as a small shift forward before the left knee quickly turns out of the way. Amateurs tend to try to hit the ball hard from the top with the upper body. Do as Rory does: Shift your lower body forward, then fire your arms through.

4. ALWAYS STICK THE FINISH

On tapes of childhood lessons with Rory, Bannon can be heard saying, "Hold your balance at the finish." To this day, one of the hallmarks of Rory's swing is the way he sticks the follow-through. Bannon says it's a good idea to think only about making a good finish: balance and pose. That can't happen without a lot of other good things happening first. It's also one of the easiest swing thoughts you can hold in your mind.

5. FIND YOUR WEAKEST LINK

Five years ago, McGregor did a comprehensive evaluation of Rory's body, identifying the weak parts as his legs and core. He designed an intensive program, and Rory has put in the work. Without any changes in technique, Rory's swing improved. McGregor says Rory's arms and hands used to move very quickly relative to his body, but now his swing is regulated by his big muscles, so the body and arms move together. It's a more efficient motion. Take a tip from Rory: Get your body working better, and your swing will follow.