News

Rumpled Genius

On a windy Wednesday in October 1860, eight Scottish golf professionals assembled to play a competition over three rounds on Prestwick's then-12-hole course. Willie Park Sr. of Musselburgh had rounds of 55, 59 and 60, good enough to beat the favorite, Old Tom Morris, by two shots, and earn the right to keep the ornamental red leather Challenge Belt, paid for by Prestwick members, for one year. There was no prize money. Thus was the Open Championship born. This year, at St. Andrews, July 15-18, the world's oldest golf tournament celebrates its 150th birthday, a magical congregation at the game's royal and ancient field of dreams; a homecoming.

The Old Course occupies a narrow strip of ground, about 2½ miles long, between St. Andrews Bay and the Eden Estuary. A flat, treeless wasteland at first glance, it is in truth alive with richness, medieval strangeness and peculiar landmarks with names like Hell Bunker, the Elysian Fields, Miss Grainger's Bosoms. This is a primordial landscape of infinite mystery, full of ghosts from centuries past; a golf course that is different on every outing; a puzzle that can never be solved or truly known. People have probably been hitting balls with sticks here ever since it was first granted as common land for the townsfolk in 1123. The right to play golf on the links was officially established in 1552. St. Andrews was described as a "metropolis of Golfing" in 1691. The 22-hole layout was reduced to 18 holes -- which thereafter became the norm -- in 1764. The long-raging Rabbit Wars were resolved in 1821, when a local laird bought off the rabbit farmers who also used the land and sent them away to seek their quarry elsewhere.

It's a course that used to be played backward (and, each year in April, still is), from the first tee to the 17th green, 18th tee to the 16th green, and so on. Prior to that, up to the early 19th century when the course was widened, it was played in single file, like a two-way, one-lane highway, with outgoing players on the front nine sharing each fairway and hole with incoming players on the back nine.

Today, all those shared double fairways and the seven vast double greens -- the putting surface for the fifth/13th holes is 100 yards long -- make it a terrible spectator course. There are lots of blind shots -- including one drive that must be played over a large, green shed. There are despicable, invisible pot bunkers in the middle of fairways. Out-of-bounds on most holes. A closing hole that's a short, bunkerless par 4 with one of the widest fairways in golf. The Old Course makes all the rules, and breaks them all, too. It is the first, best and last golf course on earth.

For this year's Open, the course will be 7,305 yards -- roughly 1,000 yards more than for its first Open, in 1873, when a good drive with a gutta-percha ball would travel all of 170 yards. (Today's leading players can double that.) New 2005 tees for the 13th and 14th holes are so far back as to be on a different property, the adjacent Eden Course. A controversial new tee this year for the already brutal 17th hole is 40 yards farther back, on a neighboring range. At St. Andrews, you used to tee off within a club-length of the hole into which you'd just putted out; nowadays, in the Open, competitors hole out and increasingly must take a brisk, 100-yard-plus walk back to the next tee. If driving distances were ever allowed to become so great that the Old Course were rendered obsolete, a museum piece unfit for tournament play, then golf will be a lesser game and its governing bodies will have failed.

For now, however, St. Andrews just about remains a relevant, demanding test for the best. Hitting a lot of fairways and greens is easy here; putting together a good 18-hole score is hard. Who will best negotiate these billowing curves and hollows come July? Who can answer the course's 18 challenging questions that live at the intersection of geometry and imagination, technique and feel, power and finesse, offense and defense, science and art, head and heart, yin and yang? Who will have luck on his side, the mysterious force of nature and karma, and be rewarded with implausibly fortunate bounces? And who will have sufficient emotional resilience? Because bad shots are punished here, and sometimes good shots are, too. There is no one to sue or referee to complain to when your seemingly perfect drive bounces and rolls into trouble. Just get on with it. Play the next shot. Take the injustice in your stride. You'll be a better golfer, a better person.

Some have managed it. The land should be littered with plaques commemorating stirring shots and great deeds from long-ago afternoons. James Durham shot 94 in 1767, a record that wasn't beaten until John Campbell Stewart shot 90 in 1853. Allan Robertson, golf's first professional, was the first to break 80, in 1858. Young Tom Morris did a 77. Bobby Jones shot 68 in the 1927 Open. Curtis Strange went 'round in 62 in the 1987 Dunhill Cup. When Tiger Woods won the Open at St. Andrews in 2000, his worst score was 69, his 19-under-par total is a championship record, and his eight-shot winning margin has been bettered only by Old Tom Morris in 1862 (13 strokes) and Young Tom Morris in 1870 (12 strokes) and in 1869 (11 strokes). In 2005, Woods won again, by five. His average score for those two past Opens at St. Andrews is 67.875. Despite his many errant strokes, loose play and poor management among all kinds of dangerous off-course hazards recently, the fallen hero is still the far-and-away favorite to win and become the first player to score three Opens at the Home of Golf. (Bob Martin, J.H. Taylor, James Braid and Jack Nicklaus all did it twice.) In early May, Woods led the betting with odds of 4-to-1, well ahead of Lee Westwood at 13-to-1 and Ernie Els, Padraig Harrington, Phil Mickelson and Rory McIlroy, all hovering around 20-to-1.

Tom Watson, 60, even at 250-to-1 is worth a punt only for those of an optimistic, sentimental and, OK, completely deluded disposition. He came tantalizingly close to winning last year at Turnberry. When his approach to the 72nd hole was in the air, he surely believed that he was about to win his sixth title, equaling Harry Vardon's record. Alas, a hard bounce, some disappointing jabs with the putter, and an out-of-gas playoff meant that the dream was over. There'll be many more broken dreams at St. Andrews this year. And plenty of magic, too.

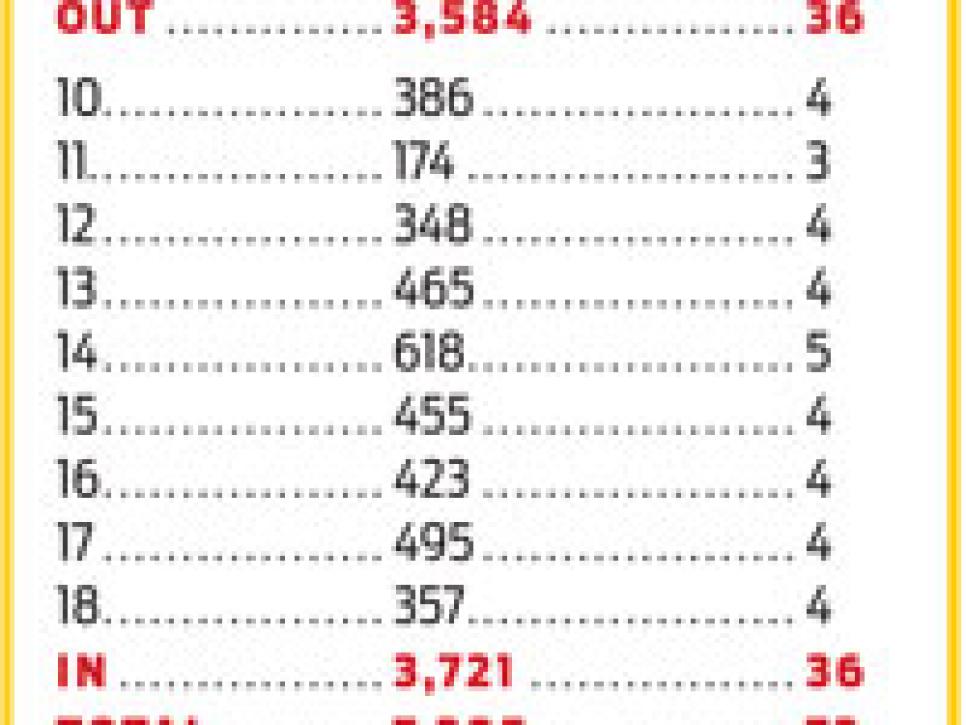

The par-5 14th (top) and par-4 fourth (bottom) share one of seven double greens.