In Search Of Seve

Jaime Diaz's profile of Seve Ballesteros originally appeared in the November 1990 issue of Golf Digest.

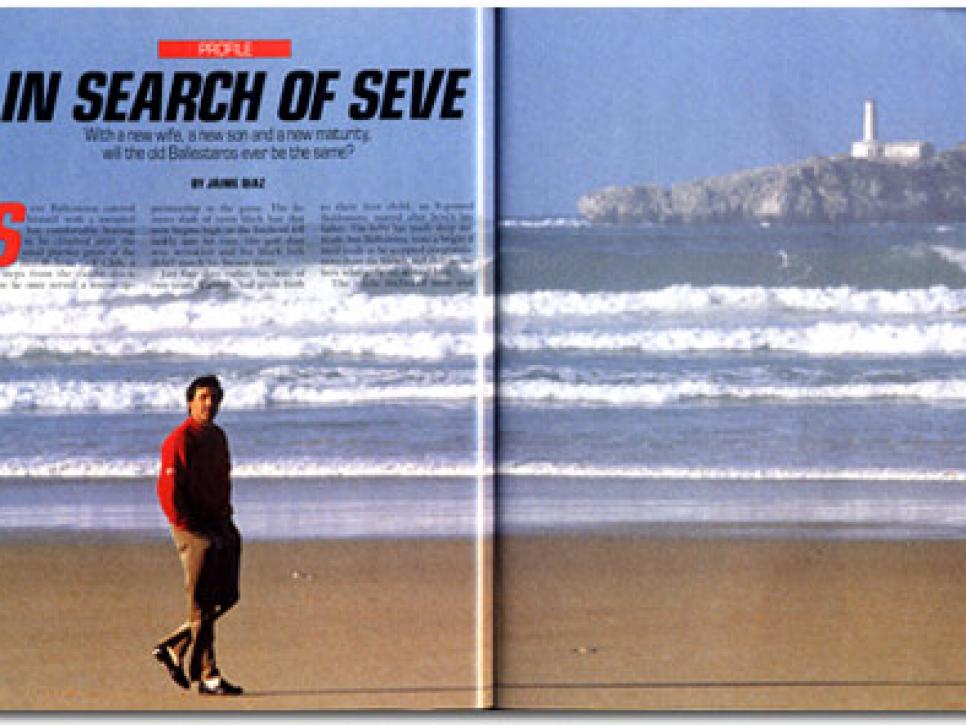

Seve Ballesteros carried himself with a rumpled, but comfortable bearing as he climbed on to the small practice green of the Real Pedreña Golf Club, a few steps from the caddie shack where he once served restive apprenticeship in the game. The famous slash of raven black hair that now begins high on the forehead fell lankly into his eyes. His golf shirt was wrinkled and his black belt didn't match his brown shoes.

[Ljava.lang.String;@3b431a44

Just four days earlier, his wife of two years, Carmen, had givenbirth to their first child, an 8-pound Baldomero, named after Seve's late father. the baby has made sleep difficult, but Ballesteros wore a bright if tired smile as he accepted congratulations from the friends and club members who gathered around him.

The circle included men and women he has known all his life, but Ballesteros seemed most at ease with the four or five children who anxiously sidled close to the group. He asked about the youths' golf games, commented on their outfits and smiled at their shy answers. Later, he chose a slightly overweight 10-year-old named Gabriel for the honor of shagging balls for him.

"You're a little heavy, so we are going to give you a workout," Ballesteros said to the boy in Spanish, drawing giggles from the other children and a grin from Gabriel.

Ballesteros, who officially lives in Monte Carlo, comes back to his birthplace of Pedreña, a seaside village of some 2,000 people in the north of Spain, about 10 times a year. Although he spends parts of most days working on his golf game, the bulk of his time in his birthplace is devoted to relaxation-cycling through the village lanes, fishing, target shooting, tooling around in a Volvo coupe, playing chess or cards with friends, or generally spending quiet time with his family in the simple country home he built for his mother, also named Carmen, near the golf course.

As he experimented on the elevated practice green for more than an hour with a Bulls Eye putter, his backdrop was the sparkling Bay of Santander, framed by its crowded beaches, and farther in the distance, rising on a narrow peninsula, the classic Palace of Magdelena, built at the turn of the century as a summer retreat for the king and queen of Spain. To his left, on top of a hill that overlooks Real Pedreña's front nine, is the two-story stone farmhouse in which he grew up, which is now the refurbished home of the family of his brother, Manuel.

Pedreña was a hard place to leave when the fire inside Ballesteros burned hotter than in any golfer in the world. Now that it no longer does, as he himself admits, the pull of his native land may be even greater.

"It's always been difficult for me to leave home," Ballesteros would say later. "For the Spanish people, it's not normal to leave where you were born. For Americans, it is more natural to leave, to go someplace else to find a good job. In Spain, the philosophy is to stay close to your family."

Ballesteros was speaking in the abstract, but there was a wistfulness in his tone that seemed to summarize the current state of his relationship with a game that has obsessed him since the age of 7. In his 17 years as a professional, Ballesteros has put himself at odds with his cultural and personal nature in his quest to be the best in the game. His five major championships and 60 victories around the world attest to a valiant fight, but it appears that the battles have left Ballesteros, at the relatively young age of 33, war weary and in need of repair.

The player who seduced the golf aficionados with a magisterial style marked by invention, courage and intensity is no longer considered the best in the world. The title has been inherited by the more prosaic but relentlessly efficient Nick Faldo, and among the contenders who have passed Ballesteros is Spaniard Jose-Maria Olazabal, the 24-year-old who in August transcended a record of precocious consistency with an explosive 12-shot victory at the World Series of Golf.

Meanwhile, Ballesteros, who won four major championships by the age of 28, has turned in two of the worst seasons of his career, winning only four tournaments in Europe and performing erratically in the majors.

And while other top players -- notably Sandy Lyle, Curtis Strange and Mark Calcavecchia -- are also suffering slumps, Ballesteros' long record of consistency and his passionate approach to the game makes his decline more alarming.

"Seve has a lot of reasons to be worn out," says Johnny Miller, who has been a friend of Ballesteros since 1976. "He's been a touring pro since he was 17, and he has carried a lot of baggage for a lot of years. He has had this tremendous drive to be the best, to set records, the extra pressure of being the favorite, and that can make you a little insane. His life is changing, and I'm sure he is wondering if golf will never have as big a role again. He is still a young man, but as far as golf, he is older than his age."

Commentator and former player Peter Alliss, a veteran Ballesteros watcher who recently angered the Spaniard by publicly opposing a move to hold the Ryder Cup in Spain in 1993, also cites the toll of the Spaniard's particular burden.

"He came in with a great deal of ammunition, but it's possible he may not have any left," said Alliss. "With as much globe-hopping as he's done, and as hard as he plays, he may have put into 14 or 15 years what someone else put into 25. It's too early to tell, but if he hasn't come roaring back by 1992, I would daresay then that it's probably come to an end for Seve."

[Ljava.lang.String;@46aa041

Making such an evaluation in 1990 would have seemed absurd after Ballesteros' victory at the 1988 British Open at Lytham. By winning his fifth major championship after a four-year drought, it seemed Ballesteros was ready to put the confidence-draining losses he suffered at the 1986 and 1987 Masters behind him and embark on his best years.

"Now I will remember instead how I played today," he said after his closing 65 beat Nick Price by two shots. "That was the best round of my life."

But since then, Ballesteros has played mostly mediocre and often nervous golf. The man Bernhard Langer once called "an intimidating player" is not scaring anyone. According to close observers, the gradual shortening of his swing has cost him distance, but not gained him a corresponding measure of accuracy. Even when he is playing well, the specter of the wild shot looms nerve-rackingly large. His short game seems to have lost some of its brilliance, and the palpable confidence he carried with the putter is only occasionally evident. And in the big moments he used to thrive on, Ballesteros has proved himself vulnerable.

"The things he used to do better than anyone else he has become only very good at," said one close observer. "And the things that he was always weak at have gotten worse." In 1989 he led the Masters after 63 holes but hooked his tee shot on the 10th into the trees, dunked a 6-iron tee shot into the water on the 16th and shot a 38 on the final nine to finish fifth. At the Ryder Cup, he was 1 down on the final hole to Paul Azinger when the American hit his tee shot into the water. Ballesteros, with a long iron to the final green, hit a thin approach that splashed in the hazard in front of the green to lose the match.

This year has been worse. After winning his only tournament of the year in Majorca in March, Ballesteros sank into a deeper slump that reached its nadir in late summer when he missed the cut at the British Open on the hallowed grounds of St. Andrews. Two weeks later, he shot 77-83 at the PGA at Shoal Creek, slamming clubs angrily into the Bermuda rough before exiting in a silent rage. It marked the first time in his career that he had missed the cut in two major championships in the same year.

But more than numbers, it has been the intangibles that have alarmed Ballesteros-watchers. The man whose big-cat grace was almost by itself enough to declare him the world's best has been projecting the body language and mien of a troubled, beaten nan. While the ages will be kind to him, in the last few years age hasn't been.

He is definitely brooding on it," said swing instructor David Leadbetter, who often acts as a sounding board for Ballesteros in his constant swing experimentation. "You can always see with Seve; when he is playing well, he is sort of prowling. Right now it's quite a grind for him to play. He doesn't look like the Seve of old, that's for sure."

It is a perception Ballesteros is well aware of, and as he sits down with a journalist on a bench next to the first tee at Real Pedreña to answer the inevitable questions of his recent demise, his manner is gracious but wary, his weathered brow furrowed.

"I know what some people are saying," he says in English that is clear despite his Spanish accent. "The only thing I'm trying is not to read too much about what is happening because it is no good. I try to avoid as much as possible talking about why this and why that and why."

Ballesteros says he does not see 1990 as the latest drop in a long fall from the top. Instead, he calls it the inevitable slump after years of hard driving.

"I got into trouble by pushing myself," he saId. After not much success in 1989, I was anxious to pick up the form, and I was trying too many things -- the grip, the ball position, the takeaway. Too many things. I got to the point where I was confused. Also, tired mentally. For some reason, my concentration has not been very good this year.

"Obviously, after so long, for many years, it must happen what happened to me. It's like you have never been ill, but sooner or later you will be, and this happened.

"I think I take it very good, and sometimes I get upset because I know I can do much better. But I know myself, and I know my mental power and I know I can recover. If I go slowly up with my confidence I can become the same golfer like four or five years ago."

Nonetheless, he has reached a point where he can admit that the curve of his career is no longer upward .

"Definitely my desire is not what It was," he admits. "That happens for everybody. You still want it, but not as much as you did before.

"This is natural. It's hard for people to understand that my life has not been very easy. I have many moments of glory, but I have many more, moments of very tough times. I don't mean anyone should feel sorry for me, but it's true."

Manuel Ballesteros, Seve's second-oldest brother, may understand his youngest brother's struggle better than anyone. Manuel, who played on the European Tour, was an early model for his younger brother's game, eventually giving up his own playing career to guide Seve through his early years as a professional.

"The problem of desire for Seve is a big one," said Manuel in Spanish from behind his desk at the Ballesteros management company, Fairway, S.A., located in a new office building In downtown Santander. "Even he admits his desire is not the same and he has said the truth.

"People forget he began so early. It s a gradual wearing down. Whether you admit it 0r not, it's there.

"When he plays poorly, his friends, even his family will say to him, 'So what? If you never win agaIn, you've already won enough.' They are trying to make him feel better, trying to take away some of his tension, but they are hurting him. It. plants a bad thought. After a certain time, he could relax. And to keep from relaxing at this point in his life is difficult."

[Ljava.lang.String;@7f530ed2

Of course, the addition of a wife and child into the life of a man who is the product of a society that treasures familial closeness could further lessen Ballesteros' drive to be the best.

Ballesteros has always been family oriented. His three brothers are all professionally involved in his career. The death of his father in March of 1986 dealt what Ballesteros says was a severe blow to his confidence and motivation as a golfer.

But Seve insists that his new responsibilities at home will not affect his approach to his career. "Nothing has changed;' he says firmly. "I will have more demands on my time, but everything else will continue in the same direction. I think it will help my golf, because I will get more rest when I come home."

Others wonder. One of the reasons that Ballesteros is popular in his home is that even though he has become an international celebrity, he has never shown any sign of changing his values. The people of Santander forgive him his obsession with his sport because they understand it is necessary for greatness, but they don't regard monomania as a permanent part of Ballesteros' character.

"Es muy de aqui (He is very much from here)," a clerk in his 30s at the car rental counter of the Santander airport says. He explains that Ballesteros has nothing to prove to Spaniards, that the country is more than proud that one of its sons is considered one of the game's all-time greats. In fact, Ballesteros is as much a topic of conversation for having married Carmen Botin, the daughter of Emilio Botin Jr., the richest man in Santander and one of the five richest in Spain, as he is for his golf "Ya a demonstrado bastante (He has shown enough)," says the man. "Y ahora, con un hijo? (And now, with a son?)" The clerk shrugs.

On the 20-minute ride on the open ferry that connects Santander with Pedreña, two 14-year-old girls whose families belong to Real Pedre#241;a say that Ballesteros is often a topic of conversation. "My father says he hasn't played well since he got married," says one girl. Her friend comments on Ballesteros' good looks, but adds, "His wife must be a good cook, because it looks like he's put on weight."

Others closer to the game point out that Ballesteros would be the exception among modern great players if he were not to have married and had a child. They say the added perspective and maturity that comes with fatherhood may actually improve his game. "Those things are all positives;' says Gary Player. "They settle a player down."

The real problem, according to Player, is with what is both a model of elegance and a labyrinth of complexity-Ballesteros' golf swing.

In his quest for perfection, the largely self-taught Ballesteros has changed his game significantly over the years. From the powerful slasher with a huge turn whose club used to finish straight up in the air to keep from hooking, Ballesteros has changed to a shorter, flatter swing that produces a classic finish. But despite his more compact motion, Ballesteros has continued to fight the wild shot that has driven him to distraction and a loss of confidence.

"He probably knows more about the swing than he should," says Miller, who believes Ballesteros has encountered some of the same dilemmas that plagued his own career. "The first thing he should do is tell all his swing thoughts to take a hike. With so much in his head, he can't play Seve golf. He might be seeing Faldo doing so well with a mechanical approach, but Seve is a different type of player. He has to be intuitive. If I were his teacher, I would tell him, 'There's the ball, there's the target. Now, play. Let the target be your swing.' "

Player, a man Ballesteros regards as a hero, and whom he approached for swing advice at the British Open, says that Ballesteros has gotten lost in his search for a better technique.

"Seve is suffering from paralysis by analysis," says Player. "He has realized that he is not the straight hitter he would like to be, and he has meddled around for changes and he's lost confidence. He's no longer sure of his fundamentals."

Player believes the root of Ballesteros' problems began when he realized in the early 1980s that the swing that won a British Open and a Masters was not controlled enough to win a U.S. Open.

"Seve has never had what I would call the best mechanics in the world," says Leadbetter, who has gained fame as the architect of Nick Faldo's seemingly airtight game. "Seve has many exceptional qualities -- his rhythm, his sense of timing, his general fluidity, the way he always sets up to the ball great. So many great pluses, but he also has some minuses. No question the flaws in his technique are starting to show. Right now, he seems to be fishing in the dark."

Leadbetter believes that the root of Ballesteros' problem is his fear of hooking the ball. His career pattern to combat what Leadbetter calls "the left shot" has been to keep his head and upper body well behind the ball coming into the impact area and dropping the club into a plane dramatically inside the target line. But Leadbetter says such a move puts Ballesteros into such a "steep" hitting position that he is forced to use his hands too aggressively through impact. The result, says Leadbetter, is a high number of off-line shots.

"I think he is not as strong as he used to be, and he needs strength to be able to hold off the left shot. He told me at the PGA that his back was acting up and he couldn't practice as much. Now, to my mind, his swing looks positively sloppy. His hands are controlling his body instead of his body controlling his hands;' he says.

Ballesteros has heard such advice before, and is leery of making major experiments when his basic swing, flaws and all, has carried him to the top of the game.

"A lot of people come up to me and say, 'Let me give you a tip,'" says Ballesteros. "I tell them, 'My house is already full of tips.' Once you reach 30, I don't think you can change your basic swing. And why should I change my swing? It's been good for 15 years."

Although he respects Leadbetter and the accomplishments of Faldo, he considers the Englishman's dramatic ascent more a result of mental discipline than swing mechanics.

"If you watch tapes of Faldo five years ago, I really don't think his swing has changed very much,' says Ballesteros. "The key in Nick Faldo is that he conquered his mind. I know that very well because I have had my time, too. Once you conquer your mind, everything looks very simple, very easy, and you feel the best, and you feel you can beat everybody. That is what has happened to Nick Faldo at the moment. There is nothing that I see with him that I don't have."

Whether Ballesteros can ever conquer his golf mind to the extent that he did as an obsessed and eager single man may be the greatest challenge he has faced in his career.

The emotional cost of playing big-time golf has always been high for Ballesteros. He has said that when he wins, he weeps happy tears, and when he loses, he weeps sad tears. Then there is his lifelong battle to suppress an explosive temper.

"One thing I have against myself is my hot temper,' Ballesteros says, shaking his head resignedly. "I get upset very easy, and once I play I have to fight against the game and my character, myself, many times. I have improved, but I need to improve even more."

In another area, Ballesteros may need to regress. In his recent book, Natural Golf, Ballesteros wrote that the competitive bubble he enters during a major championship is "a reincarnation of the young and supercompetitive Seve who has to make it at all costs. I was literally back in my adolescence."

But as he ages into fatherhood, it will become harder and harder to enter a bubble of arrested adolescence.

"I always felt the obsessive bit was overdone, not really his character" says one longtime observer of Ballesteros. "He has felt he had to be that way to win, but it was unnatural. I think as he gets older that quality is going to lessen as he settles into a more normal life."

How long a wealthy Ballesteros can continue to commit to the all-consummg life of professional golf in the face of an existence that holds contentment and balance is problemtic. He is already fighting the theory that even the game's greatest players, with the exception of Jack Nicklaus, only have five years to play their very best golf. Ballesteros' most fertile period was from 1979 to 1984. To enter a new prime goes against history, and against the odds.

"The question is really whether Seve wants to continue to give up as much as he has given up to become what he is," says Tony Jacklin. "It takes its toll. I know. I was there."

"Seve is bored," says his manager Joe Collet. He is from a small town, he likes to be with friends and traveling has always been hard for him Right now, playing tournaments i toil instead of a thrill."

But Ballesteros is convincing when he says he still wants to win golf tournaments, most of all the U.S. Open and the PGA which would complete his goal of a career Grand Slam .

"I think I deserve more majors" he says. "And I think I will get them. How long it will take, I don't know. But I know It will happen."

It is that basic determination, the one that took a farm boy who spent hours hitting rocks with a hand-wrought 3-Iron on the beaches of Pedreña to the game's apex, that makes those who know him best believe that Severiano Ballesteros is far from finished.

"I know the character inside of Seve," says his brother Manuel "I know he still has a dream. Now his wife and child can be part of his dream. He can want to reach the top again for them."

Ballesteros affirms that he does indeed have a vision of greatness for himself. But he also acknowledges that life is not as simple as it was. Will he be able to live his new life and still have his dream?

He ponders the question as he drives past his boyhood home stopping to point out the spot near the farmhouse from where he used to launch 3-iron shots at twilight onto Real Pedreña's second green. He remains silent and thoughtful as he drives the Volvo along the coastal road that wraps around Pedreña turning toward the pier where his guest will meet the ferry for a short ride back to Santander. After stopping the car, he raises his eyebrows, purses his lips, and stares into the distance. Finally, he answers.

"That's the thing," Ballesteros says, "I'm going to have to figure out."