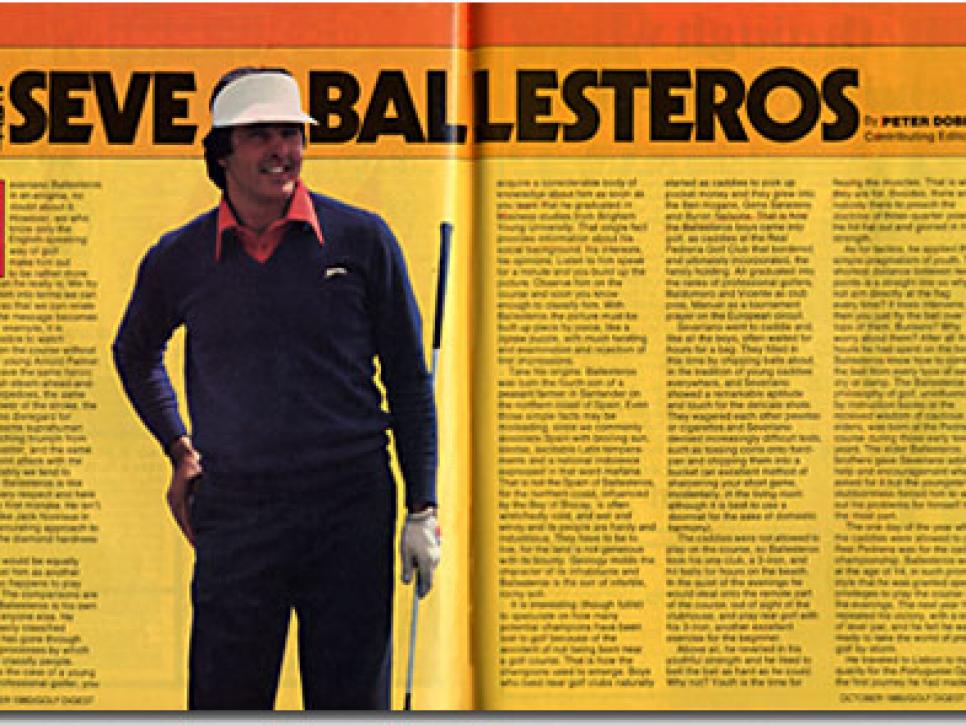

The Enigma Of Seve Ballesteros

Peter Dobereiner's profile of Seve Ballesteros, originally published in the October 1980 issue of Golf Digest.

Severiano Ballesteros is an enigma, no doubt about it. However, we who know only the English-speaking way of golf make him out to be rather more enigmatic than he really is. We try to translate him into terms we can understand, so that we can relate to him, but the message becomes garbled. For example, it is scarcely possible to watch Ballesteros on the course without recalling the young Arnold Palmer.

Here we have the same heroic attitude of full-steam-ahead-and-damn-the-torpedoes, the same explosive power of the stroke, the same feckless disregard for danger, the same suprahuman feats of snatching triumph from apparent disaster, and the same arrogantly bald attack with the putter. Inevitably we tend to assume that Ballesteros is like Palmer in every respect and here we make the first mistake. He isn't. He is more like Jack Nicklaus in his coldly calculating approach to golf and in the diamond hardness of his will.

And yet it would be equally as wrong to label him as another Nicklaus who happens to play like Palmer. The comparisons are superficial. Ballesteros is his own man, unlike anyone else. He cannot be easily classified because he has gone through none of the processes by which we normally classify people.

If you take the case of a young American professional golfer, you acquire a considerable body of knowledge about him as Soon as you learn that he graduated in business studies from Brigham Young University. That single fact provides information about his social background, his interests, his opinions. Listen to him speak for a minute and you build up the picture. Observe him on the Course and soon you know enough to classify him. With Ballesteros the picture must be built up piece by piece, like a jigsaw puzzle, with much twisting and examination and rejection of first impressions.

Take his origins. Ballesteros was born the fourth son of a peasant farmer in Santander on the northern coast of Spain. Even those simple facts may be misleading, since we commonly associate Spain with broiling sun, siestas, excitable latin temperaments and a national indolence expressed in that word manana. That is not the Spain of Ballesteros, for the northern coast, influenced by the Bay of Biscay, is often wretchedly cold, and wet and windy and its people are hardy and industrious. They have to be to live, for the land is not generous with its bounty. Geology molds the character of its inhabitants and Ballesteros is the son of infertile, rocky soil.

It is interesting (though futile) to speculate on how many potential champions have been lost to golf because of the accident of not being born near a golf course. That is how the champions used to emerge. Boys Who lived near golf clubs naturally started as caddies to pick up pocket money and they grew into the Ben Hogans, Gene Sarazens and Byron Nelsons. That is how the Ballesteros boys came into golf as caddies at the Real Pedreña Golf Club that bordered, and ultimately incorporated, the family holding. All graduated into the ranks of professional golfers, Baldomero and Vicente as club pros. Manuel as a tournament player on the European circuit.

Severiano went to caddie. and, like all the boys, often waited for hours for a bag. They filled in this time by chipping balls about, in the tradition of young caddies everywhere, and Severiano showed a remarkable attitude and touch for the delicate shots. They wagered each other pesetas or cigarettes and Severiano devised increasingly difficult tests, Such as tossing coins onto hard-pan and chipping them into a bucket (an excellent method of sharpening your short game, incidentally, in the living room although it is best to use a doormat for the sake of domestic harmony).

The caddies were not allowed to play on the course, so Ballesteros took his one club, a 3-iron, and hit balls for hours on the beach. In the quiet of the evenings he would steal onto the remote part of the course, out of sight of the clubhouse, and play real golf with his 3-iron, another excellent exercise for the beginner.

Above all, he reveled in his youthful strength and he liked to belt the ball as hard as he could. Why not? Youth is the time for flexing the muscles. That is what they are for. Besides, there was nobody there to preach the doctrine of three-quarter power. He hit flat out and gloried in his strength.

As for tactics, he applied the simple pragmatism of youth. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line so why not aim directly at the flag every time? If trees intervene, then you just fly the ball over the tops of them. Bunkers? Why worry about them? After all the hours he had spent on the beach Ballesteros knew how to control the ball from every type of sand, dry or damp. The Ballesteros philosophy of golf, uninfluenced by instruction books or the received wisdom of cautious elders, was born at the Pedreña course during those early teenage years. The elder Ballesteros brothers gave Severiano advice, help and encouragement when he asked for it but the youngster's stubbornness forced him to work out his problems for himself for the most part.

The one day of the year when the caddies were allowed to play Real Pedreña was for the caddies championship. Ballesteros won it at the age of 14, in such promising style that he was granted special privileges to play the course in the evenings. The next year he repeated his victory, with a score of level par, and he felt he was ready to take the world of pro golf by storm.

He traveled to Lisbon to try to qualify for the Portuguese Open, the first journey he had made away from home. He just managed to break 90 and returned to Santander embarrassed and disappointed but no whit discouraged. Next time would be better. So it was. Ballesteros learned by his experience and practiced like a demon.

The Spanish professionals tend to travel as a clan on the European Circuit, as do the other national groupings, naturally enough, sharing the same hotels and making up practice foursomes among themselves. It was at this time that Angel Gallardo, the father figure of the Spanish contingent, said to me: "Come out and watch Manolo's brother. The kid is fantastic."

As I recall, the Ballesteros brothers were playing Jose-Maria Canizares and Francisco Abreu the ex-wrestler who bombs the ball a mile. Severiano was hitting it far past Abreu but he was wild, awfully wild. What impressed me more was the uncanny way he had of getting the ball up and down from the unlikeliest places. Everyone who saw the Ballesteros boy play, in those days marked him down as something special. None of us, I think, realized how special he was to become.

The first real indication of that came in 1976 when Ballesteros, a victim of his impetuosity, made a hash of the 12th and 13th holes in the last round of the British Open at Royal Birkdaleand then came back with a rush of birdies to finish a close second to Johnny Miller. A teenage kid ought to be thrilled to finish second in a great championship. Not Ballesteros. He was disgusted with himself and insisted that he could, and should, have won .

It was not long before he was on the winning trail. He took the Dutch Open for his first major victory, although he had already collected some domestic Spanish titles. And then in partnership with Manuel Pinero, the tiny genius of Spanish golf, he brought home the World Cup to Spain.

By and large, Spain was not impressed. It burned Ballesteros that while he was becoming a popular hero in Britain, his own countrymen took no notice of his triumphs. He rated a line or two in the papers, if that. He now showed another side of his character. a tendency to pursue grudges and elevate them to crusades.

Dean Beaman was to run up against this streak of Ballesteros' personality when the tour rules were bent to offer the youngster a player's card without the formality of graduating through the qualifying school. Foreign players on the PGA Tour are allowed automatic releases from American tournaments to play whenever they like on their home circuits. Beaman ruled that Ballesteros' home circuit was Spain. No, insisted Ballesteros, his home circuit was Europe and unless Beman accepted that interpretation he could keep his card. That remains a sticky point between them and it is the reason Ballesteros does not play more often in America.

He has a reputation for being anti-American but that is not the case. He admires much about American golf and respects the better players without being in the least bit in awe of them. He certainly will play more in America in the future, when his English improves and he becomes accustomed to the alien atmosphere -- but he will do so only on his own terms and in his own good time.

He also has another grudge to work out of his system. When he won the British Open at Lytham last year, hitting only 14 fairways in four rounds and making that famous birdie from a car park, he was tagged "Lucky" Ballesteros. Winning the Masters in April was his response. He will be throwing that "Lucky" label back into the teeth of his accusers for years to come and it will also spur him on to more victories.

Have I painted him in too somber colors, presenting him as a hard, obsessive fanatic? If so, I have done him an injustice, because there is a warm and sunny side to Ballesteros. He is excellent company when he unwinds, with a sharp, satirical sense of humor that he is quite willing to turn against himself. Like Nicklaus, he points himself for certain tournaments and on those occasions his dedication and ambition turn to a frightening intensity.

This fanaticism caused him to injure his back through excessive practice of that ferocious swing and it was probably his withdrawal into a cocoon of concentration that caused him to commit that absurd error of mistaking his starting time and being disqualified from this year's U.S. Open at Baltusrol. But because he is so mature -- he seems to have been born with the mind of a grown man -- it is easy to forget that he is only 23 and still developing. He has changed during his meteoric career. The Ballesteros of today is not nearly so concerned with money as he was when he first saw golf as a release from poverty, and now his goals concern achievement rather than materialism. He accepts a responsibility to support lesser tournaments as well as the rich ones and lately he has developed a facility to tailor his game to suit the special conditions of the course he is playing, rather than seeking to overwhelm every course with his slam-bang tactics. His back injury may have been a blessing in disguise because it faced him to rethink his views about the game and now, with that problem out of the way, he has emerged as a much better player.

As to such questions of whether he is today the best golfer in the world, or whether he can challenge the records of Nicklaus, there can be no absolute answers. My own belief is that within two years he will put that first question beyond argument by even the most ardent supporter of Tom Watson or anyone else. The second question must remain the subject of speculation but, compared with Nicklaus' progress at the same age, he is well on course. If he retains his fanatical ambition, then who can say he will not do it?