News

Risk, Reward, & Retching

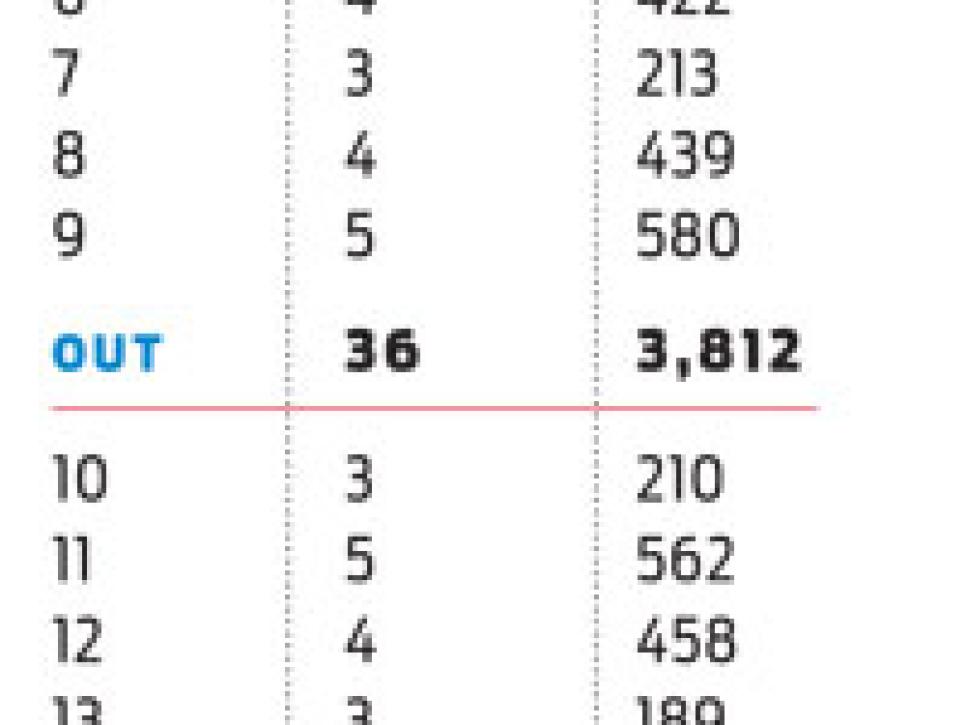

The serene scene in Wales will come alive starting Oct. 1 when Europe gets the home field at Celtic Manor for the Ryder Cup matches. Take a tour of Celtic Manor with hole-by-hole photos and video flyovers.

In the all-to-often cliché-ridden language of professional golf, there are apparently three levels of pressure: tournament pressure, major-championship pressure and, above all others, Ryder Cup pressure. The biennial matches between the United States and Europe offer nothing in the way of prize money; the players compete for national pride.

There is evidence aplenty that patriotism is more than enough to affect even the sturdiest competitors. Mark Calcavecchia, the 1989 British Open champion, was reduced to a blubbering wreck wandering aimlessly on a beach after losing the last four holes to halve his singles match against Colin Montgomerie at Kiawah Island in 1991. Fred Couples, the 1992 Masters winner, missed the 18th green at The Belfry by as much as 40 yards with only a 9-iron in his hands in 1989. And no one who watched Irishman Philip Walton literally stagger onto the last green at Oak Hill in 1995 thought he was in any state to continue even one more hole.

So match play does funny things to golfers, even special golfers. To the professional practitioner, match-play golf has forever been labeled "a different game." Decoded, that thinly disguised euphemism makes clear two things: A pampered preference for the week-to-week discipline of adding up shots in stroke play, and an inherent distaste for a form of competition designed to produce winners and losers rather than a large number of highly paid nonwinners. Unable to hide behind the invariably lucrative "success" that is the tie for eighth, the pro golfer is forced to admit that second place in match play makes him "a loser."

The best matches need the right environment. A mix of holes is required, everything from tough to easy, with those that bring a large number of scores into play the most enthralling. This year, Celtic Manor's Twenty Ten Course, though no one's idea of the perfect venue, offers in places -- and especially toward the end -- the strategic choices that make match play golf's most exciting format. (That goes for amateurs as well as pros.

)

"The whole course is very well-suited to match play," says Rhys Davies, the only Welshman with a reasonable expectation of making the European team, which will try to reclaim the Cup after the United States' 16½-11½ victory two years ago at Valhalla halted three consecutive losses and put the Americans' all-time advantage at 25-10-2. "When we played there earlier this year [the European tour's Celtic Manor Wales Open, won with a 64-63 finish by Graeme McDowell, who would become the U.S. Open champion two weeks later], they had a few pins tucked behind bunkers, so we had to play away from them a bit to be sensible. But in match play you can be a lot more aggressive. It's very much a birdie/bogey-style course -- which is what you want in match play. Right from the start that's true. You can get off to a flier or be 2 down before you know it."

No. 15: the par 4 can be drivable, but water awaits near the green.

Still, it is over the closing holes that Ryder Cup points are really going to be won and lost.

"The last five holes provide a good mix," says course architect Ross McMurray. "There are three definite gambling opportunities and two holes where -- assuming the prevailing wind -- par is hardly ever going to be a bad score. It's all about balance, though. During the design process I was aware that we had to provide drama and chances for the players to go for it. But it has to be challenging, too. I didn't want to build a course where someone is likely to finish with four birdies and an eagle. It has to be tougher than that."

Though the last five holes will provide the ideal platform for games to swing back and forth, a couple of the earlier holes will also give the player so inclined plenty of temptation. As Davies intimated, as early as the 433-yard fifth hole, choices are there to be made.

"I love this hole," McMurray says. "It can be played as a longish par 4 from the back tee or, because the green is best approached from the right side, as a much shorter two-shotter where the players are encouraged to drive into the sliver of fairway on that side. I wanted to give aggressiveness its due -- classic risk-reward stuff -- without it being too contrived. The fifth does that nicely, I think."

Of course, no matches are going to be decided as early as the fifth hole, even if it is the type of hole match play is made for. "The short par-4 10th at The Belfry is a great match-play hole," McMurray says, "but it comes too soon in the round to be in any way decisive."

The same cannot be said of the 377-yard 15th (below, left). Just as its counterpart at The Belfry has been over the years, it's likely that this drivable par 4 will be the most memorable hole during the Ryder Cup. Cutting across the sharp left-to-right dogleg, the adventurous player brings the putting surface within range, as well as a multitude of thick rough beyond and to the right and a water hazard to the left.

"The 15th is always drivable," says 1999 British Open champion Paul Lawrie, who won the Celtic Manor Wales Open in 2002. "But there is so much danger lurking. From the tee they used in the Wales Open this year, it was 270 yards to the front of the green. I hit a 3-wood pin-high. From the back tee -- which is a little more to the left -- it's a better hole. You have to hit driver from there. But even then you can pitch the ball on the green. And when that is the case, the vast majority of players will have a go."

The next two holes offer more prosaic challenges where, into the prevailing breeze, pars are unlikely to lose holes.

"It's like you shouldn't be winning the 15th or 18th with birdies, but you shouldn't be losing 16 or 17 with pars," Lawrie says. "That's a nice mixture."

The 18th, a downhill, 575-yard par 5 with a steep slope and water in front of the green, has the potential to provide the sort of climax so beloved by Ryder Cup spectators -- and dreaded by players. There is only one proviso: The green must be reachable in two shots. Otherwise, like all three-shot par 5s at the professional level, the hole becomes merely a 100-yard par 3, one that is relatively boring for players and galleries.

"I'm sure the 18th tee will be wherever it needs to be for players to reach in two," Davies says. "If it's out of range, it gets a bit dull. But when the green is in range, all you have to do is stick the pin in the middle at the front. That brings the slope and the water into play and makes it very exciting." Lawrie doesn't want it to be too easy, though.

"I'd like to see the last reachable, but only with two really good woods," he says. "If you can reach with an iron, the hole loses some of its impact."

Whatever the outcome of Wales' first Ryder Cup, one thing is for sure (cue yet another cliché): Match-play golf will be the real winner.