This was about 10 years ago, during the Masters. It was early in the week, and I was standing under Augusta National’s famous tree talking to a number of people, watching the elite of the golf world—players, TV stars, agents, big-shot officials—walking to and from the clubhouse. For some reason, my eye caught sight of an older man standing outside the ropes, waving his arms as if trying to get someone’s attention—anyone’s attention. He was dressed garishly, stripes going in different directions, bright-yellow pants.

“Who is that?” I remember saying.

I believe it was my friend and colleague Dave Kindred who answered—although Kindred wasn’t certain when I checked with him on Monday to see if my memory was correct.

“That’s Doug Sanders,” Kindred—or someone in our group—said.

I looked more closely. It was Doug Sanders. I was stunned. “You mean Doug Sanders doesn’t have a credential to get inside the ropes here?” I said. “Doug Sanders? Really?”

Really.

Doug Sanders, who died on Sunday at age 86, won 20 times on the PGA Tour. On four occasions, he finished second in major championships—losing three times by one shot and, most famously, losing to Jack Nicklaus in a playoff at St. Andrews in the 1970 Open Championship. On the 72nd hole, needing a par to win, Sanders pushed a 30-inch putt that allowed Nicklaus to tie him. “They still ask me if I ever think about that putt I missed to win the 1970 Open at St. Andrews,” he said years later. “I tell them sometimes it doesn’t cross my mind for a full five minutes.”

He also said: “If I was a master of the English language, I don’t think I could find the adjectives to describe how I felt when I missed that short putt.”

If Sanders had made that putt, there’s no doubt in my mind he’d be in the World Golf Hall of Fame. How could he not be? His record—21 wins plus that missing major—would be far more impressive than many in the Hall.

R&A Championships

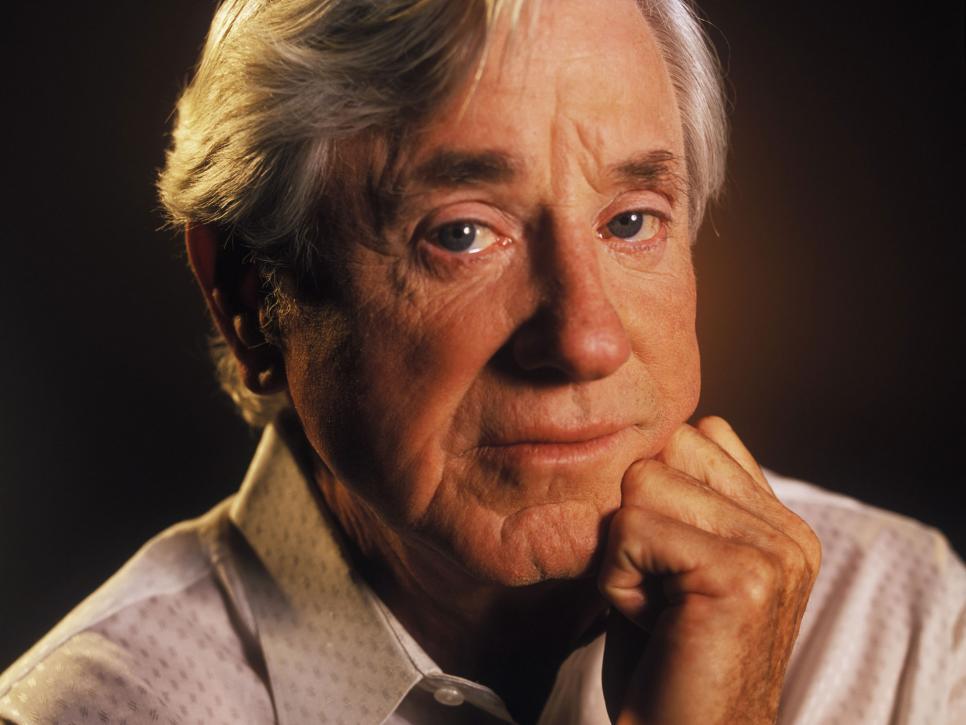

The buttoned-up world of golf didn’t like the way he dressed—his nickname was “the peacock of the fairways.” People didn’t like his lifestyle—Sanders was never shy about how much he enjoyed partying. And they didn’t like his bluntness. Ask him a question, he answered it.

I was always fascinated by Sanders—dating to 1966, when I was just starting to watch golf and I saw him beat Arnold Palmer in a playoff to win the Bob Hope Desert Classic. Palmer was my favorite player, but it was impossible not to notice Sanders because of his golf swing, which was once described as being so short he could swing in a phone booth. Then there were his clothes and the fact that he could flat out play.

Ten years after I watched that Bob Hope playoff—six years after St. Andrews—Sanders was the first golfer I ever interviewed. I was a college junior, and in those days, the Greater Greensboro Open would send credential forms to student newspapers around the state of North Carolina. I filled one out and showed up for Saturday’s third round at Sedgefield Country Club.

I wanted to write two stories: One on what it felt like to be at a professional golf tournament for the first time, the second on Doug Sanders—if he’d talk to me.

I walked the back nine with Sanders and, after he signed his scorecard, I nervously walked up and introduced myself.

“Student newspaper at Duke, huh?” he said. Then, before I could think of a clever response, he said, “Come on inside. I’ll buy you a beer and we’ll talk.”

And so, we did. I illegally sat at the bar (I was 19) with Sanders, and he regaled me with stories for a solid hour. When I told him I was sure he was sick of being asked about St. Andrews, he laughed and said, “Not nearly as sick as I get when I think about missing that putt.”

I spent an hour with Sanders that day and had enough material for three columns. He explained to me that his phone-booth swing had come about because of a neck injury that made a fuller swing impossible. My only complaint was, after the time in the bar I had to hang around the media room for an extra hour before I dared get behind the wheel of a car.

Sanders’ first win on the PGA Tour was at the 1956 Canadian Open—while he was still an amateur. It wasn’t until 29 years later, when Scott Verplank won the Western Open, that another amateur won on tour.

Sanders went head-to-head with some of golf’s all-time greats throughout his career. In addition to losing the playoff to Nicklaus by one stroke at St. Andrews, he lost to him by one in 1966—also at St. Andrews. He lost an 18-hole playoff to Palmer at Phoenix in 1961 before beating him five years later at the Hope. He lost to Julius Boros in a playoff at Greensboro in 1964 and beat Nicklaus in a playoff a year later at Pensacola. His last tour victory was the 1972 Kemper Open—by one shot over Lee Trevino.

Sanders played on Ben Hogan’s 1967 Ryder Cup team—the one introduced by Hogan as “the 12 greatest golfers in the world.” The Americans won those matches, 23½-8½, which remains the widest margin of victory in Ryder Cup history.

Darren Carroll/Getty Images

That day at Augusta, Kindred walked outside the ropes to talk to Sanders. They found a place to sit and talked for a while.

“All I remember is feeling badly for him,” Kindred said on Monday. “It wasn’t that he was dressed so garishly, he was just kind of a mess. I remember him saying something about if he could have made one birdie, four pars and a bogey at specific holes, he would have won five majors, including the Grand Slam. It was all kind of sad.”

Sanders clearly had many great moments in his life. In 2007, he told Golf Digest that at the peak of his career, “The two questions asked most on tour were, ‘What did Arnold Palmer shoot, and what is Doug Sanders wearing?’ ”

He claimed once to own more than 350 pairs of shoes and clearly had many memorable moments—on and off the golf course.

But when I heard that he’d died, I felt sad, much like Kindred at Augusta. Two memories came quickly: the outgoing, generous man buying beers and filling the notebook of a kid reporter, and the older man trying desperately to get someone’s attention while on the outside looking in at the Masters.

I would say that Sanders did more in golf than about 90 percent of us who had inside-the-ropes access that day. Maybe he was eccentric—OK, clearly he was eccentric—and perhaps he didn’t make a lot of friends in the game through the years. But he was an outstanding player who also brought a lot of attention to the game because of his unique style and willingness to share honest feelings with the media.

Some people are more comfortable with guys who make sure to thank the sponsors and the volunteers and who are willing to break down their birdies and bogeys in detail. I’ll take Sanders, especially since I still owe him a beer. Several, in fact.