Putt-Putt: The Other U.S. Open

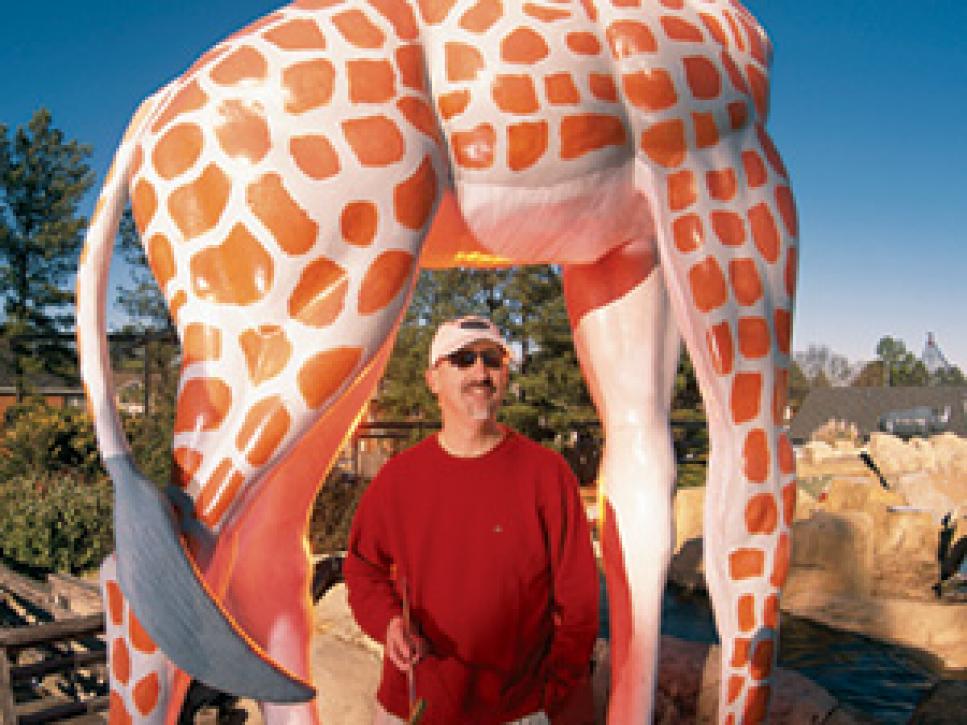

Greg Ward is a true giant in the world of putting, standing head and shoulders above the rest.

Four miles from the gates of Augusta National Golf Club, out past the many splendored fast-food temples and religious emporiums, beyond the off-brand video parlors, the Skate Red Wing Rollerway ("Christian Nite on Tuesday!") and the Wife Saver Chicken Sea Food restaurant, on the other side of the tracks of the freight line that runs to Atlanta, lies a collection of the scariest putting surfaces in town.

We are gathered here today for the 43rd annual National Championships of Putt-Putt, a serious endeavor -- not to be confused with miniature golf -- but one that nevertheless is to sport what the kazoo is to music, what holding hands is to sex. It's August in Augusta, the dog days of summer. The azaleas have long since wilted, the National is shuttered until October, and Tiger and the tour are in another town, far away.

At the Putt-Putt Golf & Games facility, where major champions like Mark Calcavecchia, Lee Janzen and Scott Simpson have come to putt during Masters week, the atmosphere is electric. At 10 a.m., a crackly national anthem is played over the loudspeakers. A huge, bemused fiberglass giraffe looks down on the proceedings from a fake rock outcropping in the middle of the course. The official starter, sitting behind a counter surrounded by racks of putters and candy-colored golf balls, leans in to the microphone and announces the first group onto the tee.

The defending champion steps up to the first hole of the Red Course and meticulously places his ball in just the right spot on the little green plastic square that constitutes a Putt-Putt tee. It is perfectly quiet as he wipes away an imaginary impediment in front of him, hunches over the ball, takes a series of tiny practice swings, and hitches up the back of his pants. Then he strikes the ball, and it silently rolls over the synthetic green carpet, traverses a hump and falls tidily into the center of the hole. The game has begun, this tournament that everyone refers to as "our Masters" but is really Putt-Putt's U.S. Open, amateur, junior and senior all rolled into one.

The defending champion is Greg Ward. He would never say such a thing, given his modesty, but he might be the greatest putter who ever lived.

FIRST STOP: LYNCHBURG

The road to Augusta began for me three months earlier, on a warm Tuesday night in Lynchburg, Va. Because I wasn't a Putt-Putt pro, I had only one avenue to play in the Nationals -- join the Amateur Putters Association. To do that, you have to play in a local tournament and be recommended for membership by a Putt-Putt course owner. The owner of the Lynchburg Putt-Putt, Joe Aboid, happens also to be the commissioner of the sport, so I had come to the right place.

"All kinds of people play the game," said Joe, who was grappling with a malfunctioning machine in the video-game room when I met him. "You can play with grandmothers and grandchildren, you don't have to be able to hit the ball 300 yards. It really gives me a thrill to see families come out and all have fun together."

Joe's father, a Putt-Putt Hall of Famer and the son of a Lebanese cobbler, built the first ever Putt-Putt in Cleveland, in 1960, and Joe soon entered the family business. In the heart of the Bible Belt, he is a full-time Putt-Putt evangelist.

He gave me a Strata Tour Ultimate -- the official ball of Putt-Putt -- then I paid my $7 entry fee and headed toward the first hole of the tournament course, where I met a fellow named Ron who showed me the ropes over a couple of practice rounds. Local knowledge is a big part of this game. Ron explained how heat, moisture, wind and even time of day can affect the way the ball rolls. He would say things like: "This hole we use the No. 3 tee spot, bank it off the left rail, front door."

We played with a retiree named Gene, who took up the game four years ago, has 104 trophies to his name, and was dressed in denim shorts, sneakers and a baseball cap sporting the logo of a mobile-home dealership.

There were kids playing with their parents, older kids playing with their dates, students from nearby Liberty University, middle-aged middle managers, an accountant, a janitor, a painter, a guy who works for the Ramada Inn, retirees, some fuzzy-haired ladies -- the whole carnival of humankind was on parade beneath the neon lights of the nearby Dairy Queen on Timberlake Road, utterly engrossed in the wholesome, sweetly innocent act of putting. Popular hits from long ago lost summer afternoons hung in the air like a warm mist.

It was when we were on the third hole in the second round that the proceedings were interrupted by the arrival of a big black SUV, honking its horn. A big man in a big black suit stepped out. It was the Reverend Jerry Falwell.

Falwell's house is just down the road, as is Liberty University, which he founded. He had stopped by to see his son and some of his grandchildren, who were playing on one of the other courses. It turned out that Ron, whose family is in the Christian music business, knows him. In fact, everyone seemed to know him. "He's been great to me," said Ron. "He took me on his private jet to meet President Bush once. It was the highlight of my life, I would say."

Falwell was waiting for us as we played the 18th. "Watch Ron," he joked. "He's known for making up his score."

I asked Falwell if he was a golfer, but he said he doesn't even have time to do Putt-Putt. He was wearing a "Jesus First" lapel pin.

"But he does bungee jump," offered Ron. "He did it once wearing a black suit. He's not afraid of anything."

The Reverend laughed, gave me a playful jab in the stomach, then wandered off, strolling around the Putt-Putt, tending to his flock.

There are many mental images that can prove beneficial to the tender, fragile art of putting -- the ebb and flow of the waves, for instance, or the swinging of a pendulum. Jerry Falwell bungee jumping in a black suit, alas, is not one those images. After my first round of 30, six under par, I had stood in third place, but following this strange, unsettling encounter, it was as if my bottle of Gatorade had turned into a poisoned chalice: The stroke was lost, a run of bad holes ensued, and the tournament ended for me with a disastrous, dreaded four-putt. I finished nowhere.

All was not lost, however. Joe told me I had not disgraced myself, and he agreed to recommend me for membership to the Amateur Putters Association. I was going to the Nationals! I suddenly felt a great kinship with my fellow Putt-Putters and promptly chatted up one of the fuzzy-haired older ladies. Her name was Dorothy, and she'd scored a respectable 94 -- 11 strokes better than I did -- but she wasn't satisfied. "I normally do better than that," she said. "But I was nervous tonight. There were too many people here."

The runaway winner was Dave Gallier, a 19-year-old student with a linebacker's build and the touch of a brain surgeon, who shot three 27s for his first victory. There was a brief prize-giving ceremony and then, of course, it was back to ... more putting.

It's an addictive game. An empty first tee holds out the promise of perfection and is impossible to ignore. "It doesn't matter if you're Tiger Woods or a little kid," one player told me, "there's a universal appeal to a ball falling into the cup." Putt-Putt is a world in miniature, an endless series of tiny challenges and obstacles that can be overcome if you approach them in just the right way, with the right concentration, luck and skill. It is life reduced to manageable proportions, a small world that makes you bigger.

THE MADNESS SWEEPS AMERICA

Putt-Putt began 50 years ago because a 28-year-old salesman in Fayetteville, N.C., had a nervous breakdown. Don Clayton was tall, handsome and charming, an outstanding athlete, a good golfer and one of the top insurance agents in the country. But sometimes, driving in his car, for no good reason he would start crying.

His doctor prescribed 30 days of complete rest. But instead, Clayton became obsessed with the idea of miniature golf. He would spend hours designing tiny golf holes on index cards, then he'd lay them out on his living room floor with string. He bought some land on the busiest intersection in Fayetteville and opened the first Putt-Putt course there in June 1954. It was an immediate success. There wasn't much else to do in small-town America back then. He opened another course. Then another. And pretty soon, in the same era that saw the emergence of Holiday Inn, Howard Johnson, McDonald's, Kentucky Fried Chicken and other roadside attractions, the Putt-Putt franchise that would bestow millions upon the charismatic Clayton was born.

Miniature golf itself was nothing new. The first such course was built in 1916, on a private estate in Pinehurst, N.C. Soon they were springing up everywhere. By 1930 there were 150 rooftop putting courses in Manhattan alone, and perhaps 50,000 miniature golf courses nationwide.

Miniature golf came to be known as The Madness of 1930. Courses appeared in the basements of hotels, in the exercise yards of prisons, on the decks of ocean liners. Instruction books and magazines were published. A record -- "I've Gone Goofy Over Miniature Golf" -- was released. The New York Times wrote that miniature golf "gave some indication of replacing movies as the nation's fifth-largest industry," something that caused terrified Hollywood studio executives to order their stars to stay off the little links. Most defied the ban: Fred Astaire, an avid golfer, was photographed putting on the roof of the Hotel White in New York, Fay Wray was seen playing in Los Angeles, and Mary Pickford even opened her own course -- the first night brought traffic to a standstill as she and Douglas Fairbanks took on all comers.

The Marines were called in to build a course at President Hoover's summer camp in Maryland. The Prince of Wales demanded a course at St. James' Palace in London. The game was played by the rich and famous, but by ordinary working folk, too -- it was an inexpensive and enjoyable escape from the gathering economic storm clouds. (Of course, it was not a completely democratic idyll: There were courses for "coloreds only," and The Los Angeles Times reported that putting seemed to come naturally to women on account of their "hereditary gift of wielding a broom day in and day out.")

The elfin courses went to great lengths to outdo their competitors. Glamorous ladies were hired to entice passersby, as were circus animals, live bands and singing midgets. Marathon dancing, pole-sitting, pie-eating and mini-golf contests were held. The themes for individual courses became ever more ingenious and fantastic: There were sunken gardens, light shows, waterfalls; courses depicting the Wild West, the South American jungle, the grand palaces of Europe, the Great Wall of China. Miniature golf courses were the nation's first theme parks.

Millions took to the game. Courses would stay open until 4 a.m., and tipsy revelers in ball gowns and dinner jackets would stop by for a quick round before heading for home -- the perfect end to a long night out. In the vernacular of the times, miniature golf was truly gay.

It was a classic bubble. Inexorably, it burst. The nation was saturated with courses, which increasingly were facing legal restrictions, and with a galloping Great Depression, suddenly the game didn't seem so funny anymore. America's favorite cowboy, Will Rogers, summed up the new zeitgeist: "There's millions got a putter in their hand when they ought to have a shovel."

By the time Don Clayton quit the insurance business, the blossoming postwar suburbs had given rise to a modest renaissance of the game (George W. and Laura Bush had their first date on a miniature golf course in Midland, Tex.). But Clayton hated all the wacky gimmicks associated with most miniature golf courses. He wanted his courses to be a true test of skill, not luck. He personally designed and copyrighted every Putt-Putt hole -- they are all par 2, and all are devoid of clowns' mouths or windmills or other whimsical distractions (the giant safari animals at Putt-Putt courses are merely set decoration). Clayton made sure every detail of every franchise was just right. He persuaded Sam Snead to play Putt-Putt, and he got TV interested too -- the Putt-Putt Parade of Champions on Sundays became one of the longest-running sports shows in history. At the top of Clayton's game, there were more than 250 franchises in 10 countries. He died in 1996, but his persona still looms large. As one old-time Putt-Putter told me, "He could sell fleas to a dog."

Now, thanks to land costs, computers and interstates, Putt-Putt has declined. There are only about 170 courses left, there's no TV coverage anymore, and Putt-Putt World magazine recently disappeared after publishing for 42 years.

Miniature golf, meanwhile, has continued to grow. It is looked upon with disdain by Putt-Putters as a frivolous game of chance, not skill, but there are thousands of imaginative courses across America, like the Hawaiian Rumble in North Myrtle Beach, the Pebble Beach of putting, whose centerpiece is an erupting volcano. Putt-Putt's rival, the U.S. ProMiniGolf Association, sanctions its own tournaments, and there are international events, too, frequented by squads of peculiar Europeans who travel with swing gurus and mental coaches, plus an enormous variety of balls of different spin and bounce and firmness, all stored in mini humidors to keep them at optimum temperatures. Miniature golf has even been accepted by the International Olympic Committee as a provisional sport for the 2007 World Games, a feeder for the Olympics. (Synchronized swimming suddenly seems almost sensible.) The future of miniature golf -- and Putt-Putt -- remains to be seen, but the days of The Madness are long gone, and nothing whose defining characteristic is smallness is likely to make it big in modern America.

BAND OF BROTHERS

The most remarkable thing about Greg Ward is that he is completely unremarkable. He lives in the suburbs. Works in sales for a construction company. Father. Middle-aged. Occasional golfer. A man for all seasons. Everyone's friend. Hell of a guy.

But Ward's secret is that he can really, really putt. The Putter of the Decade for the 1990s has won 145 state and national Putt-Putt titles, more than anyone else in history.

"I really love playing," he had said when we first met a few months earlier in a steakhouse off I-20 outside Atlanta. "It's a great outlet for my competitive urges. And you meet so many really nice folks, great people."

Putt-Putt is like golf's pro tour used to be decades ago, a merry band of colorful, slightly loopy characters who travel together by car to cheap motels in one-horse towns, squeezing the game into the oddly shaped crevices between their jobs and their families for the simple reason that they love it. (It's certainly not about the money: For all Ward's brilliance, his career earnings are just $135,000, about what you'd get for a 10th-place finish in a crummy PGA Tour event.)

Putt-Putt is guys like John Napoli, the only man alive to have scored a perfect 18 -- he can still recall how nervous he was on the 18th hole that windless Wednesday evening in Ohio in 1979, how he hit the ball too hard, and how it dived into the cup anyway. Guys like Adam Sahmel, a senior at the University of Texas for whom a round of Putt-Putt is a true obstacle course requiring unimaginable effort and courage because he has cerebral palsy -- he is the No. 2-ranked amateur Putt-Putter in Texas. Guys like Al Simpson, the official starter, who ran a Putt-Putt in Louisiana for three decades until it was bulldozed to make way for a bank -- he hasn't slowed down any despite having a device under his skin to kick-start his heart whenever it stops. "If you're going to go," he says, "you might as well go doing what you want to do."

Or guys like Vance Randall, a tall, Hollywood-looking fellow with gunslinger eyes and an Errol Flynn mustache, Putt-Putt's first superstar. In 1979 he played 50 exhibition matches all over the U.S., and 20 in Japan, too. "They really rolled out the red carpet for me," says Randall, a lifelong scratch golfer who tried to play the Senior PGA Tour when he turned 50. "I played in Japan's national Putt-Putt championship, and there were billboards all over town about it. And I won it. They put me up on a podium, like in the Olympics. It was unreal."

Randall was a key figure in a notorious challenge match between Putt-Putt and the PGA in 1964. Five tour pros -- Dave Hill, Don Massengale, Lou Graham, Rex Baxter and Randy Glover -- took on five Putt-Putt pros in Florida: 36 holes of Putt-Putt one day, 36 holes of putting on grass the next. The Putt-Putters helped the tour pros on day one, showing them the line and pace on each hole. "Then the next day, they didn't show us nothing on them greens," says Randall. "They had us hitting putts that were 50 to 75 yards, and the grass had been shaved all the way down. But it was still close. It was our mistake -- we shouldn't have helped them."

Randall invented a highly individual putting style, much copied by Putt-Putters: You choke way down on the grip and play the ball inches off your left big toe, with the right foot pulled all the way back. "The main thing is consistency," says Randall, who also claims to have invented bleachers at golf tournaments. "If the ball is always just off your left foot, there's no variation at all in your ball position. Ever."

He first got into the game in college, when he had a job moonlighting as manager of a Putt-Putt course in Asheville, N.C. "I'd play with my buddies," says Randall. "And I'd keep that course open and we'd play all night long." Many's the time they'd still be putting when a new day dawned, oblivious to the rising sun.

THE HOME STRETCH

Greg Ward was holing everything at the Nationals. He opened the defense of his title with 14 aces in the first 16 holes. My own putt-ing, however, was less impressive. I came to grief early on, at the triple-tiered "wedding cake" hole: An initial effort didn't have enough steam to climb the second tier, and it rolled back pitifully toward me, over the tee, down some concrete steps and into a nearby flower bed, a situation requiring an emergency ruling.

It was hard to concentrate. It was hot, and the pace of play was deadly. The pro competitors, some of whom had been here practicing for a month, were taking the event very seriously, and could be seen actually backing away from putts, or hurling their putters to the floor in disgust, or pumping their fists in triumph. All the mannerisms that you might see at the real Masters were on display.

There were not many other similarities, however. The Augusta National clubhouse, for instance, does not offer skee ball, Austin Powers Pinball or a choice of four Daytona USA Sega machines. Buddy Holly is never broadcast across Amen Corner.

Then there's the dizzying variety of strange Putt-Putt putting styles. There was a man who putted bent over double, squatting over the ball with his elbows fully splayed; another whose putter had a thick, blue toweling grip that he held at the very end, with both hands wrapped around each other like a double fist; yet another who putted croquet style, between his legs, with an implement that looked like it might be better suited to planting potatoes.

For the final day of the amateur competition, I was paired with 13-year-old Brittany Davis, granddaughter of another putting legend, Augusta native Tracy Moore, who was dying from lung cancer when he won the 1965 National Championship -- within a year he was buried in his favorite black Putt-Putt shirt. I had a better day, even managing a couple of nine-under-par rounds of 27, but at the Nationals nine under is only average. I finished 38th out of 44 amateurs, 48 shots behind the winner.

When you spend hours a day for days on end doing nothing but putting, you realize how bad you are at it. All these years, you've just been playing at it, shoving the ball toward the hole and hoping for the best with no clue as to what you're doing. After a while, you slip into a meditative putting trance: It's extraordinary how comfortable you can get over the ball, how smooth and grooved and precise your stroke becomes, how pure the impact with the ball gets -- it even sounds different. There's so much we don't bother to practice, or do well, content instead to slide through life taking mediocrity for granted.

Ward, meanwhile, had slid effortlessly into the lead on day two, averaging 13 under per round, but come Sunday, he found his highly tuned engine to be, in his own words, "just a little bit off." Cliff Matthews, a 28-year-old croupier and self-confessed gambler who had driven 14 hours from Dallas to get to the Nationals, pushed ahead in round 11, and stayed there in round 12. Ward beat his previous year's record -- 120 under for 12 rounds -- by 16 shots. But Matthews beat it by 20. The phenomenal scoring was the talk of the town.

In an impromptu press conference with two members of the press, Matthews explained his unusual transition to cross-handed putting: He plays golf left-handed, to a 10-handicap, and in the early '90s, attempting to cure the yips, he decided to start putting right-handed. But he didn't bother to change the position of his hands on the club. Whatever he did, it seems to have worked. For Matthews, the victory was the reward for a lot of hard work: He had spent 10 hours a day practicing at the Putt-Putt for 10 straight days.

There was no green-jacket ceremony. First prize was $2,500. The assembled gathering could have fit comfortably inside one medium-size bus. But everyone was happy, even the defeated Ward, a consummate sportsman.

At the airport I ran into a Putt-Putter called Rich Gilooly, on his way home to Amsterdam, taking his beloved putter as carry-on luggage in a black canvas holster. He comes back every year for the tournament, and to catch up with friends, and if time permits to call in on his brother, a Putt-Putt owner in Newark, Ohio. "If you go to the mall with him, he knows everyone," says Gilooly. "All because of Putt-Putt. He could run for mayor."

I had sat next to Gilooly a few days earlier, the night before the tournament, when the entire Putt-Putt community had crammed into the Partridge Inn in downtown Augusta for the annual Hall of Fame banquet. Greg Ward was an inductee. The discussion at our table centered on the tournament's mandatory and controversial long-pants policy, fondly remembered Putt-Putts ("How about that sidehill hole in Ypsilanti?"), and what a swell guy Greg Ward is.

Ward was given so many cups and awards that his 9-year-old daughter, Kaitlynne, had to squeeze her way through the tables to the podium to help him carry them all.

In his brief acceptance speech, he summed up what the sport means to him: "The people I've met and the friendships I've made through Putt-Putt," said Ward. "That, for me, is the whole deal."