Masters 2024

Phil Mickelson's greatest triumph came 20 years ago. He and golf haven't been the same since

Cast your mind back 20 years, which at the moment in golf might seem like 200, and imagine Phil Mickelson in April 2004.

Hall of Fame bound with 22 PGA Tour victories at the prime age of 33. A long, loose left-handed swing whose daring could be justified by the game’s ultimate mistake eraser, the Phil Phlop, as majestic and singular as Kareem’s Sky Hook. A showman who won the crowd with a shy grin his father, Phil Sr., called “the mark of a really fine human being.” A buoyant competitor who unleashed a performative arrogance in practice-round money games, filling the space between audacious shots with know-it-all monologues that entertained while establishing alpha-dog cred.

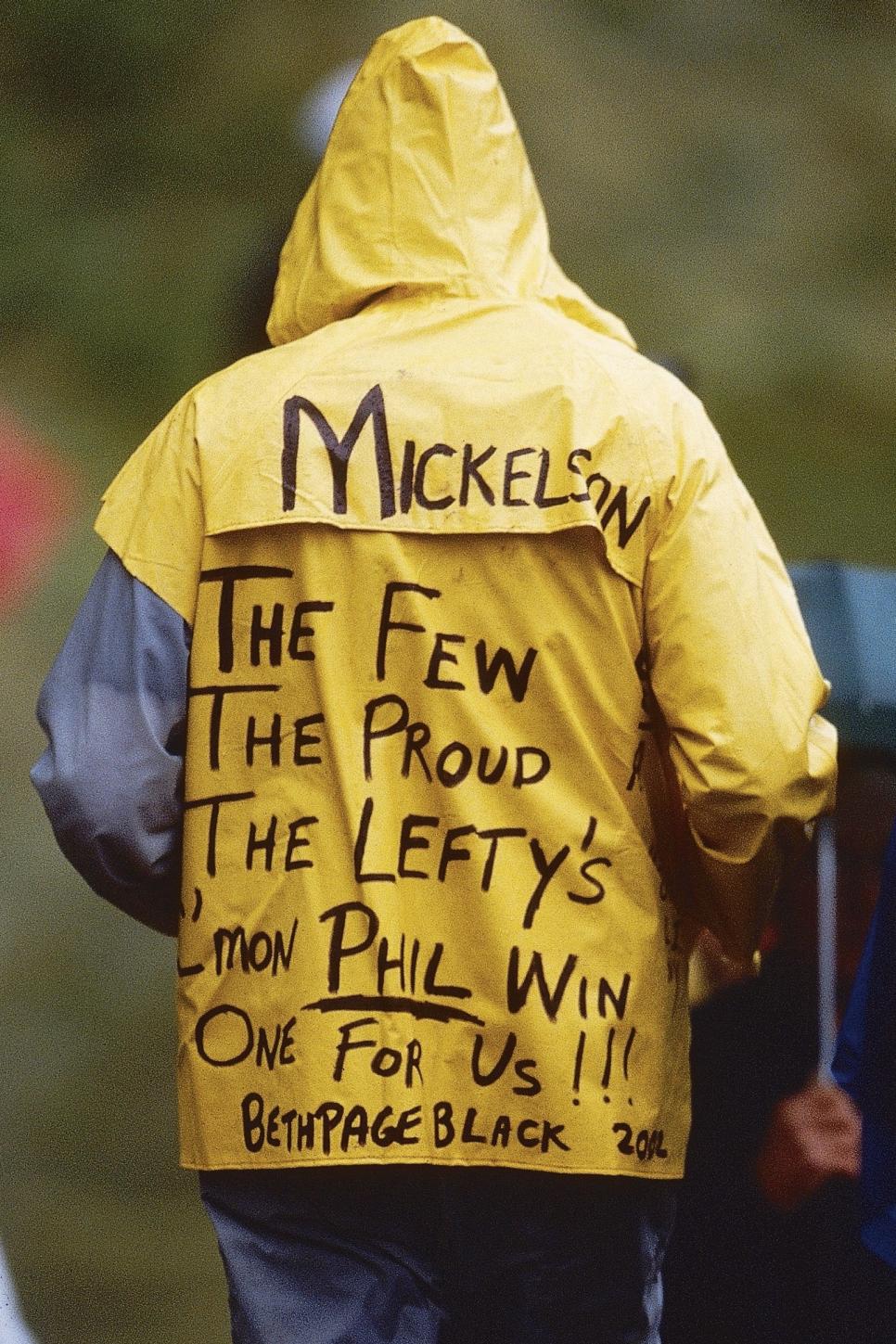

All along the way he signed every autograph and tipped big, leading cynics to wonder if it was all fake. Maybe, but in 2002 at the so-called People’s U.S. Open at Bethpage, the New York fans, with their acute radar for phony, adopted Mickelson as the “people’s champion.” Mickelson had come to be regarded as one of the players who, no matter how he played, was good for golf.

Al Tielemans

At that point in his career, the only thing about Mickelson that nettled the public was a propensity to fall short on the game’s biggest stages, which changed at the 2004 Masters, where when the Californian broke an 0-for-46 career tally in major championships with a dramatic victory. Twenty years later, however, that narrative has flipped. Mickelson has six major wins among his 45 victories and in the opinion of many is a top-10 all-time player. But fans have increasingly found him not only tougher to love, but to understand. And Mickelson is a pariah to much of the golf establishment that once embraced him.

It's been a gradual, circuitous and finally sudden journey, as big a reversal in public image as golf has ever seen.

It began after winless 2003 season so frustrating Mickelson took a break from tournaments to try pitching for the minor-league Toledo Mudhens. Clearly outgunned by Tiger Woods, he was at a crossroads, with even his most ardent fans fearing that their hero’s moment had passed. But resilience would prove to be Mickelson’s most underrated and enduring quality.

A hard look inward was overdue. Two years before, Mickelson, coming off loud criticism for trying a doomed shot over water on the 70th hole at Bay Hill, had doubled down on being Phil the Thrill. “I won’t ever change my style of play,” he told the press in what would be dubbed the Mickelson Manifesto. “I play my best when I play aggressive, when I attack, when I create shots … now, I may never win a major playing that way. But the fact is that if I change the way I play golf, one, I won’t enjoy it as much, and two, I won’t play to the level that I have been playing. So, I won’t ever change. Not tomorrow, Sunday, or at Augusta or the U.S. Open, or any tournament.”

Like more than a few of Mickelson’s pronouncements, the Manifesto was strident, assured but ultimately flawed. It took until on Jan. 1, 2004, for the son who drove his parents to read guides on “the strong-willed child” to relent. With instructor Rick Smith he worked on being less reliant on magic hands and timing, and more on a shortened backswing and shallower plane. He also began deferring to early data pioneer Dave Pelz, who got him out of some bad habits with his wedges. Finally, Mickelson submitted to an eating and exercise regimen, trimming 15 pounds, some of it presumably the subcutaneous fat Mickelson had claimed he was genetically stuck with. He then promptly won his first tournament of the season at the Bob Hope.

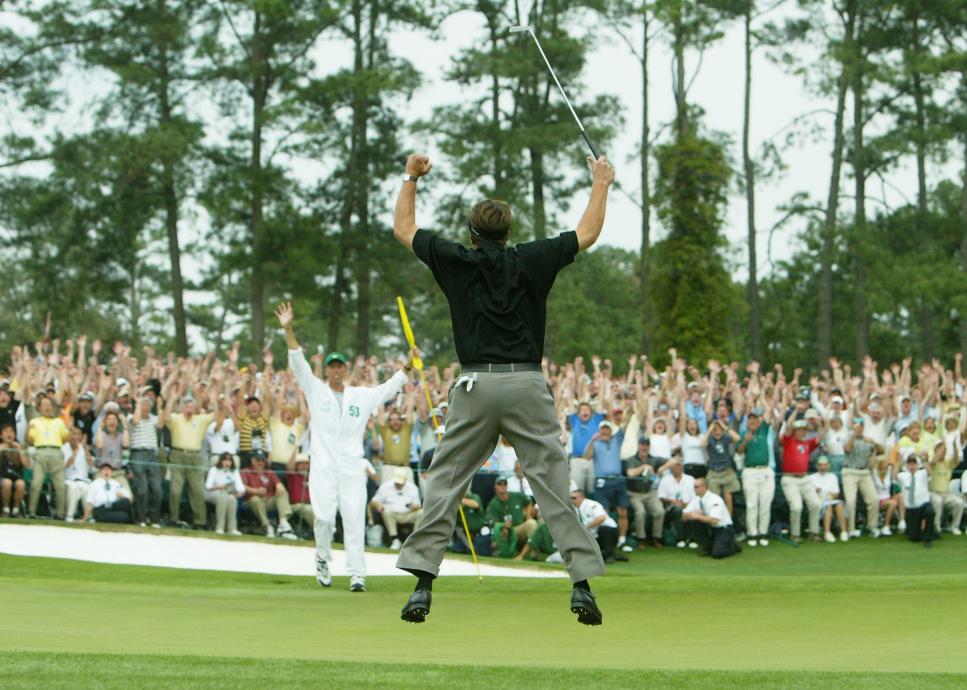

He came to the Masters better prepared than he’d ever been for a major. For three rounds, Mickelson was unusually steady, starting Sunday not having made a bogey for 32 holes and tied for the lead with Chris DiMarco. Three bogeys on the front nine, however, saw him trailing Ernie Els by three when he reached the par-3 12th. But when Mickelson sent a bold 8-iron directly at the flag and holed a 12-footer, it was the start of five birdies over the last seven.

As the 18th, an 18-foot downhiller with a right-to-left break, rolled toward the cup, Jim Nantz intoned, “Is it this time? Yes! At long last!” The image of a jubilant but barely airborne reaction became Mickelson’s logo, golf’s somewhat freighted version of Jordan’s Jumpman, although Phil deadpans that photographers caught him on the way up.

Phil Mickelson jumps in the air after making birdie on the 18th hole to win the 2004 Masters.

Andrew Redington

It was a major breakthrough. Mickelson won the PGA the next year hitting Smith-influenced fades—and in the next major, the 2006 Masters, he dominated with two drivers. Going for three in a row at Winged Foot, Mickelson put on the short-game demonstration of his or perhaps anyone’s life and got to the 72nd tee leading by one. But both his tee shot and recovery were horrible pushes that ended in a nightmarish double bogey and crushing loss.

Instead of finally passing Woods, who had run up nine major wins before Mickelson got his first one despite being five years younger, Mickelson’s close call at Winged Foot jolted Woods to go on an opportunistic tear that reestablished his dominance. Mickelson’s first great run was over, but the 2004 Masters remains the most important major of his career.

“A watershed event,” is how he described the tournament in the memoir of his victory, One Magical Sunday. “Essentially,” he wrote, “I took my new system of preparation and began applying it for every major.”

Fairly quickly, Mickelson’s public persona changed, and not for the better. Now a major winner with more influence, Mickelson began a pattern of taking on the golf establishment with his behavior and ideas, satisfying his self-appointed role as chief disrupter. Some of his ensuing conflicts meant spending public relations capital that temporarily affected his popularity. But as is the case in pro sports, winning takes care of everything. Mickelson found that three more major championship victories erased missteps and blowback nearly as well as his L-wedge could make up for missed greens.

The new power would test not just Mickelson’s growing entitlement, but his impulse control, always a work in progress. Sometimes it felt the motivation could be as simple as taking on a ‘fun challenge,” to use a favorite Mickelson phrase. At other times—as when he pettily used his 18th-green interview with NBC after winning the 2007 Deutsche Bank Championship to inform the audience that he was “torn” about showing up for the next FedEx Cup playoff event in Chicago (and he did not) because, "I've been asking the commissioner [Tim Finchem] to do a couple of things—and he has not done that. over disagreements with the tour, he did so because he could.

The pattern began at the 2004 Ryder Cup at Oakland Hills, where Mickelson, who had just switched equipment companies, decided to use his new ball and clubs for the first time in competition, which was criticized as a risky and selfish decision at a crucial event. Mickelson played badly, the U.S. got blown out at home, and Lefty took the most heat. But only until he won the 2005 PGA.

Phil Mickelson speaks in a press conference at the 2014 Ryder Cup.

Andrew Redington

A decade later, Mickelson was the central figure in the upheaval at the 2014 Ryder Cup. After the U.S. loss, he was coldly dismissive of captain Tom Watson’s leadership in a tense press conference. In a defense he would use again, Mickelson contended what he did as necessary to affect needed change, which became the Task Force. The validity of his actions would be judged by his performance and the outcome of the 2016 Ryder Cup at Hazeltine. Mickelson responded with a winning record and was widely vindicated as the U.S. routed the Europeans.

Mickelson’s petulance was on display in the third round of the 2018 U.S. Open at Shinnecock, when he struck a moving ball while it was speeding past the hole, incurring a two-stroke penalty. Was it a spontaneous act of frustration or meant as a shot at the USGA, whose past course setups had publicly riled Mickelson? Some saw it as consistent with Mickelson four years earlier having declined the Bob Jones Award, the USGA’s highest honor, becoming the first person ever to do so.

At about the same time, Mickelson became entangled in the Deans Foods insider-trading indictment of Billy Walters, a well-known gambler to whom Mickelson owned money. In 2012, Walters urged Mickelson to buy stock in Deans Foods. He used his earnings from the trade to pay Walters back, but after being questioned by the government, Mickelson consented to pay back “ill-gotten gains" of about $1 million. He was not prosecuted, but it was later revealed that if Walters’ case had been filed on either side of a two-year window rather than within that window, a different law would have been applied and could have led to Mickelson also being indicted.

The hits kept coming, but Mickelson did damage control. A 2018 ad for a shirt company he endorsed that featured Mickelson dancing and doing “the worm” was campy and well received. So were his increased social-media posts, including “Phireside with Phil” videos, along with tweets about calves, bombs, hellacious seeds, and life-changing coffee, in which Mickelson displayed a self-aware, Larry David-like touch in a pitch-perfect parody of himself.

Phil Mickelson poses with the Wanamaker Trophy after winning the 2021 PGA Championship.

Maddie Meyer/PGA of America

Then, in 2021 came Mickelson’s miracle PGA Championship at Kiawah Island, in which he became, at 50 years and 11 months, the oldest major winner ever. As he posed with the Wanamaker Trophy, the seemingly bulletproof Mickelson had a golf future that looked like a yellow brick road of Ryder Cup captaincies, the lead analyst chair on major network golf, handfuls of PGA Tour Champions victories, living legend reverence, along with the accompanying gold all of it entailed.

But it turned out, even as he was achieving such a crowning glory, Mickelson was breaking bad.

According to biographer Alan Shipnuck, in the weeks preceding Kiawah, Mickelson was exploring Saudi Arabia’s incursion into golf and was weighing a nine-figure offer to join a new rival tour. Though he didn’t sign at the time, Mickelson took a proactive role into hiring an attorney to write the operating agreement for the new league, as well as stirring up interest among fellow PGA Tour players.

Mickelson infamously gave his reasoning to Shipnuck for what most of golf saw as betrayal in comments he contended were off the record. Characterizing the Saudis as “scary motherfuckers” who were “sportwashing,” Mickelson asked rhetorically, “Knowing all this, why would I even consider it? Because this is a once in a lifetime opportunity to reshape how the PGA Tour operates.”

Mickelson would apologize for his remarks in a written statement, in which he unconvincingly presented himself as a martyr for a worthy cause. “Golf desperately needs change, and real change is always preceded by disruption,” he said. “I have always known that criticism would come with exploring anything new. I still chose to put myself at the forefront of this to inspire change, taking the hits publicly to do the work behind the scenes.”

Phil Mickelson and Yasir Al-Rumayyan talk during a pro-am at the 2022 LIV Golf event in London.

Charlie Crowhurst/LIV Golf

After being reviled when Shipnuck published the original quotes in February 2022, Mickelson was suspended that March by the PGA Tour for assisting LIV. The 32-year veteran voluntary exiled himself from tournament play, skipping the 2022 Masters and his defense of the PGA Championship. After coming back to play LIV’s debut event in London, Mickelson appeared the next week in the U.S. Open at Brookline, a hauntingly subdued figure in black clothing, dark shades and scruffy beard, and noticeably thinner. It was clear he had been through the mill, and his diminished figure brought to mind the most affecting words of his apology: “I have often failed myself and others, too. The past 10 years I have felt the pressure and stress slowly affecting me at a deeper level. I know I have not been my best …”

Mickelson’s gambling life provides a plausible motivation for his actions. According to Shipnuck’s sources, Mickelson claimed $40 million in gambling losses from 2010 to 2014. In Walter’s recent book, he asserts that over the last three decades, Mickelson bet $1 billion and lost $100 million. For all the money that would have come Mickelson’s way if he had never interacted with LIV, his losses are signals that he potentially needed even more, and more quickly.

Mickelson has admitted a gambling addiction, for which he has received professional help. He claimed the financial security of he and his family had not been threatened by his losses, but admitted the chaos gambling caused in their lives was “like a hurricane.”

Either way, as a bungling operator or a desperate gambling addict, Mickelson unwittingly gave LIV life at a crucial moment and hurt golf. The PGA Tour is central to the game as an aspirational model for all golfers, and with his actions, Mickelson damaged the sport more than any great player ever has, including LIV CEO Greg Norman, who couldn’t match Mickelson’s influence on today’s players.

While plenty of stars from the past have been self-destructive, the game, bigger than any individual, went on. But Mickelson recklessly took on too much risk when the stakes—the collective well-being of professional golf—were far larger than just his own fate. When he overplayed his hand in his rash disclosure to Shipnuck, Mickelson went down hard. But because adventurism entangled him with dangerous forces, the guy who had long been considered so good for the game pulled down professional golf with him.

Can Mickelson redeem himself? He seems to be trying, easing back into the mainstream golf world with instruction videos on the internet and a presence on X. But most of Mickelson’s missives have been LIV boosterism, leaving him far short of the elder statesman status that his previous station in the game would have conferred upon him in such an important moment.

Phil Mickelson and his caddie, brother Tim Mickelson, exchange fist bumps at the end of the 2023 Masters.

Patrick Smith

It can’t be forgotten that Mickelson finished second in last year’s Masters with a closing 65 punctuated with five birdies over the last seven holes—a run that mimicked his 2024 win. Considering that it was achieved in what must have been an awkward return to the tournament after staying away in 2022, and that he has yet to play a strong tournament in nearly three years with LIV, it was further testament to Mickelson’s resilience.

And, as he emphasized at Kiawah, Mickelson has a more intentional process for achieving focus. He has also added another mantra to his golf that he says the throes of gambling robbed him of with his family—“being present.” Even at 53, Mickelson’s established history of suddenly producing peak weeks still means he can’t be written off this week.

He will certainly be motivated to pull off something dramatic. He well knows what major victories have done for his public image in the past, and that image has never been in greater need of repair. But he is up against two huge obstacles. Resilience notwithstanding, there is diminishing evidence that he has enough ability to produce the kind of performance that might lead to forgiveness. And the sin he committed may be too great to be cleansed even by winning another major.

But it does bring up a fascinating thought experiment: How would Phil Mickelson winning the 2024 Masters affect golf?

It’s tempting to be romantic and see it as a unifying force. The probability would be closer to the opposite. For Mickelson personally, the impact would dwarf Kiawah’s, yet again and more than ever, using his talent as a life preserver.

If so, what would Phil do next? Well, if it was somehow something that could help pull golf out of the conflagration he helped create, Mickelson’s 2004 Masters would no longer be his most important major.

.png.rend.hgtvcom.406.203.suffix/1588791770594.png)