A forgotten Masters heartbreak

Masters 2024: This star amateur had to WD on the eve of the Masters. Why?

The 1973 Masters might not be one of the most famous editions, but like every Masters, it has its own identity—and remains notable for several reasons. Tommy Aaron, the man previously best known for incorrectly marking Roberto De Vicenzo’s scorecard at the 1968 Masters, won his lone major championship. Ironman Gary Player missed his lone Masters over a 53-year span from 1957-2009 while recovering from surgery (he returned a year later and won the second of three Masters titles). And Ben Crenshaw finished as low amateur for a second consecutive year, portending a hall-of-fame career that includes a pair of green jackets.

But you have to dig a bit deeper to discover another amateur’s result from that week that may be more intriguing than any of those indelible memories. Because it didn’t require a single swing. Those involved might even like to forget it ever happened.

At the time, Bruce Robertson was a standout sophomore on the Stanford golf team and one of the country’s best amateurs. Hailing from the San Francisco Bay Area, he has a résumé that included medalist honors at the 1971 Trans-Mississippi Amateur and 1972 Northern California Amateur, as well as a Northern Cal Junior title in 1970, and three consecutive Mid-Peninsula League victories in high school, the last of which he won by an incredible 28 shots.

In the summer after his freshman season, Robertson finished sixth at the U.S. Amateur behind winner Vinny Giles—during an eight-year period when the event was stroke play and the top eight got spots in the Masters—to earn an invite to Augusta National the following April. By many accounts, he was one of the sport’s rising stars.

“He had one of the nicest golf swings I've ever seen,” Tom Keelin, the Stanford golf team captain at the time, remembers. “Great rhythm and beautiful ball-striking.”

The week before the 1973 Masters, Robertson played for the victorious Cardinal at the Pacific Coast Invitational, where the lanky six-footer talked about how much he was looking forward to making his first of possibly many trips down Magnolia Lane. “It means a lot for me to play in the Masters,” Robertson said in an interview. “It should be a great experience.”

Only, it never happened.

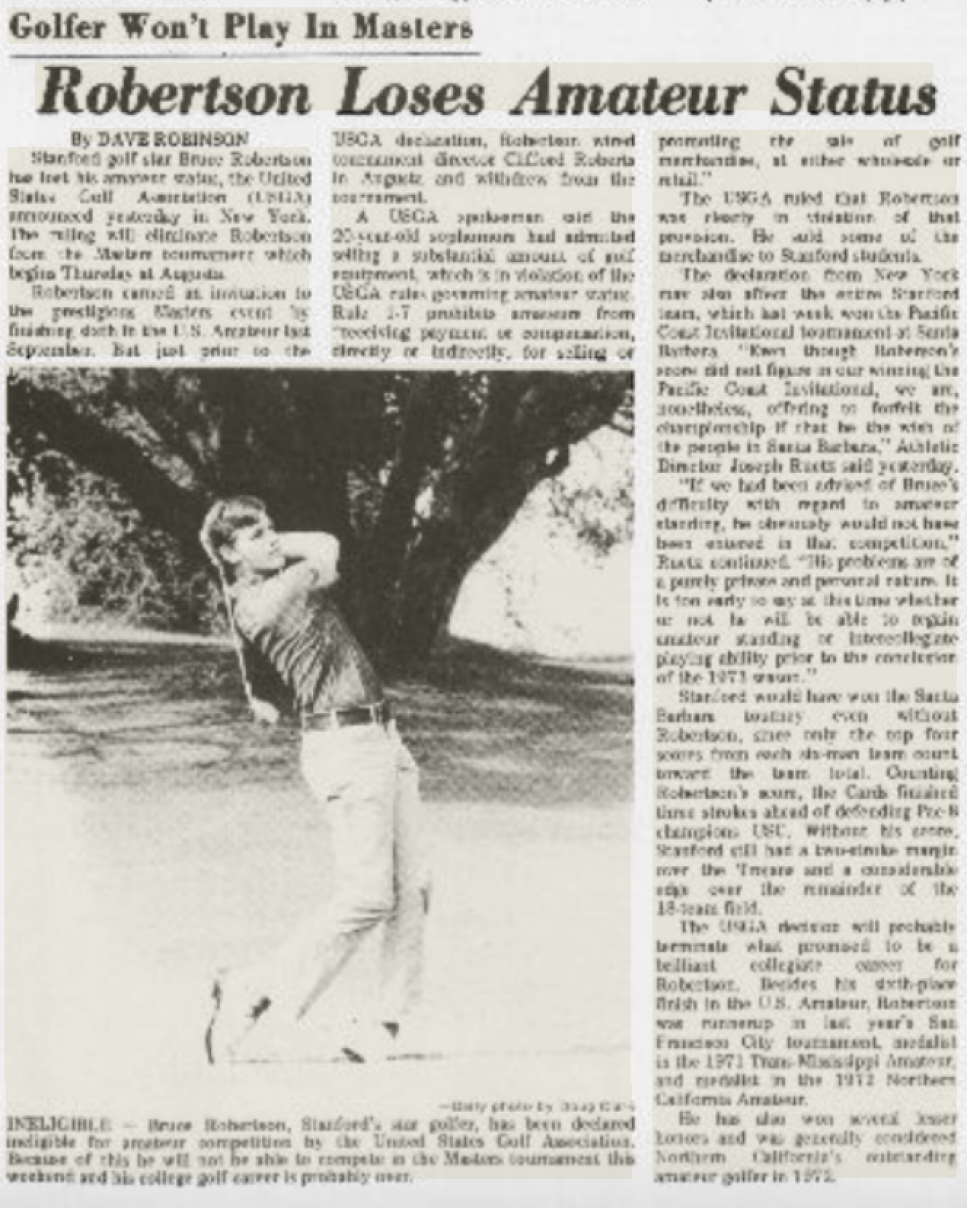

On April 2, 1973, the Monday of the Masters, the United States Golf Association announced through a press release that Bruce Robertson had forfeited his amateur status. The reason? Selling a “substantial amount” of golf equipment.

Robertson had violated Rule 1-7 of the Rules of Amateur Status, with the governing body concluding his status as a golfer on the Stanford team had played a role in the transactions. The 20-year-old Califonian had admitted to selling golf balls and clubs to other individuals, including teammates. Robertson had made money off the game, a clear violation of amateur golf regulations—remember, this was long before the days of NIL—and he didn’t fight the USGA’s decision.

The ruling meant Robertson would have to wait two years—a window from January of that year when it was determined his last sale occurred, to January 1975—to apply to be reinstated as an amateur. It was a standard punishment at the time, but one that rocked the golf world with versions of the Associated Press’ story circulating in newspapers around the country.

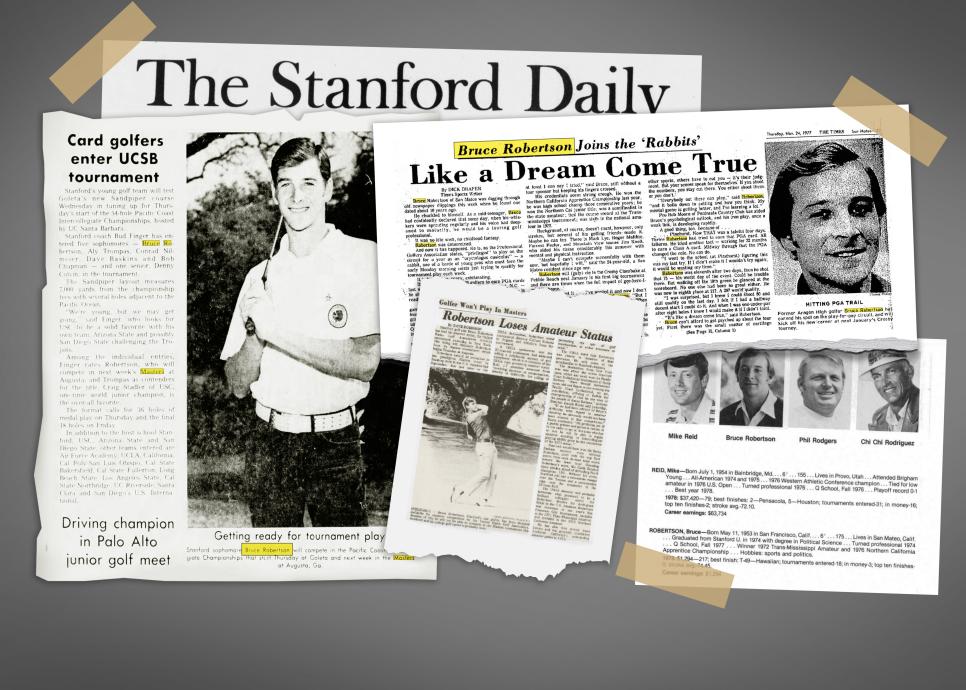

A story from the front page of the Stanford Daily on April 3, 1973.

The shocking announcement effectively ended Robertson’s promising collegiate golf career. Stanford’s athletic director, Joseph Ruetz, offered to forfeit the team’s win the following week and said this to the Stanford Daily in an article from April 3, 1973:

“If we had been advised of Bruce’s difficulty with regard to amateur standing, he obviously would not have been entered in that competition,” Ruetz added. “His problems are of a purely private and personal nature. It is too early to say at this time whether or not he will be able to regain amateur standing or intercollegiate playing ability prior to the conclusion of the 1973 season.”

Robertson never played for the Cardinal again, but more immediately, it meant the sophomore was barred from playing in the Masters tournament for which he had qualified. At some point over the weekend before that fateful Monday, Robertson wired Clifford Roberts to inform the Augusta National chairman that he was withdrawing from the tournament. Robertson’s telegram reached the club, but the player never made it to the property.

"He just got caught up in something he thought was OK and wasn't."Craig Winter, USGA senior director, rules of golf and amateur status

As crazy of a story as this seems, however, once the tournament began, it became somewhat of a forgotten matter. Oddly, there has been virtually nothing written about Robertson’s ordeal in the five decades since, although the great Michael Bamberger briefly mentioned it in his 2023 book, “The Ball In The Air.” That’s where this investigation began as I stumbled onto those two paragraphs this winter while catching up on some reading as I rehabbed from knee surgery. Bamberger concludes the short—and random—passage, “Bruce Robertson, as a national golf figure, was never heard from again.”

Defending champ Jack Nicklaus and winner Tommy Aaron with Augusta National chairman Clifford Roberts at the 1973 Masters.

Augusta National

It got me thinking. History shows that in 1973 Aaron slipped on the green jacket and Crenshaw collected the tournament’s silver cup before going on to bigger and better. But what happened to Bruce Robertson?

After some mostly fruitless research and newspaper searches, I hadn’t learned much more other than Robertson having a brief stint on the PGA Tour. And after unsuccessful attempts to contact him through the tour, Stanford, and Robertson’s former teammates, I finally found some answers thanks to the USGA’s Craig Winter. The senior director of rules of golf and amateur status dug through the organization’s archives, and while he wasn’t able to find much new information, he helped clarify what Robertson did wrong, how those rules have evolved since and the process of making such a ruling. Although there’s no indication of who reported Robertson or whether their goal was specifically to keep him from playing at Augusta National, someone clearly got the USGA’s attention in the months leading up to the 1973 Masters.

“We're not actively out policing the amateur space,” Winter said of the USGA’s general philosophy regarding these matters. “All of this stuff is reported to us. And we are compelled in many respects to look into things. And in his case … he just got caught up in something that he thought was OK and wasn't.”

Winter compared these reports to people calling in during golf broadcasts to report potential rules violations spotted on TV. But he confirmed this was a clear violation of Rule 1-7 and that just receiving equipment directly from a manufacturer at the time—which Robertson had, according to the file—was a violation of Rule 1-8 as well.

Ben Crenshaw during the 1973 Masters at which he earned low amateur honors for a second consecutive year.

Augusta National

“Amateur golf for most of the century and even into the early 2000s was still completely foreign to what we have today in the game where manufacturers are heavily involved with juniors and providing equipment,” Winter said. “And the amateur game has moved on quite a bit here in the last three years as well.”

The USGA’s rules regarding amateur status have loosened a lot since 1973. Although, technically, what Roberts did would only have been permitted after 2022, Winter acknowledged there have been other similar cases before then, though, that have avoided such a harsh penalty.

“This clearly had a pretty big impact in his life, and I'm not questioning it, because I just don't know all the specifics of what happened back then,” Winter said. “But we have over the years really tried with those situations that I've been involved in, what was the intent? How did it come about? Is there a way that we can make it right? Can we give the money to charity? And could we kind of unwind some of what had happened? And that may not be an answer that everybody in the public space likes to hear. … And so that type of a space that we inhabit on our committee is trying to provide answers that ultimately work in the best interest of the game of golf.”

There are plenty of great golfers who never make it to the Masters. There are plenty of tales of some coming close. But this is an extremely rare example of someone who did make it, and subsequently wasn’t allowed to play due to violating his amateur status. In fact, that’s pretty rare for tournament golf in general.

“I don't know of any in my time over the last 10, 15 years,” Winter said. “Even with the state golf association side of things, that would be pretty big news.”

It should be noted that in 1973, another amateur, Mark Hayes, forfeited his Masters exemption, but by his own decision to turn pro. Hayes, a future three-time PGA Tour winner and 1979 Ryder Cupper, would earn his way back to Augusta National in 1977 and play there five more times from 1980-1984, including a T-10 in 1982. Robertson never made it to the Masters, but he did wind up overlapping with Hayes on the PGA Tour.

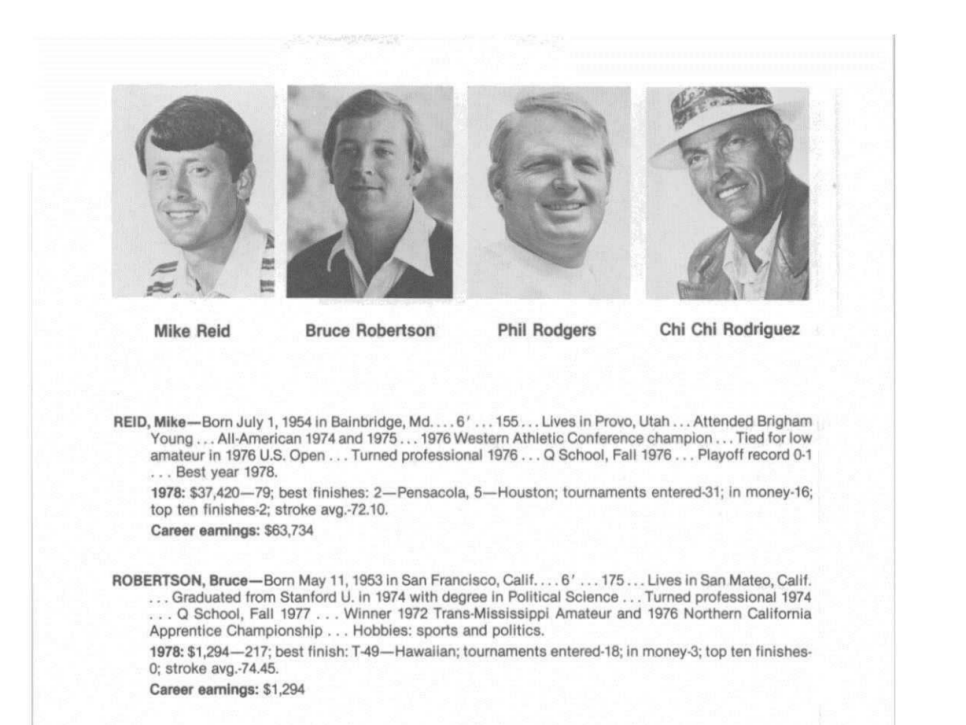

Bruce Robertson's bio from the 1979 PGA Tour media guide. He never played after 11 starts in 1978.

After losing his spot on the Stanford golf team, Robertson eventually turned pro, earned his PGA certification and became a club pro. He tried Q School several times before breaking through in the fall of 1977 with a T-6 at Pinehurst to earn PGA Tour status. The medalist of that event was Ed Fiori, who would win four times on the PGA Tour, including famously taking down a tour rookie named Tiger Woods at the 1996 Quad City Classic.

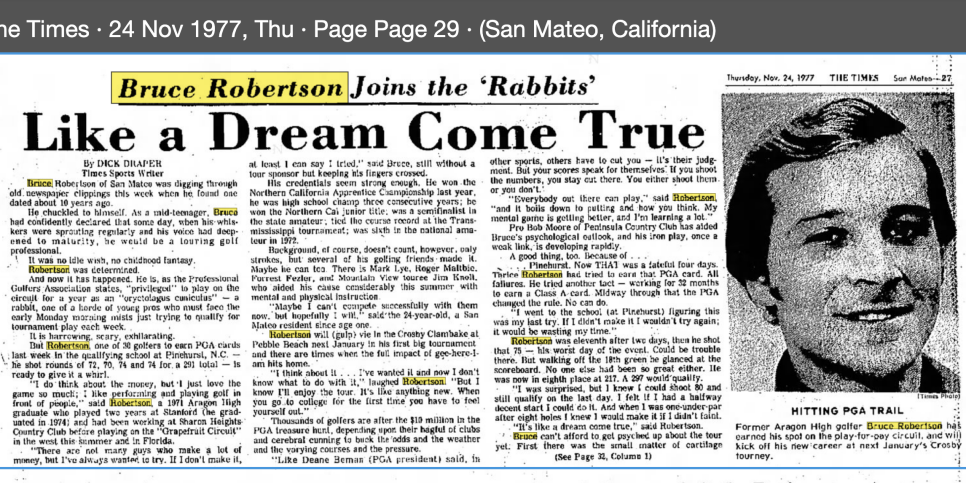

But earning your card back when Robertson did still meant having to Monday qualify most weeks with only the top 60 from the previous year’s money list and major champions being fully exempt. This tenuous status was something alluded to in a Nov. 24, 1977 article from Robertson’s hometown paper, The San Mateo Times, with the headline, “Bruce Robertson Joins the ‘Rabbits’” (a term for tour pros jumping from event to event chasing spots).

The story—the only one we could find focusing on Robertson after April 1973— notes Robertson’s stellar junior and amateur career, his two years as a player at Stanford, as well as him becoming an assistant pro at Sharon Heights Country Club in Menlo Park and winning the Northern California Apprentice Championship in 1976. But there is no mention of him losing his amateur status and having to withdraw from the 1973 Masters.

“If I don’t make it,” a 24-year-old Robertson told The Times ahead of the 1978 PGA Tour season, “at least I can say I tried.”

Robertson played in 11 events during the 1978 PGA Tour season, making six cuts and earning a total of $1,294. His best finish was a T-49 at the Hawaiian Open. His final event came in August at the American Optical Classic, where he withdrew after an opening 80. Robertson’s rookie season on tour turned out to be his last.

According to the USGA, Robertson filed to be reinstated as an amateur in 1979. He was told that because of his advanced professional status he would have to wait three years. The USGA has a record of him playing in the 1982 U.S. Amateur and the 1985 U.S. Mid-Amateur. After that, his career—both on and off the course—becomes a mystery.

"He had one of the nicest golf swings I've ever seen. Great rhythm and beautiful ball-striking."1973 Stanford golf captain Tom Keelin on former teammate Bruce Robertson

“I knew Bruce well and played with him a lot,” Keelin added. “But after the incident you mention, he just disappeared from the Stanford golf community. Most of us Stanford golf team alumni have kept in touch over the years. To this day, most of the best players, of which Bruce was one, can generally all find each other. Bruce is an exception.”

No one I could find at Stanford seemed to have contact info for him—although the school’s alumni association confirmed he graduated in 1975 with a degree in political science—and the PGA Tour’s last phone number for him was disconnected. A White Pages search turned up a few more disconnected numbers and messages to Stanford Facebook groups were a dead end. On the Friday afternoon before the 2024 Masters, I was feeling frustrated and disappointed as I put the finishing touches on what I knew was an incomplete story when an unexpected email showed up in my inbox.

It was from Bruce Robertson.

“Good afternoon, Alex. I understand you are trying to reach me. My contact information is below.”

Bruce and I set up a time to talk over the weekend, and when we finally spoke, the friendly voice on the other side of the phone said with a laugh, “I’m pretty much a hermit as you can see.” That had been my conclusion after struggling to track him down, but, of course, that’s not the entire story.

Robertson isn’t on social media of any kind, he hasn’t spoken to his former teammates in more than four decades and he hasn’t done a formal media interview in even longer, but he’s a happily married man with three grown stepchildren and four grandkids. And he has a regular group of golf buddies at Pinewild Country Club in Pinehurst, where he lives off two holes of the 48-hole facility—although this spring he is moving to Columbus, where his second wife, Sue, is from. Life is good for the soon-to-be 71-year-old, who retired in 2019 after putting that Stanford degree to good use with 40 years in the mortgage business. A back issue has limited him to playing two-to-three rounds per week, but he still plays to about a 5 handicap.

We talked about golf and Pinehurst and swap knee surgery stories for a good 10 minutes before I got to the real reason why I’ve been so interested in talking to him. Of course, Robertson knows why.

“I'm still a little ashamed of what happened, you know, and I’m not looking forward to seeing anything in print,” says Robertson, who left Stanford in December 1974 after graduating a semester early to pursue pro golf. “But I understand you’ve got a job to do.”

Throughout our 30-minute conversation, Robertson clearly enjoyed talking about other topics more—including the expansive amount of children’s TV programming available now when my 3-year-old interrupted us to get me to switch from “Gabby’s Dollhouse” to “Mickey Mouse’s Clubhouse”—but I appreciated his honesty regarding the USGA’s ruling in 1973. Heck, I appreciated him talking about such a painful memory at all.

"I made a mistake and I paid for it. I wish I could have played the Masters, but the USGA did the right thing."Bruce Robertson

Robertson was unaware he had been mentioned in Bamberger’s book and he confirmed he hasn’t spoken publicly about being stripped of his amateur status. ”I’m kind of surprised I’m talking to you about it,” he blurted out at one point. But in addition to still feeling bad about what happened more than 50 years ago, he said the other reason for that is even simpler: “Nobody’s asked.”

Well, here I was asking. Was it wrong to open up old wounds? Was I being selfish to solve some old mystery that really didn’t need any solving? Sure, I have a job to do, but no one asked me to work on this story and none of my bosses even knew I had been working on it. I’m not sure why I was so fascinated by Bruce’s story. Why for weeks I kept old Stanford media guides and the 1973 Masters Wikipedia page open as tabs in my browser, and kept screenshots of old newspaper clippings on my desktop. I guess, mostly, I thought that at the very least Robertson deserved to have his side of the story told—even after all this time.

“I made a mistake and I paid for it,” Robertson said when I finally brought up the elephant in the room. “I wish that I could have played the Masters, but you know, the USGA did the right thing.”

So the questions continued. What about the USGA’s report that it was a “Substantial amount?”

“That’s exactly correct.”

OK then. Robertson also confirmed he didn’t know he was breaking a rule. And that had he known, he “absolutely” wouldn’t have done it, which makes the entire saga even more tragic.

So why did you do it?

“Make money, buy some tires for my car,” Robertson says. “I don't know.”

Who do you think turned you in?

“No idea and I’ve never tried to find out. It doesn’t matter.”

How did you find out that the USGA was looking into you?

“Sandy Tatum called me and said, ‘I'd like you to meet me in my office in San Francisco,’” Robertson says of the legendary amateur golfer, fellow Cardinal, and then USGA Executive Committee member. “I met him and he told me, and I guess the best way I could put it is I was just numb.”

When did you find out about the actual decision?

“Saturday.”

The Saturday before the Masters?

“Yes.”

Wait, WHAT?!

“My understanding is there was a lot of talk that we do it before the Masters or after the Masters,” Robertson says, “I don't know what went on behind the scenes. I understand the USGA’s point and I think they did it the right way … in retrospect.”

I couldn’t have been more impressed with how Robertson seems to have handled it all—I just wish he didn’t have to feel the shame that has followed him for more than five decades. Here had been a 20-year-old college kid just looking to put a little money in his pocket, who had lost what turned out to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity at virtually the last minute. But yet he seems to harbor no ill will toward anyone over it and continues to take full responsibility for his actions.

“You can look back and say, I wish I'd done things differently,” Robertson reasons. “But you know, it is what it is.”

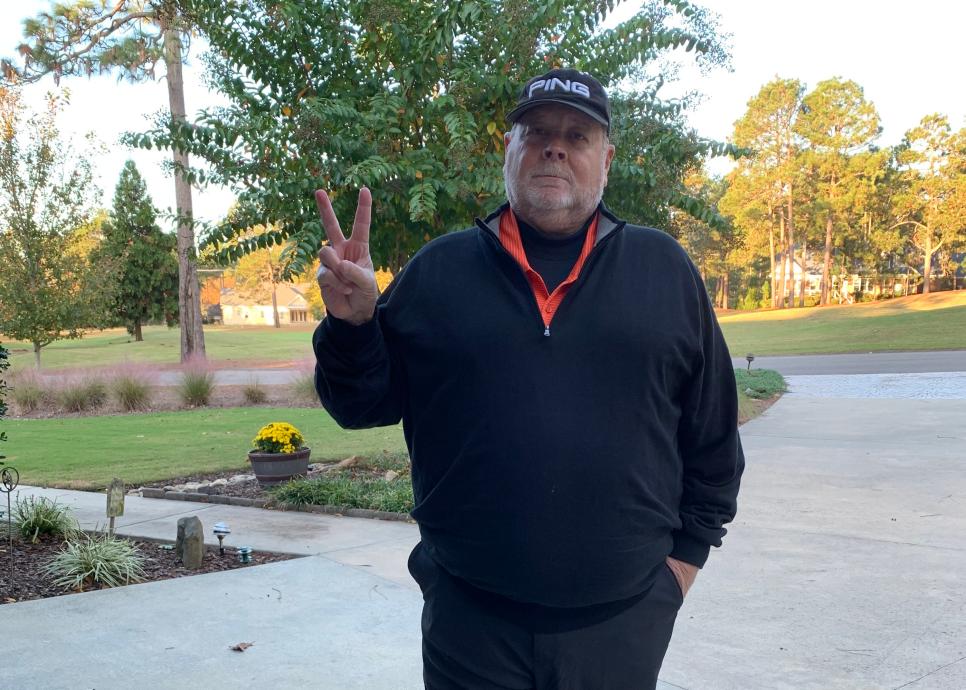

A retired Bruce Robertson at his home in Pinehurst.

A few years ago, Dave Shedloski wrote about the golfers who only played in one Masters. And Joel Beall recently wrote about the agony of some near Masters champions, a title that earns you a lifetime pass down Magnolia Lane. But all those guys all had the opportunity to make that drive at least once to tee it up at Augusta National. Depending on how you look at this unfortunate situation, Robertson squandered—or, was robbed of—his only chance.

Aside from the heartbreak, part of what makes this story so interesting is how different the landscape is for current amateur golfers and college athletes in general. The USGA and NCAA have greatly loosened the rules surrounding amateurism and current student-athletes like Caitlin Clark and Arch Manning make millions of dollars through NIL deals.

That’s why you see amateur golfers at both the Masters and the Augusta National Women’s Amateur adorned in logos and looking like tour pros. And at the 2023 Masters, Texas A&M’s Sam Bennett cashed in even more after contending for much of the week and winding up in Butler Cabin as the low amateur with green jacket winner Jon Rahm. But none of that bothers Robertson.

“You look at Reggie Bush and what happened to him in football, those were the rules,” Robertson says of the former USC star who was stripped of the 2005 Heisman Trophy for receiving improper benefits while in school. “Rules change. You know, it's like they had a top 60 when I played on tour. Now they've got an unlimited tour. Things change. So you can't look back. It's different.”

It’s hard for Robertson to know how differently things would have turned out had he been able to play in the Masters that week. The week after earning his PGA Tour card, he had surgery to remove the meniscus in his right knee. And after qualifying for three consecutive early-season events in 1978, more swelling caused him to take a three-month break that included six weeks in a full-leg cast. Not ideal for someone trying to earn a living against the best golfers in the world. And then there was something else that Robertson says he’s only told a few people about.

After a fantastic fall his freshman year at Stanford, Robertson had his first epileptic seizure that winter. They began happening more frequently and always at night other than one time when he was hitting balls at Olympic Club. Robertson says his condition affected him for years and made him more inconsistent on the course as it took a while to be properly medicated. And the seizures only stopped completely 15 years ago when he was diagnosed with sleep apnea and given a CPAP machine to sleep with. Still, despite all the setbacks that kept him from possibly reaching his full potential, Robertson is proud of what he accomplished in the sport.

“You know, if I hadn't made the tour, it would have been a lot more difficult,” Robertson says of transitioning away from being a full-time golfer and into a regular desk job. “I made it. I didn't do nearly as well as I wanted, but I made it.”

After the 1985 U.S. Mid-Am, Robertson never played serious golf again. Between being busy with work, and eventually meeting Sue and being involved with her three kids’ own athletic pursuits, Bruce says he barely played during the 1990s. It was also during this period when the self-described hermit says he lost touch with most of his contacts from the game, although he still counts fellow former PGA Tour pros Pat McGowan and Mark Lye as close friends. At some point, he also lost touch with a certain bittersweet memento.

“I don’t even know where it is,” Robertson says of the 1973 Masters invite he received from Augusta National, “but I know I’ve got it someplace.”

While 1973 is a distant memory, Robertson fondly recalls playing with Crenshaw in the final round of the U.S. Amateur the previous year. And, of course, he’s thought about what that week at Augusta National would have been like. How could you not let your mind wander down Magnolia Lane when you once held the keys to the front gate?

“Well, I think staying in the Crow's Nest was the first thing, obviously,” Robertson says of the famed clubhouse accommodations for amateurs in the tournament. “And then, just being able to see the golf course and play the golf course.”

But what happened a half century ago hasn’t kept Robertson from watching the Masters, even if he’s never been lucky enough to win a ticket to the tournament. Maybe Augusta National's powers that be can rig the lottery in his favor next year, because, after hearing Bruce’s story, he seems owed at least that much. In the meantime, Robertson will once again be camped out on his couch this week witnessing the latest cast of golfers trying to win a green jacket or a silver cup—and vying to become one of those lasting memories for golf fans everywhere.

“How do you miss the Masters?” he asks.