News

The Massacre at Winged Foot: An oral history of the 1974 U.S. Open

Leonard Kamsler/Popperfoto

Editor’s note: In celebration of Golf Digest's 70th anniversary, we’re revisiting the best literature and journalism we’ve ever published. Catch up on earlier installments.

Dick Schaap, the late sports journalist, wrote two diary-like books that changed the genre of golf writing. In 1970, he published PRO: Frank Beard on the Golf Tour, a candid chronicle of the previous year’s leading money-winner week by week. Then in 1974, Schaap enlisted a dozen reporters, including Dave Anderson, who later won the Pulitzer Prize, to help record a minute-by-minute account of the pivotal U.S. Open called Massacre at Winged Foot, which led USGA championship chairman Sandy Tatum to say for the first time: “We’re not trying to embarrass the best players in the world; we’re trying to identify them.”

It was Schaap’s technique that led to another ground-breaking format for Golf Digest in which the magazine previews major championships by interviewing as many as 50 or 60 journalists, fans, officials, members, caddies and players who recall intimate and iconic moments from past events at the venue. In June 2006, one of the most memorable of these anniversary pieces was drawn again from the 1974 U.S. Open, but this time retold by veteran reporter Peter McCleery through the words of the observers.

I happened to be in the gallery in 1974 watching my first U.S. Open, having driven from Philadelphia after high school graduation and staying overnight in an orange VW pop-up camper somewhere in Westchester County in New York. A muny player who had never seen a country club course up until that time, I was astounded by the length and depth of the rough. I knelt down and touched the putting surface before a marshal chased me away; I’d not imagined such perfection was possible in grass. On Sunday in the final round, I positioned myself in the last row of the grandstand beside the 18th green, where I could stand up and look back at the classic par-3 10th hole to see Arnold Palmer, then 44 and still in the hunt, hole a bunker shot for a 2 and shake the poles beneath the stands with an eruption of cheers. A couple of hours later, I witnessed Hale Irwin come through 18 and strike his historic 2-iron onto the final green to finish seven over par and win the championship. That Open was full of memories for everyone who attended, as McCleery’s story demonstrates almost a half century later. —Jerry Tarde

* * *

The searing images remain decades later: Jack Nicklaus putting off the slick, sloping first green the first day; a car driving over the same green before the second round and doing no discernible damage; a fan losing teeth by taking a tee ball directly to the face. In one way or another, all of those events left a mark.

It was a different era in golf, with persimmon and balata for equipment and local youngsters as caddies. Corporate tents and automatic sellouts were not yet part of the landscape for the Open, though IBM provided a new level of statistical analysis. Arnold Palmer led by two strokes on Saturday and remained the fan favorite at age 44 as he attempted to win his first major title in a decade. Gary Player, 38, had Grand Slam aspirations after winning the Masters and taking the first-round lead at Winged Foot; later that year he would win the British Open and finish seventh in the PGA. Tom Watson, 24, seeking his first victory of any kind on tour, led entering the final round. And Hale Irwin, 29, was about to win the first of his three Opens.

As the championship returns to Winged Foot's West Course, we revisited that memorable week with the key participants and those with unique insight from the periphery. Many players had blocked out the damage, but others were willing to revisit painful memories. Far more than any other modern Open, Winged Foot was remembered not for shotmaking but for how damn hard it played.

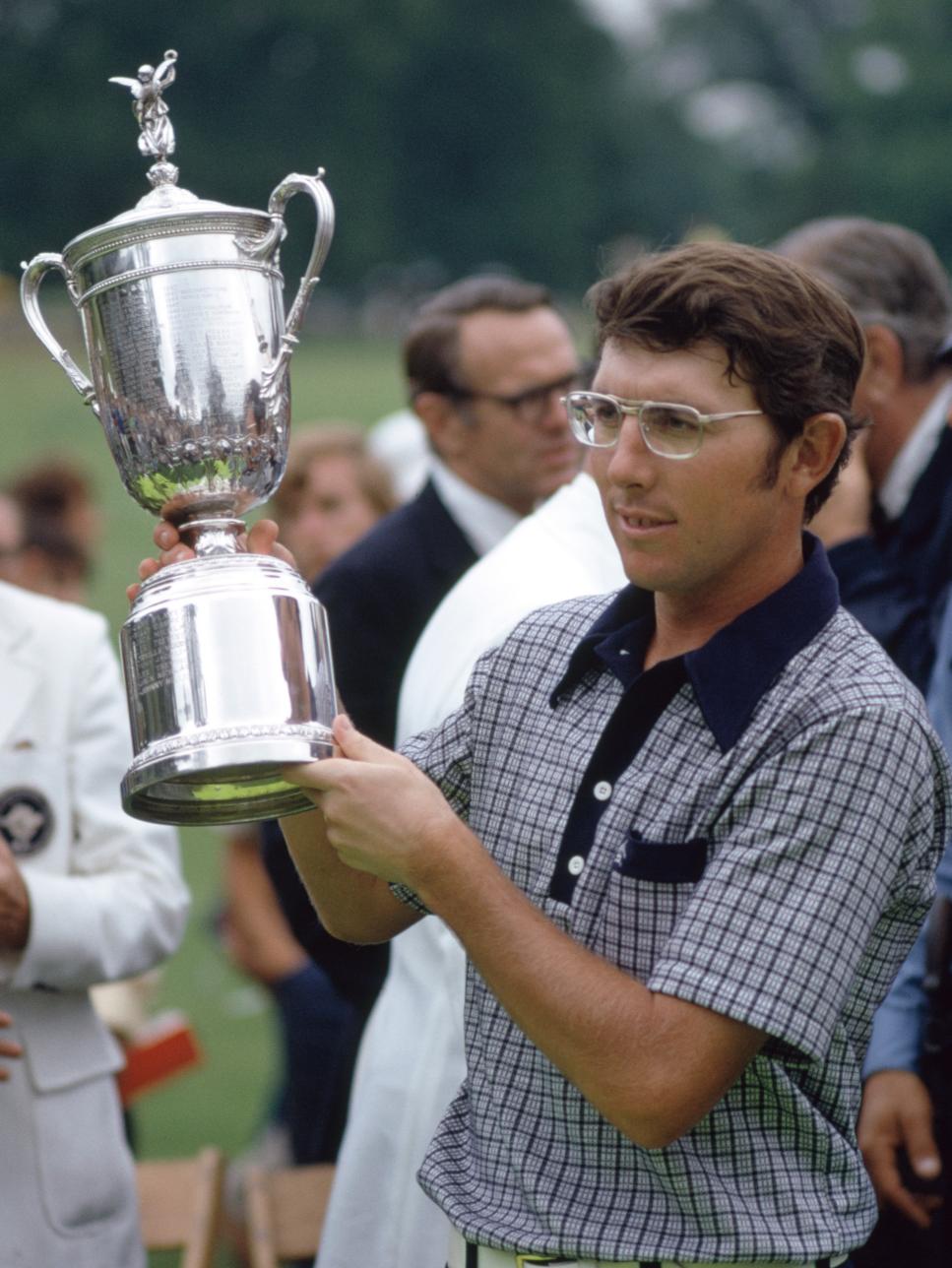

Johnny Miller insisted that Winged Foot's rough was 10 inches in some areas.

John D. Hanlon

PREMONITIONS

Sally Irwin (Hale Irwin's wife): I was taking Hale to the airport to go back on tour three weeks before Winged Foot. I was having a difficult pregnancy and staying home in St. Louis. He told me, "I dreamt I won the Open." Hale dreams a lot, and they're very vivid. I said, "Good, honey."

Hale Irwin: I know I've had that feeling several times in my career. It must've been one of them.

Leonard Thompson: Hale rode from Philadelphia [the previous tour stop] with me. I had a car, he didn't. We played a practice round at Winged Foot, and I remember hitting it like 15 feet, 10 feet or 12 feet from the hole and putting it 10 or 12 feet past every time. They started calling me Anvil Hands. To this day, Hale calls me that.

Hale Irwin: It wasn't just Leonard; we were all dumbfounded by how difficult it was. It was easily the most difficult golf course I had ever seen.

Jim Colbert: Probably the hardest course of all time. No matter how hard the USGA sets up Winged Foot this year, there is no way it'll be as tough as it was in 1974.

Gary Koch: I got there Monday and played a practice round with Andy. Bean, my teammate at Florida who also qualified as an amateur. We got to the first tee, and Bert Yancey walked up and said, "Mind if I join you?" We said, "Sure." We both knew Bert, and he was kind of different. He hits it down the middle of the fairway and has a 6-iron to the green. The pin was front-center, and he hit it about 30 feet behind the hole and putted it right off the green. He turned around and walked right back down the fairway saying, "Where in the hell can I find a USGA official?" That's how the week started.

Steve Melnyk: I remember starting a practice round on the 10th hole with six balls in my bag. I hit two tee shots on 17 into the right rough and couldn't find either one of them, and I was out of balls. I hadn't hit one out of play, but I was done after 7½ holes.

Ted Horton (Winged Foot course superintendent in 1974): It was the most consistent, deepest rough in an Open up until then. We were very proud of the fact that that was the first Open that had uniform six-inch rough.

Johnny Miller: Forget the six—I know six-inch rough. It varied from six to a legitimate 10 inches.

Hale Irwin: I remember in one practice round hitting it over the second green on the other side of the bunkers and picking up the grass with my hands. It was well over a foot long; just a tangled mess. That's just a hosel-wrapper.

Ted Horton: They had trouble finding their ankles, much less the golf ball. It kind of shocked the world.

Johnny Miller: I like to measure U.S. Open rough by how far you'd be able to advance 100 balls if you hit into 100 different lies. At Oakmont in '73 you'd average about 140 yards. Some recent courses haven't had any rough to speak of; at Olympia Fields and Shinnecock they probably averaged about 190 yards from the rough. At Winged Foot in '74 the average was 80 yards; all you did was hit wedge or sand wedge out. It was just unheard-of rough. It's never been seen before or since.

Frank Beard: In a practice round I played with Jerry McGee, he hit his tee shot in the right rough on 18 and took a full swing, but the ball didn't go three feet. Some of the fans were razzing him. I thought Jerry was going to go after one of them.

Jay FitzGerald (Winged Foot member and former Golf Digest president and CEO): I was sitting in the grandstands when McGee's group came through. Some fans had had a few beers and gave it a few tee-hees: "These are supposed to be professional golfers?" one of them said. McGee's ball was 25 yards from the green, and he told the guy, "I'll give you three swings, give you $100 if you can hit one of them on." The guy could barely advance it.

Tom Kite: Around the same time, a bunch of newspapers were doing surveys asking the fans, "What would you rather see, people struggle and shoot high scores, or a birdie-fest?" And the majority said they'd rather see players struggle, because they could relate to it.

Hubert Green: It was like going against Ali in his prime; you keep getting knocked down, and you get back up. But it's the U.S. Open; it's not Hartford. How many times do you hear that the U.S. Open is too easy?

Gary Player: I'd love to see an Open like that again. That's what a major championship is supposed to find out: Who is the best striker? Everybody I meet these days says the same thing: "Why don't they have a requirement for straight hitting?" Isn't that what we're all striving for?

Tom Weiskopf: It was pretty obvious after '73 [Miller's final-round 63 the year before at Oakmont to rally from a six-stroke deficit] that we were going to have the conditions that we played under. It was a typical knee-jerk reaction by the USGA.

Johnny Miller: Everybody was telling me it was my fault. It was like a backhanded compliment. The USGA denied it, but years later it started leaking out that it was in response to what I did at Oakmont. Oakmont was supposed to be the hardest course in America.

Hubert Green: The members at Winged Foot said, "This [63] isn't going to happen to our golf course." That gave the USGA carte blanche to do what they wanted with the course.

Frank (Sandy) Tatum (then chairman of the USGA's championship committee): It has come up fairly frequently, but what happened the year before had nothing whatsoever to do with the setup of Winged Foot. I can testify absolutely to that, because it was my setup.

It's important to recognize what happened at Oakmont. I want to be careful not to detract one iota from Johnny Miller's performance, because what a performance it was. Before the final round at Oakmont, the irrigation system did not malfunction, but the water had been left on by error. And the golf course never recovered.

The responsibility for the setup at Winged Foot was thoroughly mine, and I was never uncomfortable with it. I'm not defending myself; if I'd done something I regretted, I'd be telling you. In my mind and heart I was convinced it would be the ultimate test of what the elite players could do. If they played a hole at an extraordinarily effective level, a birdie was available. And if they didn't play it effectively, they were going to pay a penalty.

Sandy Tatum contended that Winged Foot was not made to be more brutal because of the results the year before at Oakmont, where Johnny Miller shot 63.

Leonard Kamsler/Popperfoto

Hale Irwin: What's fair? Hearing all the complaints—I shouldn't say complaints, but observing the behavior and most of the comments—it was going to be extremely taxing on patience, and over par was going to win. There was no way you could find more birdies than bogeys on that golf course.

Tom Weiskopf: There was a lot of betting going on about what the winning score might be. It was almost like being in Las Vegas: Pick a player. I think 290 [10 over par] was the basic bet.

Butch Harmon (son of Claude Harmon, Winged Foot's head professional at the time): Dad was convinced nobody would break par. Dad was in the men's grill one day and said, "I'm taking all bets, all comers."

Tom Callahan (Cincinnati Enquirer columnist, now at Golf Digest): I remember how happy the members were at the devastation. They were thrilled that seven over ended up winning.

As a caddie at Winged Foot, current New York Giants Vice President Chris Mara was dubbed as a Johnny Miller lookalike by the club's caddiemaster.

Cindy Ord

KIDS AS CADDIES

It was a different era for caddies in 1974. Back then the USGA didn't allow pros to use their tour caddies at the Open; players were required to use club caddies (a practice that ended after the next year's Open at Medinah). Players and caddies at Winged Foot were picked by lottery.

Chris Mara, then age 17, now a member of the New York Giants front office: My family were members, and I caddied in that tournament. The caddiemaster was a cranky Irishman named Gene Hayden, and he thought I looked like Johnny Miller, used to call me Johnny Miller. Everybody thought the fix was going to be in, and I was going to be the one who got Johnny Miller. The players started arriving Saturday and Sunday, but Miller wasn't there yet. On Monday I drew a club pro from Iowa, Brad Schuchat, who missed the cut [80-77]. He was a great guy, but I don't think he'd seen rough like that in Des Moines.

Peter McGarey (Hale Irwin's caddie, then age 16, and later a real estate developer in Cincinnati): I had been caddieing at Winged Foot since I was 9 years old growing up in Larchmont. Back then, including tip, you'd get about eight bucks when you caddied for a member. When I caddied in the 1972 Women's Open at Winged Foot, my lady [Jane Booth] came in sixth, and I think I got 65 bucks for the week.

Our family moved to Scottsdale after that, but I wrote the club and said I wanted to come back and caddie in the Open. My family went to Mexico for vacation that week; I went to Winged Foot and drew Hale Irwin in the pool. Being from Arizona, I started out wearing hiking boots on the course, but they were leaving some impressions. Hale suggested I'd better get some tennis shoes.

Hale Irwin: At that point I didn't have a regular caddie on tour. I didn't mind some of the young kids, because I got my own yardages; I did everything on my own. He was late one day and got chastised for that and kind of learned a lesson, but it was fine.

Peter McGarey: He must be talking about the day I was trying to sneak a peek at Arnold Palmer coming up the ninth hole. I mean, hey, it was Arnold Palmer. I can't remember if it was a practice round or the actual tournament, but Hale came and grabbed me. The only reason he knew it was me was because my jumpsuit had his name on the back.

Steve Garagiola (son of former baseball player and broadcaster Joe Garagiola, caddie for Jim Colbert, and a newscaster): I was 19 years old and either playing golf or caddieing every day. I'd paced off the course: every tree, bench, ball washer–everything. Colbert was pretty intense; he kind of scared me at first. He told me, "Don't ever tell me what club to hit, because I hit every one of them 10 different ways. All I want is the yardage to the middle of each green and a clean club on every shot.'' I gave him a club in a practice round that still had a clump of mud from his last shot, and he said, "Son, the only thing I told you was to always give me a clean club.''

He could see that I knew the course, so we started reading greens together. The [New York] Daily News ran a picture of us one day on the back page, reading a putt. I got Jim to autograph it years later. He wrote, "Steve, you did a great job. I just came up a little short.''

I made $500 for the week. I've still got a photocopy of that check. I would have paid to be around guys like that.

Peter McGarey: I'd rather not say how much I got paid. If Hale doesn't want to tell you, I'll keep it between us. Believe me, I was very satisfied with what I got. Hale got $35,000 for winning, and I didn't get 10 percent, but I definitely got more than 2 percent [the normal fee for many at the time, which would have been $700]. I came back to Arizona, and one of the things I did with the money was buy my mom new tires for her car. Let's put it this way: It was plenty of money for a 16-year-old to enjoy for the entire summer.

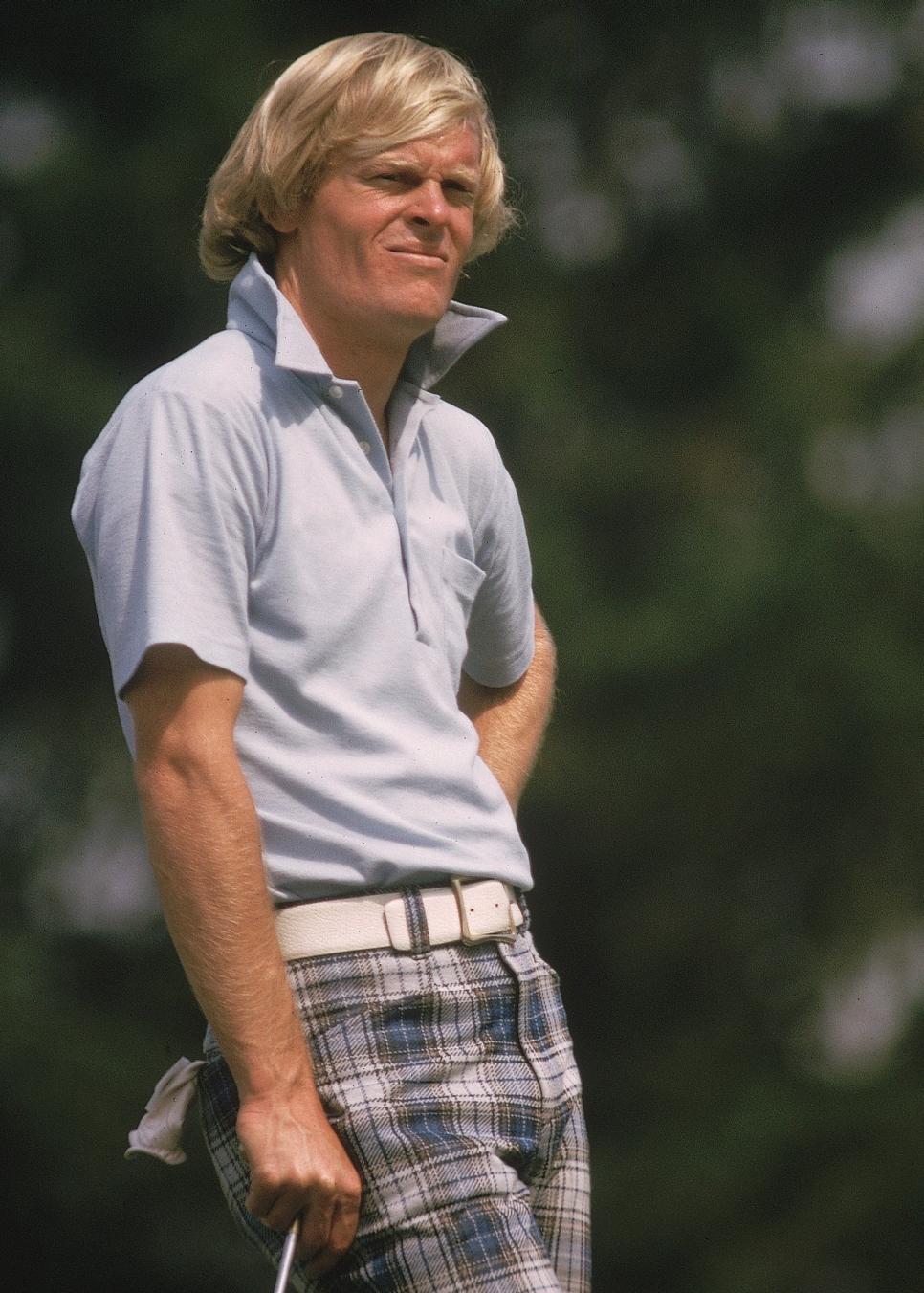

Jack Nicklaus couldn't believe it when he putted off the green on the first hole of the 1974 U.S. Open at Winged Foot.

John D. Hanlon

THE PUTT THAT SHOOK THE FIELD

The first-round carnage produced a scoring average of nearly eight shots over par; 44 players shot 80 or worse. Gary Player led at even-par 70, but what most everyone at Winged Foot was talking about that day was Jack Nicklaus putting a ball off the front of the first green.

Bill Erfurth (club pro from Glencoe, Ill.): I was 30 to 40 feet above that hole and rolled it right off the green and four-putted. Nicklaus was in the group behind me, and as we went to the next hole I noticed a ball behind me go up on the same level. I said, "He's probably going to do the same thing." And he did.

Jim Colbert (paired with Nicklaus and Hubert Green): I remember getting on the green and having a 30-footer for par. Jack was pin-high to the left, above the hole, just outside me.

Hubert Green: Jim and I were trying to decide who'd putt next after Jack. When Jack hit his putt, at impact we both said, "Jack is."

Jim Colbert: He putted across the green, toward the hole, and as it started going down the hill it rolled right over my coin. He lost ground. . . . He was still away, maybe 35 feet. Now this is the greatest Open player of all time, right? When that thing quit rolling, he was stark white, the color of my shirt. I’ll never forget that. “Never seen a green that fast,” he says.

Steve Garagiola: Nicklaus got this look, a twinkle in his eyes. It wasn't like he was mad, but puzzled, amused, frustrated.

Jack Nicklaus: "It was a downhill putt, behind the hole, and the pin was on a crest. It was quicker than I thought, and all of a sudden the ball got away from me. Next thing I knew, the ball kept rolling and rolling and rolled right off the green. I imagine I wasn't the only one who putted off that green that day. In fact, my guess is quite a few did.

Steve Melnyk: I played behind Nicklaus and saw what happened to him and thought, Well, I think we're in for a long day . . . a long week.

Hubert Green: When Jack putts the ball off the green, you say, "My God, what are we mere mortals going to do out here?"

Tom Jenkins: I almost turned around and went back in the clubhouse and didn't even start the U.S. Open.

Ted Horton: I was out there watching Jack. That's when I kind of knew we had done something right, from my perspective. You probably wouldn't want to get Winged Foot's greens any faster than we did that week.

Mark Mulvoy (then a writer at Sports Illustrated, and later the managing editor): I had been Jack's ghostwriter for five or six years on some instruction articles and was following him the first day. After the first hole, he bogeyed the next two. On the fourth hole the pin was in the back middle right, a really tough location, and Jack put a brilliant shot in there right of the hole. Geez if he doesn't three-putt that.

Lanny Wadkins: We were sort of hootin' and hollerin' in the locker room. We were getting a little rowdy at Jack's expense. We were going, "All right, when is Jack ever going to make a par?"

Tom Callahan: I was sitting next to Nelson Cullenward, a writer from San Francisco who was supposed to be a pretty good player, when Colbert came in to the interview area after his round. He had one of the better scores [72], but before he sat down I remember him pointing at Cullenward and saying, "I know how you play, Nelson, and there's no [expletive] way you could break 100 here today." And I remember Pat Fitzsimons talking to himself [after an 81]. It was like he was hallucinating. He said, "I thought I was the greatest player in the world. Boy, was I sheltered."

Sandy Tatum: The atmosphere after the first day was absolutely electric. It was as if somebody had dropped a bomb on the place. The media was very much on it; there was an element of virulent criticism. What really got to me was that they were questioning my motives. There were a lot of media people asking very provocative questions. It was not in a formal setting but in response to their allegations—"What are you trying to do, embarrass the best players in the world?"—that I came up with the reply, "No, we're trying to identify them."

Frank Hannigan (then the USGA assistant director, later executive director): I don't care what Sandy said or says, I loved seeing them humiliated. It was hilarious. I was stationed in the scoring tent at that time as players finished and signed their cards. I got an earful that week. Players vowed they would never come back. Most of them did.

AN ACCIDENT WAITING TO HAPPEN

Adding to the frenzy, word circulated that overnight before the second round a car had somehow been driven across the first green.

George Zahringer (2002 U.S. Mid-Amateur champion and member of the 2003 U.S. Walker Cup team): I had worked full-time on the Winged Foot greens crew in the summer of 1973, and the next year Ted Horton asked me to come back when I got out of school. My two tasks during the Open were to cut three or four greens in the morning, and then go with USGA officials to cut holes for the day's play. I drove out to cut the first green early Friday, and I see tire marks right down the center of the green. No question, these were automobile tire tracks. There was still a lot of dew on the grass, so it was easy to see. The tracks ran from the back of the green to the front, right down the middle. I went back and told Ted Horton, and we drove back out there with one of the USGA officials. They stood and watched me cut the green, and after I was done you would not have known that a car had driven across it. That's how firm and fast those greens were that week. Turned out, I could've cut that green without telling anyone, and no one would've ever known that a car had driven across it.

Sandy Tatum: I went out to investigate and could find no evidence on the green. I wasn't convinced it had happened.

George Zahringer: It clearly wasn't vandalism, because if someone wanted to damage the course they could've done a lot worse. I think what happened was someone who'd parked in the field between No. 8 on the [adjoining] East Course and No. 1 on the West Course had somehow gotten onto the service road that ran behind the first green. Maybe they'd had a few beers, or maybe not, but I think it was pure accident.

Dave Stockton: They put out a sign informing players there was damage to the first green, so I started to worry about it. Then we got down there, and it was perfect. You could have driven a tank across those greens and it wouldn't have hurt them.

George Zahringer: I don't remember if there were Stimp readings back then, but if I had to guess, I'd say they were rolling at 13 or 14 compared with today. We double-cut the greens by hand every morning and cut them with triplex mowers in the afternoon. It was a U.S. Open. It was supposed to be difficult.

Sandy Tatum: After setting up the golf course for the second day at the crack of dawn, I went back to the hotel and encountered a group of pros coming the other way heading to the course. One of them said, "Boy, Sandy, you look tired." And another of them said, "You'd be tired, too, if you were out all night waxing the greens on your hands and knees."

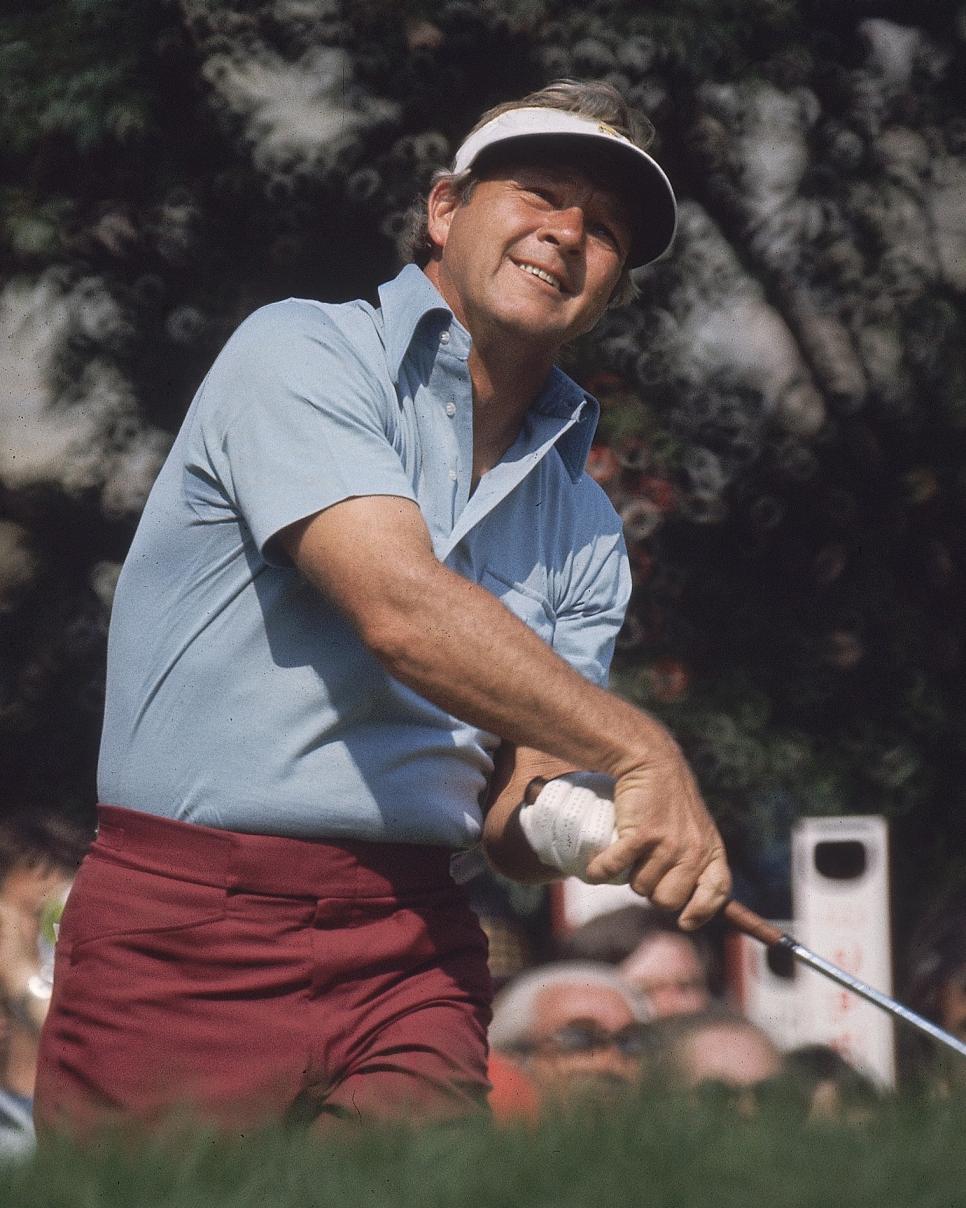

Tom Watson, the 54-hole leader, was disappointed with his collapse at Winged Foot, but got encouraging words from Byron Nelson.

John D. Hanlon

LAUGHING TO AVOID CRYING

Hubert Green bounced back from an 81 on Thursday to shoot 67, the tournament's low round and one of only seven sub-par rounds all week. Arnold Palmer, among others, moved into contention with a 70. The cut was a whopping 14-over-par 154 after 43 more rounds in the 80s.

Bill Erfurth (whose 88-84 was the highest score for anyone who finished 36 holes): That was the last Open I tried to qualify for. Played in five. I just wasn't a strong enough player. After Winged Foot, it was time for me to hang it up. I was embarrassed and took a lot of ribbing for my score. My good friend Bill Ogden [fellow Chicago-area club pro] starting calling me "Piano Keys." I didn't realize there were 88 keys on a piano.

Tom Watson: I remember finishing on Friday [at four over par, one shot off the lead] and going to the upstairs locker room. It was directly over the area where the 18th and 10th holes are located close together, and we saw the scoring standards going past with these huge scores. After 27 holes, guys were something like 28, 29 over par. We were just laughing. I was grateful to still be within shouting distance.

Andy Bean: I was a junior in college, hitting the ball really good and had a share of the lead after 26 holes; I'd birdied the fifth hole in the second round to tie for the lead. I hit my tee shot on 9, and it was cutting back across the fairway when a guy ran from the long rough across the fairway, and the ball just nailed him. I can still close my eyes and see the guy going down like he was shot; he kind of staggered and was sitting by a tree by the time I got there. His mouth was just crimson; I hope he had a good dental plan. Things like that happen on a golf course, and you wish you could block them out, but I couldn't and didn't. I guess it broke my concentration. I made a bogey or double bogey, and everything after that is just a blank. [Bean finished with a 76 before rounds of 83 and 81 left him a shot out of last place among those who made the cut.]

Jim Colbert: In the second round with Nicklaus, 14 or 15, we're both out there in the fairway. I was maybe three or four yards ahead of Jack. I'm sitting out there about 180 thinking I'm probably going to hit a 5-iron. He hits the ball, and it looks like a great shot, but that thing goes over the heads of the people behind the green. I hit my 5-iron on the green, a good shot. Jack said, "What did you hit?" I said, "Five-iron." He said, "Five-iron? That was 200 . . . oh, i added instead of sub- tracted.” This is Nicklaus, the guy who taught everybody about yardages. I'm thinking, Here's the greatest strategist of all time. I do that. He doesn't do that.

A 7 AT 7

Johnny Miller, the defending champion, was still in contention on Friday until he found the front-right bunker on the seventh hole and took four shots to get out, making a quadruple-bogey 7.

Johnny Miller: I kept trying to get cute with it; it was only a 25-foot bunker shot. I kept hitting the lip. I should have just taken my medicine, but I was a little stubborn back then.

Chris Mara: To this day I call that Johnny Miller's bunker. If I take a guest out to the club and he takes a couple shots to get out, I'll say, "You're two better than Johnny Miller."

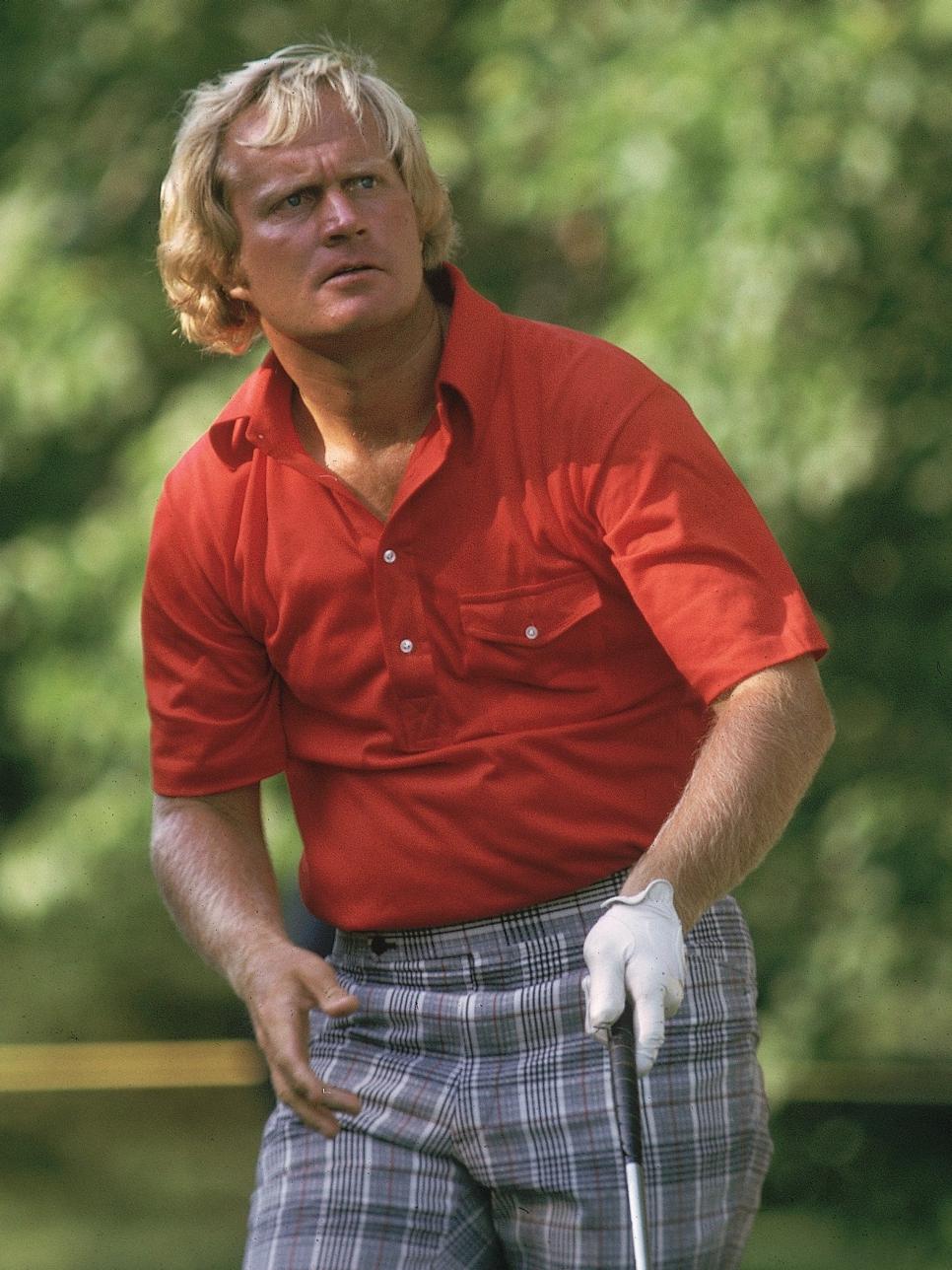

Arnold Palmer shared the 36-hole lead and much of the crowd of 17,000 followed him on Saturday.

James Drake

ARNOLD AND THE ARMY

After 36 holes, Arnold Palmer shared the lead of the United States Open. A crowd estimated at 17,000 converged on Winged Foot for the third round, and it seemed that most in the gallery followed Palmer and co-leader Gary Player. Irwin also had a share of the lead, and Watson was a stroke behind. Palmer struggled early before shooting a 73 to fall three strokes out of the lead, but Player shot himself out of it with a 77. Watson's 69 gave him a one-stroke lead over Irwin.

Jim Jennett (an ABC director): Our producer, Chuck Howard, thought the storyline was Arnold Palmer because the course was playing so difficult it would favor a more experienced player. I was involved with some of the early holes, and in those days I could feed him only two golfers at a time. I kept putting up Watson and Irwin, and he kept asking for Palmer, and I couldn't figure out why. He thought Arnold was going to snap out of it.

Arnold Palmer: My experience wasn't the rough so much as my putting let me down.

Jerry Tarde (editor, Golf Digest, and Winged Foot member): I'd just graduated high school and drove up from Philadelphia to see my first U.S. Open. I was positioned in the last row of the grandstand to the right of the 18th green the last day. When Palmer came through 10, I was able to stand up, turn around and see him hit his tee shot. A moment after I sat back down, there was this amazing eruption of cheers, and the grandstand literally shook. I stood up again to see what happened. "Arnie holed it for a 2," we heard. It was his last hurrah.

Sally Irwin: I was home in Frontenac [a St. Louis suburb], where we had recently moved, watching the tournament on TV with my 2½-year-old daughter, Becky, and surrounded by boxes. A 2½-year-old takes a lot of attention already. It was pretty intense trying to watch the golf as well.

Hale Irwin: I remember going to the last day and thinking, You've got a solid chance to win this thing, but you've got to avoid the costly mistake. I felt the best way to play aggressively was to putt 20 feet uphill rather than 10 feet downhill. Tom had his struggles during the day and was in the rough quite a bit.

Tom Watson: I was losing a lot of shots to the right, which was my Achilles' heel at the time, and you just couldn't play out of that rough. I was hacking it around. Made nine bogeys.

Dan Jenkins, Golf Digest columnist (then at Sports Illustrated): Watson wasn't Watson then, and he was labeled a choker after shooting 79.

Tom Watson: I didn't even think about that, didn't pay attention. If anything, it just made my resolve that much tougher. Sure, there was some heartbreak in losing at the time, but something good came of it. In the locker room afterward I was having a beer and commiserating with John Mahaffey. Byron Nelson approached me. There was a silence. Then he said he liked how I handled myself, liked my golf swing. "If you ever need any help with your game, give me a call." A couple of years later, I did. For Byron to come up and offer his services -- not his services, but his friendship -- has been a blessing to me and my career, my life.

Byron Nelson: I'd been around long enough to know how tough it would be on him. I approached him in the locker room upstairs. Tom was polite, but he was still a little upset in a way—not that he was acting up, but he didn't say much, even though he heard me. I remember him telling me later, "I wasn't in much of a mood to talk." I just told him, "If there's ever anything I can do for you, let me know," and it went from there. We built a good relationship that is still good. I don't get out to tournaments anymore at my age [94]. But we still talk to each other at least once a month.

Jim Colbert: The tour went to the American Golf Classic the next week, and I won in a four-man playoff. The tournament after that was the Western Open. When I walked into the locker room, I bumped into Watson. Tom's a Kansas City boy, just like me. I was headed toward the drinking fountain, and Watson said, "Great win, great win. Nice going." I said, "Yeah, I was pretty fortunate." He grabbed my arm and pulled me over to him and said, "Fortunate, my ass; you just gutted it out." Guess who won the tournament that week? Watson. He was out of the bag and running.

SCREAMS, BIRDIES AND PAR SAVES

Watson hadn't been alone in his troubles at Winged Foot. After rain ended earlier in the final round -- part of the reason the crowd was estimated at no more than 13,000 -- the West Course continued to assert itself, chopping away at the field.

Jay Haas (low amateur at 27-over-par 307): I played 72 holes and made only one birdie. I was pretty much out of my league at that stage. I had it in my head, if this is it, baby, I need to either really improve or find something else to do.

Bruce Summerhays (last among those who made the cut at 35-over-par 315): I was playing with Tom Shaw when a microburst of rain and wind came through. Tom scorched his drive on the ninth [a par 4 converted from a par 5 for the Open], hit a 3-wood second and couldn't reach the green with it. Somebody from the stands cried out, "Geez, I can shoot 25 over par." Tom just went ballistic. I thought he might go up in the stands to challenge the guy.

Jim Colbert: I was so angry and frustrated, after I signed my card I walked to the parking lot, got into my car and screamed for 15 minutes. I mean, I just screamed.

Jack Nicklaus (who shot a final-round 69): Obviously the golf course was tough. What, did seven over par win the tournament? You know it had to be conditions. Take 1965 and 1966, when I won the Masters both years. I shot 17 under in 1965, and I shot even par in 1966. Did the course change? No. It was just conditions. Did I think it was wrong? No. I didn't care; it was OK with me. I don't think I complained about it. I've always liked tougher conditions. It was fine. It just got away from them just a little bit."

Forrest Fezler: I hit a 1-iron 225 yards into the 12th green and two-putted for birdie [to go eight over par for the tournament, one shot off the eventual winning number]. Before that I was just trying to finish in the top 16 so I could get back in the Open and play in the Masters the following year. I didn't hit a green coming in, but I made some great saves on 15, 16 and 17.

Forrest Fezler is presented his check for finishing second to Hale Irwin.

Leonard Kamsler/Popperfoto

THE FINAL PUSH

Bogeys at the 15th and 16th pushed Irwin to seven over par, cutting the lead over Fezler to one stroke.

Forrest Fezler: I didn't realize Hale had bogeyed those two holes coming in until later that night. If I'd known, I might have been nervous.

Hale Irwin: I knew I was either in the lead or near the lead, but they didn't have leader boards all around like they do now. On 17 I drove it in the left rough, chopped it out and had a full wedge left. Put that in there maybe 12 feet and holed one of the best putts I ever had, broke about a foot and a half. A marshal told me that Fezler had bogeyed 18, but how does he know? I didn't know for a fact until I got down in the fairway after hitting my tee shot.

Jim Nantz (then 15 years old, now an announcer for CBS Sports and a Winged Foot member): That was my first major sporting event as a spectator; came up from the Jersey shore for the day with my dad. When Hale hit his tee shot on 18, we were off to the left side. I said to my dad, "We've got to get up there by the green'' to see the finish. One of my fondest memories as a kid is running those 300 yards so we could get in position to see the champion crowned.

Tom Watson: Hale hit the most pure 2-iron you've ever seen. Right over the flag. Just beautiful.

Hale Irwin said of his 1974 U.S. Open win: "I've come away bloodied, bruised and kicked, but I've enjoyed Winged Foot."

John D. Hanlon

VICTORY (AND REFLECTION)

A two-putt par from 20 feet clinched Irwin's two-stroke victory. The seven-over-par winning total remains the second-highest in an Open in more than half a century, matching Merion (1950), Oakland Hills (1951) and Olympic (1955) behind the weather-related nine-over-par 293 by Julius Boros at Brookline in 1963.

Peter McGarey: Hale told me afterward when it was getting frenzied to protect the clubs. Some of my friends hoisted me on their shoulders and carried me around in a victory lap like you would a coach or something.

Hale Irwin: I went back to the White Plains Hotel, and Dale Douglass and his wife were staying there. We celebrated by having room service in my room.

Sandy Tatum: It was a very satisfying result. Hale had the disposition to take the golf course as he found it and deal with it accordingly. A lot of players got so upset they were fighting the golf course instead of just taking it and dealing with it as Hale did.

Hale Irwin: I've come away bloodied, bruised and kicked, but I've enjoyed Winged Foot. It's been good to me. If you didn't come away from the West Course and feel you had been tested to the fullest, you were missing something.

I'd won twice prior to that. Winning was not an altogether unheard of thing. But Winged Foot was sort of a different beast. Emerging on the victorious side gave me an awful lot of credibility, but I've never been too worried about how the outside world considered me. That will come when I'm dead and gone.

Peter McGarey: I tell stories about that week all the time, and a lot of times guys say, "Yeah, right."

I spoke to Hale only one time after that week; it might've been the very next year in Arizona. I had him sign a copy of that book, Massacre at Winged Foot.

Bob Sommers (former USGA communications official): I'll never forgive Schaap for that. What massacre? The best player won.

Additional reporting by Craig Bestrom, Pete McDaniel and John Strege.