G-LO

George Lopez's improbable life is built on the power of memory. In sold-out arenas, he packs his stand-up act with dead-on details from a deprived Mexican-American childhood: the presumed curative powers of 7-Up ("Drink it all and then burp it up -- the cancer comes out"), a garden hose turning uneven patio cement into impromptu wading pools, a parent's impatient rejoinder to a plea to go to Chuck E. Cheese ("You want to see a mouse? Pull the refrigerator out!").

" 'Memmer?" Lopez asks the audience, the Spanglish inflection intensifying the nostalgia. "You 'memmer."

Lopez's past has made him, at 46, a major success: the star of an eponymous and now-syndicated sitcom, a headlining stand-up who has cable specials, movie roles and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. But that same past -- what he calls "my cycle of negativity" -- was also the source of insecurity, anger, depression, bouts of excessive drinking and ongoing therapy.

"Life is moments going by, but if you don't grab them, they're gone," he says in the dressing room after a recent show before more than 6,000 in San Jose, his husky tone and expression softer than the kinetic persona with which he commands a stage. "For a long time, the only moments that were available were bad ones. So now I make sure to grab the good ones."

He has done it in large part by turning his power of memory toward golf. "I relive my rounds all the time," Lopez says before recounting a special one that occurred on the par-5 12th hole at Poppy Hills during the second round of last year's AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am. "I was on this run of natural and net birdies. I hit my second shot into the woods, but against my caddie's advice, I decided to try to hit a pitching wedge over the trees. I caught it a little fat, but it got over, and when it hit the front edge of the green, it released. All I could see was the top of the flag, but as the ball kept rolling there was this crescendo from the gallery that exploded when it just missed the hole. I ran out of the trees with my arms up. When I pulled them down, I had to wipe my eyes because I was crying."

The tears came from the flip side of the reason he had so often wept as a child growing up in the gritty Los Angeles fringe town of Mission Hills. Lopez, who never knew his father and was abandoned by his mother at age 10, was usually rendered silent when his grandmother, a factory worker who became his chief guardian, would relentlessly ask him, "Why you crying?" The question would become the title of his autobiography and the recurring punch line in his 90-minute stand-up performances, Lopez portraying both his grandmother and young self as two people lost in the cycle of negativity.

But by the time Lopez emerged from the trees at Poppy Hills, the question had an answer.

"It hit me because that experience of people cheering, of succeeding, see, I never felt anything like that as a kid, and part of me is still starved for that," he says. "I was never encouraged or congratulated by anybody or included in anything. I didn't come from a home where people asked, "Did you have a good day?" or cared what I was doing or what I wanted to be. I fill some of that void with the laughs and adulation from doing comedy. But believe it or not, golf has fed me even more."

"George grew up an outsider, always excluded," says Ann Lopez, his wife of 14 years. "Golf gave him a true friend, a real sense of belonging, the only club he actually got to join. It's a positive place, and it gives him a place to be who he really is, deep down."

Since Lopez's first round, on a lonely Christmas Day in 1981 with rented clubs on an empty executive course, he has steadily immersed himself in the game. He's now an improving 10-handicapper who has played many of the world's great courses. The energy that will often lead to a 7 a.m. starting time after a stand-up gig that gets him to bed in the wee hours comes from the drive to improve himself.

Lopez is proud to take his journey public. He jumped at the chance to become, beginning last year, the first celebrity host of the Bob Hope Chrysler Classic since the founder's death in 2003. Lopez has turned his attention to bolstering the celebrity lineup, making mainstays out of friends like Samuel L. Jackson, Ray Romano, Joe Pesci, Andy Garcia, Huey Lewis and Cheech Marin and reaching out to new recruits like Clint Eastwood, Bill Clinton, Donald Trump and Catherine Zeta-Jones. Mostly he has raised the energy, installing an In-N-Out Burger stand on the practice tee that instantly became a lively gathering spot, making himself available for functions like a '70s-night party, throwing a dinner for the pros and tirelessly interacting with the on-course gallery.

"Bob Hope had it right," says Lopez. "He entertained the world and played golf, and brought the two together. I'm doing the same thing in my own way. You know, I respect and understand how a professional golfer needs to be focused and inward to perform. I'm the same before I go onstage. But I also think that's why golf needs entertainment now more than ever."

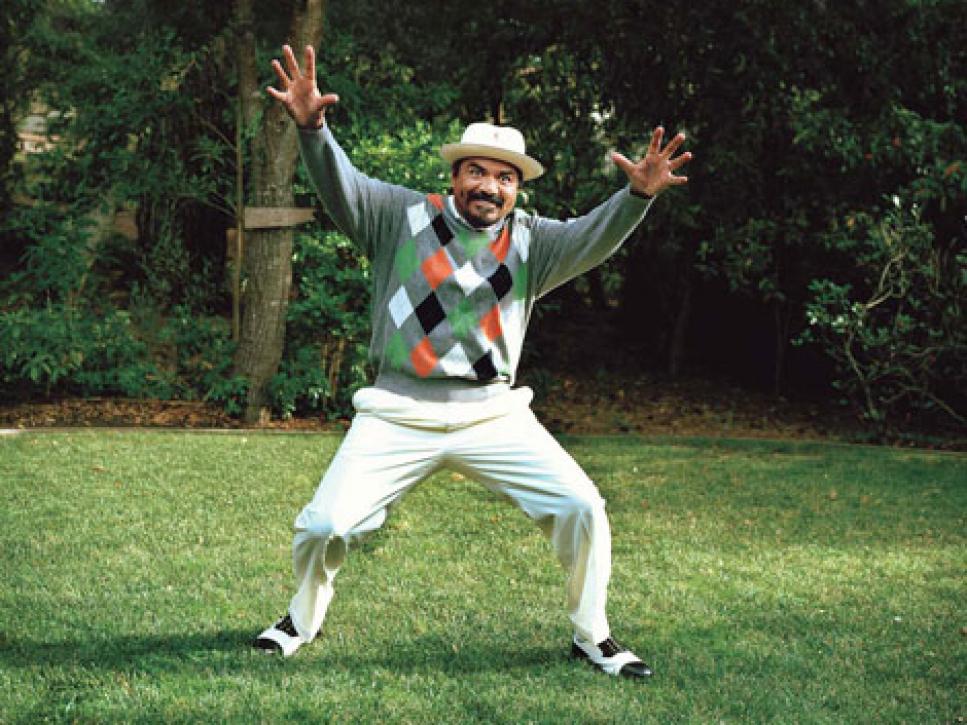

He has certainly provided it at the AT&T Pro-Am, raising a healthy debate about who is the bigger attraction, Lopez or longtime favorite Bill Murray. At Pebble Beach, where Lopez owns a home above the 15th tee, he pays tribute to the past. He wears vintage outfits featuring flowing trousers and cashmere sweaters in argyle.

"If I was the king of golf, I would make retro mandatory," he says. He recently paid $25,000 for the only known set of decanters that have commemorated each year of the tournament. "It represents the history of Bing and Bob and Phil Harris and all the times I wasn't there, all in one room," says Lopez who played his first AT&T in 2004.

He has continued to raise his golf profile, being out front on commercials and programs, teaming with David Feherty to host an annual charity tournament in Fort Worth, and forging strong friendships with pros Mike Weir and Vijay Singh (each of whom appear on the dedication list of one of Lopez's recent albums), as well as Lorena Ochoa, who also works for the cause of organ donation. (In 2005, Lopez, whose kidneys were removed because of a genetic disorder, was the recipient of a kidney donated by Ann.)

Away from crowds, Lopez plays mostly at one of Hope's old clubs, Lakeside, a minute from the Los Angeles home that serves as his base most of the year. In the approximately two months a year he spends in Pebble Beach, he plays nearly every day, making himself a more visible part of the community than the former mayor of Carmel, Eastwood. During recent rounds at Pebble and Spyglass, several onlookers waved to Lopez and offered pleasantries. "Always good to see you up here, George," said one well-accoutered matron. After the exchange, Lopez says, "You know, it means more for us, as Latinos, to be well-liked. Because we are not well-liked. All you have to do is watch CNN to see how Mexicans are regarded. And I know the golf community is conservative, but it just seems that on a golf course, people like each other."

Most important, golf has been the vehicle for Lopez to learn to like himself. "Golf is the father I never had," he says. "When I look at my 14 clubs, I think of each one of them as a teacher and role model. The long irons, they're like the strict teachers I had in school." He laughs. "I basically went through First Tee adult continuation school. If they had had it when I was a kid, I'd be the Christopher Columbus of The First Tee."

Golf would be natural fodder for Lopez's act, but he lays off.

"Somehow it doesn't feel right to me to make fun of it," he says. "Because it's so totally opposite to how I grew up, it's my cleansing thing. I always feel better after, no matter how bad I might play."

Has he ever heard that harshest of all terms for an entertainer from a minority background: sellout? "You know, it's never been viewed as, 'He's not one of us,' " Lopez says. "I think it's because people understand my journey wasn't an easy one."

Indeed, Lopez confesses that his formative years in the game were as poisoned by negativity as the rest of his life. "I threw clubs, buried them in the ground, snapped them and hated it," he says. "It was all part of the same thing. I was obsessed with other people's success, envious of other comedians, always wondering, Why not me? At the same time, because I didn't have any confidence, I wouldn't try for things, which must have made me angrier.

"Same thing in golf. I was always walking off the course. Then one time after I slammed the car door I looked in the mirror and had to admit it: Quitter, man. I realized I had become kind of a monster, and it was like I bottomed out. Something was telling me, anything that hurt that much had to be good. So I started to face things on the course and in my career and in my life. I decided that my experiences were valuable and authentic, not something to hide. That's when I found my comedic voice. And then the envy went away, the focus improved, the joy increased."

The peace is evident while playing with Lopez, though he can't help being funny. (Watching Bryan Kellen, the comedian who opens his show, struggle at Spyglass Hill, Lopez takes on the character of a suburban soccer dad, calling out, "It's OK, Bryan, we're your support system. Don't worry, everybody gets a trophy.") Lopez's overall demeanor is that of a subdued martial artist, gathering energy rather than expending it. "Golf is good air," he says at one point, taking in a deep breath. "I just let it in." Most notably, in 36 holes, Lopez never once shows a trace of agitation.

Although his full swing is long and stylish, the best part of Lopez's game is around the green. "Don't be afraid, Luke," he intones in the voice of Obi-Wan Kenobi while facing a fearsome downhill sand shot from a back bunker on Pebble Beach's fourth hole. He skims it expertly with a 58-degree wedge, leading to a remarkable par. A few holes later he flushes an iron approach, prompting him to comment, "I felt that in my chest. You know, in my soul."

Lopez finds inspiration in all corners of golf, with the biggest source of all being the close friendship he has developed the past few years with Lee Trevino. "There's no one I admire more than Lee," says Lopez. "To be Mexican-American at a time when our culture was really invisible, and to slay the best golfers in the world with a homemade, 'freehand' swing -- which is such a Mexican thing -- and for me to see that with the big eyes of a kid, as a lot of young kids connect success to Tiger, I connect my success to Lee. It turned out we both grew up knowing what it's like to be alone, we both learned how to mask some of that by being funny, and now to know him and love him, and have him love me more than anyone from my own upbringing, to have him call me 'My boy,' man, that's it."

"George found his niche with golf, and it gives him a purpose to live a good life," says Trevino. "I appreciate George. Some might say he was in the right place at the right time with his comedy. But George never gave up. I can tell that. He wanted to get out. And he kept working at it and working at it, and he did it. And see, I did the same thing. So we come from the same mold. With us, nothing has to be said. We know each other pretty well."

The journey seemed to culminate last fall when Lopez played St. Andrews for the first time.

"My wife gave me a book before we got married, Oh, the Places You'll Go!, by Dr. Seuss," says Lopez. "She was trying to tell me something, about what I was capable of, but I didn't get it. Over time, I've sort of lived the message in that book, and I couldn't have without what golf taught me. So I put it in my bag while I played the Old Course, and on the last hole when I posed on the Swilcan Bridge, I held it up.

"You know, I don't know how long this kidney is going to last," he says, now looking out over the Pacific from the 18th tee at Pebble. "So I just keep trying to collect great moments. That's why on as many days as possible, I play golf."

As he does, George Lopez is giving the game something it can remember.