News

John Merchant, African-American golf pioneer, dies at 87

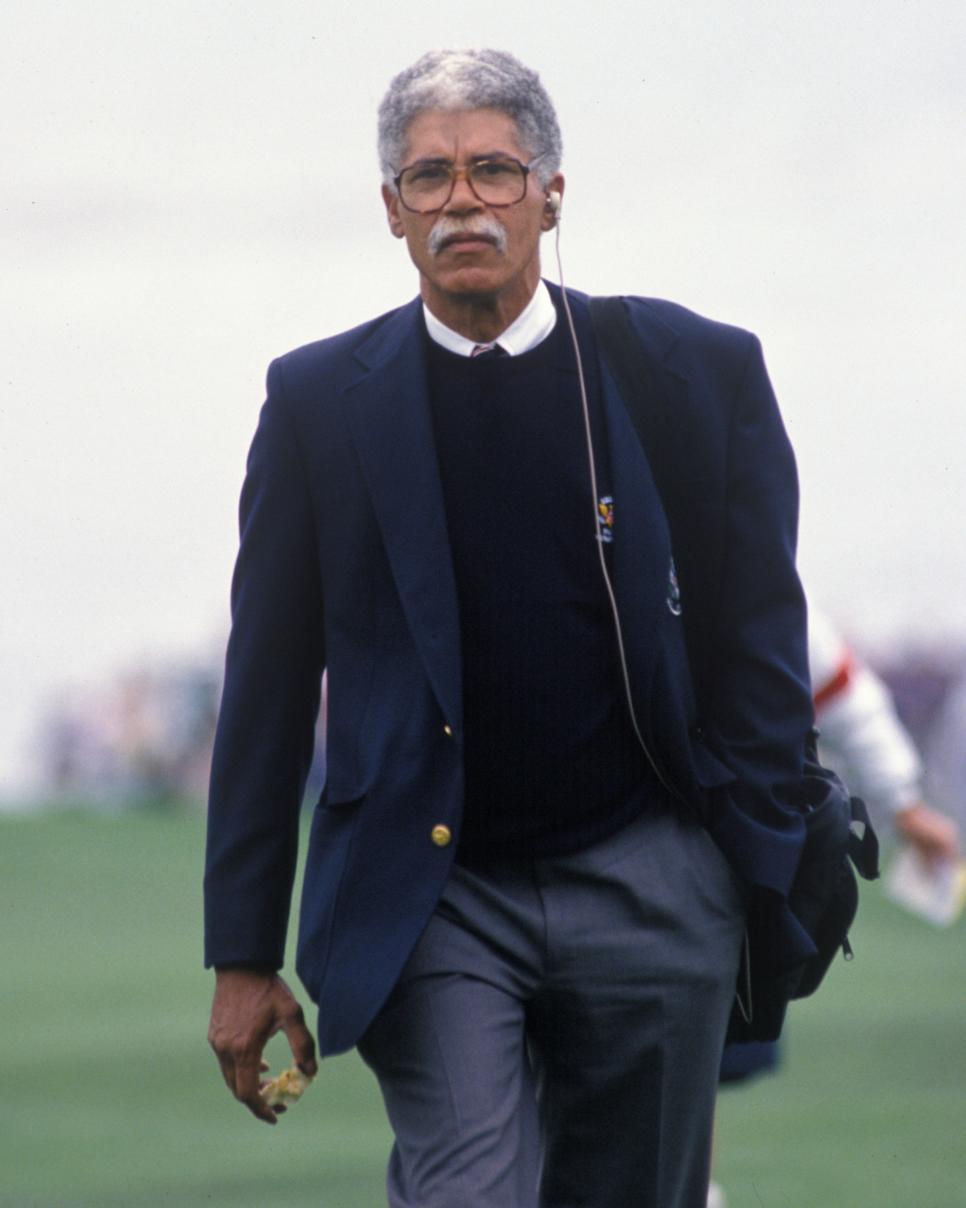

Copyright USGA Museum/Robert Walker

When I heard that John F. Merchant, the first African-American to serve on the USGA Executive Committee (not until 1992-’98), died at age 87, the moment that came to mind was a mix of elation and anger that seemed to sum up his complicated life.

It was in 1995, at the USGA’s centennial dinner in the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York—a celebration every bit as black-tie grand as it sounds. The USGA president, Reg Murphy, was making his keynote remarks and mentioned John Shippen as the first black man to play in the U.S. Open (1896). With that quiet reference, there was a loud BANG! from the audience, as John Merchant slammed his hand to the white-linen table and shouted, “IT’S ABOUT TIME!”

The outburst was shocking, and the event went on without any further incident, but I look back in wonder and some bemusement as it was such a perfect response.

American golf as an institution had ignored minorities for almost a century, and Merchant was symbolic of an overdue realization that we need to do better. Tiger Woods would rewrite the record book, but golf’s embrace of minorities and minorities' embrace of golf have been slow and uneven.

Merchant self-published an unvarnished autobiography in 2011 with the title, A Journey Worth Taking. He was the first black to graduate from the University of Virginia Law School, took up golf while in the U.S. Navy, set up a law practice in Connecticut and eventually became consumer counsel for the state.

He was a 7- or 8-handicap golfer with no administrative experience in the game when he was identified as a solution to the USGA’s problem in the wake of the Shoal Creek controversy, when the discriminatory policies of the PGA Championship site became public. I distinctly remember standing behind the ninth green at Hazeltine National during the 1991 U.S. Open when then USGA president Grant Spaeth walked by and happily announced, “We found one!” I had written an editorial in Golf Digest arguing that the USGA’s decision not to hold U.S. Opens at clubs without black members rung hollow when the organization didn’t have any African-Americans on its executive committee, and a nationwide search ensued.

Merchant turned out to be the one, when a well-connected attorney, Giles Payne, suggested him to Sandy Tatum, who was chairman of the USGA nominating committee. The first time I met with John in the Golf Digest offices, we agreed on a plan to hold the inaugural National Minority Golf Symposium, funded by the magazine.

In his book, Merchant wrote: “We agreed that there was value in encouraging people to meet and talk as a significant way to begin to seriously address the issue of diversity and build the bridges needed to span the gaps that existed, gaps fueled by misunderstanding, and embarrassing history, and an addiction to stereotypes.

“More importantly, we understood that achieving admirable diversity in the game was a huge challenge and would only happen over an extended period of time. No quick fix or immediate gratification should be expected because neither was even remotely available.”

Four annual conferences followed with Merchant as the chief organizer bringing together golf’s establishment and the leading African-American golfers in the country—including an ex-U.S. Army Special Forces named Earl Woods.

Merchant became executive director of the National Minority Golf Foundation and later was hired by Earl to represent his son, Tiger. It was Merchant who identified Hughes Norton of IMG as Tiger’s manager, assisted in the first Nike mega-endorsement deal and ushered Tiger from amateur to pro. In the end, John’s fiery style led to his dismissal from the minority symposium and Tiger’s employ, but his contribution to golf remains significant, lasting and not completely fulfilled.

Merchant had a strong belief that white golfers simply didn’t have black friends who played golf, and advancing civil rights in the game needed to be built on growing those friendships. It’s a journey worth taking, he said.