A Friend To The Giants Of The World

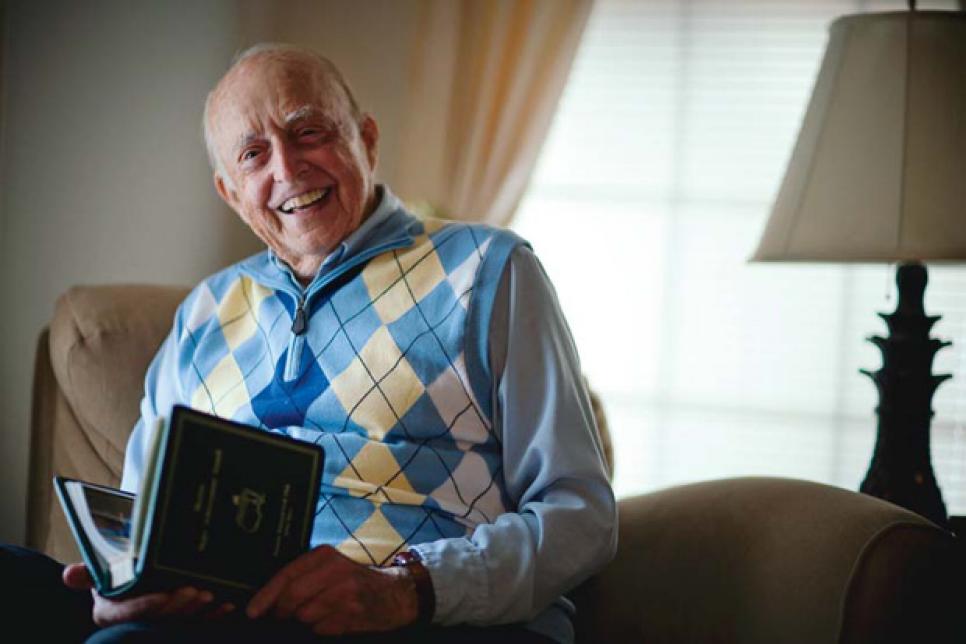

John Derr, 93, has stories on Gandhi, Einstein, Hogan and many more.

John Derr remembers the 1935 Masters

the same way he remembers everything. Vividly.

He recounts being a 17-year-old reporter for the Gaston Gazette in North Carolina

when he was seated next to O.B. Keeler in the press box of a Duke-Georgia Tech football game. Keeler, like so many, took a liking to Derr and urged him to come to "the Invitational at Bob's place" in April.

Six months later, Derr walked through the gates of Augusta National for the second Masters, and in the kind of kismet moment that has marked his life, immediately ran into Keeler. Who took him to the clubhouse to meet Bobby Jones, who introduced him to Grantland Rice, who introduced him to Clifford Roberts. Those relationships would lead to Derr being part of the first Masters telecast in 1956 as the announcer in the tower behind the 15th green, a post he would hold until 1982.

"There were only about 600 people there in '35, and I was in the clubhouse when Sarazen made his double eagle," Derr says from his home in Pinehurst, N.C. "When I told Gene I didn't see his shot, he said, 'That's interesting, because I've met 20,000 people who said they did.' "

Now 93, Derr endures as golf's living version of Zelig. Along with building fond relationships with sports giants from Ruth to Nicklaus -- and covering a record 62 Masters -- Derr had encounters with Gandhi, Einstein, Edison and Henry Ford. It's all chronicled in My Place at the Table, Derr's charming third book of reminiscences.

Derr was serving in India during World War II when, through a friendship with Gandhi's son, he was invited to the family's New Delhi home on numerous occasions. Years later, Derr saw Einstein on his daily walk along the Princeton golf course and asked the genius if he'd ever played the game. "I tried once," Einstein said. "Too complicated." As for Edison and Ford, in the 1920s they visited the Derr family farm to investigate uses of cottonseed oil. Derr, then 10, was already "announcing" the weddings and funerals of various farm animals.

"I've always been pretty relaxed around the mighty," he says. "I like people, and that usually leads to people liking you back. Now, a lot of folks build something around themselves, afraid to let anyone get to them. But with those types, it's often rewarding to break through."

He did so most notably with Roberts and Ben Hogan. "Cliff was not jolly," Derr says, "but in his gruff way he was enjoyable to be with." Derr got to know Hogan during the 1953 British Open at Carnoustie as the only American broadcaster there. "Ben let his guard down in a foreign country, and it led to a friendship," Derr says. "But Hogan was always a very sad man. I think he was even sad when he won."

Derr was closest to Sam Snead, sometimes rooming with him at tournaments. "Sam was, above all, honest, just the most open person," Derr says. "He was proud of his ability. Loved money, sex and dirty stories. Generous. Nowhere near dumb. He had some thoughts, and a lot of stories."

Sharing them has been Derr's greatest joy. At the Masters, his confidant was Lloyd Mangrum, who before his death in 1973 would meet Derr outside the clubhouse. "There we would do character assassinations," Derr says. "Not infrequently on ourselves."

One story involved Mangrum's wife calling his hotel room the week he won the 1946 U.S. Open. The phone was answered by another woman, who identified herself as Mrs. Mangrum. This led to the real Mrs. Mangrum quickly hailing a cab. Upon confronting her husband, she pulled a .45 pistol out of her purse and cried, "You worthless, no-good two-timer, I'm going to shoot you right here." To which Mangrum pleaded, "No, no, not now! Not when I'm playing so good!"

The laugh of golf's most prolific nonagenarian is interrupted by a thought. "You know," Derr says, "I've got to put that one in my next book."