News

Trampled Roots

Nick Price used to think he would retire to Zimbabwe after his playing career had ended, but he has given up that dream. Since 2000 he has only been back once to the country of his youth, the pain of seeing his homeland made unrecognizable by a ruthless dictator too much to bear.

"It's been so depressing since the land-grabbing started," says the Presidents Cup International team captain and former World No. 1. "Zimbabwe was successfully rebuilding interracial relationships, and the country was flourishing. Now, five million people [2008 figures] are starving. It's so sad, the most depressing thing I have ever seen."

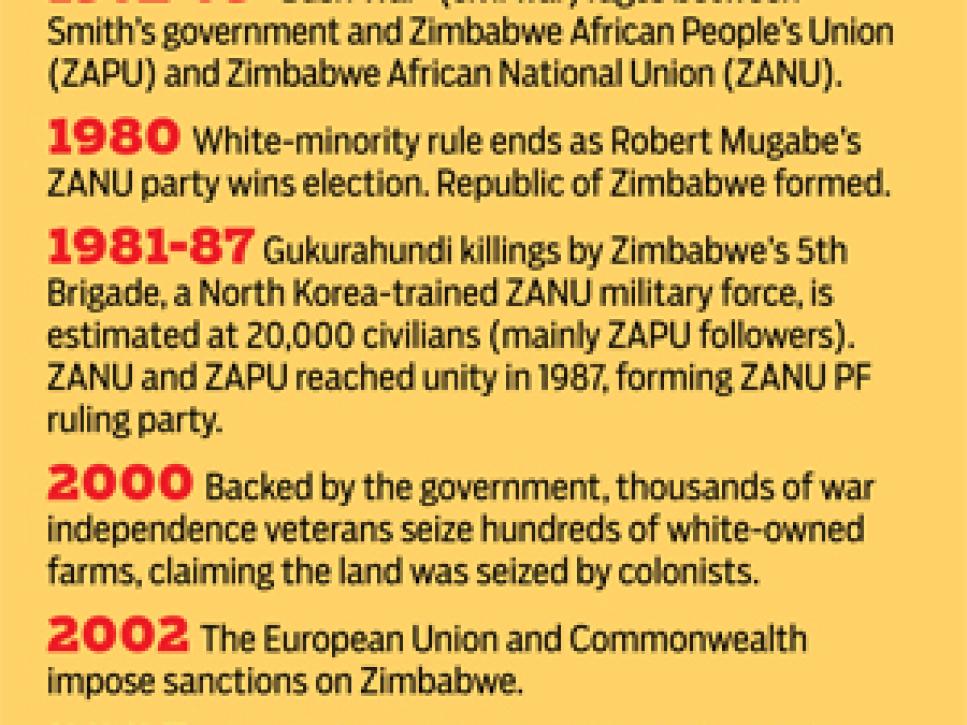

Thirty-three years have passed since white-minority rule ended in what was formerly Rhodesia. There was great hope for the new, independent nation called Zimbabwe, which elected Robert Mugabe, a former opposition leader against the government of Ian Smith, as its prime minister in 1980. But especially in the last decade the landlocked southern African country, about the size of Montana, has been on the brink of collapse. The now-president Mugabe's land-reform program, intended to alter the ethnic balance of land ownership after more than a century of British colonization, has resulted in often brutal farm seizures and displaced wealth. Along with sanctions imposed by the United States and other countries that condemn Mugabe's policies, Zimbabwe's citizens, 98 percent of whom are black, have endured economic meltdown, hyperinflation and elections scarred by violence.

Accompanying this chaos has been the dismantling of one of the finest golf environments ever seen. In the 1960s and '70s, even amid political upheaval from minority rule that caused the United States to impose trade sanctions on Rhodesia, the country was a golf Camelot. Located along the northeast border of South Africa, it featured brilliant weather, a large number of courses with affordable fees and active junior programs that would, for a few golden years, produce a disproportionate number of the world's finest players.

Three-time major champion Price, now 56, as well as his assistant captains, Mark McNulty, 59, and Tony Johnstone, 57, were products of this time. So were Denis Watson and renowned instructor David Leadbetter. "The weather was so good that you were outdoors 365 days a year, so we played everything," recalls Price. "My brother [Tim] bought a bag of clubs, not a set, a bag, completely mixed clubs. People say there wasn't hickory around in 1965 -- there was in Rhodesia! We didn't have access to new equipment because of sanctions, so we made the most of everything we had."

Clockwise from top left: an empty Warren Hills car park; the 10th at Warren Hills; Price with spoils in 1974, a photo of happier days in Warren Hills' clubhouse. Photos: Barry Havenga

On the school holidays, parents and volunteers ran junior programs every day of the week at different courses. Johnstone would travel 275 miles north from Bulawayo to Salisbury (Harare) and stay with Price or Watson. "We were issued a golf passport, a small blue book that kept a record of your handicap," explains Price. "You were taught from a young age about the rules, how to keep a scorecard and the correct etiquette. And boy, did we make sure the course was looked after. You never walked past an unraked bunker, because the juniors would definitely be blamed."

"Your handicap changed every day, so each holiday you had new goals -- breaking 80, breaking par, breaking 70 -- anything to get better," adds McNulty. "In our era there were five or six juniors that were better than us, but they went different ways after school. Maybe they didn't have the drive or the goals we had in golf." Competition was fierce across the vast pool of junior talent, yet played in a friendly spirit. Young Rhodesians were taught to respect the game and its traditions.

"We were just having fun. Life was simple," Price says. "We didn't know about professional golf until our mid-teens, because there was no live golf on TV. A month after Tony Jacklin won the 1969 British Open, a 32-millimeter film arrived at Warren Hills, which we watched in the clubhouse. A friend of mine's father bought Arnold Palmer's golf record -- a double LP of instruction and illustrations. We all crammed around the record player to listen to it."

When Golf World visited Warren Hills at noon on the Wednesday that Price chose compatriot Brendon de Jonge for the International Team, it was hard to believe it is the same club where Price and Leadbetter honed their skills as teenagers. A deserted parking lot, crestfallen clubhouse and scruffy-looking course were open, yet there was not a golfer to be seen. Meanwhile, at Royal Harare, a course that Price redesigned in 1997, a full field of 120 golfers was playing in a corporate outing.

"Royal has gained members from other clubs in Harare that were struggling to survive," says general manager Ian Mathieson. "For the few that can afford it, golfers are status-driven and want to be a member at a top club. We have 1,400 members who pay $900 annual subscription, which includes green fees." Rounds for visitors are $40 and the club does 38,000 rounds a year. A sleeve of three Titleist Pro V1 balls costs $24. Royal Harare has plenty of well water, enabling the course to look green in the dry Zimbabwe winters, and is fortuitously exempt from electricity blackouts thanks to its location opposite State House.

White and black golfers mix comfortably at golf clubs. Were it not for the black population taking to golf in the new millennium, the game would not have survived in Zimbabwe. Yet there has still been a sharp decline in the number of affiliated golfers (those belonging to a club) during the last 10 years -- from approximately 7,500 in 2004 to just 3,000.

"Golf is very much a luxury in Zim," says Roger Baylis, head professional at Chapman GC in Harare and national coach for the Zimbabwe Golf Association. "With the exorbitant cost of living, disposable income for golf only comes after everything else has been paid for. There must have been close to 100 golf courses in Zimbabwe in the 1990s -- not all 18-holers of course -- but I estimate that we have lost about 60 clubs. Golf has suffered most in the rural areas."

Evidence of this lies in ruin 30 miles south of Zimbabwe's capital at Harare South GC. Once regarded as a top-five course in the country, the layout is now overgrown and unrecognizable as a golf course to the steady traffic that passes by on an adjacent interstate road. Harare South began its decline when farmers who supported the club were forced off their land.

Tim Price, Nick's older brother, tried in vain to keep Harare South going before he succumbed to cancer in 2010 at age 60. The vast clubhouse still stands, but when a visitor asked to look around the rest of the deserted property, a stern refusal was delivered from the only person encountered. Independence war veterans are alleged to have occupied the clubhouse.

The Zimbabwean government now faces criticism from a growing number of young black people desperate for change in their country, where more than 14 percent of its 13 million people live with HIV/AIDS, and life expectancy in 2012 was just 50 for men and 47 for women.

"I went in search of the Zimbabwe I knew, and it was a shock: power cuts, water cuts, potholes down the streets, and 80 percent of the population not working," NoViolet Bulawayo told The Guardian newspaper in the United Kingdom in early September. The 31-year-old's debut novel about her homeland, We Need New Names, is short-listed for the 2013 Man Booker Prize.

Bulawayo (real name Elizabeth Tshele) emigrated to the U.S. at 18, returning home for the first time in April. "I knew from news and stories that things were hard, but being there and seeing it for myself was just heart-breaking," she said. "Even now knowing that there are no answers, and it's not going to get better any time so on, is crushing."

The Zimbabwean Presidents Cup captains unanimously agree that their compulsory one-year military training after high school helped them in their professional careers. Although Price (Air Force) and McNulty and Johnstone (Army) were kept away from the front line of the Rhodesian Bush War, the trio admit that the discipline of military training helped them develop strict practice regimens, resulting in the enhanced ability to work on their games for very long periods. The guerrilla war raged from 1972-79 between the government and two opposing factions, Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU).

"Sportsmen were highly revered in Rhodesia, so if anything happened to them in the war, it would have been very bad for morale," says Price, who worked radio signals in 1976. "We all felt like we wanted to do more and join our friends in the action. I did get shot at, though, and had mortars land nearby, so golf was far away at that stage. We didn't necessarily agree with everything that was going on, but in those days you did as you were told."

Price's tone changes noticeably when asked about his last visit to his homeland. In 2003 Price told Golf Digest he had not been "home" for three years and had been subdued in his criticism of the government for fear of reprisals to his extended family. In 2007 the Price family slipped into Zimbabwe for a vacation.

"I wanted my kids to experience the bush, to see a little bit of what I had growing up," says a subdued Price. "We spent two weeks traveling around safari parks and visited the Victoria Falls, but we didn't go to Harare. I didn't want to see how badly things had deteriorated there. We saw wild animals that had been poached and snared -- but people were starving in the height of inflation, so you can understand the desperation they faced.

"Zimbabwe was a country that was starting to flourish in the 1990s, with a massive opportunity to move forward in the new millennium," Price says. "We were a major exporter of maize and wheat to the rest of Africa and one of the largest tobacco producers in the world. I never wanted Rhodesia back; I wanted a unified country back. White farmers learned the African languages, and people treated each other with respect. Everyone was making a huge effort."

Backed by the government, thousands of war independence veterans began invading hundreds of white-owned farms in 2000, claiming colonists had previously seized the land. But the people who took over the farms did not have the skills or education to farm productively, and the farming industry began a rapid decline. "What a lot of people don't know is that many of the white farmers who were invaded had bought their land after independence in 1980," explains Price.

Price and Johnstone didn't come from farming stock, but McNulty's family was forced off their land in 2002. They farmed tobacco, cattle and blue maize 70 miles north of Harare near the town of Centenary. McNulty had a rural upbringing and honed his famed putting stroke on sand greens at Centenary CC, where his mother served on the committee.

"My family was lucky not to have faced any violence when the war veterans came for the farm," says McNulty. "I can't say that they were respectful, but [my relatives] weren't harmed. Others were not as fortunate. We knew people who were killed because they stood their ground. I was never hesitant to return to Zimbabwe, but I was angry and did stay away in the mid-2000s." McNulty took up Irish citizenship in 2003 (through a maternal grandmother) because he could not renew his Zimbabwean passport as a non-resident.

Johnstone, who plays the European Senior Tour and works for Sky Sports in the United Kingdom as a golf analyst, still considers himself a Zimbabwean but travels on a British passport after his Zim passport was stolen. "It's an absolute travesty what has happened in Zimbabwe, and worst of all the world just looks on," says Johnstone. "Zim used to be known as the breadbasket of Africa -- now it's the basket-case of the continent. But I still go back for two weeks every year. It's very painful to see my country's downfall, but it's my homeland and I love spending time in the bush [on safari]."

Johnstone is like many tourists to Zimbabwe who seldom feel their safety is threatened despite the "high risk/extreme risk" security notification issued by authorities to potential travelers.

As Price and McNulty began contemplating Champions Tour careers, Zimbabwe needed new talent to continue the country's golf legacy into the new millennium, and they found it in Lewis Chitengwa, who was a perfect representation of the country's demographics. It's easy to miss the Lewis Muridzo Chitengwa Golf Academy at Wingate Park GC, where Lewis Chitengwa Sr. teaches the game. It consists of a forlorn one-room building behind the practice tee, where Chitengwa Sr. has taught juniors and Wingate members for the last 30 years, including de Jonge, now 33, from age 5.

In 1992 the younger Chitengwa defeated Tiger Woods head-to-head in the final round of the Orange Bowl junior championship, and a year later became the first black golfer to win the South African Amateur Championship. A two-time All-American college career followed at Virginia before he turned pro.

But in 2001, only 26, Chitengwa died in tragic circumstances. Showing flu-like symptoms after the second round of the Canadian Tour's Edmonton Open, Chitengwa Jr. slipped into a coma and died from a rare and deadly form of meningitis. "I guarantee you, he would have been a tournament winner on the PGA Tour," Price told Golf Digest following Chitengwa Jr.'s death. "He had determination and intensity, and he had a great short game. Guys with great short games win golf tournaments."

Lewis Sr. invited Golf World into his self-described dilapidated house, 150 yards from the academy at Wingate. The Orange Bowl trophies sit proudly in the home, but the family is suffering financially due to golf's decline in Zimbabwe. Lewis Sr. and wife Josephine are understandably reluctant to comment on the Mugabe regime, opting to cling to the hope that life will start to improve for their embattled homeland.

Despite the best efforts of Baylis and Chitengwa Sr., promising Zimbabwean golfers are now forced to go the U.S. collegiate route to progress in amateur golf. Current Zimbabwean talent on scholarships includes Scott Vincent (a junior at Virginia Tech), Ray Badenhorst and Brett Krog (Florida Tech, a junior and sophomore, respectively) and Ben Follet-Smith (Mississippi State, freshman).

"I'm cynical and pessimistic about my country now," Price says. "Mugabe has such a lock on power that it will take a long time to get some form of prosperity back, even after he is gone. My generation bore the brunt of both the [Ian] Smith and Mugabe ideologies. I lost friends and acquaintances in a war that I didn't totally agree with. But my dad and two brothers are buried there, and I was very proud to represent my country on the world stage, especially when we played together as a team at the World Cup and Dunhill Cup."

Price wishes he could have given back more to golf in Zimbabwe, considering the huge pool of talent that still exists among the youth. "There are probably 100 kids with the athletic ability of Tiger Woods in my country," he says excitedly. Perhaps he will be able to contribute to the rebuilding of his country one day. Despite the daily rigors of living, there is still an overall sentiment of hope and aspiration among a resilient people.

It may take a political regime change or intervention from a foreign power to avoid more golf clubs disintegrating into the African landscape, but for now, the kids who swing away freely on Lewis Chitengwa Sr.'s practice range can still dream of emulating the names they see on the honor boards within Zimbabwean clubhouses.

Barry Havenga is the assistant editor of Golf Digest South Africa.