News

Talking A Good Game

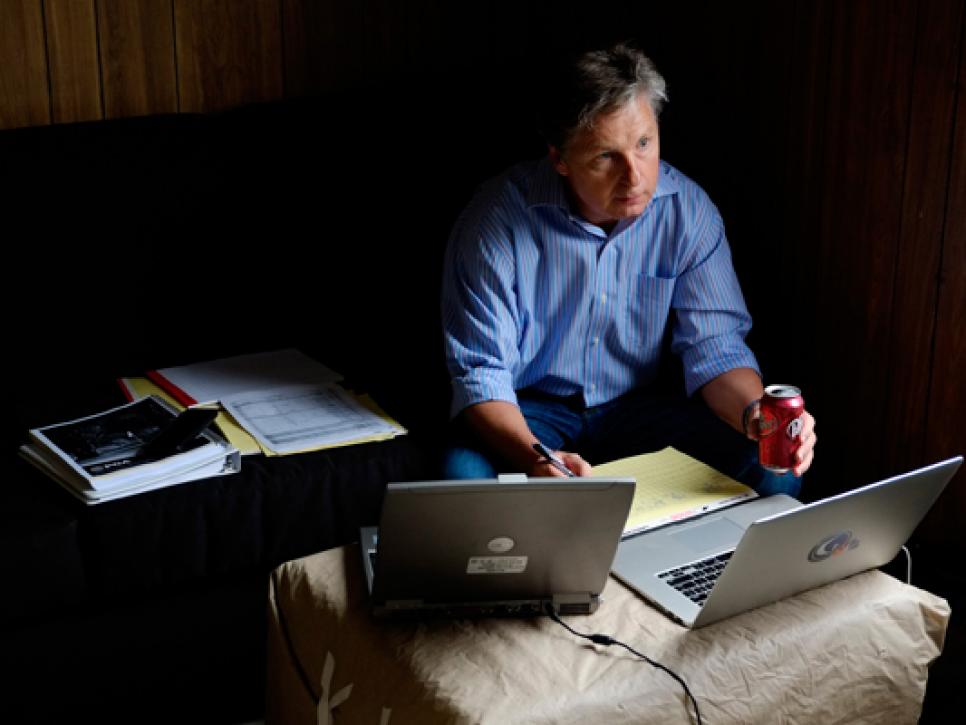

Analyze this: Isenhour, who last competed on tour in 2009, playfully rebuffs GC host Ryan Burr.

In his former life as a player, Tripp Isenhour's day would be ending at 6 p.m. during Thursday of tournament week. Now it is just beginning in his new life as an analyst for Golf Channel.

Preparation means sitting in a chair and allowing a stylist to make him look just right for an evening of TV duty. She applies makeup on Isenhour's face and finishes it off with a few brushes of powder. Finally, she pats down some wayward strains of hair, as Isenhour, oblivious to the primping, goes over his notes.

Eventually released from the beauty portion of his night, he takes the short walk into the Golf Channel studio and confers with a producer. In a few moments, he sits in another chair, this one on the set for "The Grey Goose 19th Hole."

The twice-weekly show calls for Isenhour, who had a 12-year career on the PGA and Web.com Tours, to offer fresh and candid insights about all things golf, especially on the PGA Tour. When the taping ends around 9:30 p.m., a content Isenhour is ready to call it a day. No visit to the scorer's tent for him.

"The only question players ask me now is, 'Do you like your new gig?' " Isenhour says. "I say, 'Yeah, I don't have to make four-footers, and I still get paid.' "

Isenhour, who last played competitively in 2009, is among the group of former players (and in some cases part-time current players) who have found a second life as golf analysts on TV and radio. And the number is likely to grow. "We're talking to people all the time," says Golf Channel president Mike McCarley.

The demand for analysts is greater because Golf Channel is constantly expanding its coverage, and other platforms are emerging too. Yet a different dynamic is at work compared to what often transpires in other sports.

For the most part, these golf analyst jobs are being filled by former players such as Isenhour and others who don't have the cachet of having Hall of Fame résumés as players. They are, for lack of a better phrase, journeymen pros, who now are viewed as experts when it comes to dissecting the work of Tiger, Phil and Rory.

Besides Isenhour, who never won on the PGA Tour, Golf Channel's roster of studio analysts includes Brandel Chamblee, Frank Nobilo, Charlie Rymer, Steve Flesch and Notah Begay III. John Maginnes has emerged as a major presence for PGA Tour Radio. Combined number of major-championship victories: zero.

Compare that to the group of studio analysts for the NFL Network: Hall of Famers Deion Sanders, Marshall Faulk, Michael Irvin, Warren Sapp and a likely future enshrinee, Kurt Warner. Charles Barkley and Magic Johnson do high-profile studio work in basketball; Terry Bradshaw, one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time, has become an even bigger star during his years on Fox NFL Sunday.

The difference, of course, is that professional golf is the only sport in which the top stars seem to play forever. While a football player's career is done by his early- to mid-30s if he is lucky to last that long, elite golfers play well into their 40s on the PGA Tour and most make a seamless transition to the Champions Tour in their 50s.

As a result, the roster of available big-name talent for TV is much slimmer, or nonexistent, for Molly Solomon, Golf Channel's executive producer. "It's difficult because golfers never want to quit," Solomon says. "Once they get to 50, another door opens for them. It's hard to get them to commit to TV. Why would you want to work for a living?"

There are golfers, however, for whom playing the tour didn't turn into a lifetime profession. When Rymer turned pro after finishing at Georgia Tech in 1991, he thought, "This is what I'm going to do the rest of my life."

It came to an abrupt end for him in the late '90s after spending only three years on the PGA Tour. Despite a handful of top finishes, Rymer realized it wasn't going to be his life's work. Plan B materialized while he was hitting balls next to CBS' Gary McCord prior to an outing in April 1998.

"He said, 'You ought to do TV,' " Rymer remembers. "I said, 'I'm not qualified.' He said, 'You're an idiot. That makes you qualified to do TV.' " McCord made some calls on Rymer's behalf, and it led to him launching a broadcast career at ESPN; he made the move to the Golf Channel in 2009.

Persistent back problems brought Begay to the crossroads last year. The four-time PGA Tour winner had done some work for Golf Channel while playing a limited schedule without much success. With the departure of Dottie Pepper, NBC golf producer Tommy Roy and McCarley wanted to hire Begay as a full-time on-course reporter.

Begay, though, wanted to take one final shot at Q school last fall. Roy and McCarley weren't rooting against Begay, but they weren't disappointed when he didn't regain his card. "The day after Notah was out at Q school, Tommy was on the phone and said, 'Can we call him now?' " McCarley says. "Notah had shown some real promise when he did the studio."

A deal with NBC/Golf Channel was done within a week. At age 40, Begay knew it was time. "A player gets to the point where you have to make a fair and honest assessment of your performance," Begay says. "I was spending more money to play than I was making. Not making it through Q school was the final nail in the coffin."

Flesch, meanwhile, has found himself in limbo. At 46, he is trying to play part-time on the PGA Tour -- he has limited status in 2013 -- with an eye toward the Champions Tour at 50 while analyzing the game for Golf Channel. The arrangement produced an odd scenario for Flesch earlier this year. A second-round 64 put him in contention during the Colonial, where he finished T-22 after a closing 73. The following week he was inside the ropes again, this time as an on-course reporter for Golf Channel's Memorial coverage.

"I will say, TV is infinitely less stressful," Flesch says.

However, broadcasting isn't without its challenges. Begay realized just how much things had changed in his life when he arrived to work his first tournament for TV and couldn't find the production compound. "As a player, we're used to driving up Magnolia Lane in our tournament cars," Begay said. "Now, in TV, we enter through a back gate."

The transition from player to analyst happens quickly, without time to go to broadcast school to learn the basics. Isenhour had little idea of what to do when he worked his first tournament in 2011. He figured he didn't screw up because he got asked to do another one.

On-the-job training comes quickly. "There's a pretty high learning curve," Begay says. "It's everything from diction and grammar to working with the camera and where to stand. You have get used to people talking in your ear while you're talking. It's even as basic as, 'Sit up straight.' "

Most new analysts can master posture. It is the main requirement that presents the ultimate challenge: You must have something compelling to say.

McCarley and Solomon have seen plenty of would-be analysts in many sports, including major stars, miss the cut. "You've got to have an opinion. You can't say, 'I'm not sure,' " Solomon says. " 'I'm not sure' doesn't make for interesting TV."

Chamblee has emerged as Golf Channel's most important player when it comes to interesting TV. After a 14-year career which included one PGA Tour title, he made the transition to the Golf Channel in 2004. He separated himself by voicing blunt opinions backed by an endless stream of facts, virtually all of which he researches himself.

Then Chamblee digs in and dares someone to take him on. He has a strong, almost bulldog, mentality when making his point. McCarley says, "He probably should have been a trial attorney."

In a sport where analysts often tread lightly, Chamblee's content and presentation are unique. "You have to realize you're not speaking to the golf professionals," Chamblee says. "That's a small audience. There are 50 million golfers. You're trying to explain to them why something happened. Not only is this a job, it's a responsibility. It's a responsibility to not state the obvious. It's to enlighten the viewer."

His outspoken views haven't always made him a favorite among members of his former fraternity. Flesch, though, gives Chamblee high marks for not dodging his critics.

"One of the things about Brandel that gives me the ultimate respect is that if he throws out an opinion, the very next day he's on the practice tee," Flesch says. "He's accessible. If you have a problem, you can find him. I can't say that for other analysts out there."

Chamblee has shown you don't have to be a major winner to become a major TV golf presence. His insightful commentary is firmly in the tradition of former role players or backups in other sports who had to study their games hard to persevere on the field or court before bringing their smarts and savvy to successful broadcasting careers.

Having not reached the competitive pinnacle is a reality for many of the golf analysts who don't speak from experience when critiquing big stars in the biggest events. Flesch admits he can't talk about feeling the pressure of being the leader on the 72nd hole of a major because "I've never walked in those shoes," and believes the playing achievements of announcers Nick Faldo and Johnny Miller "add weight to their analysis." The gap is even more profound for analysts like Rymer and Isenhour, who contended but never won on the PGA Tour. What kind of credibility do they have in assessing someone like Tiger Woods in a major?

"From my standpoint, I know what Tiger Woods is doing because I was trying to do the same thing," Isenhour contends. "It made me more aware of what goes into making Tiger Woods, maybe even more than he's aware of himself. I couldn't do it, and it was frustrating. But I also came to understand what the best players were doing. I come at it from that perspective."

Rymer jokes that he has his "Ph.D in golf." However, he doesn't pretend to be something he's not. "I'm not going to make statements I'm not qualified to make," he says. "I'm not going to try to get inside a major champion's head. I'll talk about how I'd feel if I was in that situation. I try to be really honest about that. I understand my place in the game. I don't want to walk in a locker room and have Tiger Woods say, 'Why did you talk about that? You never did that.' "

Begay understands that if he doesn't offer honest appraisals of his former peers, he won't have a TV job for long. But he isn't reckless. "Players don't like to get criticized. I know that," he says. "I always follow a simple rule: I won't say something on TV that I wouldn't tell them to their face."

The odds of marquee stars stepping into an analyst's seat on a regular basis in the future seem remote. Besides the long-term option of the Champions Tour, those players likely won't have the financial incentive to go into TV. "Fred Couples isn't coming in five hours early to prep for a show," Rymer says.

Rymer does, rising at 3 a.m. to do Golf Channel's "Morning Drive." While the network won't disclose financial figures, according to sources, salaries are in six figures for analysts such as Rymer and Isenhour, with outside opportunities to supplement their income with appearances thanks to their TV exposure. Chamblee's endorsements likely put him well beyond the $1 million mark.

For these analysts it is a way to make a nice living and stay connected to the game. Current players with similar career paths might be tempted to follow suit this fall. The elimination of Q school means some players will have only the Web.com Tour if they want to continue playing. It won't be an enticing option for pros who have spent years on the PGA Tour.

"That's a brand-new decision point," says McCarley, who expects his phone to start ringing with new prospects.

Some of them, no doubt, will have reached a fork in their professional lives as Isenhour did. He missed a putt on the 72nd hole of the 2007 Honda Classic that would have put him in a playoff. The following week, his back flared up. He was never the same and soon off the tour.

"I never envisioned something like this," Isenhour says of his second act. "I guess everything happens for a reason."

Being an analyst has given him a golf education unavailable before becoming a paid observer. As with other players-turned-announcers -- Jim Colbert, for one, credited TV work as an essential prelude to a superb senior record that eclipsed his PGA Tour career -- he now can see what he was lacking as a golfer. "Would I have been a better player? Absolutely," Isenhour says of the knowledge he has gleaned. "The best players don't have situational confidence. They have unshakable day-to-day confidence in their abilities. Bad shots don't make them change their golf swing or approach. I let situations determine my confidence."

Unlike Flesch, Isenhour, 45, isn't counting the days until he is eligible for the Champions Tour. He is very content to make a living talking about golf. "My golf now is beer and cigars," he says. "My attitude is that when I hit a bad shot, it doesn't bother me at all. I like it that way."

Not that all the second-guessing stops. Television has been Rymer's life for 15 years, much longer than he played professionally, yet some things endure.

"I can't imagine a job more rewarding, but also a job that kicks you in the butt as much as TV," Rymer says. "And doing live TV, everyone you work with cares about it so much -- you're motivated to be good. It's like a round of golf. If you shoot a 65, you think it should have been 64. You never achieve perfection. You always think you can do better."

In other words, despite trading a lob wedge for a lavalier mic and sunscreen for face powder, the game remains the same.