News

Ranking Gives Norman His Due

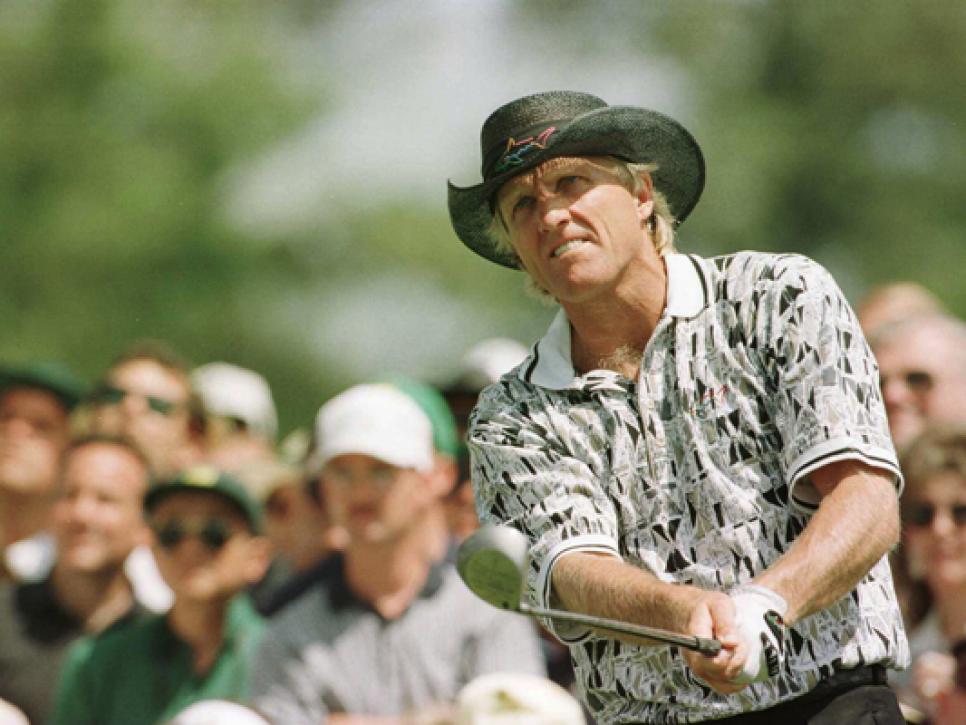

Greg Norman during the final round of the 1996 Masters.

The enduring criticism of Greg Norman is that he too often finished second -- 31 times against 20 wins on the PGA Tour, including eight particularly painful runners-up along with two wins in majors. It was the most in each category by any player in our Golf World Modern 100 (page 34) for the period beginning in 1980.

But Norman was genuinely gratified by his latest runner-up -- finishing No. 2 to Tiger Woods in our ranking. When informed of the details last week, his face gave off the relieved "thank you" of a person who has been waiting a long time to finally be defended.

"It feels good," he said. "First of all, no one else can do what Tiger's done. But to finish second with all those other names behind me, to be better rated from a pure results standpoint than maybe I have been in other ways, damn right it feels good."

No doubt it will surprise some that after Woods, the golfer who performed at the highest level over the last 34 years, was Norman. Between his failures down the stretch in majors and the backlash from his highly marketed Great White Shark image, it has been common in recent years to hear Norman characterized as overrated. But our numbers prove that Norman in his prime was a better player week in and week out than everyone but Woods.

It shouldn't be forgotten that Norman's "good" was awesome. His record 63 during the 1986 British Open at Turnberry, which included three-putting the final hole from 28 feet, occurred on a day when only 15 players broke par. It was the same year Norman achieved the so-called Saturday Slam, leading all four majors after 54 holes, a Pyrrhic tour de force almost as distinctive as the Tiger Slam.

For all the flashes of brilliance, like going 24 under at the 1994 Players Championship, the core of Norman's quality was his rare-air consistency. He was "there" more often than any of his contemporaries, reflected in his 331 weeks at No. 1 on the Official World Golf Ranking, a span second only to Woods' and far ahead of Nick Faldo's 97 weeks and Seve Ballesteros' 61.

Norman's numbers against everyone else's on the PGA Tour since 1980 don't lie. His percentage of top-10 finishes in eligible seasons for our Modern 100 was 47.7 percent, behind only Woods' phenomenal 63.6 percent. He was also second to Woods in the bottom-line category of average stroke differential, his 1.954 figure over 262 starts meaning he beat the field's average score by nearly two strokes a day. And to the criticism that Norman was a poor closer, his final-round stroke differential of 1.701 ranked third behind Woods and Jack Nicklaus. As for missed cuts, Norman had the lowest percentage -- 7.6 percent -- other than Woods.

Those telling statistics are why Norman edged Phil Mickelson on our ranking, despite Mickelson's record of 42 victories and five majors. But while Mickelson was better at capitalizing on his "good," his week-to-week play compared to Norman's has been hit or miss. Mickelson ranked ninth in top-10 percentage, 14th in overall average stroke differential and a surprising 31st in that category for final rounds. He was 13th in fewest missed cuts with a percentage of 13.9.

Many will argue that Mickelson compiling a win record that is essentially twice Norman's should trump all other factors. Fair enough, but if that's the case, Norman's international record during this period should at least be part of the discussion. He has 45 victories away from the PGA Tour, while Mickelson has three.

The Shark's cross to bear will always be his inefficiency at closing out majors. That weakness was most pronounced in contrast to the opportunistic Faldo, who won six majors in the same time frame. Faldo's golf was arguably more nuanced than Norman's -- he possessed more precision with the irons and better judgment under pressure. In four of his major victories he was the beneficiary of late blunders by other players in a way that Norman never seemed to be. Faldo seemed to have Norman's number head to head, and it is the indelible memory of the Englishman's cold resolve against the Aussie's shakiness in the agonizing final round of the 1996 Masters that continues to inflict the most damage to Norman's legacy.

Still, our metrics prove Norman had more game than Faldo (who was 10th in our ranking), and in fact, since 1980, more game than everyone but Woods. And that's not just another consolation prize for a player who had too many. It's an overdue validation of greatness.