News

Memory Lane

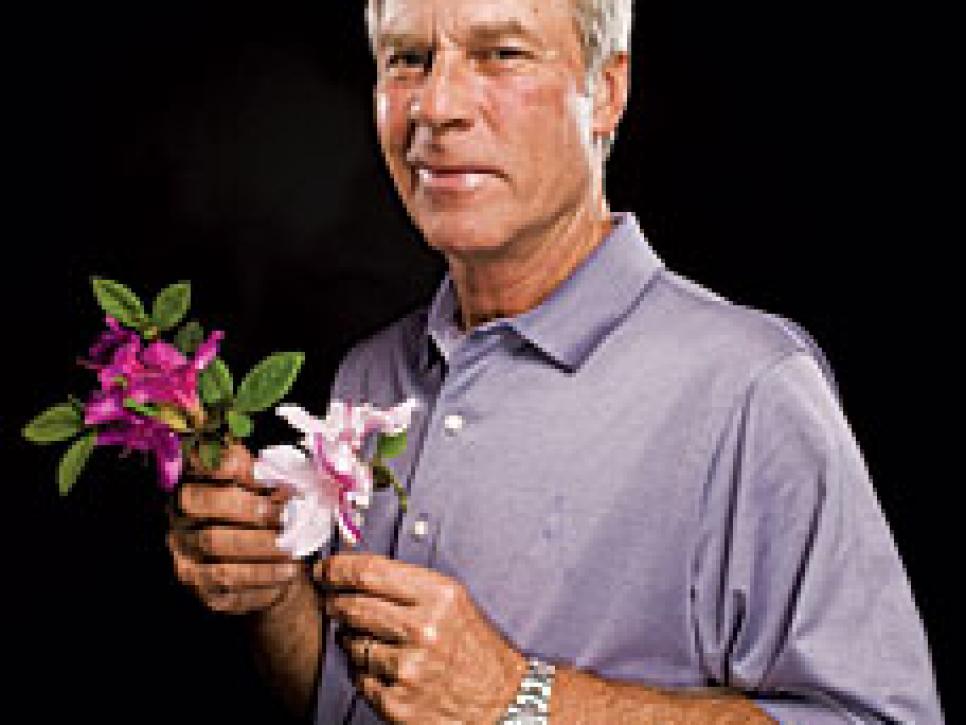

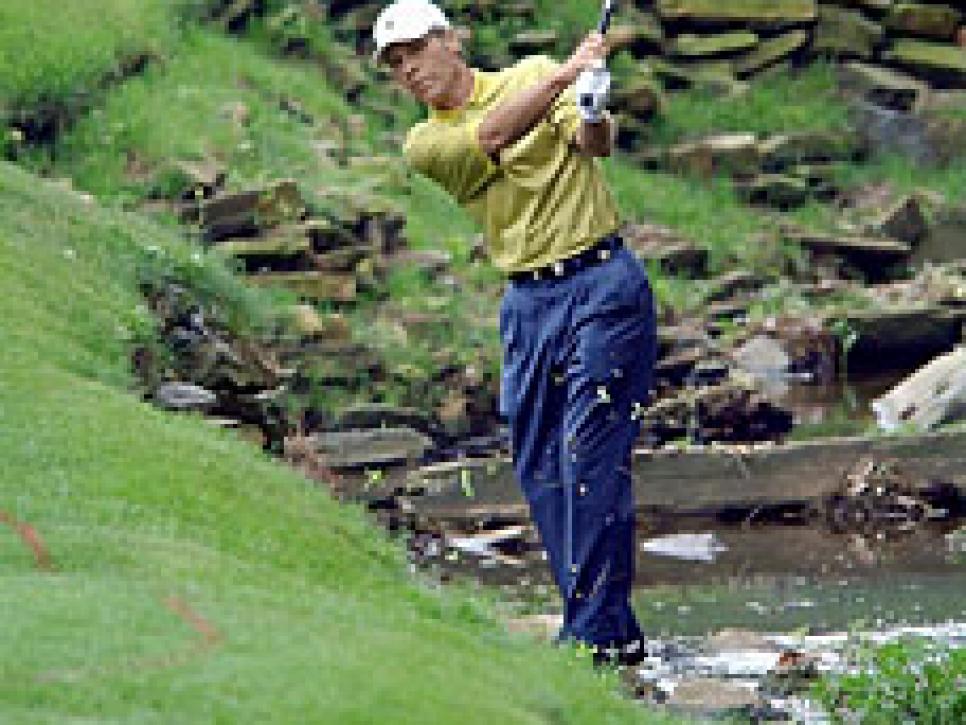

Sign of spring: Crenshaw's 37 trips to the Masters—he has nine top-10s to go with victories in 1984 and 1995—make him a perennial favorite at Augusta National.

Tally the weeks Ben Crenshaw has spent competing at the Masters and it adds up to more than nine months of his life. Each of those 37 springs, going back to his debut as a shaggy-haired 20-year-old amateur in 1972, has offered hope, and two of them delivered magic. "When you think of Augusta, you think of Arnold and Jack, but shortly after that, you think of Ben," says 1987 Masters champion Larry Mize. "He loves the place so much."

Twenty-five years since the first of his two Masters titles—a pair of the most popular victories in the tournament's history—Crenshaw will make his 38th journey down Magnolia Lane this month. Where groupies (Ben's Wrens) used to gather to watch him, grandmas now admire the father of three who still plays the game the way it ought to be played. He doesn't figure to factor in the outcome, because a 57-year-old golfer who drives the ball only 260 yards effectively is carrying a cap pistol against a bunch of guys shouldering bazookas. But for someone at Crenshaw's station in the game—and those who enjoy watching him play—the Masters isn't about winning, it's about savoring.

You won't be able to miss him. He'll be the compact man, built much like his golf hero, Masters co-founder Bobby Jones, making his way up Augusta National's immense hills. At times visible smoke will waft from a cupped left hand, the exhaust of a habit he hasn't been able to kick, and at others you will be able to sense the invisible steam after his trusty putter, older than most of the other players in the field, has done the unthinkable and let him down.

Crenshaw's history at the Masters is one both of statistics that can be counted and emotions that can't be measured. His 37 appearances are the 11th most in tournament annals, and he has made the cut 25 times, fourth behind Jack Nicklaus (37), Gary Player (30) and Raymond Floyd (27). In addition to his victories in 1984 and 1995, Crenshaw was runner-up in 1976 and 1983 and has finished in the top 10 seven other times.

Late on Wednesday afternoon before the 1995 Masters, the week his longtime mentor Harvey Penick died and the day of his funeral, Crenshaw flew back to Georgia from Texas, and stopped by the club to hit some balls under the watchful and informed eye of his longtime caddie, Carl Jackson. Then he went around to the practice green. "It was dusk but sort of hot, a lovely evening," remembers Crenshaw's wife, Julie. "It had been dreary and wet in Austin, where we had just buried Harvey, and now it was so beautiful. There is nothing better than to be in Augusta on a pretty spring day, looking at that beautiful golf course. Seeing him in that setting, it was like Ben belonged there."

Golfers average a shade less than 32 years old when they win their first Masters, so Crenshaw, at 32, wasn't really behind the curve when he arrived in 1984. But most golfers—even major champions—hadn't been what Crenshaw was when he was 21: a three-time NCAA champion at Texas, sure-fire heir to Nicklaus, a genial talent who respected golf's past while shaping its future. "He was the guy," says Larry Nelson, who went through Q school with Crenshaw in 1973. "Ben may have been the biggest thing to come out after Palmer and Nicklaus and before Tiger."

It wasn't as if Crenshaw was without success by the time he drove into Magnolia Lane in 1984—he won his first event after getting his tour card and had collected eight more PGA Tour victories by then—but he hadn't won a major championship or achieved anything close to Nicklausian dominance. "I couldn't believe some of the things that were written about me," Crenshaw says, reflecting on his early years as a pro. "But I never thought comparisons to people or what I was expected to do was a burden. I harbored dreams of winning big tournaments, but I had plenty of contemporaries—Lanny Wadkins and Johnny Miller, for example—who could really play the game. They were more consistent than I was."

On the 71st hole of both the 1975 U.S. Open and 1979 British Open, Crenshaw hit poor 2-irons that cost him a chance of winning. But he had also endured slumps in the manner of a pitcher who keeps getting sent back to the minors. The late Dave Marr, a close friend, liked to tease Crenshaw that he "was on his 21st comeback." Crenshaw's game had ebbed and flowed in the 1970s, but in 1982 he reached a nadir, as he plunged to 85th on the money list with only two top-10s. He even contemplated quitting. "We talked a lot about it," his father, Charlie, later told the Dallas Morning News. "I told Ben that the Good Lord gave him his swing, just like He gives it to an artist. I told him to whack away at it. Quit analyzing." The words, fittingly, mirrored what Jones' teacher, Stewart Maiden, once had telegraphed a frustrated Jones.

"There were a few periods in my career when I practiced a lot, hit plenty of golf balls," Crenshaw says. "The more balls I hit, the more complex things would become. My feel and instinct weren't good, because I was searching so much. I couldn't seem to put things together that way." He tried to believe Penick when he said his swing, right knee sway or not, was good enough, and he really took heart from something Marr told him about the myth of perfect ball-striking.

"I had seen Ben Hogan hit balls two or three times, and I didn't see him miss any shots," Crenshaw says. "I thought that was completely unattainable, that I couldn't come close to what he was doing. I remember asking Dave if he ever saw Mr. Hogan miss any shots. Dave looked at me kind of funny and said he saw Hogan hit some horrible shots. Hearing that helped me." Crenshaw also had purchased a MacGregor driver from a barrel of used clubs in Houston for $300. He gave up some length in the transaction, but he began finding more fairways than usual.

As the 1984 Masters rolled around, Crenshaw's mind also was clearing up with the realization that his nine-year marriage to Polly Speno, which seemed to have as many peaks and valleys as his game, was ending. A month earlier, he says they decided on their path. A week before, when he was playing in Greensboro, he found out she had formally filed for divorce. He closed with a 67 at the GGO to finish T-3. Jackson learned his boss' situation the next day. "Our first practice round, walking off the first tee, he broke the news to me," Jackson says. "He ended the conversation by saying, 'Carl, that's all right. We'll just win this damn thing this week.' "

"We had problems, and we couldn't work them out," Crenshaw says of his first marriage. "It was very difficult to get to that point, but I knew things were going to be OK."

Renting a small house near the club that he shared with his friends, country singers Rudy, Steve and Larry Gatlin, Crenshaw tried to concentrate on winning the major he wanted most. "There is something about that tournament and that setting that turns his juices on," says Charlie, Ben's older brother by 15 months.

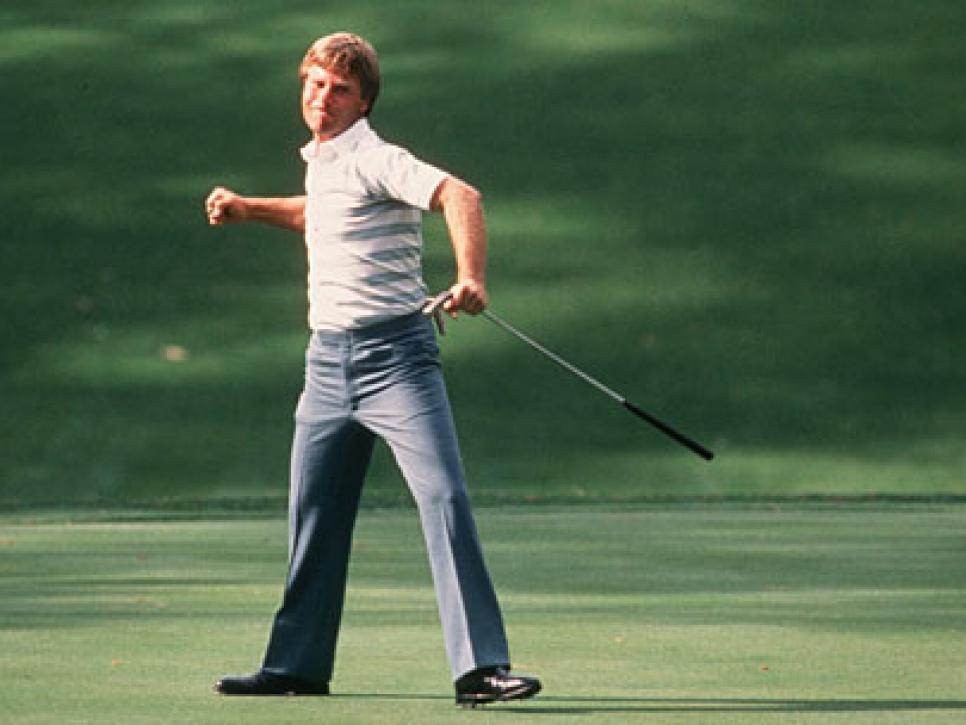

Crenshaw opened with a 67, matching his career low at Augusta. He stayed in contention into the weekend, and when he completed the storm-interrupted third round by playing five holes Sunday morning, he was tied at seven under with David Graham and Nick Faldo, two behind leader Tom Kite and one worse than surprise contender Mark Lye. A birdie by Crenshaw at the eighth hole tied him with Kite, whom he had been competing against for nearly 20 years. An eight-foot downhill birdie on nine gave Crenshaw the lead. On the long 10th, his 4-iron approach finished 60 feet short of the flagstick, leaving him a huge right-to-left slope to negotiate on a green that was marked by long, orderly shadows striping it like yard lines on a football field.

As the ripples were widening in the creek at the par-3 12th from a ball Nelson, then one stroke behind, had hit in the water en route to a double bogey, Crenshaw assumed his grip on "Little Ben," the Wilson 8802 blade putter his dad bought him for his 15th birthday.

"I was praying for a two-putt," says Jackson, who was tending the flag. "He started out putting west, and at the end the ball was breaking south. I would had to have walked six or seven steps to get to the line he started it on."

The ball, motoring pretty good, dived in the cup, and the roars rattled the trees. "Good night," Crenshaw said later that day. "I couldn't have made that putt again with a hundred golf balls."

It would be the signature stroke of a breakthrough week, appropriate for a golfer so renowned for his putting, although Crenshaw wasn't home free just yet. He holed a 12-foot birdie at No. 12 after a pure 6-iron to build a cushion. On the par-5 13th he was in position to go for the green with a fairway wood, but before playing his shot he thought he saw Billy Joe Patton near the gallery at the neck of the dogleg. Patton's chances of a historic Masters victory as an amateur in 1954 were drowned when his second shots at Nos. 13 and 15 went in the water. Crenshaw also waited to see what Kite, playing behind him in the final group, did at No. 12. When Kite, like Nelson, found the water, Crenshaw laid up. At the 14th, Crenshaw looked as if he was going to make a bogey but sank a slick 15-foot par putt that broke about 18 inches.

"I was disappointed in my own performance that day, but thoroughly impressed with how Crenshaw putted," recalls Faldo, who was paired with Crenshaw and shot a 76 to finish T-15. "I told myself to win this thing, you have to putt great. You have to find a way to manage yourself on the greens. You've got to have the touch and the temperament, and especially if you can hole the downhill putts, you're going to be tough to beat."

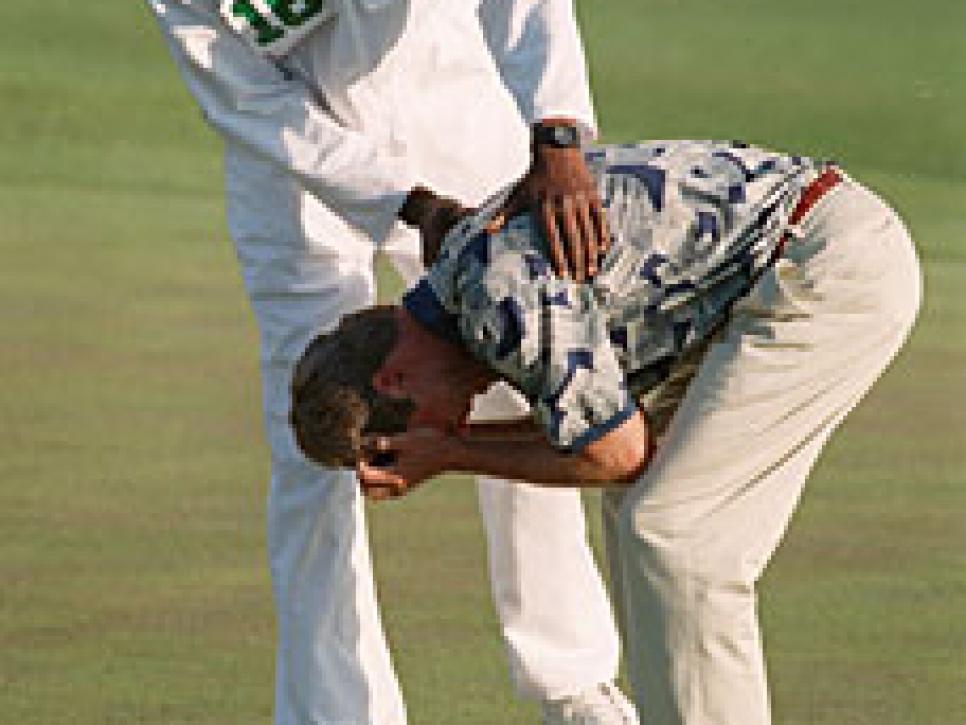

That Crenshaw picked up another major victory 11 years later, when he was 43, a week after losing his mentor, still baffles him. "I can't believe to this day I played that well on that particular week," he says. "As I've said many times, it's unexplainable. I played the whole week with [only] five bogeys, and I've never done that in a major, so there weren't many slip-ups. I had a very even-keel attitude that week, and I'm anything but that usually."

The themes of that week have been well-documented: Jackson giving him a tip to move the ball back slightly in his stance; Crenshaw using friend and business manager Scott Sayers' Cleveland facsimile of "Little Ben;" his game, largely dormant that season, coming to life. Says Charlie Crenshaw, "My sister-in-law, Julie, called me in Austin Saturday night and said, 'Your brother is going to win this tournament. You better get here.' " Charlie flew to Augusta Sunday in time to shoot some baskets with Ben in the driveway of his rental home. Before Crenshaw left for the course, Sayers noticed him grab a few minutes of solitude.

"About 30 minutes before we were fixing to leave, he walked down the driveway and stood by himself, thinking about things and what might happen," Sayers says. "I remember that clearly, his lone figure." Later, with Penick seemingly an unseen guiding hand, Crenshaw played even more solidly than he had in closing the deal in 1984, making birdies on Nos. 16 and 17 to beat Davis Love III by a shot.

Aside from the additional moisture from all the tears from folks who couldn't believe what they were seeing, Crenshaw's 1995 victory occurred on very much the same course where he had won in 1984. A few years later, however, in the wake of Tiger Woods' demolition of Augusta National in winning his first green jacket in 1997, the transformation of the Masters layout began: additional length in two waves (2002 and 2006), as well as the growing of a "second cut" of rough and the planting of many trees, on the first, seventh, 11th, 15th and 17th holes in particular. For devotees of the strategic style of architecture that Bobby Jones and Alister Mackenzie had in mind when they designed Augusta National, the changes were shocking. Crenshaw, who with partner Bill Coore has designed some of the game's most well-regarded courses over the last two decades (especially Sand Hills in rural Nebraska), was sympathetic to Augusta National's need to combat longer-hitting golfers, but not sold on the way the club went about it. After all, Crenshaw is someone who once told a reporter, "Many of the classical courses in this country were built between 1910 and 1930. They shouldn't be changed. They should be preserved like museum pieces."

For all the control club chairman Clifford Roberts and his successors exerted over the place—babies don't cry, weeds don't grow and blimps don't circle Augusta National the second week of April—the course rewarded a kind of abandon that has been diminished. Crenshaw's view? "He's probably too classy to say what he really thinks," a Champions Tour peer says.

While Crenshaw's critique is measured, he has opinions. Long pauses and hand gestures punctuate the conversation. Following the wholesale renovations in 2002, he says he wrote chairman Hootie Johnson a letter. "I tried to point out that the nature of playing the course had changed," says Crenshaw, adding that the two talked briefly when they saw each other at the Masters the next year. "We didn't speak long about it, but in his defense, he said they had to do something."

"It fell on deaf ears," Julie Crenshaw says of the letter. "Ben's opinionated, and he knows his architecture and what he's talking about. Ben totally agrees with a lot of the stuff they've had to do. But he also goes back to Bobby Jones and what they wanted to accomplish when they built the course. And the [new] trees and rough are not part of it."

The old Augusta was a tightrope, where risks were encouraged but a fall could hurt. "You always felt at Augusta you could take a chance on something, whether it was a tee ball or a second shot," Crenshaw says. "You had more room to play, and more people could play dangerously. It was totally different from any challenge in the world." To Crenshaw, the narrowing of the fairways from the equivalent of wide boulevards to country lanes altered things dramatically. "The second cut on lots of holes—that's first and foremost, because the course went from here to like this," he says, moving his hands very close together. "I think they needed to do something in the way of length, [but] I wouldn't have constricted it as much.

"There is no question it has become more of a defensive proposition," he continues. "The thing that set Augusta apart forever is that it's exciting and theatrical. People would pull off shots, but the flip side of that is that if you failed—and Jones wrote about this—it would tax you mentally. If you failed, it had a big effect on you. All I remember is how I felt there as a player [in my prime]. I hope the guys today are doing the same gyrations that we did. That, to me, is the question."

Crenshaw will need a fast course to help his chances. "If it's warm and dry," says Jackson, "we can make the cut and finish in the middle of the pack." It would be foolish to think there isn't a little magic left for Crenshaw, but not if he has to hit a 5-wood into the first hole, as has been the case in cool winds the last few years. "You make the cut, and you never know," says a hopeful Julie. "I guess it's fun, in a morbid sort of way," her husband says of the challenges of figuring out Augusta's roly-poly greens. Old-school to the core, Crenshaw calls them "keen."

For the fourth year, Crenshaw will preside as host of the Champions Dinner, a role Byron Nelson bequeathed before his death. Crenshaw sits at the head table with the reigning champion, everyone in the room clad in jackets the color of mint jelly you can't buy for any price. "I don't talk much," Crenshaw says of his duties. "I'm in awe of the people in that room. It's golf history right in front of me. We all know how lucky we are to be in that room. It means your life if you're a Masters champion. It's a prize that the more the years go on, you realize how fortunate you are. Not to take anything away from the other majors, but it's different."

Sayers has been to the Masters with his friend every year since 1985. "The place means everything to him," Sayers says. "It is a place in his life that signifies stability, that's a symbol of civility, consistency, the way people behave properly. Everything about golf that is good is exemplified to him by Augusta."

Some of the young bombers Crenshaw will be up against this year make pains not to even peek at a leader board, much less look for an apparition of Masters past. Crenshaw will try to concentrate on the things that keep the Masters timeless rather than the things that have changed so much. There will be moments when he sees the sun slanting just so through the pines, triggering so many memories and making him feel there is nowhere he would rather be.