News

It's Cool Being Tom

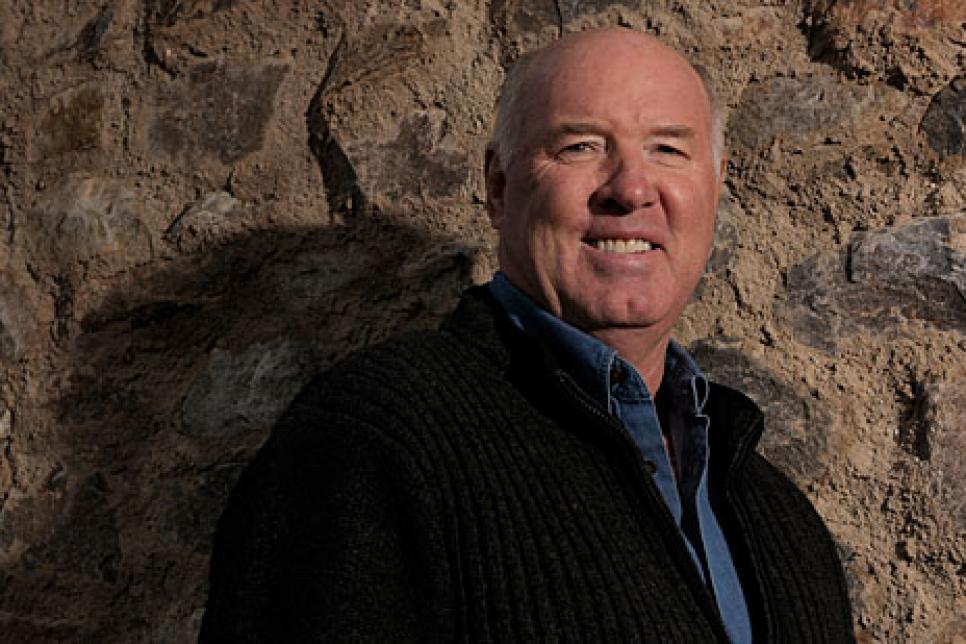

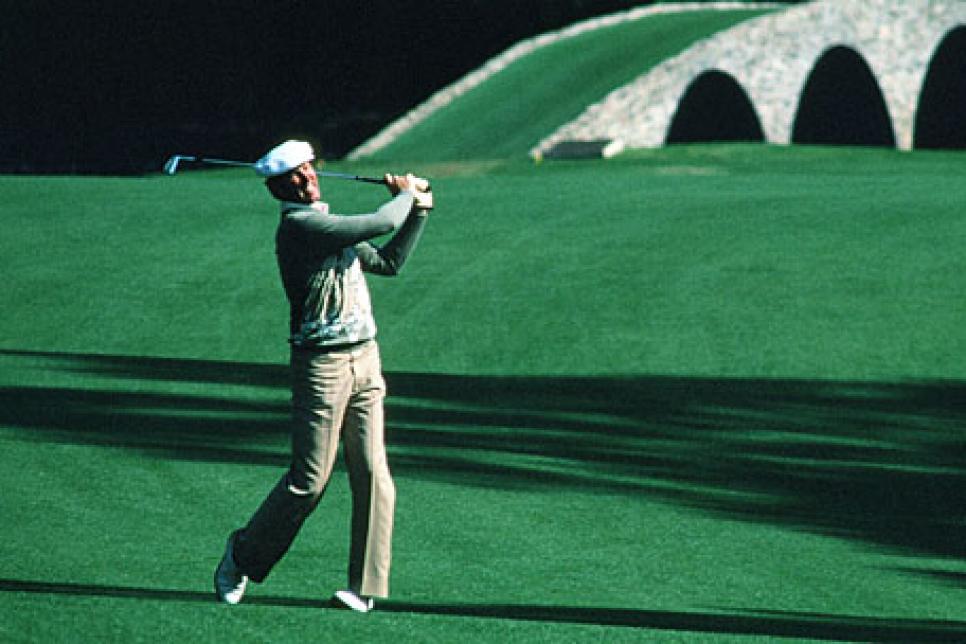

Shining moment: Weiskopf enjoyed the spoils of his lone major championship, the '73 British Open at Troon (Below), but today, at 66, he doesn't dwell on the past.

He still has the straight-backed military cadet posture that accentuates his significant height. However, between the chest and waist Tom Weiskopf's physical profile is skewed a little. There's a bit of a bulge up front. Well, why not? He's 66 years old now, doesn't drink anymore, or play competitive golf. With the long-held perception of his personality in mind—the most colorful expression of it being "The Towering Inferno"—Weiskopf is in something of a state of grace. He's very happy in his work as a golf architect, is contentedly remarried and, as one of the more articulate golf professionals of his or any other day, he has interesting things to say about his reputation as one of golf's most notable coulda-beens.

He had a classic golf swing. With superb balance, Hogan-like, he rotated his left forearm clockwise early in the backswing to put the club on a flatter plane than expected for someone 6-foot-3. His action gave him excellent ball control with great length off the tee. It was all there, which is why everyone expected so much from him. Everyone was shorted. Weiskopf as well?

"Oh yeah, I should have done more," he says. "But I don't dwell on it anymore. I will say this, though: If it wasn't for the fact that I love so much what I'm doing now [golf course design], I would probably be a very unhappy person."

Weiskopf won 16 PGA Tour events, plus five foreign titles, including his one major championship, the 1973 British Open. He shares with Ben Hogan and Jack Nicklaus the record for most runner-up finishes in the Masters—four. Weiskopf points out that for 17 straight years he was among the top 60 money winners and was the fourth player to win $2 million in a career. "Nicklaus, Trevino and Watson were the three before me—pretty good company." A consensus of those who were there in Weiskopf's day would say he shoulda won 50 tournaments, 10 majors and a zillion dollars.

What happened? There was, first and foremost, his temperament. He boiled at high-bubble when things did not go well. It's not that he threw clubs much or blurted the f-word a la Tiger Woods. He just steamed, the internal anguish rushing the color red up into his face like the mercury in a thermometer and overcooking his game. "He was his own worst enemy on the course," says Charles Coody, among many others.

What generated the heat? For one, odd as it seems to say, he was a gifted athlete. His father was a fine golfer with a beautiful swing; same with his mother. Weiskopf didn't take any formal lessons, and to this day when asked about his technique has little to say. The game came naturally to him, and when that happens, gifted athletes can have difficulty dealing with adversity and error. "I couldn't stand mediocrity," Weiskopf says. "I knew how good I was, what I was capable of doing, and couldn't accept a mistake. Another thing, I didn't start playing golf until I was 15, and within a year I was shooting in the 70s. Everyone was telling me how good I was, so with all of that you have these high expectations of yourself. And I didn't have a lot of patience."

Added to that was the Nicklaus vortex, into which every young golfer growing up in northern Ohio in the 1950s was caught. Weiskopf—three years younger than the man to whom he would so often be measured—perhaps a little more, given the stuff he was showing.

"To be honest, I didn't handle the Nicklaus situation well," Weiskopf says. "I got tired of hearing and reading about him all the time, and especially always being compared to him. I could hit the ball as far as he could, sometimes a little farther. I could hit my irons as well as he could. But I had a different makeup or personality, and I took the comparing thing very personally; that was a big part of it. I wasn't him, or even trying to be like him.

"The difference between Jack and me? Concentration, determination, but mainly motivation, which the great players have week after week, month after month, year after year. I had other things I enjoyed doing, that I looked forward to. Hunting, especially."

Sport psychology was just coming on the scene in the early 1970s, but many players then considered it effete to see a "shrink." In retrospect, Weiskopf wishes he had. "Absolutely. It would have helped," he says. "Thing is, I could go to a Masters or an Open and accept some bad shots. So I could train my mind for that particular week. I just couldn't do it on a weekly basis. I should have talked with someone."

And, Weiskopf acknowledges, he had a drinking problem. "I started drinking in college. My temperament on the golf course had something to do with that. I liked to party, to be with the guys, and I did nothing in moderation. That's my nature, the way I did things."

Even when at the top of his game he drank? "Oh yeah. Not quite as much, but I was young and could handle it," he says. "If I was playing well, I had a late tee time and had time to recover. All I needed was six hours sleep, a milkshake and a cheeseburger, and I was fine. I was in great physical shape then."

He quit cold turkey, but well after his tour days. No AA or anything. "I quit drinking and started skiing the same day," says Weiskopf. "In Montana. I got up the morning of Jan. 2, 2000, and asked myself why I put myself in this situation, feeling so bad a day after New Year's. I'm in this beautiful place, have the greatest life in the world, so why do I get angry sometimes, belligerent sometimes? I realized that most of the bad choices I'd made in life were related to drinking. So I quit, right on the spot. It was difficult, but about six months into it without a sip, I was at weddings or whatever and would do the toast with apple cider. A while later I was with friends at our favorite bar when I knew for sure I was never going to take another sip. It was near closing time, and I looked around at people and said to myself, Did I look and sound like that?"

There was another aspect of how Weiskopf approached the game that had a role in the outcome of his competitive career. I recalled with Weiskopf a conversation I had once with Gardner Dickinson, who had a fair career on the tour and thought a lot about the psychology of the game; he studied psychology in college. Dickinson made the point that great players never blame themselves for mistakes. If a drive is sprayed off line, a short putt is missed, it happened because of a sudden change of wind, someone snapping a camera, a tectonic plate shift. It is a ploy, a little white lie one tells oneself; whether consciously or not is beside the point. The idea is to not fault yourself. If you do, you diminish your self-esteem and confidence.

Weiskopf responded first with an anecdote. He was partnering with Jack Nicklaus in an alternate-shot match during the 1973 Ryder Cup. On one green Nicklaus asked Weiskopf to have a look at his putt. "I was surprised, because Jack did everything himself—did his own yardage, picked his own clubs, read his own putts," Weiskopf says. "But we were struggling, and I said, 'Put it on the left edge.' He hits the putt and the ball goes in the hole, just about disappears, but comes out. I told Jack I couldn't believe the ball didn't go in. He spun around, looked at me and said, 'I made it, it just didn't go in.' In other words, something else kept it from going in, it couldn't have been him.

"Now," he says, "let's go back to me. I blamed myself when something went wrong. I didn't make excuses. That was one of my problems. You can't play tournament golf that way. You have to let it go. Keep playing. I couldn't. I would dwell on [mistakes]."

In the end, the release from tournament-golf angst was Weiskopf's move into architecture. "At the end of 1984 I quit the regular tour, because of the way I was handling my temperament. I was offered an opportunity to work with Jay Morrish in creating Troon North in Scottsdale. I knew I had to get away from the game for at least a year, so I thought I'd see if I liked architecture. I could still go back on tour if I wanted to, but I never did."

He didn't go back to the PGA Tour, but after he turned 50, in November 1992, he joined the Senior PGA Tour. In the easier atmosphere of the Mulligan Circuit one imagined Weiskopf breaking some records and making a mint. He didn't do badly. From 1993 through 1996 he won five times, including the 1995 U.S. Senior Open at Congressional CC. "I had one goal in mind as a senior, to win the U.S. Senior Open, because it's the only championship for seniors that is pure. It's on a championship course at around 7,000 yards, has fast greens, rough, tough pins; you have to walk, it has a full field, and a cut. Jack beat me by a shot in my first try [ooohh!]; I finished tied for fourth the next year, and won it the third time out defeating Jack by four strokes [aaahh!]. I won twice in '96, then decided I didn't want to play anymore."

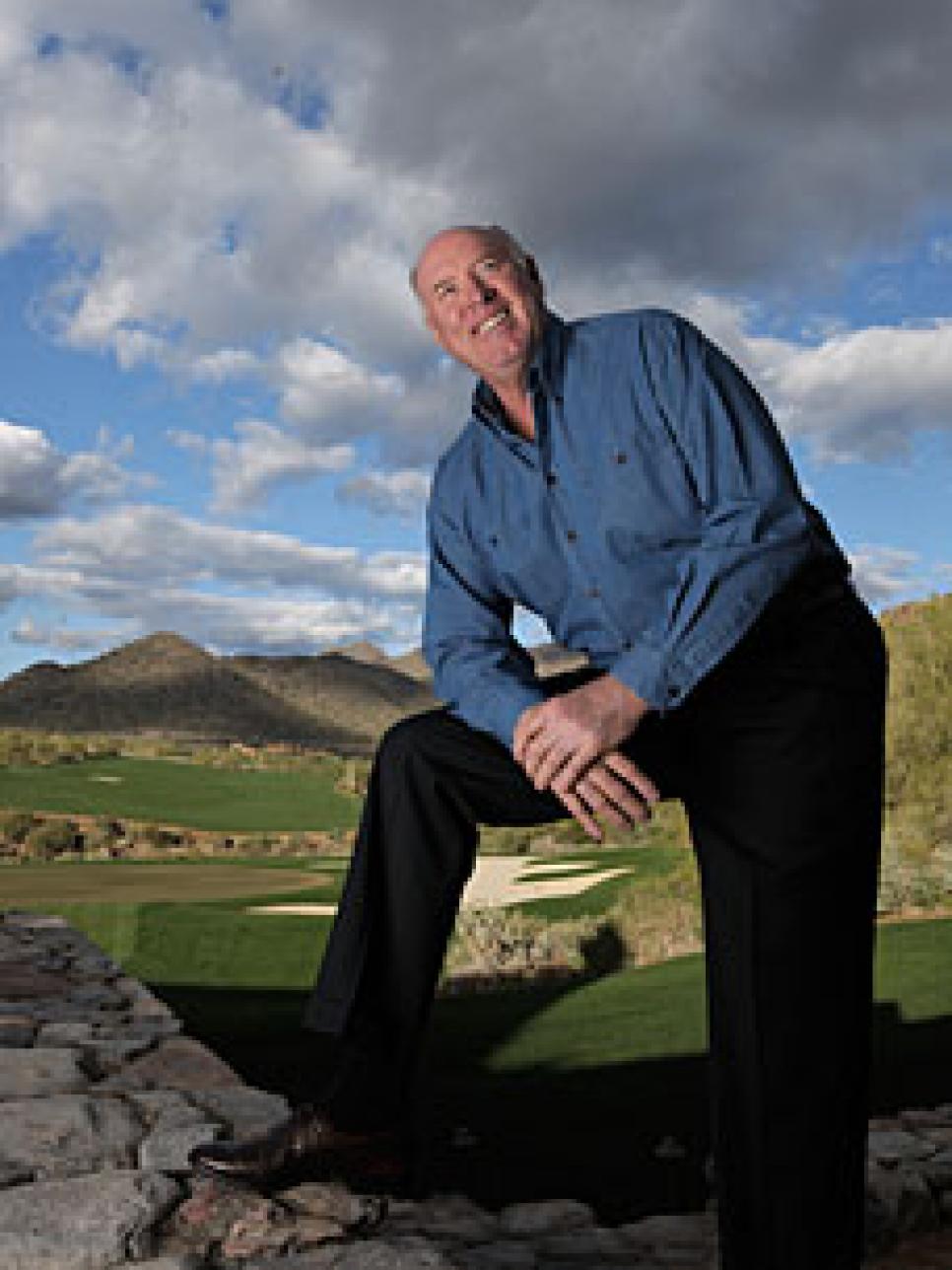

We talked on the veranda of his winter home in Scottsdale within the upscale Silver Leaf golf/home community. (He summers near Bozeman, Mont.) He designed the course, one of 53 on his résumé. Troon North was a big success, as were many others he did with Morrish, but Weiskopf always has been subject to doubt by the golfing public. When he and Morrish ended their partnership of more than a decade—an amicable break—many wondered if Weiskopf would be as successful on his own. His response is that he is not the sole creator of a course, but allows that Loch Lomond, in Scotland, may be closest to his personal vision. It was contractually a Morrish-Weiskopf project, but Morrish had had a quadruple bypass and participated only in the early routing. Weiskopf has said Loch Lomond is his "lasting memorial to golf," and indeed, it has gained considerable acclaim. Nick Faldo said it is "the finest golf course in Europe," and almost immediately it entered the top 50 in the world course rankings. (It is currently No. 11 among Golf Digest's 100 Best Courses Outside the U.S.)

His current partner is Phil Smith, who like Morrish has the technical expertise. Weiskopf's role, by his own description, is "conceptualist." Which is to say, his input is the essential strategic aspects and aesthetic characteristics of the holes put down. Loch Lomond is perhaps the ultimate expression of his design philosophy, which he denotes as classical. "There is no forced or unnatural movement of the earth, and no exaggerated or extra movement around every hole." He works with the topography, moves very little earth, and admits that "you're only as good as your piece of ground." Loch Lomond is set in verdant parkland at the foothills of the Scottish Highlands.

Weiskopf's 32-year marriage to Jeanne Weiskopf ended in divorce in 1999. He prefers not to discuss it, but it is interesting that it was less than a year later when Weiskopf had the epiphany in Montana severing the link to drinking that had tinged so much of his life. He and Jeanne had two children. Eric, 36, is a scratch golfer when he applies himself to the game. He has not yet found a career path. It's difficult to follow a famous father into the same profession. "No doubt," Weiskopf agrees. "The name brings instant comparison, which is so unfair." His daughter, Heidi, 38, is a successful interior designer. Weiskopf was a bachelor for seven years before marrying Laurie, who worked in real estate and appears to have a good handle on her husband's history and temperament.

For years an avid big-game hunter, Weiskopf has given that up for upland birds—pheasant, grouse, partridge. "I love my dog, and shooting a shotgun. I just have to be doing something different all the time."

My goal this year is to shoot my age. I came close last year--shot a 67.

—Tom Weiskopf

He has not given up golf, though; he just doesn't play competitively. "I still enjoy hitting good shots. I play well when I play. I sometimes go for a couple of months not playing, and then play six days in a row. My goal this year is to shoot my age. I came close last year—shot a 67. I play from 6,800 to 7,000 yards, partly because I don't hit it as far as I once did, but I just like that yardage.

"You know, awhile ago I got one of those chewing gum cards to autograph and the stat of my average drive was 275.3," he continues. "That was from my last three years on tour, which is when they started taking those statistics. I was in my prime then, and one of the longest hitters out there. Now, you're telling me that today's players are 40 or 50 yards longer than I was. B------t. It's today's ball more than the composite clubhead, the graphite shaft, the pushups and weight lifting. And something should be done about it. Slow it down, make it so it curves more, doesn't correct itself in flight, and have everybody on tour use the same ball."

Because Weiskopf runs a boutique shop—it's just him, Smith, and a secretary, Judy McCray—there is little overhead and he takes on at most three course-design and construction projects at a time. Thus, Weiskopf may not feel the current economic situation as badly as others. "Business in the U.S. has really slowed down," he says. "We are fortunate because we have international jobs." At the moment he has a 36-hole project being completed in China, ongoing jobs in Italy and Mexico, and a potential in Colombia. "I think there will be some opportunities, high-end stuff, but they will go to very few people," he says. "Maybe us."

As to his current state of mind, Weiskopf recalled comments Smith made to him not long ago. "Phil said how much he liked traveling with me, that in the 10 years we've been together I've never talked about my past unless someone asks. He said I love what I'm doing right now, and that's where I am. And he's right. You know, when I was playing I didn't take my game home with me at night, talk about it and so on. And I don't have any of my trophies in my houses. But damn it, I did take it out on myself on the golf course."