News

Crunch Time?

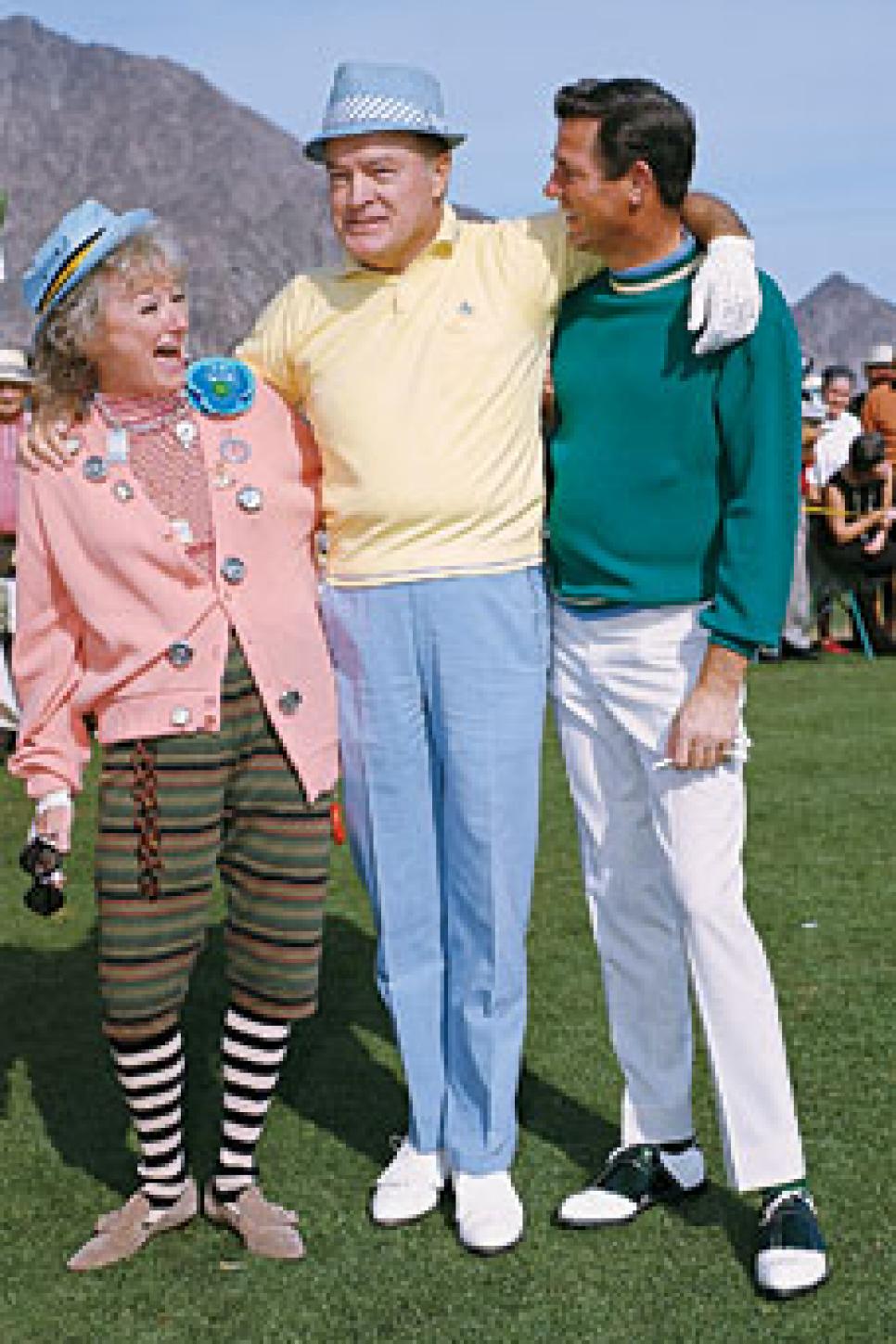

OLD FRIENDS: Palmer was the honorary host at an event he won five times and became good pals with the iconic entertainer.

Hope and change symbolized the mood for many Americans as President Barack Obama took office in Washington recently, but at the same time a similar theme was being championed three time zones away by Arnold Palmer, the incumbent King, one of few entrepreneurs in whom we can still trust. He was ubiquitous around the Coachella Valley, gladly celebrating the history and bullishly touting the future of a storied golf tournament that marked its golden anniversary Jan. 25 on a course designed by and named after this year's iconic honorary host.

Palmer won the first of these events in 1960, when it was the Palm Springs Golf Classic, and he won it four more times, including in 1973 when it was the Bob Hope Desert Classic, his last victory on the PGA Tour. That's a long time ago, but Palmer is a legend who connects with contemporary issues, as was evident in new signage. This was the "50th Bob Hope Classic, Hosted by Arnold Palmer," indicating the concatenation of circumstances contributing to a global recession. At the behest of a stressed and sensitive title sponsor, "Chrysler" was omitted whenever and wherever possible.

When local favorite Anthony Kim withdrew because of a shoulder injury, the Hope field contained one golfer in the top 20 of the World Ranking—No. 16 Steve Stricker. But the roster of celebrities seemed thin too, all the better to thank Bob Hope for the memories. PGA Tour commissioner Tim Finchem correctly identifies the spike of golf's popularity on TV with Palmer and the Masters on CBS. Still, that is not to dismiss Hope who, free of charge, served as a tremendous ambassador for the sport, whether twirling his club as a subliminal prop on USO Christmas trips overseas or hamming it up against snow-covered mountains every January on NBC, the network he helped make rich and famous.

"Our ratings were always terrific," recalled president and tournament chairman John Foster. "We had the weekend with no pro football, and our numbers were great. Just below the Masters every year, but often higher than the U.S. Open. If we weren't top two or three, we were top five." Last weekend, with the NFL taking a breather, NBC showed figure skating. The Hope was on Golf Channel, which also passed on mentioning Chrysler throughout comprehensive coverage that followed a tournament half a world away each day. (XM Radio's broadcasts were wheels off, too) "There is more competition than ever," said Davis Sezna, a first-year member on the Hope board of directors. "Years ago there wasn't Dubai or Qatar on the European Tour with a lot of the top pros, or Michael Jordan's annual bash in the Bahamas for his buddies in athletics and show business. That's the reality of what we're up against, but I have never seen a board as committed as this one to go forward while respecting the past traditions."

Deftly, Palmer addressed an inquiry about notable absentees. "I understand where you're coming from with the question," he said, "and how to answer it without getting into a crossfire is difficult. I would just hope players understand they need to support tournaments as much as they possibly can. I was a player, and I know you can't play every week. I used to try to spread my tournament appearances so that I never missed a tournament more than two years in a row. But when I hear some of the reasons for not playing, it disturbs me a little."

On that theme, Foster refers to Jan. 21, 2007, as a day that will live in Hope infamy. At the exposed Classic Club—a nice spot for windmills, according to 2009 champion Pat Perez (see page 46), but not golf—Charley Hoffman survived a brutal, cold gale to win. Earlier, after signing for 78, two-time Hope champion Phil Mickelson exited the scoring tent and spotted veteran Desert Sun writer Larry Bohannan. "Larry," said the left-hander, "are they going to use this course again next year?"

They did again, and Mickelson stayed home. "I kept talking to them about that place, the Classic Club, and they wouldn't back off their stance," Mickelson said recently. "Now, though, they're starting to do things to get more guys to go back there." Foster, upon reflection, characterizes 1/21/07 conditions as borderline unplayable. Whatever, following last year's tournament, the Hope committee abandoned the Classic Club, which had been donated by the H.N. Frances Berger Foundation at no cost. In its place was the Jack Nicklaus Private Course, adjacent to the Palmer Private, at PGA West. The Nicklaus Private was the third new course in the last four years to make its Hope debut. The Classic Club came aboard in 2006 and lasted two years. SilverRock was first used last year.

Under still weather until wind arrived for the final round, on pristine fairways and greens, par was a rumor last week, but as 2000 Hope champion Jesper Parnevik mentioned, "That's good … because this tournament is better when it isn't like all the rest of them." Even Finchem concurred that the Hope had "tilted" toward more challenging layouts and now is reverting to its roots. And why not? It's early in the season, there are five rounds and four different courses with 72 holes among amateurs. "Let the guys get warm, make some birdies and build some confidence," said the commish. "We don't have a problem with that." Indeed, the Hope always has been about fun, and what's more fun than shooting 63? Also, if courses are more "beatable"—to use Finchem's word—amateurs will enjoy their experience more.

Suggestions about reducing the Hope to four rounds instead of five don't gain much traction: 72 holes before a cut in virtually guaranteed good weather is a bonus, said Finchem. Perhaps stability would be an option. That is, stick to the same four courses every year. "I think that's part of the reason maybe some guys don't come back," said D.J. Trahan, last year's victor. "I think it would be a tremendous draw if they could set a good rotation of four courses and keep it going. It's just really hard when you have guys who need to play four different courses and they have only a couple days to prepare, especially guys coming over from [two season-starting events in] Hawaii."

Palmer's being chosen the 50th anniversary host is a one-time only request, according to Foster, not that the King, who turns 80 this September, would be unwelcome to preside over the 51st. Whether the tournament needs a celebrity host is another matter, currently under discussion by Foster and staff. Whoever assumes the role will have to defer to the legacy of Bob Hope, who passed away in 2003. Palmer is comfortable in that role, of course. Besides Hope, the King has made lifelong friends with committee members such as Ernie Dunlevie, chairman emeritus. He was a pall bearer at Clark Gable's funeral—talk about history. Shortly after Hope's death, comedian George Lopez became the host. By all accounts, he dived into the task with vigor. But he discovered last spring that he would not be asked back. "I guess they didn't like my swagger," Lopez told the Los Angeles Times.

Foster said he has heard that the committee deemed Lopez too "edgy" but does not profess to agree. "I don't know where that came from," said Foster. "George did everything we asked. He did a terrific job. We just decided to go in a different direction." A number of pros cited a lack of buzz last week, and Mike Weir, for one, invoked Lopez' name. "I thought he brought a lot of energy to this tournament," said Weir. "Obviously, Arnold Palmer is great, but I was disappointed the way the Lopez thing was handled. George busted his butt the last couple years, and I don't think they treated him right." Weir, the 2003 Hope champion, said Lopez asked him to join the celebrity rotation. Last week, not explicitly out of protest, Weir rejoined the starless fields featuring amateurs who paid no less—and in some cases, significantly more—than $12,000 per for the privilege. "By the way," said Foster, "as tough as things are everywhere, we sold out all those spots, and we had a waiting list. A long waiting list."

The aforementioned strife within the automobile industry is obviously an issue at the Hope, and by no means a side issue. Chrysler's attachment to the PGA Tour decreased even before the current crisis, but the company had a long relationship with Bob Hope and his tournament. Chrysler sponsored the event on TV starting in 1964, then became title sponsor in 1986. But with a bailout or rescue plan for the Big Three automakers pending and a new President in place, uncertainty prevails. There was a whiff of optimism last week when Fiat of Italy was said to be a willing international partner, but for the first time in memory, there were no Chrysler executives in or around the Hope—only 20 dealers who received pro-am spots for jobs well done. "Chrysler has a contract with us until 2010, and they've said they will honor it," said Foster, who allows for the possibility that by next January, Chrysler might cease to exist. "We would be able to continue putting on a tournament for a couple years without a sponsor if it came to that. We've been through rough times before. Remember, Chrysler was on the brink of bankruptcy 30 or so years ago until Lee Iacocca took them over. During that period, Chrysler stayed with us."

Finchem expects the tour will lose sponsors in the next couple years. "I don't think there's any question about that," he said. "I do know that Chrysler, like a lot of companies on the PGA Tour, is there for a reason. They get value, and they believe they get a lot out of it, and in Chrysler's case, I believe that if they can possibly see their way through to continue, they will continue. But we'll just have to wait and see. They are no different than a lot of other companies we have relationships with. It's just that they have been a very long-time partner. If something happened here with Chrysler, our first effort would be to find a new sponsor, and we do have some candidates out there, despite what is occurring in our economy."

Elsewhere, the hymn is similar. Larry Peck, promotions manager for Buick/Pontiac, said corporate presence during the upcoming Buick Invitational at Torrey Pines will be minimal: 20 dealers will be on the premises, but at their own expense. Meanwhile, hospitality tents will not be nearly as lavish. "Dry snacks," Peck said. "Still, golf is in our DNA and has been for years. We've cut back. We're not with Tiger Woods anymore. But we still need to advertise and promote our products. One could argue that we have to do so more than ever." CNBC financial whiz Joe Kernan, a combatant in last week's Hope, seconds Peck's notion—during a downturn, spreading the word is vital. Warning flags are not reserved for Detroit's ailing Big Three. BMW signed on to sponsor one of the four FedEx Cup playoff events through 2012, but the company has an out after next year's tournament at Cog Hill GCC near Chicago. Should the U.S. unit sales decrease 10 percent during a 12-month period leading into the 2009 event, BMW would have the right to terminate its agreement two years early.

Before armchair critics dismiss the Hope as a hopeless cause that should vanish out of convenience, consider that the tournament is closing in on the $50 million mark in charitable donations. There are buildings, hospitals, emergency-care centers in the area that wouldn't be standing if it weren't for this tournament. There were unconfirmed reports about potential Hope sponsors—incognito, no telltale corporate logos—touring the grounds during the tournament, just in case. (It is no secret Justin Timberlake is interested in better dates; then there's this outside-the-box concept: somehow combining the Hope with Jordan's annual bash.) Concluded Finchem: "I feel more concerned about the economy than I did four months ago." Indeed, on Inauguration Day, after Obama and Palmer spoke about a brighter tomorrow, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted 332 points.