News

Mr. Incredible

The right stuff... again: Woods' magic was clear on a 40-foot eagle putt to conclude the third round.

Many things have been said about the 2008 U.S. Open, won by Tiger Woods in a playoff with Rocco Mediate, almost all of them superlatives. Here's another: It was probably the greatest performance by one man in a major championship, ever.

Pay attention to those qualifiers, because we are not saying Torrey Pines was the best major ever. It lacked two vital components: a larger and more renowned group at the top of the leader board throughout the tournament, and a shootout between at least two of the game's top names down the stretch. Several events with those qualifications would include the Masters of 1942, 1954 and 1986; the U.S. Opens of 1913, 1960, 1967, 1971 and 1982; and the British Opens of 1977 and 1984, with the greatest of them all probably Jack Nicklaus' epic victory at Augusta in 1986.

Our declaration also is different than the finest individual demonstration of pure golf in a major. Plenty surpass it, including Woods himself at Augusta in 1997 and Pebble Beach and St. Andrews in 2000. Other examples would include Ben Hogan at Oakland Hills in 1951 and Augusta in 1953; Jack Nicklaus at the 1965 Masters, the 1967 and 1972 U.S. Opens (at Baltusrol and Pebble Beach); Arnold Palmer in the 1962 British Open at Troon; and Nick Faldo at St. Andrews in 1990. That's just a short list.

Torrey would even fall short as the most compelling display of courage and character by a major winner. The two stalwarts in this division are Hogan's playoff victory at the 1950 U.S. Open at Merion only 16 months after suffering near-fatal injuries in a car crash, and Babe Didrikson Zaharias, already ravaged by the cancer that would take her life less than two years later, winning the 1954 U.S. Women's Open by 12 strokes. A third is Harry Vardon taking his sixth British Open in 1914 at 44 after recovering from tuberculosis, a performance that too often is overlooked.

But in terms of a boffo one-man show, Woods at Torrey beats them all. Yes, Francis Ouimet's Cinderella story at Brookline is authentic Americana, while Hogan's ascetic odyssey at Carnoustie in 1953 crowned his legend. Woods, however, had two built-in advantages over those sagas: He was the most compelling figure in all of sport, and his stage—along with being on the edge of the Pacific—was an electronic one that played before millions in prime time on the East Coast. He came with a fully loaded backstory and then provided compelling daily installments complete with increasing tension, a stoic but clearly fierce battle against seemingly overwhelming obstacles. Sunday ended with an incredible climax, and Monday's playoff was a killer encore. As golf theater—a term that to the casual sports fan is oxymoronic—it was transcendent.

The week provided plenty of meat for Woods' role.

1) He was hurt in a way that affected his performance.

Golf injuries are funny things. Woods had ruptured the ACL in his left leg 10 months before, but still won 10 of the 13 events he had played. So while the same injury would send an athlete from any other major sport to the sidelines, it really only hindered Woods in his ability to make the swing he would have preferred to make. He still was able to play winning golf.

But what made Torrey a torture chamber were the two stress fractures in his tibia that Woods suffered two weeks before the tournament. They had occurred as he was trying to prepare for Torrey after undergoing surgery in mid-April to repair cartilage damaged by playing on the bad ACL. The stress fractures limited his pre-tournament preparation to just a few practice balls a day and only nine practice-round holes at Torrey Pines.

Once the tournament started, the pain kept getting worse. The only visible indication during his opening-round 72 was a grimace after unleashing a 350-yard drive on the par-5 18th. By Friday a slight limp was discernible, and Saturday and Sunday saw him bend over and stop several times after shots while the pain subsided. Each evening after his round, trainer and physical therapist Keith Kleven would work on Woods from after dinner until midnight, trying to reduce the swelling and block the pain, then have another session in the morning. The pain was a problem, but what really made it difficult for Woods to play was the increasing weakness in the area of his knee. Because the knee was buckling, especially with the longer clubs, Woods was hitting a lot of pull hooks, a shot he almost never hits, even when he is playing poorly.

2) He played some really bad golf.

It is often said the winner of a major is not the player who hits the most good shots, but the player who makes the fewest mistakes. Mostly because of his physical condition, Woods made an inordinate number of uncharacteristic mistakes.

He opened the tournament with a pulled drive on the first that led to a double bogey. All told, bad drives would lead him to double-bogey that hole three times. He made another double bogey in the first round after a pulled drive on the par-4 14th.

Most startlingly, Woods made some huge errors at what would otherwise be winning time. The worst occurred with his 3-wood second shot to the par-5 13th Sunday, where he held a one-stroke lead. He had hit a perfect drive. Seeking a championship-clinching birdie with 270 yards to the front of the green, Woods knew the only place he could not miss was way left into iceplant that had been designated a lateral hazard. But that was exactly where he hit it, and the resulting bogey cost him the lead. A pushed drive into deep rough on the 15th led to another bogey and put him a shot behind. Needing a birdie on the 72nd hole to tie, Woods drove into the left fairway bunker and then, with a 9-iron, hit a fat push into the right rough. The shot was so bad at such an inopportune time that Woods, after throwing his club down into the sand in exasperation, picked it up and whacked his golf bag so hard three balls fell out.

3) The really bad golf required that he play some truly spectacular golf.

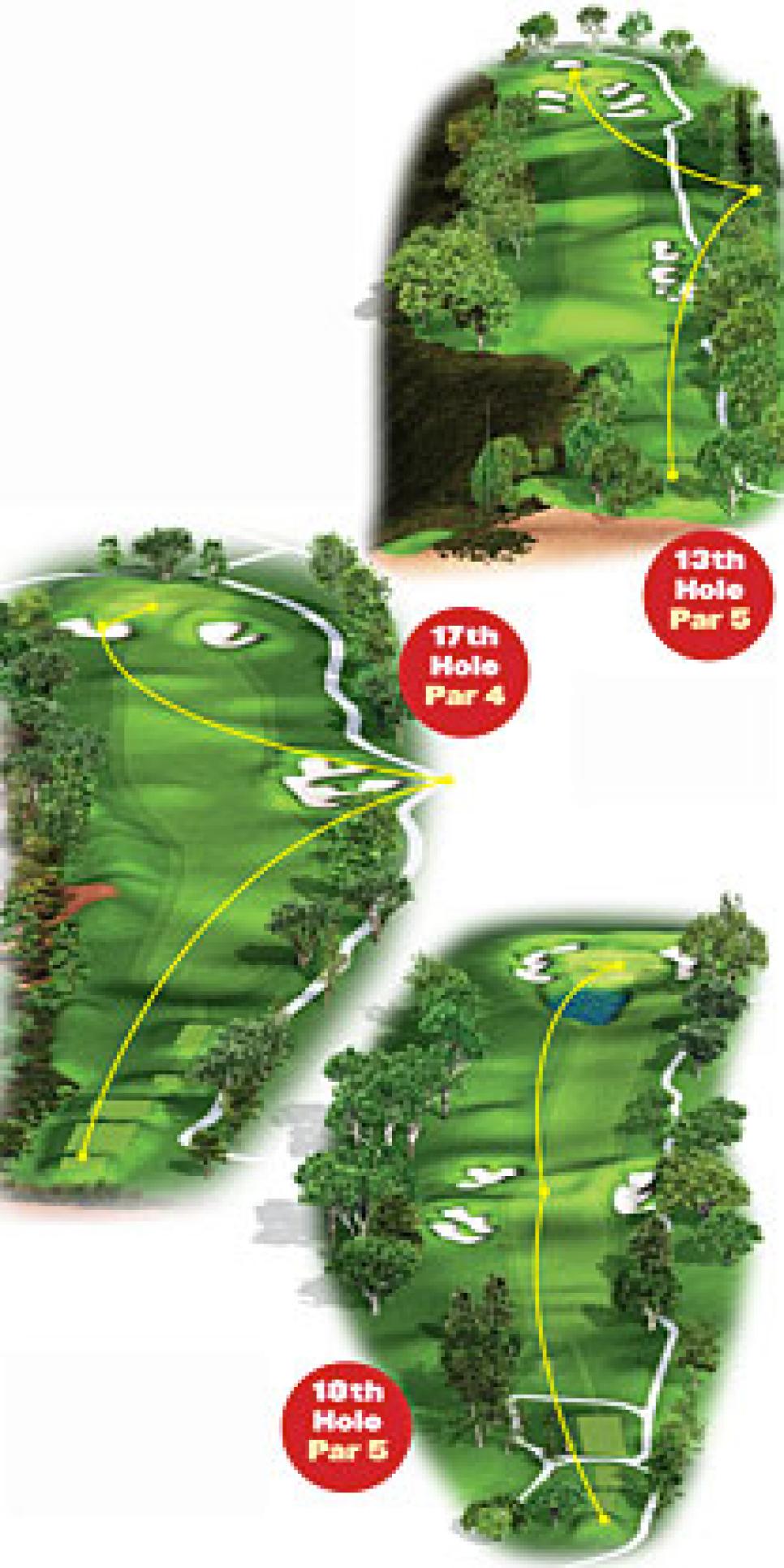

It would be hard to come up with a tournament in which Woods has added more shots to his career highlight reel. Friday, he got back into the thick of things with a 68 punctuated by an eagle on the 13th after a 266-yard 5-wood shot to 10 feet. Saturday's third round provided the most material, where he made eagle on the 13th by holing a downhill 66-footer with some 20 feet of break, and on the 18th, where a curling 40-footer dropped to a deafening roar. The eagles framed a lucky chip from deep greenside rough on the par-4 17th that took one hard hop before banging into the flagstick and dropping for birdie.

__4) He was incredibly clutch. __

Woods' greatest quality was never more in evidence than at Torrey. Every time he absolutely had to have something, he got it. Though he had every reason to lack confidence in his ability to control the golf ball, he came up big just when it looked as though the hill was getting too steep. Sunday and Monday, he made several par-saving putts in the four- to 10-foot range to keep himself in the game. His 101-yard third to the 72nd hole joins the exclusive pantheon of gritty approaches to the final hole of a major.

Essentially, Woods had to invent a shot. Because the distance would require that he take something off a 56-degree wedge, the shot would carry insufficient spin to hold the right front of the very firm surface where the pin was located—meaning that the only shot with a 56-degree that could get close was a bounce-up. Woods, with urging from caddie Steve Williams, rejected this option because the steep slope in front of the green made judging the bounce too chancy. They instead went with a full-out 60-degree wedge shot, a club Woods normally doesn't hit more than 85 yards. The extra clubhead speed, combined with the clean contact Woods' skill allowed him to achieve, carried the ball to just short of pin high, and the subsequent big bounce was negated by heavy backspin that brought the ball back to within 12 feet.

Overlooked was Woods' drive on the 18th hole of the playoff. Still trailing Mediate by one, and having sprayed several tee shots in the last two days, he piped a high cut into the middle of the fairway to set up a 4-iron into the heart of the green.

"Tiger is not the best putter statistically, yet there isn't anybody who wouldn't tell you Tiger's not the best putter because he is so clutch," says Hank Haney, his coach. "He's not the best driver, accuracy-wise, but his ability to hit good drives under pressure is probably underappreciated. How many bad drives has he ever hit that have really cost him? You can't remember them."

Also overlooked—because he makes such putts with unprecedented regularity—was the do-or-die four-footer for birdie Woods had to make to catch Mediate and keep the playoff going after his eagle putt from 45 feet ran past. Woods' subdued yet clearly relieved reaction after holing the downhill slider showed that the effort had taken all the nerve he could muster.

__5) He hit the greatest 72nd-hole putt in a major ever. __

Until Torrey, Bobby Jones' curling 12-footer for par on the 72nd hole at Winged Foot to get into a playoff with Al Espinosa at the 1929 U.S. Open was the gold standard in this category. But because of all the drama that had preceded it, because of the huge throng present (as well as the worldwide audience watching on television), because Woods' perfect record in closing out majors with a 54-hole lead was at stake and because this seemed the ultimate test of his uncanny ability to simply get it done, Woods' feat in holing his 12-footer was superior to Jones'. His thought as he stood over it? Surprisingly fatalistic. "Just make a pure stroke and hit a pure putt," he said recently while recounting the moment. "That's all you can control. After that it's up to the golf gods."

__6) And imprinted it with the greatest celebration ever. __

Going back to his reaction to holing the birdie putt from off the 17th green at Sawgrass to finally take the lead in the final of the 1994 U.S. Amateur, Woods' celebrations have exhibited passion that could at first be off-putting in their intensity, but with time and reflection validate his exceptional ability to be in the moment.

When the putt dropped at Torrey, Woods seemed to be focused heavenward more than in his other exultations, and his wide stance and backward lean evoked a bit of Rocky Thompson. But never has a shot produced a more complete, unrestrained and satisfying release of tension and gratification.

__7) He beat a very worthy antagonist. __

Sure, Rocco Mediate wasn't Snead or Palmer or Nicklaus. But he was a man in an Open Coma with a nothing-to-lose attitude. His jocular and chatty manner, not unlike that of the kind Lee Trevino took into his playoff against Nicklaus at Merion in 1971, could also be potentially wearing on an opponent. He was a very dangerous man.

Woods made sure he let Mediate get a headstart on him down the fairway on most holes, to avoid long conversations that could have taken him out of his preferred zone. In the end, Woods was never disarmed while Mediate remained a likable antagonist who enhanced the drama.

__8) Woods called it his "greatest win." __

And he's not given to superlatives about his golf. Enough said.

Saturday Splendor

Tiger Woods' incredible six-hole stretch to end Saturday's third round at the U.S Open at Torrey Pines began and ended with long eagle putts at Nos. 13 and 18. The run also included a "lucky" chip on 17 that bounced once on the green, hit the flagstick and fell into the cup, producing an embarassed hidden-behind-his-hat smile from Woods before a celebratory high-five from caddie Steve Williams. During the stretch he went from four strokes back of Rocco Mediate to one stroke in the lead.

Word For Word

__"He's just so hard to beat. He is who he is. There's nothing else to say." __

Rocco Mediate, after taking Tiger Woods 91 holes before losing the U.S. Open at Torrey Pines.

__ "I'm glad I'm done. I'm done. I really don't feel like playing any more. It's a bit sore." __

Tiger Woods, after winning the U.S. Open on a knee that was surgically repaired in April. Two days after the victory, Woods announced the knee would require additional surgery and that he also was playing with a broken left tibia.

__ "I'm not sure the range is the place to go really. A padded cell might be nice." __

Paul Casey, when asked if he planned to practice after shooting a third-round 76 at Torrey Pines.

__ "It's pretty good. I think for me, I can't speak for Bart—of course, I usually do. But that comes from my upbringing." __

Brad Bryant, on what it was like playing with his younger brother, Bart, in the U.S. Open.

__ "I still think it was the correct decision, but Phil had to make it. I don't know anybody who can hit a driver straighter than a 3-wood."__

Short-game swing instructor Dave Pelz on Phil Mickelson's decision to remove the driver from his bag during the first two days of the U.S. Open. It was a strategy that backfired when Mickelson hit just 12 fairways in two rounds—shooting 71-75. He reinserted the driver to his bag for Saturday's third round.