News

Hogan's Heroes

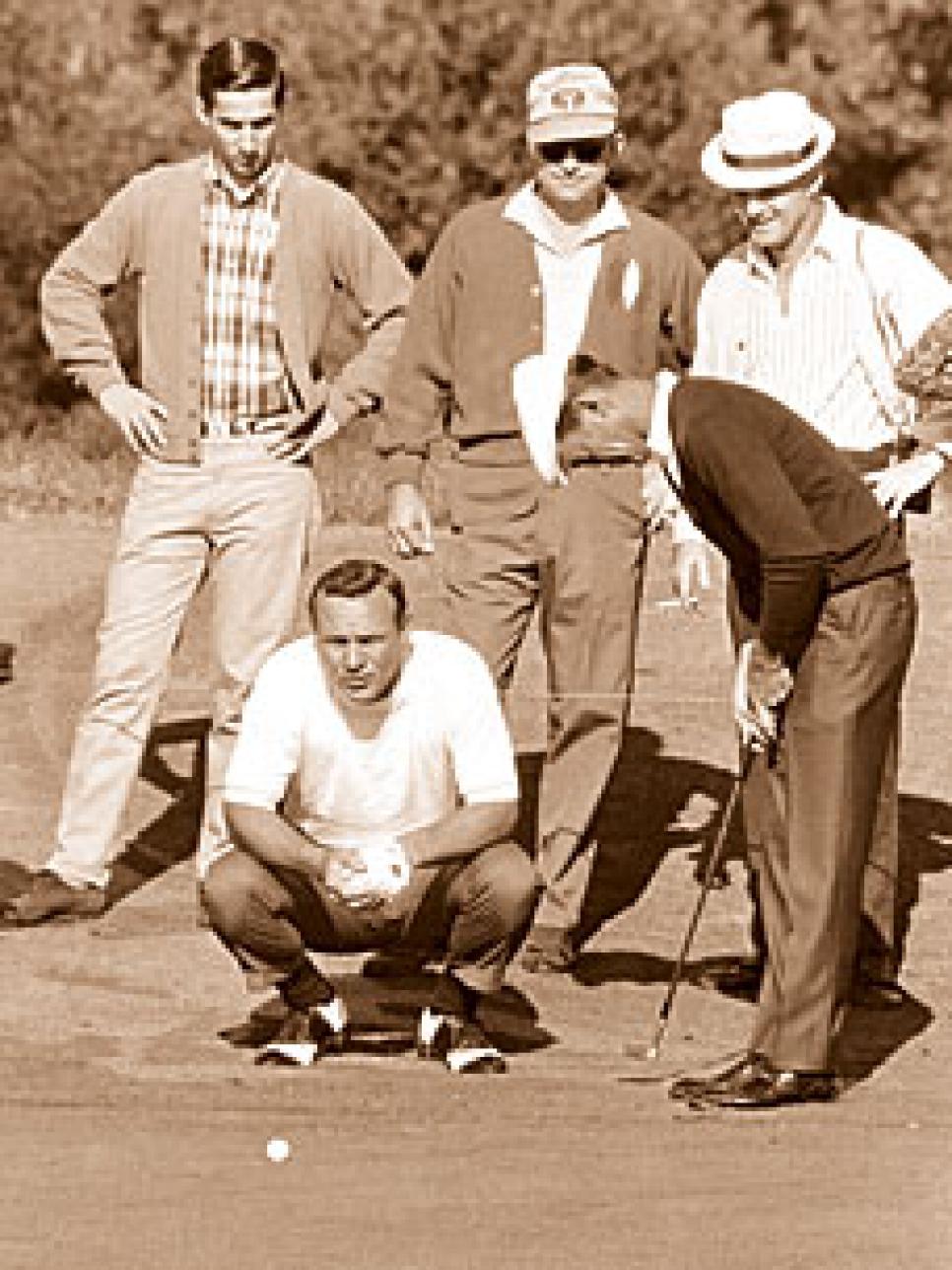

American superiority: Ben Hogan introduced his team as the "finest golfers in the world." (Left to right) Al Geiberger, Julius Boros, Arnold Palmer, Gardner Dickinson, Hogan, Gene Littler, Billy Casper, Johnny Pott, Bobby Nichols, Gay Brewer and Doug Sanders after their 15-point victory over Great Britain.

Funny, the tricks and treats memory plays after 40 years. The 1967 Ryder Cup Match at Champions GC in Houston made plenty of history, but it's a series of behind-the-scenes happenings that comes to mind first for a well-seasoned journalist who covered it early in his career.

Historically, it was the most lopsided victory ever, the Americans winning by 15 points (23½-8½) and nearly killing the event—and doing it without Jack Nicklaus, who wasn't eligible because he hadn't been a PGA member long enough. The beating led the Brits to switch to the larger American ball and change their fortunes for the better, much the better. It was the only time the cup was contested in Texas. It marked America's first good look at England's Tony Jacklin, who would go on to win major championships on his own ball and revive British cup fortunes as their enterprising captain.

And it added tellingly and entertainingly to the lore of Ben Hogan, the enigmatic U.S. captain … and continues to add to it through latter-day visits with living protagonists in the drama. These venerable, colorful personalities are not necessarily more talkative now that Hogan is gone (they've always been better company than their modern successors), but it doesn't hurt. Hogan was an intimidating force to the end.

For all of the '67 match's record-book material, the sharpest images I still revisit are mostly not a matter of record (I had to refresh myself on a few facts). They are more impressionistic, more personal, more unexpected at the time.

I will never forget watching Hogan, the famously austere Hogan, climb on a folding chair so he could see over the crowd as the University of Houston marching band emerged from an early-morning fog shrouding the first hole to launch the opening ceremony.

I will never forget the four surviving members of the first U.S. Ryder Cup team in 1927—Johnny Farrell, Joe Turnesa, Wild Bill Mehlhorn and Al Watrous—showing up for a ceremonial nine holes. All are gone now.

I will never forget being repeatedly refused admittance to the players' locker rooms in my callow youth, never mind proper credentialing. Two veteran golf writers, Waxo Green from Nashville and Charlie Bartlett from Chicago, had adopted the Ryder Cup rookie for the week and found his futile arguments with the rent-a-cop guarding the door unnecessarily humorous.

Charlie, who died suddenly later in '67, was a legend in journalistic circles. He was the first and long-serving secretary of the Golf Writers Association of America (he claimed he was elected after he had left the room to take a call from nature). An annual GWAA award named for him goes "to a playing professional for unselfish contributions to the betterment of society."

Charlie contributed heavily to the betterment of our fraternity if not society at large. A statistics hound, he took a cue from baseball, another of his favorite sports, to pioneer meaningful golf stats taken for granted today—and taken to an extreme. He tracked greens in regulation, fairways hit and putts, among other categories he developed. He chased down all the information himself and carried a little box containing his database.

I will never forget that the thoughtful Charlie and Waxo, who could have been wealthy had he written as amusingly as he told stories, took me one evening during the week to a football game between Rice and SMU, two big-time programs at the time. I vaguely recall that Rice won, but remember that the game was played at night because of the Texas heat (the Ryder Cup having been moved from September to October on the same account).

I will never forget Arnold Palmer buzzing the course one afternoon in his private plane, a Jet Commander, so low to the treetops—if not below them—that he was reported to the FAA and feared losing his pilot's license. Peter Alliss, a British Ryder Cup mainstay for 16 years and son of a Cup star, says now, "We couldn't believe a golfer had his own plane."

Hogan couldn't believe Palmer had pulled the stunt. Doug Sanders, a teammate talking today, says the captain benched his star in the following round over the incident. Hogan would not have been pleased either that Palmer took Jacklin and some of his British teammates up with him for the joy ride.

Asked by an intrepid reporter (not this one) why Palmer was not playing in the morning four-ball the next day, Hogan replied, "Because I am captain and I say so."

The reporter asked if he had any reason.

"Yes," Hogan said.

Could the reporter ask what it was?

"You can," said an unsmiling Hogan, "but I won't tell you."

All my recent conversations with living participants from both sides invariably came back to Hogan and how he did his job with dictatorial decisiveness. They find the stories fun in hindsight. Alliss says, "Hogan was serious as ever. Doug Sanders and I were friendly, and we played a few practice holes together. Hogan tore into him afterward. 'What in hell are you doing?' he said to Doug. Fraternizing with the opposition you know."

Sanders says: "He was a great champion and great motivator, and I was proud to play for him and my country. He'd stop you that week, take a puff of his cigarette, stare into your eyes and say, 'You will win today won't you?' He'd put pressure on you, and we responded. He didn't care if you carried only a driver and putter, as long as you won. He lived his life for one thing—to win."

Win was all Hogan did during a Ryder Cup career that saw him play on two teams and serve as captain three times (as playing captain in 1947 before that practice was discontinued in 1965 with the appointment of Byron Nelson). He established a 10:30 p.m. curfew in Houston as well as other rules reminiscent of a college coach on a road trip with a young team.

Working with superior talent and experience, as well as useful familiarity with a Champions course that was then a regular stop on the PGA Tour, he presumably had little to worry about. But he took no chances and was correct in pointing out afterward that the final score was misleading in its failure to show that more individual match outcomes were close than not.

As Hogan further said sportingly, a putt here or there would have made a significant difference. But the huge Bermuda greens at Champions befuddled the British all week as they left putts woefully short. And mediocre iron play didn't help.

The three-day format at the time called for a first day of morning and afternoon foursomes, followed by a day of morning and afternoon four-balls and a third day of morning and afternoon singles, with most of the afternoon pairings changed but not all. Each team consisted of 10 players, two sitting out each round. There were no captain's picks, the players all qualifying through a points system, for the American side at any rate.

Palmer and Gardner Dickinson led the romp, going undefeated in five matches each. They paired for two foursomes wins, were split up for the four-balls, then took turns beating young Jacklin in the two rounds of singles. If there was tension between Hogan and Palmer, whose pairing with Dickinson was broken up for good after the flyover, it didn't affect the Americans' momentum.

Jackie Burke Jr. was running the Champions club with Jimmy Demaret then, and has run it by himself since Demaret's death in '83. He says, "There were the incidents over the plane flyover and which ball to play, and I think Arnold resented that Hogan always just called him 'fella' which is kinda obscure." As usual, one story reminded Burke, one of the game's leading raconteurs, of others featuring Hogan and Palmer and also Billy Casper, the all-time U.S. Ryder Cup points leader with 23½ (the same total the American side ran up in 1967).

"At a tournament Ben would go to another course to practice," Burke says. "A young pro told me one time he wanted to go practice with him. I said, 'The very second you win 60 tournaments we'll see him about that.' "

Palmer and Julius Boros were 3 down at the turn of their four-ball match against Hugh Boyle and George Will, when the team score was still in some doubt. Burke, knowing Palmer's ber-competitive nature, told him on the way to the 10th tee that he'd heard about his famous charges and wondered if he would see one, a deliberate note of skepticism in his voice. If Palmer could take the match to the final hole, Burke said, he'd build him a watch. Palmer heard the bugler's call. He told Burke to follow him on the second nine—which he and Boros scorched to win 1 up. Coming off the 18th green, Palmer asked Burke where his watch was.

Burke, knowing Palmer needed another watch like he needed another fan in his gallery, pondered what he could give him that was unique, and eventually figured out that Palmer's two names add up to 12 letters that could correspond to the numbers on a clock. So he presented Palmer with a clock whose face reads "A-R-N-O-L-D-P-A-L-M-E-R." It hangs proudly in Palmer's home office.

If the '67 Cup was no contest on paper, it was sufficiently tense at the time, says Burke, whose own Cup record was 7-1. "It's never been jolly golf," he says. "It's a whole different level of pressure. Billy Casper, one of the great players of all time and great under pressure, was getting ready to go off in the first match, after the national anthems had been played and the flags raised, and he looked scared to death. His face was white. He came over to me, almost stuttering, and asked me what he should do. I told him to get up there and hit that squiggly little slice of his right down the middle. He did."

Casper was 4-0-1 that week. It turns out all these years later that Hogan began playing his wily tactical hand early in the week, when he asked PGA official Joe Black, a fellow Texan, to conduct a seminar on match-play rules for his players. "He said they didn't know them," Black says today. "It was smart of him. I told them in a meeting that in international competition they had a choice of the 1.62 British ball or the 1.68 American ball. Hogan immediately said they'd use the 1.62 ball. I don't think the players had thought about it until then. Bobby Nichols said he wouldn't play that ball. Hogan said, 'Then you won't play.' He wanted to give the opponents no advantage."

The small ball was better for distance on a long Champions course and for windy conditions that prevail in Texas. It did not lend itself to maneuvering and more sophisticated shotmaking.

Hogan might have been without much formal education, but he possessed a penetrating mind. Dickinson, his protégé, earned a degree in clinical psychology from LSU, did graduate work in psychology at Alabama and studied his hero closely. Dickinson once told me he determined, by slipping Hogan occasional test questions, that the man's IQ was genius level. Dickinson also believed Hogan's memory was photographic. Dickinson said he once put 20 random items on a table in front of Hogan, took them off—and Hogan identified them all.

On the subject of psychology there is the often-repeated tale of the gala opening dinner in Houston with the captains' introductions of their teams to a large civic attendance. Alliss remembers it with a rueful chuckle.

"Our captain, Dai Rees, went first … 'This chap was runner-up in the Swiss Open,' and so on and so on. Then Hogan had his men stand and gave that classic line: 'Ladies and gentlemen, the United States Ryder Cup team—the finest golfers in the world.' He sat down to huge applause. We were only 10 down at the start."

Johnny Pott vividly recalls team meetings with Hogan. "He was a hard man to address," says Pott. "He addressed you. At one meeting with us he said, 'Boys, let me tell you something. You don't have to be a rocket scientist to do this job. I'm going to pair straight hitters with straight hitters and crooked hitters with crooked hitters so you won't find yourselves in unfamiliar places.' Hell, Bobby Nichols and I were paired, and we'd learned to play out of the woods. We won every point."

In another meeting, Pott says, the subject was team attire. "He said, 'They've given us all these fancy clothes. I was never comfortable wearing someone else's clothes. Mr. Sanders, if you want to dress like a peacock, that's fine with me. I just don't want my name on that trophy as losing captain.' "

The Ryder Cup's competitive spirit carries on with Pott in the form of a biennial wager he makes with former British player Clive Clark, his neighbor in California. They watch the telecasts together, the loser paying for a gourmet dinner.

"I've been buying too long," Pott says.

He offers a theory for America's modern struggles against the expanded European side: "Back in '67 we didn't know the guys we were playing. The problem now is that our players are getting beat by their players regularly. Last time they had five of the top 10 money winners on our tour."

The Brits were keenly aware of Hogan. Jacklin remembers him going out on the course in his cart to watch his players in Houston. They didn't exactly find his presence soothing. "He would park and gaze at their swings, paying no attention to where the ball went," Jacklin says. "Gay Brewer would see him coming and almost poop in his pants. That was amusing."

Jacklin and his veteran partner, Dave Thomas, proved a formidable pair for the visitors in the foursomes, knocking off Brewer and Sanders, 4 and 3, in the morning round and Gene Littler and Al Geiberger, 3 and 2, in the afternoon.

"We jelled well," Jacklin says. "Dave was a terrible chipper. The par 3s at Champions are long with difficult carries, and all are even-numbered holes followed by par 5s, so he hit on the 3s, and I chipped if he missed the green. I chipped on the 5s, too. I was 23, just finding my sea legs. I had won a couple tour events in the U.K. that summer and just got my tour card over here in the States. I got thrown into the deep end to learn."

The Americans had looked uncomfortable in the unfamiliar foursome format early, but turned it on in the four-balls. Only Jacklin and Thomas scraped out a halve against Littler and Geiberger in the final match of the day, which the Brits claimed should have been stopped because of darkness. Thomas said he could not see the line on a short birdie putt at the end that would have won the match.

Finally, I will never, ever forget the week-ending Auld Lang Syne dinner given by the sponsoring PGA of America. We media types, the mere smattering of us, were invited to such functions in those days, before the event became so outsized that our access to captains and players was limited to mass interviews in the press center (there was no television with its vast crews in '67 either). That night we visited chummily with the newsmakers under circumstances that became increasingly relaxed as the libations flowed.

Even Hogan was somewhat at ease, if not effusive. I still have a large, handsome dinner program that was circulated and signed by the players and captains. Hogan's signature reflects the legend and his personality: It is taut and entirely legible, as if from an old-fashioned penmanship exam. I hear that such a program recently sold in Great Britain for $8,000. Mine is not for sale.

Excerpted from The Ryder Cup: Golf's Greatest Event by Martin Davis; published by The American Golfer, scheduled release: November 2008; $60.00; available at fine bookstores or direct from publisher, 203-862-9720; 250 pages.