News

Nothing Minor League About It

If all goes according to schedule, on July 13 a man will sign a raft of autographs after winning a tournament. Kids will thrust golf balls or T-shirt sleeves toward him, adults will offer programs and pairing sheets, tournament officials will set aside assorted mementos for charities and the host course.

When it seems his felt-tip marker is nearly dry, he will make the signature that means the most to him—on an ice cooler, the enormous white plastic kind found in a pickup truck's flatbed at a construction site. Although the beverage he fishes from the ice water will slake his thirst, signing the cooler's exterior will quench his soul.

This is how you know you've arrived on the Nationwide Tour: Win and sign Jaws, the perpetually stocked cooler on the tractor-trailer that hauls the circuit's leader boards and radios from stop to stop. This year's cooler, Jaws 8, bears signatures of some guys you barely know exist, names in scoreboard agate at the back of this magazine. But there is an unrealized value to those signatures, as attested to by some of the men who signed, say, Jaws 3 in 2003: Joe Ogilvie, Ryan Palmer, Brett Wetterich, Vaughn Taylor, Bo Van Pelt, Zach Johnson.

That July 13 signature also will commemorate two milestones for the circuit itself. The 554th tournament in its existence, making its debut the summer before the tour's 20th season, is its version of the Players, christened the Nationwide Tour Players Cup. And finally—after four title sponsors, several thousand players through its fields and about 500,000 travel miles—the tour will pay a seven-figure purse.

"Getting to $1 million is a psychological threshold that makes an important impact," says Bill Calfee, the tour's president. "Everything just kind of fell into place. The tournament came to us and wanted to do something bigger, they had a financial plan to get them to where they needed to be, they had a good golf course, dates to support and good crowds."

That enthusiastic statement begs an observation: A majority of golfers and fans have little idea the Nationwide Tour has so many stars in alignment, especially next week at Pete Dye GC in Bridgeport, W.Va. Its challenge remains elevating itself from backwater to major tributary. And the way that occurs, some tour officials say openly, is for the Nationwide to become the sole avenue for gaining a PGA Tour card, superseding the romanticized hell of the annual Qualifying Tournament.

That heady designation would underscore vast changes in the lower strata of pro competition since a January 1989 announcement that the Ben Hogan Co. had signed a five-year, $19-million agreement with the PGA Tour for a separate circuit. For decades the PGA Tour conducted satellite events to augment the incomes of lesser players back before the top 125 money-exemption category arrived in 1983, when "rabbits" endured Monday qualifying to get into weekly fields. The tour even cobbled together an abbreviated Tournament Players Series in the 1980s but it withered, assuring the considerable gulf between the PGA Tour's standards and dozens of lesser circuits.

"I'm one of the people who, if I didn't get a [PGA] Tour card, I had to go overseas or play 36-hole [mini-tour] tournaments on carts where you played for your entry fee," says Scott Dunlap, who turned pro in 1985 and competed in the inaugural 1990 season. "This is so much better than what my options were."

The Ben Hogan Tour was a quantifiable arena for kids trying to reach the bigs, vets prepping for the Senior (now Champions) Tour and club pros. The 30 tournaments went 54 holes, all but one offering a $100,000 purse. It provided spit-and-polish for the top five players on its money list, who were handed PGA Tour cards for the next year. That lucrative carrot made it worthwhile to abandon a single-city mini-tour, scrape together enough cash or max out credit cards and follow a connect-the-dots schedule roaming the U.S. in a counter-clockwise loop. Those 1990 events stretched 13,098 miles from site to site, a throwback to the PGA Tour's formative years when players spent long stretches in autos.

"Those first years I drove my Honda Civic and gasoline was $1 a gallon, we were playing for $20,000 first place, we stayed in private housing and saved money," recalls Esteban Toledo, who played 114 of the tour's first 120 events. "Sometimes if we wanted food we had to go off the course because some of the courses didn't have a clubhouse."

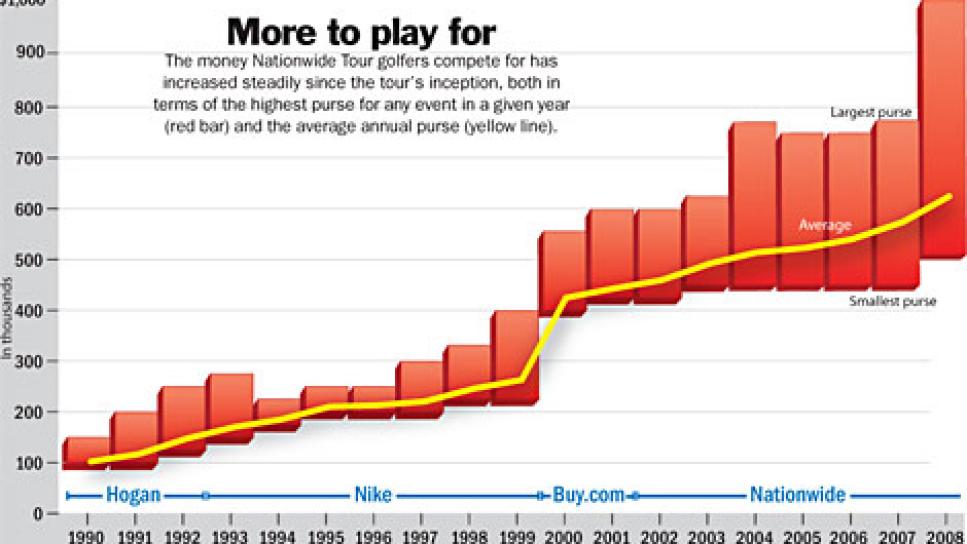

The Hogan Co. hit a financial wall after parent Cosmo World bought Pebble Beach for $840 million. Sponsorship passed in 1993 to Nike, then edging into golf. Under its aggressive watch, 72-hole formats were introduced and average purses inched past $250,000. By 2000, though, Nike stepped aside with Tiger Woods as its global billboard.

The circuit's third sponsorship ranks as one of the most abysmal in pro sports history. Computer and electronics seller Buy.com broke Compaq's record for sales by a first-year company with $111 million in 1998; the PGA Tour lassoed Buy.com as the Internet boomed. Purses nearly doubled overnight to a $425,000 average, but the dot-com bubble burst and in 2001, when the Jaws cooler tradition began, Buy.com bailed. Bricks-and-mortar insurer Nationwide, on the cusp of Fortune 100 status, signed a five-year deal in 2002.

Unlike the other sponsors, whose names fronted each title—the Ben Hogan Greater Greenville Classic, say, or Buy.com Omaha Classic—Nationwide bought in without naming rights. That freed tournaments to peddle their titles to companies with big local footprints—the BMW Charity Pro-Am at The Cliffs in Greenville, S.C., or Cox Classic in Omaha.

"We'd clearly not be playing for the purses we are," Calfee says of $19 million in prize money this season, six times the 1990 level. "We wouldn't have the impact we have back in the communities. And when you're talking about Bank of America as a title sponsor, BMW, Cox Communications, Xerox, that has an impact." It helps that the PGA Tour's 15-year deal with Golf Channel includes airtime for 16 tournaments—and 30- second commercial time as sponsor bait.

The Buy.com meltdown also prompted an assessment of the circuit by its PGA Tour parents, who have hardly altered the basic framework. It remains roughly 30 tournaments, many in pro golf-starved cities such as Boise, Idaho; Lafayette, La.; and Springfield, Mo.

But the guts of the thing, the players, have changed appreciably. In early years PGA Tour players, obsessed with their status, equated demotion to a Siberian gulag. In a classic chicken-and-egg equation, the more PGA Tour players competed on the Hogan and Nike, the more robust those competitions—and the stronger the abilities of those reaching the big tour. Stewart Cink, one of the first to become a household name, was Nike player of the year in 1996 with three wins. By 1997 he was hoisting the Greater Hartford Open title on the PGA Tour, a victory he duplicated last month at TPC River Highlands.

The Nationwide test is far different now. The season begins with four foreign events, requiring 17,000-plus air miles, or about 30 percent more miles than the 1990 players drove for the entire year. Now few weeks allow driving so players hopscotch on flights. Success does not come cheap; even misers encounter $70,000 in expenses while equipment, apparel and visor contracts pay a fraction of the big tour.

Reid Edstrom, who competed on several mini-tours for a decade before reaching the Nationwide Tour this season, realizes the finances pale compared to the PGA Tour. He won a spot in Monday qualifying for the ATT Classic outside of Atlanta, made the cut, "finished dead last and earned [almost] $10,500." An equivalent payout in a Nationwide-minimum purse of $500,000 is worth $1,200.

With every mark notched by grads on the PGA Tour, more cards were provided. It inaugurated an immediate "battlefield promotion" in 1997 for three-time winners in a season. And it gradually enriched the number of cards available via the money list, from five in 1990 to 25 last year. That matches the number offered to thousands of players in Q school, where everyone finishing from 26th on down in the final stage's 108 holes gets some kind of Nationwide status.

"Guys who are going to play well on [the Nationwide] won't have problems on the PGA Tour beyond maybe [being] out of their skin or starry-eyed," says Bryan DeCorso, a 37-year-old Canadian in his first full Nationwide season, whose checkered career has included stints caddieing on the PGA and Nationwide circuits and announcing on Golf Channel. "If you succeed here, you must know in your soul that you can succeed out there."

Now there are enough legitimate bodies to populate a duplicate Nationwide circuit. In addition to players demoted from the big tour—whose signatures lend a Jaws cooler immediate street cred—more than 60 pros from outside the U.S. have Nationwide cards. A fair number left the Challenge Tour, which has events in 24 nations across four continents, but awards just 10 cards to the PGA European Tour.

"I'm not going to go back to European Q school," announces Oskar Bergman, a Swede who played six Challenge seasons. "The guys over there are not happy with only having 10 cards." U.S. players are philosophical about the influx: "You go where the money is," says seventh-year Nationwide vet Jeff Klauk. "If all the money was in Australia, all the Americans would be down there. It's all about the Benjamins."

The PGA Tour anticipated this foreign wave a few years ago and began touting the Nationwide as the world's second-best tour. Nationwide players earn World Ranking points—five players are in the top 250, led by Greg Chalmers (157th) and Arjun Atwal (191st)—so the claim isn't entirely jingoistic. Despite the talent, the second-best moniker fell as flat as the original vision of golf's version of Triple A-class baseball, a flawed image heralded in that 1989 announcement that the circuit still can't shake.

Nationwide Tour officials, prepping for next year's 20th season, conducted market research on their circuit in 2007. In focus groups among even core golf fans, they say, knowledge of PGA Tour ownership of the circuit was hazy at best. The lower circuit's image improved, they say, when moderators began citing stats:

More than 220 PGA Tour victories and 11 majors, beginning with John Daly's win at the 1991 PGA Championship to Zach Johnson's Masters triumph in 2007.

Two-thirds of current PGA Tour members have played on the Nationwide and nearly as high a percentage of Nationwide members have PGA Tour experience.

Nationwide players who earn a PGA Tour card off the money list have, since 1991, kept those cards for a second season at a 41-percent clip, to 30 percent for Q school grads.

The research led to a slogan unveiled in January: PGA Tour Driven. The campaign plays up "The 25" money race by designating gold caddie bibs emblazoned with large numbers to the top players on each week's list. But, Calfee says, the stats also fueled far-reaching discussions in the upper echelons of the PGA Tour about the Nationwide Tour's slot in the pro continuum. Calfee hopes in a few years his tour will supplant the Q-school he endured five times as a journeyman in the 1980s. "If you believe that the mission of this tour is to determine the best players in the world who are not on the PGA Tour," he says, "they should come through the Nationwide Tour. All 50."

Calfee says all kinds of ideas are under consideration, from call-ups to the PGA Tour's Fall Finish for top earners to a lower standard for a battlefield promotion. Of course, rank-and-file PGA Tour members will scream bloody murder. Despite the circuit's longevity, Nationwide players do not uniformly receive pension contributions and other benefits that are de rigueur on the regular tour. There are no courtesy cars, few perks and the hordes of agents, teachers, journalists and sycophants tend to stay at the big tour's groaning buffet. If Nationwide players squeeze journeymen lacking World Golf Championship and invitational slots, or if those outside the top 125 don't have an immediate avenue back via Q school, such proposed changes could spark insurrection.

Those are battles for another day. For now, Nationwide officials will focus on next week's $1 million purse in West Virginia and an equivalent amount for the Nationwide Tour Championship in November. They will promote the heck out of "The 25" money race and root every week that a Nationwide product with his signature on a Jaws cooler wins a PGA Tour title. Because for them, that's the sip of recognition that quenches their souls.